Grand Casemates Gates

Grand Casemates Gates, formerly Waterport Gate, provide an entrance from the northwest to the old, fortified portion of the city of the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar, at Grand Casemates Square.

| Grand Casemates Gates | |

|---|---|

Casemates Gates | |

| Part of Fortifications of Gibraltar | |

| Grand Casemates Square, Gibraltar | |

Outside view of Grand Casemates Gates as seen from Market Place. | |

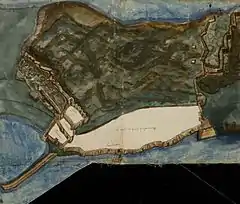

Fortifications of Gibraltar in 1597 (north is to the left in this map). The Old Mole, extending into the bay, is in the lower left. The enclosure above the base of the mole was the shipyard. The gate from the yard to the base of the mole is just visible. | |

Grand Casemates Gates | |

| Coordinates | 36.145248°N 5.353075°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Government of Gibraltar |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1727 |

| Materials | |

Background

The Rock of Gibraltar, linked to mainland Spain by a low isthmus, extends south into the Strait of Gibraltar which connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean. It is a strategic location that has been occupied in turn by the Moors, Spanish and British. The Rock is inaccessible on its eastern side, which rises in a tall and steep cliff. The town lies on the west side along the shore of the Bay of Gibraltar.[1] For many years a gate provided access from the sea into the northwest of the town through the defensive wall that ran along the shore of the bay.[2]

The Moors occupied Gibraltar for centuries until Ferdinand IV of Castile took Gibraltar in the 1309 siege.[3] In 1333 the Moors retook Gibraltar after a lengthy siege.[4] The Spanish regained Gibraltar in August 1462 during its eighth siege.[5] In 1704, during the War of the Spanish Succession, a combined Anglo-Dutch force captured the town of Gibraltar. In 1713 Spain ceded the Rock to the British "in perpetuity". Over the years that followed the British made extensive improvements to the defenses.[6]

Moorish and Spanish structures

The northern approaches to the town were defended by a Moorish Castle on the slopes of The Rock, from which walls ran down to the shore of the Bay of Gibraltar.[7] Around 1310 Ferdinand IV ordered the Giralda Tower to be built on the coast at the west end of the wall to protect the dockyard.[3] The Moors built a line wall, running south from the tower along the bay's western shore, which the Spanish later improved.[8] The Giralda Tower was converted into the North Bastion by the Italian engineer Giovan Giacomo Paleari Fratino in the 1560s.[9]

The esplanade just south of the tower is now Grand Casemates Square. It was a walled area where the Moors built their galleys. These were launched through a large arch in the line wall just north of today's Grand Casemates Gates, leading to the Waterport.[8] The Moorish Sea Gate (Spanish: Puerta del Mar) provided one of the three access gates to La Barcina, the shipbuilding area that is now Grand Casemates Square. The others were the Land Gate (Spanish: Puerta de Tierra now Landport Gate) and a southern gate, the Barcina Gate, through a wall that no longer exists.[2]

The Old Mole extending into the bay from a point just south of the tower provided shelter for trading vessels.[10] The mole provided an anchoring line for the galleys. An aqueduct ran from a well to the south along the line wall to the Waterport, where it replenished a reservoir from which water for the galleys was drawn.[11]

British developments

The British built the Line Wall Curtain in the 18th century running north–south along the shore of the bay.[12] It incorporates, and is to some extent built upon, older Spanish and Moorish fragments.[12] The Line Wall Curtain runs from the North Bastion south along the western coast of the town to Engineer Battery, just south of the New Mole. It protected the town from bombardment from ships in the bay and from troops landing from the sea.[13] The Moorish Sea Gate in the old line wall lay just north of today's Grand Casemates Gates, and was closed up.[8] The Waterport Gate, providing access to the town through the Line Wall from the shore south of North Bastion, was opened by the British in 1727.[14]

The Waterport Gate was the main entrance to Gibraltar in the early days of British occupation, described in 1748 as consisting

mainly of one street extending from Southport gate to Waterport Gate. Out of this long street run several shorter ones one of which, called the Irish-Street is of ill repute. The buildings of this town are generally mean and low, very few houses being above one story high. They are chiefly made of stone and the roof covered with Spanish tiles. The shops are small and ... are occupied by Genoese, Jews and Turks. Profane swearing and cursing is extremely common...[15]

In 1802 Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn was appointed Governor of Gibraltar. A disciplinarian, he forced constant drills and training, and was rigid about uniforms and was even concerned with beards and haircuts.[16] When he went as far as to order closure of the taverns in the town, an ill-planned mutiny broke out. The climax occurred at Waterport gate, where a gunner recalled that his captain ordered the artillery to "reverse [the] guns that were pointing to the Spanish lines, and point them on my comrade soldiers, who but a short time before had been fighting with me in Egypt." The mutineers scattered and were later rounded up and confined to their quarters.[17]

The Grand Casemates, a bombproof barracks, was started in the 1770s but was not finished until 1817.[18] In 1815 two gateways were opened in the wall at the Waterport, so that carriages could pass through in both directions at once.[19]

Ceremony of the Keys

During the Great Siege of Gibraltar, from 1779 to 1783, the Port Sergeant was responsible for locking the gates of the fortress at sunset. The Governor, General George Augustus Eliott, wore the keys of the gates at all other times, and the keys took on significance as a symbol of office.[20] The ceremony continued after the siege. An 1881 travel book described the keys being received from the governor twice daily and marched under escort to the gates, which were opened in the morning and closed each evening by a senior officer.[21] The ceremony is mentioned by Molly Bloom in James Joyce's novel Ulysses, referring to some time before 1888.[22] It is mentioned again in a 1908 description of Gibraltar.[23]

After the armistice that ended World War I the future United States Admiral Jerauld Wright was a lieutenant on a destroyer that showed the flag in the Mediterranean. In Gibraltar, he was struck by a squad of troops performing the ceremony, "...one had a limp and all were obviously Somme veterans. There were two fifers, one drummer, and one little fellow following with those gigantic keys... they swung past, boots pounding, heads in the air, fife and drum rolling..."[24] Vice-Admiral Kenneth Dewar was in Gibraltar in 1928. In his memoir The navy from within he wrote, "All the Spanish labourers employed on the breakwater had to return to Spanish territory by sunset. After the closing of the gates, a drum-and-fife band awoke the echoes in the narrow streets, accompanying a strong military guard which escorted the keys of the fortress to the Governor's Palace..."[25]

The practice was discontinued for a while, then revived as an annual Ceremony of the Keys by General Sir Charles Harington when he took office as governor in 1933.[27] The keys were ceremonially presented to his successor Governor Ironside every evening.[28] Today, a version of the ceremony is staged in Casemates Square at noon every Saturday by actors in uniforms similar to those worn by the defenders during the Great Siege.[29] The full military ceremony is held just twice a year.[30][31] In this ceremony, recalling the Great Siege, the gates of the fortress are symbolically locked. The Governor hands the keys to the Port Sergeant, who is accompanied by an armed escort, and he locks the gates.[27] The keys are then handed back to the governor.[32] Following tradition, drums and fifes accompany the Port Sergeant's party.[33]

In 2005 the Ceremony of the Keys was held on 19 May, and was attended by the governor and commander in chief, Sir Francis Richards.[34] The ceremony was again held in May during the term of office of his successor, Lieutenant General Sir Robert Fulton.[35] In October 2010 the escort was dressed in the uniform of the Black Watch, a highland regiment.[36] The Port Sergeant is ceremonial Custodian of the Keys.[37] In July 2012 a ceremony was staged in which the outgoing Port Sergeant handed the keys over to his successor.[38] On 6 September 2012 Governor Sir Adrian Johns inspected the parade of the Royal Gibraltar Regiment at the ceremony.[39] On this occasion, a group of young drummers performed in Casemates Square for ten minutes before the Parade.[40]

Gallery

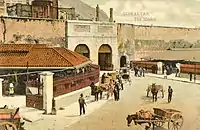

Old postcard of the Public Market outside Grand Casemates Gates as viewed from West Place of Arms.

Old postcard of the Public Market outside Grand Casemates Gates as viewed from West Place of Arms. Re-enactment of the Ceremony of the Keys at Grand Casemates Gates.

Re-enactment of the Ceremony of the Keys at Grand Casemates Gates. Waterport roundabout - gates visible in the background.

Waterport roundabout - gates visible in the background.

References

Citations

- Heriot 1792, p. 11ff.

- Fa & Finlayson 2006, p. 12.

- Harvey 1996, p. 37.

- Royal Engineers Journal 1910, p. 171.

- Fothergill Jackson 1987, p. 57-58.

- Fa & Finlayson 2006, p. 9-10.

- Gibraltar.

- James 1771, p. 403.

- Fa & Finlayson 2006, p. 19.

- Drinkwater 1786, p. 29.

- James 1771, p. 345.

- Ehlen & Harmon 2001, p. 110.

- Fa & Finlayson 2006, p. 8.

- Gibraltar - Main Sights.

- Poole 1748.

- Musteen 2005, p. 95-96.

- Musteen 2005, p. 97.

- Casemate Square.

- Musteen 2005, p. 227.

- Archer 2006, p. 154.

- Picturesque Europe 1881, p. 50.

- Raleigh 1977, p. 57.

- Howells 1908, p. 22.

- Key 2001, p. 44-45.

- Dewar 1939, p. 36.

- Cox 2012.

- Life goes calling ...

- Chartrand 2006, p. 91.

- June 20th 2009 - Today in Gibraltar.

- Fodor's 2011, p. 830.

- Chilton 2012, p. 180.

- Sep 06 - Ceremony.

- Ceremony of the Keys - Chronicle 2005.

- Gibraltar - The Ceremony of The Keys - eportbic.

- Gibraltar Ceremony of the Keys - Blipfoto.

- New Port Sergeant.

- Official Handover of the Keys.

- Ceremony of the Keys - Chronicle 2012.

- Ceremony of the Keys at new Grand Battery hall.

Sources

- Archer, Edward G. (2006). Gibraltar, Identity And Empire. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-34796-9. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "Casemate Square". Gibraltar Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Ceremony of the Keys". Gibraltar Chronicle. 19 May 2005. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Ceremony of the Keys". Gibraltar Chronicle. 6 September 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Ceremony of the Keys at new Grand Battery hall". GBC Broadcasting. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Chartrand, Rene (25 July 2006). Gibraltar 1779 - 1783. Osprey Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-84176-977-6. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Chilton, Glen (24 April 2012). The Attack of the Killer Rhododendrons: My Obsessive Quest to Seek Out Alien Species. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-1-4434-1147-9. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Cox, Jack (2012). "Travel Writers: Gibraltar Photo Journal". Pilot Community. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Dewar, Kenneth Gilbert Balmain (1939). The navy from within. V. Gollancz, ltd. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Drinkwater, John (1786). A history of the late siege of Gibraltar: With a description and account of that garrison, from the earliest periods. Printed by T. Spilsbury. p. 27. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Ehlen, Judy; Harmon, Russell S. (2001). The Environmental Legacy of Military Operations. Geological Society of America. ISBN 978-0-8137-4114-7. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Fa, Darren; Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603016-1.

- Fodor's (17 May 2011). Fodor's Spain 2011. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 830. ISBN 978-0-307-92853-5. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Fothergill Jackson, Sir William Godfrey (1987). The Rock of the Gibraltarians: a history of Gibraltar. Farleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3237-6. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Gibraltar". Fortified Places. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Gibraltar Ceremony of the Keys". Blipfoto. 30 October 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Gibraltar - Main Sights". Andalucia.com. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Gibraltar - The Ceremony of The Keys". eportbic. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Harvey, Maurice (1996). Gibraltar. Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-873376-57-7. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Heriot, John (1792). An historical sketch of Gibraltar, with an account of the siege which that fortress stood against the combined forces of France and Spain: including a minute and circumstantial detail of the sortie made by the garrison on the morning of Nov. 27, 1781 ... Printed by B. Millan for J. Edward. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Howells, William Dean (1908). Roman holidays, and others. Harper & brothers. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- James, Thomas (1771). The History of the Herculean Straits, Now Called the Straits of Gibraltar: Including Those Ports of Spain and Barbary that Lie Contiguous Thereto : in Two Volumes ; Illustrated with Copper Plates. Rivington. p. 344. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "June 20th 2009 - Today in Gibraltar". The-Rock-of-Gibraltar.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Key, David M. (May 2001). Admiral Jerauld Wright--warrior among diplomats. Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-89745-251-9. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "Life goes calling on Britain's General Ironside at Gibraltar". LIFE. Time Inc. 31 July 1939. p. 64. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Naval Review (London). 1941. p. 368. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "New Port Sergeant". GBC News. 30 July 2012. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Official Handover of the Keys". Gibraltar Chronicle. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Poole, Robert (1748). The beneficent bee: or, traveller's companion. Containing each day's observation, in a voyage from London, to Gibraltar, Barbadoes, ... 1996 Tito Benady. p. 392. ISBN 978-1170605622. Quoted in Chipolina, José. "A History of the Chipulina Family". Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- Musteen, Jason R. (5 April 2005). Becoming Nelson's Rock and Wellington's Refuge: The Ascendency of Gibraltar During the Age of Napoleon (1793-1815). Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations (Ph.D thesis). Florida State University. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Picturesque Europe. 5 vols. [in 6]. Cassell. 1881. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Raleigh, John Henry (1977). The Chronicle of Leopold and Molly Bloom: Ulysses As Narrative. University of California Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-520-03301-6. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Royal Engineers Journal. Institution of Royal Engineers. 1910. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Sep 06 - Ceremony of the Keys Re-enactment". Your Gibraltar TV. 6 September 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

External links

- "Ceremony Of The Keys At Gibraltar 1949 (video)". British Pathé.