Zabaniyah

In Islam the Zabaniyah (Arabic: الزبانية) (also spelled Zebani) are the tormentors of the sinners in hell. They appear namely in the Quran in verse 96:18. Identified with the Nineteen Angels of Hell in 66:6 and 74:30, they are further called "angels of punishment", the "Guardians of Hell",[1] "wardens of hell", and "angels of hell".[2] Some consider the zabaniya to be the hell's angels' subordinates.[3] As angels, the zabaniyah are, despite their gruesome appearance and actions, ultimately subordinative to God (Allah), and thus their punishment is considered just.[4]: 274

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

According to Quran and Hadith, the Zabaniyah angels are consisted of nineteen members.[5] Maalik are considered as the leader of nineteen Zabaniyah angels.[6][7][8]

While Christian Lange suggested the word Zabaniyah may have been derived from the syriac shabbāyā. Ephrem used this term for angels who conduct the souls after death.[9] According to Hasan al-Basri, they are God's minions on Judgment Day, driving the sinners into hell with "iron hooks".[10]

In Islamic traditions

The Zabaniyah angels were described as torturer of sinners in hell, where, according to Umar Sulaiman Al-Ashqar, were led by an angel named Maalik, who has once met by Muhammad, and archangel Gabriel, where they found Maalik always frowning and never smiled.[11] Al-Mubarrad suggested, zabāniya could derive from the idea of movement and the Zabaniyah are those who "push somebody [back]".[12] Quran exegete Qatada ibn Di'ama states that the term is used for policemen. Although it is true that the term is sometimes associated with earthly state's agents, this is a post-Quranic development,[13] similar to the view of Qurthubi which translate Zabaniyah as a police.[6] According to founder of PERSIS, Ahmad Hassan, in his exegesis work Tafsir al-Furqan, he interpret Zabaniyah etymologically as "mighty soldiers of Allah".[14]

Mujahid ibn Jabr defended the idea that zabaniya are angels against contrary assertions.[10]

Colby asserts description from traditional exegesis that God would have made them hardness into their hearts, for they may have no mercy towards the inmates.[15]

Physical description

According to Frederick S. Colby, who quoted some Isra Mi'raj tradition, Zabaniyah angels also the landscape of the first layer of hell and the fiery seas within, as The leader of the hell's angels, Malik, explains to Muhammad that the zabaniyya were created by God inside hell, so they have no desire to leave this place and feel comfortable in it.[15] However, the tradition from Diya al-Din al-Maqdisi narrated in his book, Shifah an-Nar, the quote of Hadith that Zabaniyah were created 1,000 year before hell created, and their strength increases everyday,[16] to the point that each of Zabaniyah angels could squeeze mankinds from each of their crowns to their ankles.[Notes 1]

Ibn al-Mundhir quoted Abu Bakr Ibn Mujāhid that the eyes of Zabaniyah were like lightning and their mouths were like Spurs of chicken [16] This also noted by Christian Lange from the classical exegesis works, that zabaniyah have "repulsive faces, eyes like flashing lightening, teeth white like cows horns, lips hanging down to their feet, and rotten breath".[18] Furthermore, According to the interpretation of Ibn Qutaybah in his work, Uyun al Akhbar, he quoted that Tawus ibn Kaysan has transmitted his description each of the Zabaniya's fingers equal to the number of the sinners that will be thrown into hell after the judgment day.[5] Another classical scholar, Abdullah ibn Ahmad, also narrated that the size of Zabaniyah were described that the distance between each of their shoulders were as long as the distance of 100 years of travels.[16] Meanwhile, both Ibn Rajab, [6] and Al-Qurtubi narrates in his exegesis on Surah 66:6 that the angels of hell were created from anger, and that tormenting creatures is to them like food for the children of Adam.[19] Al-Qurtubi also adds that Zabaniyah is an angels who perform their jobs by using bpth of their hands and feets to drag and torture sinners in hell.[20] Tabari narrated the distance between Zabaniyah shoulders are 500 years.[16] After the judgment day, One of Zabaniah were described as being able to drag entire sinners who are judged to enter hell while carrying a mountain on his shoulder, which he use to crush the sinners beneath them after they all entered hell.[16] For the similar case, Ibn Rajab also brought other narration which traced from Tabi'un Abu Imran al-Jawni.[6] Modern contemporary scholars also highlighting the Quran verse of At-Tahrim

"O you who have faith! Save yourselves and your families from a Fire whose fuel will be people and stones, over which are [assigned] severe and mighty angels, who do not disobey whatever Allah commands them and carry out what they are commanded."[Quran 66:6]

Muhammadiyah university highlighting here the words from those verses which describe the Zabaniyah, where Ghilaadhun (severe) were meant to be one of their characteristics of those angels does not have compassion and cruel towards those they tortured.[21] Meanwhile, another characteristic in these verse, Shiddad (mighty or solid) meant as those angels possessed strengths that so great to the point they cannot be defeated by anyone.[21] Tabari also stated narration from Ka'b that each of Zabaniyah angels armed with two-handled staff which could beat 700,000 peoples in each of its single swing.[16]

They are also described possessed wings, as according to the hadiths of Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, the Zabaniyah were appeared before Abu Jahl, as Muhammad prayed in the Kaaba, They scared Abu Jahl when he tried to trample on Muhammad's neck with his foot.[22] A similar narration, authorized by ibn Abbas, appears in Sahih Bukhari. Here, Muhammad explains Abu Jahl's retraction that Abu Jahl felt the presence of the zabaniyah.[23] In his Fath al-Bari, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani explores this event in greater detail, stating that Abu Jahl was asked about his retreat whereupon he answered that he suddenly saw winged terrifying monster in a trench filled with flames, between him and Muhammad.[24] Al-Baladhuri comments on this narration, that the angels which protected Muhammad were twelve zabaniyah as tall sky.[25]

Roles

Ibn Kathir explained that one of Zabaniyah conduct for the sinners which were thrown to hell are shackling each sinners arms to their neck before dragging them down.[17] Ibn Barrajan (d. 1141) giving commentary on Sura At-Tur that Moses and Aaron are protected by zabaniyah.[26]

Another Hadith narrates that an army of angels of punishment battled against the angels of mercy over the soul of a sinner.[27](p56) In some Turkish lore, it is believed that when both groups battle, their strikes cause thunder.[28] While the angels of mercy are said to be created from light (nur), the angels of punishment are usually said to be created from fire (nar).[29][30] However, this distinction is not universally accepted among Muslim scholars.[31] Ibn Kathir adding commentaries from natration of Hadith transmitted from Abd Allah ibn Mas'ud, that whoever wants to be save from Zabaniyah tortures (after judgment days), he should recite Basmala (frequently during his life), as the Basmala words are consisted of 19 letters, in accordance of the number of Zabaniyah angels.[32] [Notes 2] Muhammad al-Bukhari, in his commentary of his collection of Hadiths regarding afterlife, also added that Zabaniyah also inflict punishments towards peoples who commit Riba or usury by pelting their mouth with rocks while forcing them to swim in river of blood.[34] This hadith described the situation of peoples who commit usury in Barzakh, or a realm of afterlife, before the judgment day. Adam ibn Abd al-aziz describes the zabaniya as angels of death who, according to the Quran (4:97, 32:11), conduct the souls of sinners and question them in the grave.[35] Similar to the angelic pairs Nāzi'āt and Nāshiṭāt and Munkar and Nakir, they are assisting Azrael and seize the souls of the injust.[36] Ghazali states, they appear as black shadows to the dying person, pull their souls out of their bodies, and drag them to hell.[12]

Cultural interpretation

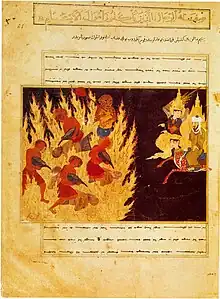

Islamic art commonly pictures them as horrifying demons with flames leaping from their mouth.[37] In Mi'raj literature, the zabaniyah are under command of the nineteen angels of punishment.[38] They guard the gates to hell, mentioned in the Quran. Throughout the Mi'raj literature, they are given different names including Suhâil, Tufail, Tarfail, Tuftuil, Samtail, Satfail, Sentatayil, Şemtayil, Tabtayil, Tamtail, Tantail, Sasayil, Tuhayil, Sutail, Bertail, Istahatail.[38] A zabani called Susāʾīl shows Muhammad the punishments of hell.[12]

As part of Isma'ili eschatology, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi identified the zabaniya with the seven planets, who administer the upper barzakhs, indicating that there is a kind of hell within the celestrial spheres. Accordingly, impure souls remain imprisoned within bodies, missing salvation in purely intellectual existence. The Houris appear as counterparts of the zabaniya, who are, in contrast to the zabaniya, items of knowledge from the beyond.[39]

Alternatively, it has been argued the term might have denoted a class of pre-Islamic demons.[40] Al-Khansa is said to have written a poet mentioning zabaniya. Similar to the jinn, they would ride on animals (eagles).[41] Another suggestion attributes the origin to rabbāniyya referring to the lords angelic council.[42] Since none of the older codices of the Quran (Mus'haf) contain variants of this term, it is unlikely it has been changed over time.[43] Another theory holds that this term may derive from Sumerian zi.ba.an.na ("The Scales") and Assyrian zibanitu (also referring to scales). However, Ibn Kathir has his commentary quoting Quran Al-Muddaththir,"Over it are nineteen [angels]. And We have not made the keepers of the Fire except angels. And We have not made their number except as a trial for those who disbelieve - that those who were given the Scripture will be convinced and those who have believed will increase in faith and those who were given the Scripture and the believers will not doubt and that those in whose hearts is hypocrisy and the disbelievers will say, "What does Allah intend by this as an example?" Thus does Allah leave astray whom He wills and guides whom He wills. And none knows the soldiers of your Lord except Him. And mention of the Fire is not but a reminder to humanity."[Quran 74:30–31 (Translated by si)] that the guardians of hells are only from angel race, none other.[17]

it has been argued the term might have denoted a class of pre-Islamic demons.[44] Al-Khansa is said to have written a poet mentioning zabaniya. Similar to the jinn, they would ride on animals (eagles).[41] Another suggestion attributes the origin to rabbāniyya referring to the lords angelic council.[45] Since none of the older codices of the Quran (Mus'haf) contain variants of this term, it is unlikely it has been changed over time.[46] Another theory holds that this term may derive from Sumerian zi.ba.an.na ("The Scales") and Assyrian zibanitu (also referring to scales). However, Ibn Kathir has his commentary quoting Quran Al-Muddaththir,"Over it are nineteen [angels]. And We have not made the keepers of the Fire except angels. And We have not made their number except as a trial for those who disbelieve - that those who were given the Scripture will be convinced and those who have believed will increase in faith and those who were given the Scripture and the believers will not doubt and that those in whose hearts is hypocrisy and the disbelievers will say, "What does Allah intend by this as an example?" Thus does Allah leave astray whom He wills and guides whom He wills. And none knows the soldiers of your Lord except Him. And mention of the Fire is not but a reminder to humanity."[Quran 74:30–31 (Translated by si)] that the guardians of hells are only from angel race, none other.[17] Hubert Grimme raised the possibility that zabaniya originally referred to a class of Arabian demons.[47] In favor of this theory is, that the poetress convert al-Khansa mentions zabaniya in one of her poems as supernatural creatures similar to Sa'aali (a type of jinn).[41] Further, al-Mubarrad associates zabaniya with demons. He states that afarit (a type of underworld demon) were sometimes called "ʿifriyya zibniyya".[12] Rudi Paret argues that the grammar of the term zabani indicates a characteristical action personified in a type of spirit. In that case, the zabani would refer to a spirit pushing someone back.[48]

As for the number nineteen, independent researcher Gürdal Aksoy suspects it refers to the sum of the seven planets and twelve signs of the zodiac,[49] as found in Mandaen literature, which, while suggestive, is ultimately inconclusive.[12][50] Scholars such as Richard Bell has found the evidence adduced for this apparent association to lack direct correspondence.[51] In a similar vein, Angelika Neuwirth sees the Qur'an's reference to nineteen as an "ostentatiously enigmatic element",[52] whereas Alan Jones suggests that "initially the meaning of 'nineteen' would have been vague."[53]

Similarities with other religion

The idea of punishing angels appears in earlier Abrahamic literature. In the Hebrew Bible, God sents punishing angels to smite enemies (for example, Exodus 12:23).[54] According to the Apocalypse of Paul, an angel casts the sinners into hell. In hell, such angels inflict pain on the inmates with iron hooks.[55] The Book of Enoch mentions punishing angels called satans who act as God's executioners on both sinful humans and fallen angels.[56] The Apocalypse of Peter also mentions angels torturing the sinners in a place of punishment.[57]

References

Footnotes

- This narration were transmitted from Hasan al-Basri, to his son, Yazid, until the end of transmission ended on Diya al-Din al-Maqdisi.[17]

- This correspondent was mentioned by al-Rutbi in al-Jami’ li Ahkam al-Qur’an (1/92) and Ibn Katheer in his “Tafsir” (1/18). The narration considered weak by Al-Dhahabi as he quoted in Sulaiman al-Aʽmash biography of Mizan al-I’tidal. But Al-Suyuti attributed it in “Al-Durr Al-Manthoor” (1/26) to Waki’, and Imam Waki’ bin Al-Jarrah has a famous interpretation. See: “The National Assembly” by Al-Hafiz Ibn Hajar (p. 113), which he deems the chain of narrators is authentic.[33]

Secondary sources

- Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti's Al-Haba'ik Fi Akhbar Al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN 978-1-136-50474-7 page 277

- translation from Quran.com

- Mohammed Rustom The Triumph of Mercy: Philosophy and Scripture in Mulla Sadra SUNY Press 2012 ISBN 9781438443416 p. 90

- Lange, Christian (2016). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-50637-3.

- Al-Suyuti (2021). Muhammad as Said Basyuni, Abu Hajir; Yasir, Muhammad (eds.). Misteri Alam Malaikat (Religion / Islam / General) (in Indonesian). Translated by Mishabul Munir. Pustaka al-Kautsar. pp. 29–33, 172. ISBN 9789795929512. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

Quoting Ibnul Mubarak from a book of az-Zuhd; ad Durr al-Manshur, chain narration from Ibnul Mubarak to Ibn SHihab (1/92)

- Lukman Hakiem; Sultan Mufit; Muhammad Miftahudin. Faisal Baasir politik jalan terus; Dahsyatnya Neraka Jahannam (in Indonesian). Yayasan Dharmapena Nusantara. pp. 219–220. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- Thomas Patrick Hughes (2009). A Dictionary of Islam Being a Cyclopædia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs, Together with the Technical and Theological Terms, of the Muhammadan Religion. :W.H. Allen / Oxford University. p. 15. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- James R Lewis; Evelyn Dorothy Oliver (2008). Angels A to Z (ebook). Visible Ink Press. p. 233. ISBN 9781578592579. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Lange, C. (2016). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Vereinigtes Königreich: Cambridge University Press.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 75

- Umar Sulaiman Al-Ashqar (1995). al-'Alam al Malaikah al-Abrar (Paperback) (in Arabic). Jordan: Dar an Nfs. Retrieved 24 October 2023.Video on YouTube

- Lange, Christian (2016). "Revisiting Hell's Angels in the Quran". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 74–100. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_005. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 78

- Hassan, Ahmad (2010). I.M, Thoyib (ed.). Al-Furqan : tafsir Qur'an (in Indonesian). Indonesian national Library; Al-Azhar Indonesian university. ISBN 978-602-95064-02. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Frederick S. Colby (2007). Narrating Muḥammad's Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn ʿAbbās Ascension Discourse. State University of New York Press. p. 207. ISBN 9780791477885. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Imam Jalaluddin Abdurrahman As-Suyuthi (2021). Misteri Alam Malaikat (ebook) (in Indonesian). Al-Kautsar. p. 72–74. ISBN 9789795929512. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

53 dalam kitab 'Uyun Al-Akhbar melansir dari Thawus bahwa Allah menciptakan Malik, dan menciptakan untuknya jari-jari sejumlah penghuni neraka.

- Ibn Kathir (November 2016). Hikmatiar, Ikhlas (ed.). Dahsyatnya Hari Kiamat Rujukan Lengkap Hari Kiamat dan Tanda-Tandanya Berdasarkan Al-Qur'an dan As-Sunnah (Paperback) (in Indonesian). Qisthi Press. p. 445. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- Lange, Christian (2016). "Introducing Hell in Islamic Studies". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 1–28. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_002. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.7.

- https://www.altafsir.com/Tafasir.asptMadhNo=1&tTafsirNo=5&tSoraNo=66&tAyahNo=6&tDisplay=yes&Page=2&Size=1&LanguageId=1

- Ammi Nur Baits (2015). "Siapa Malaikat Zabaniyah?". konsultasi syariah (in Indonesian). Yufid. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

Malaikat Zabaniyah dinamakan demikian, karena mereka mengerjakan tugas dengan kaki mereka, sebagaimana mereka mengerjakannya dengan tangan mereka.

- Doli Witro (2019). "Islamic Religious Education in the Family to Strengthen National Resilience of Surah At-Tahrim Verse 6 Perspective". 4 (2): 309. ISSN 2549-0427. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - al-Baghawi (2005). الأنوار في شمائل النبي المختار [Lights in the merits of the chosen Prophet (PBUH)] (Hadith, Religion / Islam / General) (in Arabic). دار الكتب العلمية، منشورات محمد علي البيضون،. p. 19. ISBN 9782745147349. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

Yes. He said: By Lat and `Uzza. If I were to see him do that, I would trample his neck, or I would smear his face with dust. He came to Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) as he was engaged in prayer and thought of trampling his neck (and the people say) that he came near him but turned upon his heels and tried to repulse something with his hands. It was said to him: What is the matter with you? He said: There is between me and him a ditch of fire and terror and wings. Thereupon Allah's Messenger (may peace he upon him) said: If he were to come near me the angels would have torn him to pieces. Then Allah, the Exalted and Glorious, revealed this verse- (the narrator) said: We do not know whether it is the hadith transmitted by Abu Huraira or something conveyed to him from another source: "Nay, man is surely inordinate, because he looks upon himself as self-sufficient. Surely to thy Lord is the return. Hast thou seen him who forbids a servant when he prays? Seest thou if he is on the right way, or enjoins observance of piety? Seest thou if he [Abu Jahl] denies and turns away? Knowest he not that Allah sees? Nay, if he desists not, We will seize him by the forelock-a lying, sinful forelock. Then let him summon his council. We will summon the guards of the Hell. Nay! Obey not thou him" (lcvi, 6-19). (Rather prostrate thyself.) Ubaidullah made this addition: It was after this that (prostration) was enjoined upon and Ibn Abd al-Ala made this addition that by "Nadiyah" he meant his people.

- Abd al-Rahman ibn Abdullah ibn Ahmad ibn Abi al-Hasan al-Khathami al-Suhaili (1967). bin Mansour bin Sayed Al-Shura, Majdi (ed.). الروض الأنف في شرح السيرة النبوية لابن هشام [Ar-Ruud al-Unf in Explanation of the Biography of the Prophet by Ibn Hisham - Volume] (Islam -- History, Islamic Empire -- History -- 622-661) (in Arabic). يطلب من دار الكتب الحديثة (Yathlib min Dar al Kitab wa al Hadith). p. 155. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Abd al-Majid al-Sheikh Abd al-Bari (2006). "3". الروايات التفسيرية في فتح الباري [Explanatory narratives of Fath al-Bari] (ebook) (Hadith study, Islam) (in Arabic). p. 81. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Muhammad Al-Saeed bin Bassiouni Zaghloul (2004). "10". موسوعة أطراف الحديث النبوي الشريف 1-11 ج10 [Encyclopedia of the parties to the Prophet's Hadith 1-11 c 10] (Religion / Islam / General) (in Arabic). Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah. p. 20. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Gallorini, Louise (2021). Orfali, Bilal (ed.). "The Symbolic Function of Angels in the Qur'ān and Sufi Literature". Students Publications (Theses, Dissertations, Projects). AUB ScholarWorks: 190. hdl:10938/22446.

Ibn Barrajān 2, 690.

- Awn, Peter J. (1983). "Mythic Biography". Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology. BRILL. pp. 18–56. doi:10.1163/9789004378636_003. ISBN 978-90-04-06906-0.

- Hans Wilhelm Haussig, Egidius Schmalzriedt Wörterbuch der Mythologie Klett-Cotta 1965 ISBN 978-3-129-09870-7 page 314 (german)

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN 9789004147645 p. 118

- Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM Brill 1995 page 94

- "Zebani nedir, zebaniler kimdir, ne demek, görevleri, cehennem".

- Ash-Shafuri (18 February 2021). Nasihat Langit Penenteram Jiwa_Buku 1: Memurnikan Akidah Dan (ebook) (in Indonesian). ebook. p. 103. ISBN 9786237163176.

... Barangsiapa yang ingin diselamatkan dari Zabaniyah yang berjumlah 19 itu , bacalah bismillahirrahmanirrahim , niscaya Allah akan ...

- Muhammad Salih Al-Munajjid. "Hadith on the virtue of Basmala and that it saves from the nineteen Zabaniyah". islamqa.info. Muhammad Al-Munajid. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- Muhammad Musthafa Imarah (2002) [1994]. Gasim Anuz, Fariq (ed.). Jawahir Al-Bukhari 800 Hadits Pilihan dan Penjelasannya (ebook) (in Indonesian). East Jakarta: Dar al Fikr; Pustaka Al-Kautsar. p. 358–359. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 74

- Zaki, Mona M. (2015). Jahannam in Medieval Islamic Thought (Thesis).

- Sheila Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800 Yale University Press 1995 ISBN 978-0-300-06465-0 page 62

- Ürkmez, Ertan. "Türk-İslâm mitolojisi bağlamında Mi ‘râç motifi ve Türkiye kültür tarihine yansımaları." (2015).

- Hoover, Jon (2016). "Withholding Judgment on Islamic Universalism". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 208–237. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_011. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.16.

- Tesei, Tommaso (2016). "The barzakh and the Intermediate State of the Dead in the Quran". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 29–55. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_003. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.8.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 80

- O'Meara, Simon (2016). "From Space to Place: The Quranic Infernalization of the Jinn". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 56–73. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_004. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.9.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 77

- Tesei, Tommaso (2016). "The barzakh and the Intermediate State of the Dead in the Quran". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 29–55. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_003. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.8.

- O'Meara, Simon (2016). "From Space to Place: The Quranic Infernalization of the Jinn". Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions. Brill. pp. 56–73. doi:10.1163/9789004301368_004. ISBN 978-90-04-30136-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.9.

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 77

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 79

- Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 82

- Aksoy, Gürdal. "Mezopotamyalı Tanrı Nergal'den Zerdüşti Kutsiyetlere Münker ile Nekir'in Garip Maceraları (On the Astrological Background and the Cultural Origins of An Islamic Belief: The Strange Adventures of Munkar and Nakir from the Mesopotamian god Nergal to the Zoroastrian Divinities) (2017)".

- Trompf, G. W.; Mikkelsen, Gunner B.; Johnston, Jay (eds.). The gnostic world. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-56160-8. OCLC 1056109897.

- Richard, Bell (1991). Bosworth, Clifford Edmund.; Richardson, M. E. J. (eds.). A commentary on the Qur'ān. University of Manchester. p. 453. ISBN 0-9516124-1-7. OCLC 24725147.

- Neuwirth, Angelika (2011). Der Koran: Band 1: Frühmekkanische Suren: Poetische Prophetie: Handkommentar mit Übersetzung. p. 369.

- Jones, Alan (2007). The Qurʼān. Cambridge. p. 545. ISBN 978-1-909724-32-7. OCLC 878413496.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lange, Christian. Locating hell in Islamic traditions. Brill, 2015. p. 93

- Lange, C. (2016). Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions. Vereinigtes Königreich: Cambridge University Press. p. 63

- Caldwell, William (1913). "The Doctrine of Satan: II. Satan in Extra-Biblical Apocalyptical Literature". The Biblical World. 41 (2): 98–102. doi:10.1086/474708. JSTOR 3142425. S2CID 144698491.

- Gregory, Andrew F.; Tuckett, Christopher Mark; Nicklas, Tobias (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Apocrypha. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964411-7.