Music of Wales

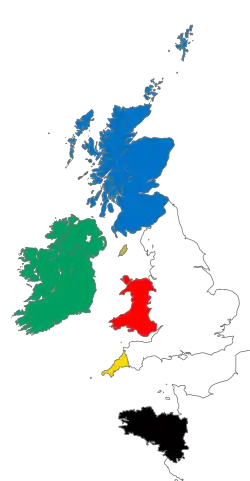

The Music of Wales (Welsh: Cerddoriaeth Cymru), particularly singing, is a significant part of Welsh national identity, and the country is traditionally referred to as "the land of song".[1]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| People |

| Art |

This is a modern stereotype based on 19th century conceptions of Nonconformist choral music and 20th century male voice choirs, Eisteddfodau and arena singing, such as sporting events, but Wales has a history of music that has been used as a primary form of communication.[1]

Historically, Wales has been associated with folk music, choral performance, religious music and brass bands. However modern Welsh music is a thriving scene of rock, Welsh language lyricism, modern folk, jazz, pop, and electronic music. Particularly noted in the UK are the Newport rock scene, once labelled 'the new Seattle', and the Cardiff music scene, for which the city has been labelled 'Music City', for having the second highest number of independent music venues in the UK.[2]

History

Early song

Wales has a history of folk music related to the Celtic music of countries such as Ireland and Scotland. It has distinctive instrumentation and song types, and is often heard at a twmpath (folk dance session), gŵyl werin (folk festival) or noson lawen (a traditional party similar to the Gaelic "Céilidh"). Modern Welsh folk musicians have sometimes reconstructed traditions which had been suppressed or forgotten, and have competed with imported and indigenous rock and pop trends.

Wales has a history of using music as a primary form of communication.[1] Harmony and part singing is synonymous with Welsh music. Examples of well-developed, vertical harmony can be found in the Robert ap Huw Manuscript dating back to the 1600s. This text contains pieces of Welsh music from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that show amazing harmonic development. [3][4] The oldest known traditional songs from Wales are those connected to seasonal customs such as the Mari Lwyd or Hunting the Wren, in which both ceremonies contain processional songs where repetition is a musical feature.[1] Other such ceremonial or feasting traditions connected with song are the New Year's Day Calennig and the welcoming of Spring Candlemas in which the traditional wassail was followed by dancing and feast songs. Children would sing 'pancake songs' on Shrove Tuesday and summer carols were connected to the festival of Calan Mai.[1]

For many years, Welsh folk music had been suppressed, due to the effects of the Act of Union, which promoted the English language,[5] and the rise of the Methodist church in the 18th and 19th century. The church frowned on traditional music and dance, though folk tunes were sometimes used in hymns. Since at least the 12th century, Welsh bards and musicians have participated in musical and poetic contests called eisteddfodau; this is the equivalent of the Scottish Mod and the Irish Fleadh Cheoil.[6]

18th and 19th century, religious music

Music in Wales is often connected with male voice choirs, such as the Morriston Orpheus Choir, Cardiff Arms Park Male Choir and Treorchy Male Voice Choir, and enjoys a worldwide reputation in this field. This tradition of choral singing has been expressed through sporting events, especially in the country's national sport of rugby, which in 1905 saw the first singing of a national anthem, Wales's Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, at the start of an international sporting encounter.

Welsh traditional music declined with the rise of Nonconformist religion in the 18th century, which emphasized choral singing over instruments, and religious over secular uses of music; traditional musical styles became associated with drunkenness and immorality. The development of hymn singing in Wales is closely tied with the Welsh Methodist revival of the late 18th century.[7] The hymns were popularised by writers such as William Williams, while others were set to popular secular tunes or adopted Welsh ballad tunes.[7] The appointment of Henry Mills as a musical overseer to the Welsh Methodist congregations in the 1780s saw a drive to improve singing throughout Wales. This saw the formation of local musical societies and in the first half of the 19th century Musical primers and collections of tunes were printed and distributed.[7] Congregational singing was given further impetus with the arrival of the temperance movement, which saw the Temperance Choral Union (formed in 1854) organising annual singing festivals, these included hymn singing by combined choirs. The publication of Llyfr Tonau Cynulleidfaol by John Roberts in 1859 provided congregations with a body of standard tunes that were less complex with unadorned harmonies. This collection began the practice of combining together to sing tunes from the book laid the foundation for the Cymanfa Ganu (the hymn singing festival).[8] Around the same period, the growing availability of music in the tonic sol-fa notation, promoted by the likes of Eleazar Roberts, allowed congregations to read music more fluently.[9] One particularly popular hymn of this period was "Llef".

In the 1860s, a revival of traditional Welsh music began, with the formation of the National Eisteddfod Society, followed by the foundation of London-area Welsh Societies and the publication of Nicholas Bennett's Alawon fy Ngwlad ("Tunes of my Land"), a compilation of traditional tunes, in the 1890s.[10]

19th–20th century, secular music

A tradition of brass bands dating from the Victorian era continues, particularly in the South Wales Valleys, with Welsh bands such as the Cory Band being one of the most successful in the world.

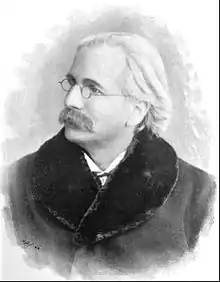

Although choral music in the 19th century by Welsh composers was mainly religious, there was a steady body of secular songs being produced. Composers such as Joseph Parry, whose work Myfanwy is still a favourite Welsh song, were followed by David Jenkins and D. Emlyn Evans, who tailored songs specifically for the Victorian music market.[9] These secular hymns were embraced by the emerging male voice choirs, which formed originally as the tenor and bass sections of chapel choirs, but also sang outside the church in a form of recreation and fellowship.[11] The industrial workforce attracted less of a jollity of English glee clubs and also avoided the more robust militaristic style of music. Composers such as Charles Gounod were imitated by Welsh contemporaries such as Parry, Protheroe and Price to cater for a Welsh fondness of dramatic narratives, wide dynamic contrasts and thrilling climaxes.[11] As well as the growth of male voice choirs during the industrial period, Wales also experienced an increase in the popularity of brass bands. The bands were popular among the working classes, and were adopted by paternalistic employers who saw brass bands as a constructive activity for their work forces.[12] Solo artists of note during the nineteenth century included charismatic singers Robert Rees (Eos Morlais) and Sarah Edith Wynne, who would tour outside Wales and helped build the country's reputation as a "land of song".[13][14]

In the twentieth century, Wales produced a large number of classical and operatic soloists of international reputation, including Ben Davies, Geraint Evans, Robert Tear, Bryn Terfel, Gwyneth Jones, Margaret Price, Rebecca Evans and Helen Watts, as well as composers such as Alun Hoddinott, William Mathias, Grace Williams and Karl Jenkins. From the 1980s onwards, crossover artists such as Katherine Jenkins, Charlotte Church and Aled Jones began to come to the fore. Welsh National Opera, established in 1946, and the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World competition, launched in 1983, attracted attention to Wales's growing reputation as a centre of excellence in the classical genre.

Composer and conductor Mansel Thomas OBE (1909–1986), who worked mainly in South Wales, was one of the most influential musicians of his generation. For many years employed by the BBC, he promoted the careers of many composers and performers. He himself wrote vocal, choral, instrumental, band and orchestral music, specialising in setting songs and poetry. Many of his orchestral and chamber music pieces are based on Welsh folk songs and dances.

Post-1945, popular music

After World War II, two significant musical organisations were founded, the Welsh National Opera and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, both were factors in Welsh composers moving away from choral compositions to instrumental and orchestral pieces. Modern Welsh composers such as Alun Hoddinott and William Mathias produced large scale orchestrations, though both have returned to religious themes within their work. Both men would also explore Welsh culture, with Mathias setting music to the works of Dylan Thomas, while Hoddinott, along with the likes of Mervyn Burtch and David Wynne, would be influenced by the poetic and mythical past of Wales.[9]

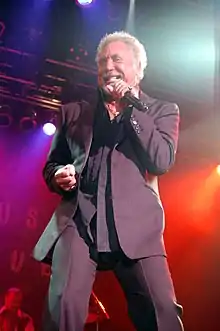

The 20th century saw many solo singers from Wales become not only national but international stars. Ivor Novello, who was a singer-songwriter during the First World War. Also, opera-singers such as Geraint Evans and later Delme Bryn-Jones found fame post World War II. The 1960s saw the rise of two distinctive Welsh acts, Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey, both of whom defined Welsh vocal styles for several generations.

.jpg.webp)

The 1960s saw important developments in both Welsh and English language music in Wales. The BBC had already produced Welsh language Radio programmes, such as Noson Lowen in the 1940s, and in the 1960s the corporation followed suite with television shows Hob y Deri Dando and Disc a Dawn giving Welsh acts a weekly stage to promote their sound. A more homely programme Gwlad y Gan was produced by rival channel TWW which set classic Welsh songs in idyllic settings and starred baritone Ivor Emmanuel. The Anglo-American cultural influence was a strong draw on young musicians, with Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey becoming world-famous singers; and the growth of The Beatles' Apple Records label saw Welsh acts Mary Hopkin and Badfinger join the roster. Not to be outdone, the short lived Y Blew, born out of Aberystwyth University, became the first Welsh language pop band in 1967.[16] This was followed in 1969 with the establishment of the Sain record label, one of the most important catalyst for change in the Welsh language music scene.[17]

In more modern times there has been a thriving musical scene. Bands and artists which have gained popularity include acts such as Man, Budgie, and solo artists John Cale & Mary Hopkin in the early 1970s and solo artists Bonnie Tyler and Shakin' Stevens in the 1980s, but through mimicking American music styles such as Motown or Rock and Roll. The Welsh language scene saw a dip in commercial popularity, but a rise in experimentation with acts such as punk band Trwynau Coch leading into a 'New Wave' of music. Bands that followed, like Anhrefn and Datblygu, found support from BBC Radio 1 disc jockey John Peel, one of the few DJs outside Wales to champion Welsh language music.

Wales embraced the new music of the 1980s and 1990s, particularly with the thriving Newport rock scene for which the city was labelled 'the new Seattle'. Acts and individuals based in the city during the period included Joe Strummer of The Clash, Feeder, The Darling Buds, Donna Matthews of Elastica, as well as Skindred and punk and metal acts. Famous performers or attendees at venues such as TJ's included Oasis, Kurt Cobain, and others.

21st century

The early 21st century produced a credible Welsh 'sound' embraced by the public and the media press of Great Britain. Such acts included the Manic Street Preachers, Stereophonics, Catatonia, Super Furry Animals and Gorky's Zygotic Mynci. The first two allowed the Welsh pop scene to flourish, and while not singing in Welsh they brought a sense of Welshness through iconography, lyrics and interviews. The latter two bands were notable for bringing Welsh language songs to a British audience. Music venues and acts thrived in the 2010s, with the noted success of the Cardiff music scene, for which the city has been labelled 'Music City'.

Styles of Welsh music

Traditional folk music

Early musical traditions during the 17th and 18th century saw the emergence of more complex carols, away from the repetitive ceremonial songs. These carols featured complex poetry based on cynghanedd, some were sung to English tunes, but many used Welsh melodies such as 'Ffarwel Ned Puw'.[1] The most common Welsh folk song is the love song, with lyrics pertaining to the sorrow of parting or in praise of the girl. A few employ sexual metaphor and mention the act of bundling. After love songs, the ballad was a very popular form of song, with its tales of manual labour, agriculture and the every day life. Popular themes in the 19th century included murder, emigration and colliery disasters; sung to popular melodies from Ireland or North America.[1]

The instrument most commonly associated with Wales is the harp, which is generally considered to be the country's national instrument.[18] Though it originated in Italy, the triple harp (telyn deires, "three-row harp") is held up as the traditional harp of Wales: it has three rows of strings, with every semitone separately represented, while modern concert harps use a pedal system to change key by stopping the relevant strings. After losing ground to the pedal harp in the 19th century, it has been re-popularised through the efforts of Nansi Richards, Llio Rhydderch and Robin Huw Bowen. The penillion is a traditional form of Welsh singing poetry, accompanied by the harp, in which the singer and harpist follow different melodies so the stressed syllables of the poem coincide with accented beats of the harp melody.[19]

The earliest written records of the Welsh harpists' repertoire are contained in the Robert ap Huw manuscript, which documents 30 ancient harp pieces that make up a fragment of the lost repertoire of the medieval Welsh bards. The music was composed between the 14th and 16th centuries, transmitted orally, then written down in a unique tablature and later copied in the early 17th century. This manuscript contains the earliest body of harp music from anywhere in Europe and is one of the key sources of early Welsh music.[20] The manuscript has been the source of a long-running effort to accurately decipher the music it encodes.

Another distinctive instrument is the crwth, also a stringed instrument of a type once widespread in northern Europe, it was played in Wales from the Middle Ages, which, superseded by the fiddle (Welsh Ffidil), lingered on later in Wales than elsewhere but died out by the nineteenth century at the latest.[21] The fiddle is an integral part of Welsh folk music. Other traditional instruments from Wales include the Welsh Bagpipes and Pibgorn.

Folk music

Welsh folk is known for a variety of instrumental and vocal styles, as well as more recent singer-songwriters drawing on folk traditions.

By the late 1970s, Wales, like its neighbours, had seen the beginning of a roots revival, the beginnings of which can be traced back to the 1960s folk singer-songwriter Dafydd Iwan. Iwan was instrumental in the creation of a modern Welsh folk scene, and is known for fiercely patriotic and nationalistic songs, as well as the foundation of the Sain record label. The Festival Interceltique de Lorient saw the formation of Ar Log, who spearheaded a revival of Welsh fiddling and harp-playing, and continued recording into the 21st century. A Welsh session band, following in the footsteps of their Irish counterparts Planxty, Cilmeri recorded two albums with a uniquely Welsh feel. Welsh folk rock includes a number of bands, such as Moniars, Gwerinos, The Bluehorses, Bob Delyn a'r Ebillion and Taran.

Sain was founded in 1969 by Dafydd Iwan and Huw Jones with the aid of funding from Brian Morgan Edwards.[22] Originally, the label signed Welsh singers, mostly with overtly political lyrics, eventually branching out into a myriad of different styles. These included country music (John ac Alun), singer-songwriters (Meic Stevens), stadium rock (The Alarm) and classical singers (Aled Jones, Bryn Terfel).

The folk revival picked up energy in the 1980s with Robin Huw Bowen and other musicians achieving great commercial and critical success. Later into the 1990s, a new wave of bands including Fernhill, Rag Foundation, Bob Delyn A'r Ebillion, Moniars, Carreg Lafar, Jac y Do, Boys From The Hill and Gwerinos found popularity. Jac y Do is one of several bands that now perform twmpathau all over the country for social gatherings and public events. Welsh traditional music was updated by punk-folk bands delivering traditional tunes at a much increased tempo; these included early Bob Delyn a'r Ebillion and Defaid. The 1990s also saw the creation of Fflach:tradd, a label which soon came to dominate the Welsh folk record industry with a series of compilations, as well as thematic projects like Ffidil, which featured 13 fiddlers. Some Welsh performers have mixed traditional influences, especially the language, into imported genres, Soliloquise for example and especially John ac Alun, a Welsh language country duo who are perhaps the best-known contemporary performers in Welsh.

In June 2007, Tŷ Siamas was opened in Dolgellau. Tŷ Siamas is the National Centre for Traditional Music, with regular sessions, concerts, lessons, an interactive exhibition and a recording studio.

Pop and rock

In the non-traditional arena, many Welsh musicians have been present in popular rock and pop, either as individuals, (e.g. Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, Bonnie Tyler, Dave Edmunds, Shakin' Stevens), individuals in groups (e.g. John Cale of The Velvet Underground, Green Gartside of Scritti Politti, Julian Cope of Teardrop Explodes and Andy Scott of Sweet, Roger Glover of Deep Purple and Rainbow), or as bands formed in Wales (e.g. Amen Corner, The Alarm, Man, Budgie, Badfinger, Tigertailz, Young Marble Giants), but not until the 1990s did Welsh bands begin to be seen as a particular grouping. Following on from an underground post-punk movement in the 1980s, led by bands like Datblygu and Fflaps, the 1990s saw a considerable flowering of Welsh rock groups (in both Welsh and English languages) such as Catatonia, Manic Street Preachers, Feeder, Stereophonics, Super Furry Animals, The Pooh Sticks, 60ft Dolls and Gorky's Zygotic Mynci.

The 21st century has seen the emergence of a number of new artists, including Marina and the Diamonds, Skindred, Lostprophets, The Kennedy Soundtrack, James Kennedy (musician), Kids in Glass Houses, Duffy, Christopher Rees, Bullet for My Valentine, The Automatic, Goldie Lookin Chain, People in Planes, Los Campesinos!, The Victorian English Gentlemens Club, Attack! Attack!, Gwenno, Kelly Lee Owens, Funeral for a Friend, Hondo Maclean, Fflur Dafydd, The Blackout, The Broken Vinyl Club, The Joy Formidable and The Anchoress. More abrasive alternative acts such as Jarcrew, Mclusky and Future of the Left – all well known within the independent music community and known as Welsh acts – have also received modest commercial success in the UK. Quite a strong neo-progressive/classic rock scene has developed from Swansea-based band Karnataka and other bands that have links to them. These include Magenta, The Reasoning and Panic Room.

Electronic music

Llwybr Llaethog has produced bilingual electronic music. DJ Sasha is from Hawarden, Flintshire. Also worth noting are the successful Drum and Bass DJ High Contrast who is from Cardiff, the veteran house outfit K-Klass from Wrexham, and the Swansea-based progressive breaks producers Hybrid. Escape into the Park and Bionic Events are examples of the Welsh Hard Dance scene. On 16 July 2011 Sian Evans of trip hop, synthpop Bristol based band Kosheen had a No.1 Official UK Singles Charts hit in collaboration with DJ Fresh.

Hip-hop

Welsh hip-hop and rap artists include Goldie Lookin Chain,[23] LEMFRECK[24] and Astroid Boys.[25] Bilingual artists include Mr Phormula[26] and more recently, Sage Todz,[27] Dom James and Lloyd.[28]

Welsh language popular music

There is a thriving Welsh-language contemporary music scene ranging from rock to hip-hop which routinely attracts large crowds and audiences, but they tend to be covered only by the Welsh-language media.

In 2013 the first Welsh Language Music Day was held, taking place each year in February. Events mark the use of Welsh language in a wide range of genres of music, and locations include Womanby Street in Cardiff as well as London, Swansea, Brooklyn and even Budapest.

Every year, Mentrau Iaith Cymru, The National Eisteddfod and BBC Radio Cymru have their national 'Battle of the Bands,' where young, upcoming Welsh bands can compete for £1000, and, what is thought to be one of the greatest possible achievements for a Welsh language act, to perform at Maes B, on its final night. In addition to Maes B, there are a number of various Welsh language music events throughout the year that have gained popularity in the past few years. In February each year the Welsh magazine 'Y Selar' hosts an award ceremony in Aberystwyth University where Welsh music fans from all over the country go to see the most popular and upcoming bands perform. There's also the 'Dawns Rhyngolegol' where the Welsh societies from every University in the UK gather to celebrate the best Welsh language music in Wales.

Current outlets

Welsh bands have the outlet for audiences, on such media as BBC Wales, BBC Cymru, S4C and The Pop Factory. In particular, BBC Radio 1's Bethan and Huw and BBC Radio Wales's Adam Walton support new Welsh music at their respective stations.

Notes

- Davies (2008), pg 579.

- "Cardiff to become 'Music City' to protect and grow venues". BBC News. 14 December 2017.

- Livezey, Bronwyn (2018). The Voices of Angels in the Land of Zion: The Welsh Chapter of the Tabernacle Choir.

- Crossley-Holland, Peter (1948). Music in Wales. Hinrichsen Edition Limited.

- Harper, Sally (2007). Music in Welsh Culture Before 1650: A Study of the Principal Sources. Ashgate. p. 298. ISBN 9780754652632.

- McCoy, Edain (2013). Celtic Myth & Magick: Harness the Power of the Gods & Goddesses. Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 25. ISBN 9781567186611.

- Davies (2008), pg 580.

- Davies (2008), pg 768.

- Davies (2008), pg 581.

- G. Grove, Grove's dictionary of music and musicians, col. 3 (St. Martin's Press., 6th edn., 1954), p. 410.

- Davies (2008), pg 532.

- Davies (2008), pg 79.

- Davies (2008) p.445

- Davies (2008) p.734

- "BBC.co.uk/Wales – Welsh number ones". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Popular music: Items from the 'Y Blew' archive". llgc.org.uk. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Davies (2008), pg 585.

- Davies (2008), pg 353.

- Davies (2008), pg 662.

- "Music of the Robert ap Huw Manuscript". Bangor University. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Davies (2008), pg 179.

- "Sain – The History". sainwales.com. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Bevan, Nathan (21 September 2019). "An oral history of Goldie Lookin' Chain". WalesOnline. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Latest acts revealed for the festival dubbed the 'Welsh Glastonbury'". Nation.Cymru. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Salter, Scott (17 January 2019). "The resurgence of Welsh rap". Ron Magazine. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Hughes, Brendan (20 October 2012). "Rapper Mr Phormula to make history with first Welsh rap at MOBO awards". WalesOnline. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- Jones, Branwen (14 March 2022). "Rapper shares incredible Welsh-language drill music clip". WalesOnline. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Watch: Welsh language rappers find their calling with new single 'Pwy Sy'n Galw?'". Nation.Cymru. 21 May 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

References

- Davies, John; Jenkins, Nigel (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- Mathieson, Kenny (2001). Mathieson, Kenny (ed.). Celtic music, Wales, Isle of Man and England. Backbeat Books. pp. 88–95. ISBN 0-87930-623-8.

- Broughton, Simon; Ellingham, Mark. "Harps, Bards and the Gwerin". In McConnachie, James; Duane, Orla (eds.). World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Penguin Books. pp. 313–319. ISBN 1-85828-636-0.

External links

- BBC Wales Music

- Tŷ Siamas, the National Centre for Traditional Music

- Tŷ Cerdd / Music Centre Wales – a collection of links to music-based organisations in Wales.

- Music pages on Wales.com website

- Folk Radio Cymru

- From Old Country to New World: Emigration in Welsh ballads — audio of lecture by Professor E. Wyn James, Cecil Sharp House, London (2015)