Walther von der Vogelweide

Walther von der Vogelweide (c. 1170 – c. 1230) was a Minnesänger who composed and performed love-songs and political songs ("Sprüche") in Middle High German. Walther has been described as the greatest German lyrical poet before Goethe;[1] his hundred or so love-songs are widely regarded as the pinnacle of Minnesang, the medieval German love lyric, and his innovations breathed new life into the tradition of courtly love. He was also the first political poet to write in German, with a considerable body of encomium, satire, invective, and moralising.

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

Little is known about Walther's life. He was a travelling singer who performed for patrons at various princely courts in the states of the Holy Roman Empire. He is particularly associated with the Babenberg court in Vienna. Later in life he was given a small fief by the future Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II.

His work was widely celebrated in his time and in succeeding generations—for the Meistersingers he was a songwriter to emulate—and this is reflected in the exceptional preservation of his work in 32 manuscripts from all parts of the High German area. The largest single collection is found in the Codex Manesse, which includes around 90% of his known songs. However, most Minnesang manuscripts preserve only the texts, and only a handful of Walther's melodies survive.

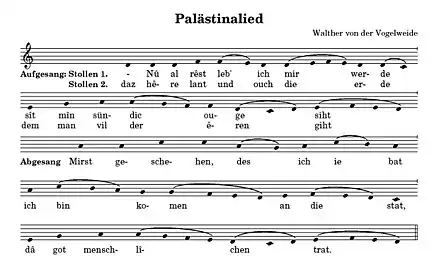

Notable songs include the love-song "Under der linden", the contemplative "Elegy", and the religious Palästinalied, for which the melody has survived.

Life history

For all his fame, Walther's name is not found in contemporary records, with the exception of a solitary mention in the travelling accounts of Bishop Wolfger of Erla of the Passau diocese: "Walthero cantori de Vogelweide pro pellicio v solidos longos" ('To Walther the singer of the Vogelweide five shillings for a fur coat.') The main sources of information about him are his own poems and occasional references by contemporary Minnesingers.[2] He was a knight, but probably not a wealthy or landed one. His surname, von der Vogelweide, suggests that he had no grant of land, since die Vogelweide ('the bird-pasture') seems to refer to a general geographic feature, not a specific place. He probably was knighted for military bravery and was a retainer in a wealthy, noble household before beginning his travels.

Birthplace

| Life[3] | |

|---|---|

| c. 1170 | Birth |

| c. 1190 | Start of professional life |

| Until 1198 | For Duke Frederick I of Austria |

| 1198 | Leaves Vienna court |

| 1198-1201 | For King Philip of Swabia |

| 1200 | At Leopold VI's investiture in Vienna? |

| 1201 | For Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia |

| 1203 | At the wedding of Leopold in Vienna? |

| 1204/05 | In Thuringia |

| 1212 | At the Hoftag of Emperor Otto IV in Frankfurt |

| 1212/13 (or until 1216?) | For Otto IV |

| 1212/13 | For Margrave Dietrich of Meißen |

| From late 1213 (1214?, 1216?) |

For King Frederick II (from 1220 Emperor) |

| From 1213/14 until April 1217 at the latest | For Hermann of Thuringia |

| 1215/16? | At the court of Duke Bernard II of Carinthia |

| 1216/17 | Vienna |

| 1219 | Vienna |

| 1220 | At the Hoftag of Frederick II in Frankfurt |

| 1220 | Receives fief from Frederick II |

| After 1220 | At the court of count Diether II of Katzenellenbogen |

| from 1220 (1224?) until 1225 |

For the Imperial Vicar Archbishop Engelbert of Cologne |

| 1224 (or 1225?) | At the Hoftag in Nürnberg |

| c. 1230 | Death |

Walther's birthplace remains unknown, and given the lack of documentary evidence, it will probably never be known exactly. There is little chance of deriving it from his name; in his day there were many so-called Vogelweiden in the vicinity of castles and towns, where hawks were caught for hawking or songbirds for people's homes. For this reason, it must be assumed that the singer did not obtain his name primarily for superregional communication, because it could not be used for an unambiguous assignment. Other persons of the high nobility and poets who traveled with their masters used the unambiguous name of their ownership or their place of origin; therefore, the name was meaningful only in the near vicinity, where only one Vogelweide existed or it was understood as a metaphoric surname of the singer. Pen-names were usual for poets of the 12th and 13th century, whereas Minnesingers in principle were known by their noble family name which was used to sign documents.

In 1974, Helmut Hörner identified a farmhouse mentioned in 1556 as "Vogelweidhof" in the urbarium of the domain Rappottenstein. At this time it belonged to the Amt Traunstein, now within the municipality Schönbach in the Lower Austrian Waldviertel. Its existence had already been mentioned without comment in 1911 by Alois Plesser, who also did not know its precise location. Hörner proved that the still-existing farmhouse Weid is indeed the mentioned Vogelweidhof and collected arguments for Walther being born in the Waldviertel ("Forest Quarter"). He published this in his 1974 book 800 Jahre Traunstein (800 years Traunstein), pointing out that Walther says "Ze ôsterriche lernt ich singen unde sagen" ("In Austria [at this time only Lower Austria and Vienna], I learned to sing and to speak"). A tradition says that Walther, one of the ten Old Masters, was a Landherr (land owner) from Bohemia, which does not contradict his possible origin in the Waldviertel, because in mediaeval times the Waldviertel was from time to time denoted as versus Boemiam. Powerful support for this theory was given in 1977[4] and 1981[5] by Bernd Thum (University Karlsruhe, Germany), which makes an origin in the Waldviertel very plausible. Thum began with an analysis of the content of Walther's work, especially of his crusade appeal, also known as "old age elegy", and concluded that Walther's birthplace was far away from all travelling routes of this time and within a region where land was still cleared. This is because the singer pours out his sorrows "Bereitet ist daz velt, verhouwen ist der walt" and suggests he no longer knows his people and land, applicable to the Waldviertel.

Additionally in 1987, Walter Klomfar and the librarian Charlotte Ziegler came to the conclusion that Walther might have been born in the Waldviertel. The starting point for their study is also the above-mentioned words of Walther. These were placed into doubt by research, but strictly speaking do not mention his birthplace. Klomfar points to a historical map which was drawn by monks of the Zwettl monastery in the 17th century, on the occasion of a legal dispute. This map shows a village Walthers and a field marked "Vogelwaidt" (near Allentsteig) and a related house belonging to the village. The village became deserted, but a well marked on the map could be excavated and reconstructed to prove the accuracy of the map. Klomfar was also able to partly reconstruct land ownership in this region and prove the existence of the (not rare) Christian name Walther.

Contrary to this theory, Franz Pfeiffer assumed that the singer was born in the Wipptal in South Tyrol, where, not far from the small town of Sterzing on the Eisack, a wood—called the Vorder- and Hintervogelweide—exists. This would, however, contradict the fact that Walther was not able to visit his homeland for many decades. At this time Tyrol was the home of several well-known Minnesingers. The court of Vienna, under Duke Frederick I of the house of Babenberg, had become a centre of poetry and art.[2]

Reinmar the Old

Here it was that the young poet learned his craft under the renowned master Reinmar the Old, whose death he afterwards lamented in two of his most beautiful lyrics; and in the open-handed duke, he found his first patron. This happy period of his life, during which he produced the most charming and spontaneous of his love-lyrics, came to an end with the death of Duke Frederick in 1198. Henceforward Walther was a wanderer from court to court, singing for his lodging and his bread, and ever hoping that some patron would arise to save him from this "juggler's life" (gougel-fuore) and the shame of ever playing the guest. He had few if any possessions and depended on others for his food and lodging. His criticism of men and manners was scathing; and even when this did not touch his princely patrons, their underlings often took measures to rid themselves of so uncomfortable a censor.[2]

Politics

Thus he was forced to leave the court of the generous duke Bernhard of Carinthia (1202–1256); after an experience of the tumultuous household of the landgrave of Thuringia, he warns those who have weak ears to give it a wide berth. After three years spent at the court of Dietrich I of Meissen (reigned 1195–1221), he complains that he had received for his services neither money nor praise.[2]

Generosity could be mentioned by Walther von der Vogelweide. He received a diamond from the high noble Diether III von Katzenelnbogen around 1214:[6]

Ich bin dem Bogenaere (Katzenelnbogener) holt – gar ane gabe und ane solt: – … Den diemant den edelen stein – gap mir der schoensten ritter ein[7]

Walther was, in fact, a man of strong views; and it is this which gives him his main significance in history, as compared to his place in literature. From the moment when the death of the emperor Henry VI (1197) opened the fateful struggle between empire and papacy, Walther threw himself ardently into the fray on the side of German independence and unity. Although his religious poems sufficiently prove the sincerity of his Catholicism, he remained to the end of his days opposed to the extreme claims of the popes, whom he attacks with a bitterness which can be justified only by the strength of his patriotic feelings. His political poems begin with an appeal to Germany, written in 1198 at Vienna, against the disruptive ambitions of the princes: "Crown Philip with the Kaiser's crown And bid them vex thy peace no more."[2]

He was present in 1198 at Philip's coronation at Mainz, and supported him till his victory was assured. After Philip's murder in 1208, he "said and sang" in support of Otto of Brunswick against the papal candidate Frederick of Hohenstaufen; and only when Otto's usefulness to Germany had been shattered by the Battle of Bouvines (1214) did he turn to the rising star of Frederick, now the sole representative of German majesty against pope and princes.[2]

From the new emperor, Walther's genius and zeal for the empire finally received recognition: a small fief in Franconia was bestowed upon him, which—though he complained that its value was little—gave him the home and the fixed position he had so long desired. That Frederick gave him a further sign of favour by making him the tutor of his son Henry (VII), King of the Romans, is more than doubtful. The fact, in itself highly improbable, rests upon the evidence of only a single poem, the meaning of which can also be interpreted otherwise. Walther's restless spirit did not suffer him to remain long on his new property.[2]

Later years

In 1217 he was once more at Vienna, and again in 1219 after the return of Duke Leopold VI from the crusade. About 1224 he seems to have settled on his fief near Würzburg. He was active in urging the German princes to take part in the crusade of 1228, and may have accompanied the crusading army at least as far as his native Tirol. In a poem he pictures in words the changes that had taken place in the scenes of his childhood, changes which made his life there seem to have been only a dream. He died about 1230, and was buried at Würzburg, after leaving instructions — according to the story — that the birds were to be fed at his tomb daily. His original gravestone with its Latin inscription has disappeared; but in 1843 a new monument was erected over the spot, called the Lusamgärtchen ("Little Lusam Garden"), today sheltered by the two major churches of the city.[8]

The Manuscripts

Walther's work is exceptionally well preserved compared to that of his contemporaries, with over 30 complete manuscripts and fragments containing widely varying numbers of strophes under his name. The most extensive collections of his songs are in four of the main Minnesang manuscripts:[9]

- MS A (the Kleine Heidelberger Liederhandschrift) has 151 strophes under Walther's name, along with others almost certainly written by Walther but included in the works of other Minnesänger (Hartmann von Aue, Liutold von Seven, Niune, Reinmar von Hagenau and Ulrich von Singenberg).[10]

- MS B (the Weingarten Manuscript) has 112 strophes under Walther's name.[11]

- MS C (the Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift, the Manesse Codex) has by far the largest collection, with 440 strophes and the Leich, and additional strophes by Walther under the names of other poets (Hartmann von Aue, Heinrich von Morungen, Reinmar von Hagenau, Rudolf von Neuenburg, Rudolf von Rotenburg, Rubin and Walther von Mezze).[12]

- MS E (the Würzburg Manuscript) has 212 strophes under Walther's name and some wrongly ascribed to Reinmar.

Manuscripts B and C have miniatures showing Walther in the pose described in the Reichston (L 8,4 C 2), "Ich saz ûf einem steine" ("I sat upon a stone").

In addition to these, there are many manuscripts with smaller amounts of material, sometimes as little as a single strophe.[13] In the surviving complete manuscripts, there are often missing pages in the sections devoted to Walther, which indicates lost material, as well blank space left by the scribes to make allowance for later additions.[9]

With the exception of MS M (the Carmina Burana), which may even have been compiled in Walther's lifetime, all the sources date from at least two generations after his death, and most are from the 14th or 15th centuries.[9][14]

Melodies

As with most Minnesänger of his era, few of Walther's melodies have survived. Certain or potential melodies to Walther's songs come from three sources: those documented in the 14th-century Münster Fragment (MS Z) under Walther's name,[15] melodies of the Meistersinger attributed to Walther, and, more speculatively, French and Provençal melodies of the trouvères and troubadours which fit Walther's songs and might therefore be the source of contrafactures. The latter are the only potential melodies to Walther's love songs, the remainder being for religious and political songs.

Münster Fragment

- The complete melody of the Palästinalied, "Nû alrêst lebe ich mir werde" (L14, 38; C 7)

- Partial melodies for

There are further melodies in two early manuscripts, M (the Carmina Burana) and N (Kremsmünster Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 127) but they are recorded in staffless neumes and cannot be reliably interpreted.[14][15]

Meistersang manuscripts

- The Meistersingers' Hof- oder Wendelweise is Walther's Wiener Hofton, "Waz wunders in der werlde vert!" (L20,16; C 10)

- The Meistersingers' Feiner Ton is Walther's Ottenton, "Herre bâbest, ich mac wol genesen" (L11,6; C 4) [16][18]

The ascription of other melodies to Walther in the Meistersang manuscripts (the Goldene Weise, the Kreuzton, and the Langer Ton) is regarded as erroneous.[16]

Possible contrafactures

The following songs by Walther share a strophic form with a French or Provençal song, and Walther's texts may therefore have been written for the Romance melodies, though there can be no certainty of the contrafacture:[18]

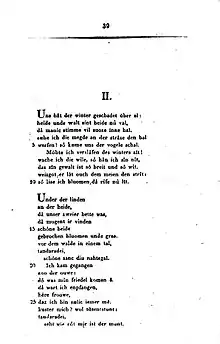

- "Uns hât der winter geschadet über al" (L39,1;C 15): "Quant voi les prés fuourir et blanchoir" by Moniot de Paris

- "Under der linden" (L39,11;C 16): the anonymous "En mai au douz tens novels"

- "Muget ir schouwen waz dem meien" (L51,13; C 28): "Quant je voi l'erbe menue" by Gautier d'Espinal

- "Diu welt was gelf, rôt unde blâ" (L75,25; C 52): "Amours et bone volonté" by Gautier d'Espinal

- "Frô Welt, ir sult dem wirte sagen" (L100,24; C 70) "Onques mais nus hons de chanta" by Blondel de Nesle

- "Wol mich der stunde, daz ich sie erkande" (L110,33; C 78): "Qan vei la flor" by Bernart de Ventadorn.

Lost manuscripts with melodies

There is evidence that the surviving volume of the Jenaer Liederhandschrift was originally accompanied by another with melodies for Walther's Leich and some Sprüche.[19] Further manuscript fragments containing melodies in the possession of Bernhard Joseph Docen (hence the "Docen fragments") were inspected by von der Hagen early in the 19th century, but are now lost.[9]

Legacy

Assessment

A contemporary assessment of Walther's songs comes from Gottfried von Strassburg, who, unlike modern commentators, was able to evaluate Walther's achievements as composer and performer, and who, writing in the first decade of the 13th century, proposed him as the "leader" of the Minnesänger after the death of Reinmar.

diu von der vogelweide. |

the Nightingale of Vogelweide! |

| —Tristan, ll.4801–11 | —Trans. A.T.Hatto[20] |

Grove Music Online evaluates Walther's work as follows:

He is regarded as one of the most outstanding and innovative authors of his generation... His poetic oeuvre is the most varied of his time,... and his poetry treats a number of subjects, adopting frequently contradictory positions. In his work he freed Minnesang from the traditional patterns of motifs and restricting social function and transformed it into genuinely experienced and yet universally valid love-poetry.[21]

Will Hasty's evaluation of the love songs is that:

Walther's main contribution to the German love lyric was to increase the range of roles that could be adopted by the singer and his beloved, and to lend the depiction of the experience of love new immediacy and vibrancy.[22]

Of the political works, Hasty concludes that:

In Walther's political and didactic poetry we again observe a consummately versatile poetic voice, one which finds new ways to give artistic expression to experience despite the constraints of the taste of audiences and patrons and by the authority of literary conventions.[23]

Reception

Walther is one of the traditional competitors in the tale of the song contest at the Wartburg. He appears in medieval accounts and continues to be mentioned in more modern versions of the story such as that in Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser. He is also named by Walther von Stolzing, the hero of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, as his poetic model.[24]

Walter is mentioned in Samuel Beckett's short story "The Calmative": "Seeing a stone seat by the kerb I sat down and crossed my legs, like Walther."[25]

In 1975, the German poet Peter Rühmkorf published Walther von der Vogelweide, Klopstock und ich, in which he provided modernised and colloquial verse translations of 34 songs by Walther, accompanied by commentary.[26][27]

Historical fiction with Walther in a major role includes Eberhard Hilscher's 1976 work Der Morgenstern, oder die vier Verwandlungen eines Mannes genannt Walther von der Vogelweide ("The Morning-Star, or the Four Metamorphoses of a man called Walther von der Vogelweide"), and two novels about Frederick II, Waltraud Lewin's Federico (1984) and Horst Stern's Mann aus Apulien (1986).[28]

In 2013, the Galleria Lia Rumma in Naples exhibited a series of works by Anselm Kiefer (two large paintings and a group of books) relating to "Under der linden" under the title "Walther von der Vogelweide für Lia".[29][30]

Commemoration

In 1889, a statue of Walther was unveiled in a square in Bolzano (see above), which was subsequently renamed the Walther von der Vogelweide-Platz. Under fascist rule, the statue was moved to a less prominent site, but it was restored to its original location in 1981.[24][31]

There are two statues of Walther in fountains in Würzburg, one near the Würzburg Residence and another in the Walther-Schule.[32] There are also statues in: Weißensee (Thuringia); Sankt Veit an der Glan and Innsbruck in Austria; and Duchcov in the Czech Republic.

- Statues

Statue at Weißensee, Thuringia

Statue at Weißensee, Thuringia The Franconia Fountain, Würzburg, Germany

The Franconia Fountain, Würzburg, Germany Fountain in the Walther-Schule, Würzburg

Fountain in the Walther-Schule, Würzburg

Fountain on main square in Sankt Veit an der Glan, Austria

Fountain on main square in Sankt Veit an der Glan, Austria Statue in Duchcov, Czech Republic

Statue in Duchcov, Czech Republic Statue in the Waltherpark, Innsbruck, Austria

Statue in the Waltherpark, Innsbruck, Austria

Apart from his grave in Würzburg, there are also memorials in: the Knüll-Storkenberg nature reserve, Halle (Westfalia); Herlheim (Franconia); the Walhalla memorial[33] near Regensburg; Lajen, South Tyrol,[34] Zwettl,[35] Gmunden and the ruined Mödling Castle, all in Austria.

- Memorials

Memorial in Halle, Westfalia

Memorial in Halle, Westfalia Memorial in Herlheim

Memorial in Herlheim.jpg.webp) Memorial of Walther's stay at Mödling Castle

Memorial of Walther's stay at Mödling Castle Memorial in Gmunden, Austria

Memorial in Gmunden, Austria

There are schools named after him in Bozen,[36] Aschbach-Markt[37] and Würzburg.[32]

Editions

There have been more scholarly editions of Walther's works than of any other medieval German poet's, a reflection of both his importance to literary history and the complex manuscript tradition.[38] The following highly selective list includes only the seminal 19th Century edition of Lachmann and the most important recent editions. A history of the main editions will be found in the introduction to the Lachmann/Cormeau/Bein edition.

Consistent reference to Walther's songs is made by means of "Lachmann numbers", which are formed of an "L" (for "Lachmann") followed by the page and line number in Lachmann's edition of 1827.[39] Thus "Under der linden", which starts on line 11 on page 39 of that edition (shown in the page image, right) is referred to as L39,11, and the second line of the first strophe is L39,12, etc.[40] All serious editions and translations of Walther's songs either give the Lachmann numbers alongside the text or provide a concordance of Lachmann numbers for the poems in the edition or translation.

- Lachmann, Karl, ed. (1827). Die Gedichte Walthers von der Vogelweide. Berlin: G. Reimer. The first scholarly edition and continually revised since 1827. However, the revised editions edited by Carl von Kraus between 1936 and 1959 are now considered out of keeping with modern editorial principles.[41] The most recent update, now the standard edition of Walther's works, is:

- Lachmann, Karl; Cormeau, Christoph; Bein, Thomas, eds. (2023). Walther von der Vogelweide. Leich, Lieder, Sangsprüche (16th ed.). De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110980608. ISBN 9783110980608.

- von der Hagen, Friedrich Heinrich, ed. (1838). Minnesinger. Deutsche Liederdichter des 12., 13., und 14. Jahrhunderts. Vol. 1. Leipzig: Barth. pp. 222–279. Retrieved 19 July 2017. Includes all Walther's songs known at the time.

- Paul, Hermann; Ranawake, Silvia, eds. (1997). Walther von der Vogelweide. Gedichte. Altdeutsche Textbibliothek 1. Vol. I Der Spruchdichter (11th ed.). Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 3-484-20110-X.

- Schweikle, Günther; Bauschke-Hartung, Ricarda, eds. (2009). Walther von der Vogelweide: Werke. Gesamtausgabe. Mittelhochdeutsch/Neuhochdeutsch. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek 819. Vol. 1: Spruchlyrik (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3150008195.

- Schweikle, Günther; Bauschke-Hartung, Ricarda, eds. (2011). Walther von der Vogelweide: Werke. Gesamtausgabe. Mittelhochdeutsch/Neuhochdeutsch. Reclams Universal-Bibliothek 820. Vol. 2: Liedlyrik (2nd ed.). Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3150008201.

Translations

Modern German

- Simrock, Karl (1833). Gedichte Walthers von der Vogelweide, übersetzt von Karl Simrock, und erläuterert von Wilhelm Wackernagel. Berlin. Verse translation.

- The 1894 edition

- The 1906 edition, lacking the commentary.

- Zooman, Richard (1907). Walther von der Vogelweide. Gedichte. Berlin: Wilhelm Borngräber. Translation only, but with Lachmann numbers.

- Spechtler, Franz Viktor (2003). Walther von der Vogelweide. Sämtliche Gedichte. Klagenfurt: Wieser. ISBN 978-3-85129-390-6.

- Kasten, Ingrid, ed. (2005). Deutsche Lyrik des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. Texte und Kommentare. Translated by Kuhn, Margherita (2nd ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag. ISBN 978-3-618-68006-2. Includes many of Walther's songs.

- Wapnewski, Peter (2008). Walther von der Vogelweide, Gedichte: Mittelhochdeutscher Text und Übertragung. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch. ISBN 978-3596900589.

- Brunner, Horst (2012). Walther von der Vogelweide, Gedichte: Auswahl. Mittelhochdeutsch/Neuhochdeutsch. Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3150108802.

- Schweikle's two-volume edition, listed above, includes parallel translation.

English

- Phillips, Walter Alison (1896). Selected poems of Walther von der Vogelweide the minnesinger. London: Smith, Elder. Translation only.

- Zeydel, Edwin H.; Morgan, Bayard Quincy (1952). Poems of Walther von der Vogelweide - Thirty New English Renderings in the Original Forms, with the Middle High German texts, Selected Modern German Translations. Ithaca, NY: Thrift.

- Richey, Margaret Fitzgerald (1967). Selected poems of Walther von der Vogelweide, edited with introduction, notes and vocabulary (4th ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 9780631018209.

- Goldin, Frederick (2003). Walther von der Vogelweide: The Single-Stanza Lyrics. Edited and Translated with Introduction and Commentary. Routledge Medieval Texts (Book 2). New York: Routledge. ISBN 041594337X. Parallel text; contains only the political songs.

Dictionary

- Meeßen, Dörte (2023). Walther von der Vogelweide Wörterbuch. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110776508. ISBN 978-3-11-077650-8.

See also

- Albrecht von Johansdorf

- Individual songs:

References

- Brunner 2012, p. back cover.

- Phillips 1911, p. 299.

- Scholz 2005, Chapter 4.

- Thum 1977, pp. 229f..

- Thum 1981.

- Stoess.

- Paul 1945, p. 102.

- Phillips 1911, pp. 299–300.

- Scholz 2005, Chapter 1.2.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XXVI.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XXVIII.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XXIX–XXX.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XXVI–XLV has a complete and up-to-date list (the most recent manuscript discovery dates from the 1980s).

- Hahn 1989, p. 668.

- Brunner 2013, p. L.

- Scholz 2005, Chapter 1.5.

- Brunner 2013, p. LI.

- Brunner 2013, p. LII.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XXXV.

- Hatto 1960, p. 107.

- Klaper.

- Hasty 2006, p. 113.

- Hasty 2006, p. 117.

- Brunner et al. 1996, pp. 235.

- Beckett 1946.

- Rühmkorf 1975.

- Wapnewski 1976.

- Brunner et al. 1996, pp. 249–50.

- Artsy 2013.

- Art in Progress 2013.

- Obermair 2015.

- WürzburgWiki.

- Purucker.

- Burgenverzeichnis Südtirols.

- Alamy.

- Gymnasium Walther von der Vogelweide Bozen.

- Volksschule Aschbach Markt.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. XCII.

- Klinck 2004, p. 163.

- Brunner et al. 1996, p. 39.

- Lachmann, Cormeau & Bein 2013, p. LXXXVI.

Sources

- Alamy. "Stock Photo - Zwettl: Memorial stone at the alleged birthplace of Walter von der Vogelweide". Alamy. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Art in Progress (20 November 2013). "Anselm Kiefer: Walther von der Vogelweide für Lia". Art in Progress. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Artsy (2013). "ANSELM KIEFER "Walther von der Vogelweide für Lia"". Artsy. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Beckett, Samuel (1946). "The Calmative". Stories and Texts for Nothing.

- Brunner, Horst (2013). "Die Melodien Walthers". In Lachmann, Karl; Cormeau, Christoph; Bein, Thomas (eds.). Walther von der Vogelweide. Leich, Lieder, Sangsprüche (15th ed.). De Gruyter. pp. XLVI–LIV. ISBN 978-3-11-017657-5.

- Brunner, Horst; Hahn, Gerhard; Müller, Ulrich; Spechtler, Franz Viktor (1996). Walther von der Vogelweide. Epoche — Werk — Wirkung. Munich: Beck. ISBN 3-406-39779-4.

- Burgenverzeichnis Südtirols. "Vogelweidhof in Lajen Ried". Burgenverzeichnis Südtirols. Archived from the original on 1 December 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Gymnasium Walther von der Vogelweide Bozen. "Home Page". Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Hahn G (1989). "Walther von der Vogelweide". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 10. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 666–697. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Hasty, Will (2006). "Walther von der Vogelweide". In Hasty, Will (ed.). German Literature of the High Middle Ages. Camden House History of German Literature, 3. Rochester, New York; Woodbridge Suffolk: Camden House. pp. 109–120. ISBN 1-57113-173-6.

- Hatto, A.T. (1960). Gottfried von Strassburg. Tristan. translated entire for the first time. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044098-4.

- Hörner, Helmut (2006). "Stammt Walther von der Vogelweide wirklich aus dem Waldviertel?". Das Waldviertel (in German). 55 (1): 13–21.

- Klaper, Michael. "Walther von der Vogelweide". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Klinck, Anne L. (2004). Anthology of Ancient Medieval Woman's Song. New York, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6310-X.

- Paul, Hermann, ed. (1945). Die Gedichte Walthers von der Vogelweide. Besorgt von Albert Leitzmann (in German) (6th ed.). Halle: Niemeyer Verlag. p. 102.

- Obermair, Hannes (2015). "Walthers Dichterexil vor 80 Jahren" (PDF). Das Exponat des Monats des Stadtarchivs Bozen. No. 46. Stadtarchiv Bozen (published October 2015). Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). "Walther von der Vogelweide". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 299–300.

- Purucker, Erwin. "Die Walhalla". panoptikum.net. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Rühmkorf, Peter (1975). Walther von der Vogelweide, Klopstock und ich. Reinbek: Rowohlt. ISBN 9783499250651.

- Scholz, Manfred Günter (2005). Walther von der Vogelweide. Sammlung Metzler, 316 (2nd ed.). Stuttgart: Metzler. ISBN 978-3-476-12316-9.

- Schumacher, Meinolf (2000). "Die Welt im Dialog mit dem 'alternden Sänger'? Walthers Absagelied 'Frô Welt, ir sult dem wirte sagen' (L. 100,24)". Wirkendes Wort (in German). 50: 169–188. PDF

- Stoess, Wolfgang. "Was von Katzenelnbogen übrig blieb [What remained of Katzenelnbogen]". Graf v. Katzenelnbogen (in German).

- Thum, Bernd (1977). "Die sogenannte 'Alterselegie' Walthers von der Vogelweide und die Krise des Landesausbaus im 13. Jahrhundert unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Donauraums". In Kaiser, Gert (ed.). Literatur - Publikum - Historischer Kontext. Beiträge zur älteren deutschen Literaturgeschichte (in German). Vol. 1. Bern. pp. 229 et seq. ISBN 978-3-261-02923-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thum, Bernd (1981). "Walther von der Vogelweide und das werdende Land Österreich". In Wolfram, Herwig; Brunner, Karl (eds.). Die Kuenringer. Das Werden des Landes Österreich. Stift Zwettl. 16. Mai - 26. Oktober 1981. Katalog des Niederösterreichischen Landesmuseums (in German). Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung. pp. 487–495.

- Volksschule Aschbach Markt. "Eine Chronik der Volksschule Aschbach Markt". Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Wapnewski, Peter (5 March 1976). "Zwischen Freund Hein und Heine". Die Zeit. Hamburg. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- WürzburgWiki. "Walther-Schule". Retrieved 27 August 2017.

Further reading

- Jones, George F. (1968). Walther von der Vogelweide. Twayne's World Authors, 46. New York: Twayne.

- Sayce, Olive (1981). Mediaeval German Lyric, 1150–1300: The Development of Its Themes and Forms in Their European Context. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0198157724.

External links

Bibliography

- Works by Walther von der Vogelweide at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walther von der Vogelweide at Internet Archive

- Works by Walther von der Vogelweide at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Literature by and about Walther von der Vogelweide in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Walther von der Vogelweide in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- Works by Walther von der Vogelweide at Projekt Gutenberg-DE (in German)

- Free University of Berlin: Annotated links at the Wayback Machine (archived January 1, 2016)

- "Walther von der Vogelweide". Repertorium "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages" (Geschichtsquellen des deutschen Mittelalters).

Manuscripts

- Handschriftencensus: Walther von der Vogelweide

- Kleine Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (A): Description — Digital facsimile (University Library, Heidelberg)

- Weingarten Manuscript (B): Description — Digital facsimile (Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart)

- Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (Manesse Codex)] (C): Description — Digital facsimile (University Library, Heidelberg)

- Würzburg Manuscript] (E): Description — Digital facsimile (University Library, Munich)

- Carmina Burana MS (M): Description — Digital facsimile (University Library, Munich)

- Kremsmünster, Stiftsbibl., Cod. 127 (N): Description

- Münster Fragment (Z): Description — Digital facsimile (University Library, Jena)

Texts

- Bibliotheca Augustana

- puella bella seven songs (within a study on female beauty in Minnesang)

- Poemhunter English verse translations of 16 songs

- Graeme Dunphy: English verse translations of two songs

- My Poetic Side: English verse translations of four songs

Music

- Discogs: Walther Von Der Vogelweide Discography

- The Salzburger Ensemble für Alte Musik: