Politics of Wales

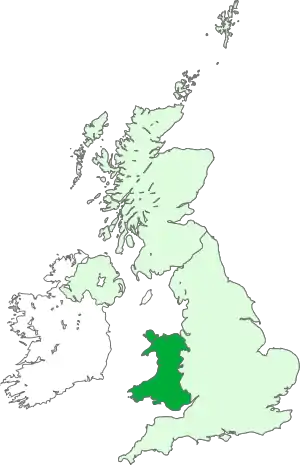

Politics in Wales forms a distinctive polity in the wider politics of the United Kingdom, with Wales as one of the four constituent countries of the United Kingdom (UK).

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

| Politics of Wales |

|---|

|

|

Constitutionally, the United Kingdom is a unitary state with one sovereign parliament delegating power to the devolved national parliaments, with some executive powers divided between governments. Under a system of devolution adopted in the late 1990s three of the four countries of the United Kingdom, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, voted for limited self-government, subject to the ability of the UK Parliament in Westminster, nominally at will, to amend, change, broaden or abolish the national governmental systems. As such, the Senedd (Welsh Parliament; Welsh: Senedd Cymru) is not de jure sovereign. Since then, further Welsh devolution has granted the Senedd additional powers.

Executive power in the United Kingdom is vested in the King-in-Council, while legislative power is vested in the King-in-Parliament (the Crown and the Parliament of the United Kingdom at Westminster in London). The Government of Wales Act 1998 established devolution in Wales, and certain executive and legislative powers have been constitutionally delegated to the Welsh Parliament. The scope of these powers was further widened by the Government of Wales Act 2006.

Overview

Since 1999 most areas of domestic policy have been decided within Wales via the Senedd and the Welsh Government.[1]

Judicially, Wales remains within the jurisdiction of England and Wales. In 2007, the National Assembly for Wales (renamed as the Senedd from May 2020) gained the power to enact Wales-specific Measures. Following the 2011 Welsh devolution referendum, the National Assembly was given the power to create Acts.

Wales, together with Cheshire, used to come under the jurisdiction of the Court of Great Session, and therefore was not within the English circuit court system. Yet it has not been its own distinct jurisdiction since the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, at which point Welsh Law was replaced by English Law.

Before 1998, there was no separate government in Wales. Executive authority rested in the hands of the HM Government, with substantial authority within the Welsh Office since 1965.[1] Legislative power rested within the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Judicial power has always been with the Courts of England and Wales, and the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (or its predecessor the Law Lords).

History

English rule

Wales was conquered by England in 1283. The 1284 Statute of Rhuddlan annexed the territory to England.[2] Owain Glyndwr briefly restored Welsh independence in a national uprising that began in 1400 after his supporters declared him Prince of Wales. He convened Wales' first Senedd in Machynlleth in 1404, but the rebellion was put down by 1412.[3]

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, passed by the English Parliament in the reign of Henry VIII, united the Principality and the Marches of Wales, creating a formalised border for the first time. Wales became part of the realm England.[4] The Welsh legal system of Hywel Dda that had existed alongside the English system since the conquest by Edward I, was now fully replaced. Penal laws enacted after the Welsh revolt were obosoleted by acts that made the Welsh people citizens of the realm, and all the legal rights and privileges of the English were extended to the Welsh for the first time.[5] These changes were widely welcomed by the Welsh people, although more controversial was the requirement that Welsh members elected to parliament must be able to speak English, and that English would be the language of the courts.[6]: 268–73

The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 stated that all laws applying to England would also be applicable to Wales, unless the body of the law explicitly stated otherwise. However, during the latter part of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century the notion of a distinctive Welsh polity gained credence. In 1881 the Welsh Sunday Closing Act was passed, the first such legislation exclusively concerned with Wales. The Central Welsh Board was established in 1896 to inspect the grammar schools set up under the Welsh Intermediate Education Act 1889, and a separate Welsh Department of the Board of Education was formed in 1907. The Agricultural Council for Wales was set up in 1912, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries had its own Welsh Office from 1919.[7]

Home rule movement

Despite the failure of popular political movements such as Cymru Fydd, a number of institutions, such as the National Eisteddfod (1861), the University of Wales (Prifysgol Cymru) (1893), the National Library of Wales (Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru) (1911) and the Welsh Guards (Gwarchodlu Cymreig) (1915) were created. The campaign for disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales, achieved by the passage of the Welsh Church Act 1914 (effective from 1920), was also significant in the development of Welsh political consciousness. Without a popular base, the issue of home rule did not feature as an issue in subsequent General Elections and was quickly eclipsed by the depression. By August 1925 unemployment in Wales rose to 28.5%, in contrast to the economic boom in the early 1920s, rendering constitutional debate an exotic subject.[8] In the same year Plaid Cymru was formed with the goal of securing a Welsh-speaking Wales.[9]

Following the Second World War the Labour Government of Clement Attlee established the Council for Wales and Monmouthshire, an unelected assembly of 27 with the brief of advising the UK government on matters of Welsh interest.[10] By that time, most UK government departments had set up their own offices in Wales.[7] By 1947, a unified Welsh Regional Council of Labour became responsible for all Wales.[11] In 1959 the Labour council title was changed from "Welsh Regional council" to "Welsh council", and the Labour body was renamed Labour Party Wales in 1975.[11]

The post of Minister of Welsh Affairs was first established in 1951, but was at first held by the UK Home Secretary. Further incremental changes also took place, including the establishment of a Digest of Welsh Statistics in 1954, and the designation of Cardiff (Caerdydd) as Wales's capital city in 1955. However, further reforms were catalysed partly as a result of the controversy surrounding the flooding of Capel Celyn in 1956. Despite almost unanimous Welsh political opposition the scheme had been approved, a fact that seemed to underline Plaid Cymru's argument that the Welsh national community was powerless.[12]

In 1964 the incoming Labour Government of Harold Wilson created the Welsh Office under a Secretary of State for Wales, with its powers augmented to include health, agriculture and education in 1968, 1969 and 1970 respectively. The creation of administrative devolution effectively defined the territorial governance of modern Wales.[13]

Labour's incremental embrace of a distinctive Welsh polity was arguably catalysed in 1966 when Plaid Cymru president Gwynfor Evans won the Carmarthen by-election (although in fact Labour had endorsed plans for an elected council for Wales weeks before the by-election). However, by 1967 Labour retreated from endorsing home rule mainly because of the open hostility expressed by other Welsh Labour MPs to anything "which could be interpreted as a concession to nationalism" and because of opposition by the Secretary of State for Scotland, who was responding to a growth of Scottish nationalism.[14]

In response to the emergence of Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party (SNP) Harold Wilson's Labour Government set up the Royal Commission on the Constitution (the Kilbrandon Commission) to investigate the UK's constitutional arrangements in 1969.[15] Its eventual recommendations formed the basis of the 1974 White Paper Democracy and Devolution: proposals for Scotland and Wales.,[15] which proposed the creation of a Welsh Assembly. However, voters rejected the proposals by a majority of four to one in a referendum held in 1979.[15][16]

The election of a Labour Government in 1997 brought devolution back to the political agenda. In July 1997, the government published a White Paper, A Voice for Wales, which outlined its proposals for devolution, and in September 1997 an elected Assembly with competence over the Welsh Office's powers was narrowly approved in a referendum. The National Assembly for Wales (Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru) was created in 1999, with further authority devolved in 2007, with the creation of a Welsh legal system to adjudicate on specific cases of Welsh law. Following devolution, the role of the Secretary of State for Wales greatly reduced. Most of the powers of the Welsh Office were handed over to the National Assembly; the Wales Office was established in 1999 to supersede the Welsh Office and support the Secretary of State.[7]

Devolved era

Between 1999 and 2007 there were three elections for the National Assembly. Labour won the largest share of votes and seats in each election and has always been in government in Wales, either as a minority administration or in coalition, first with the Liberal Democrats (2000 to 2003) and with Plaid Cymru between 2007 and 2011.[17] The predominance of coalitions is a result of the Additional Member System used for Assembly elections, which has worked to the benefit of Labour (it won a higher share of seats than votes in the 1999, 2003 and 2007 elections) but not given it the same advantage the party has enjoyed in first-past-the-post elections to Welsh seats in the House of Commons.[17]

Policy divergence between Wales and England has arisen largely because Welsh governments have not followed the market-based English public service reforms introduced during the premiership of Tony Blair. In 2002, First Minister Rhodri Morgan said that a key theme of the first four years of the Assembly was the creation of a new set of citizenship rights that are free at the point of use, universal and unconditional. He accepted the Blairite mantra of equality of opportunity and equality of access, but emphasised what he called "the fundamentally socialist aim of equality of outcome" - in stark contrast to the approach of Blair, who said that the true meaning of equality is specifically "not equality of outcome".[18]

Marking ten years of devolution in a 2009 speech, Morgan highlighted free prescriptions, primary school breakfasts and free swimming as 'Made in Wales' initiatives that had made "a real difference to people’s everyday lives" since the National Assembly came into being.[19] However, some authors have argued that the approach to public services in England has been more effective than that in Wales, with health and education "cost(ing) less and delivering more".[17] Unfavourable comparisons between National Health Service waiting lists in England and Wales were a contentious issue in the first and second Assemblies.[20]

Nevertheless, a 'progressive consensus' based on faith in the power of government, universal rather than means-tested services, co-operation rather than competition in public services, a rejection of individual choice as a guide to policy and a focus on equality of outcome continued to underpin the One Wales coalition government in the Third Assembly.[21] The commitment to universalism may be tested by increasing budgetary constraints; in April 2009 a senior Plaid Cymru adviser warned of impending health and education cuts.[22]

On 1 June 2020, the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020 came into force, giving 16- and 17-year-olds in Wales and legally resident foreign nationals the right to vote in Senedd (Welsh Parliament) elections.[23]

Political parties

Labour Party

Throughout much of the 19th century, Wales was a bastion of the Liberal Party. From the early 20th century, the Labour Party has emerged as the most popular political party in Wales. Before 2009 they had won the largest share of the vote in Wales at every UK General Election, National Assembly for Wales election and European Parliament election since 1922.[24] An all Wales unit was formed within the Labour Party for the first time in 1947.[25] The Wales Labour Party has traditionally been most successful in the industrial south Wales valleys, north east Wales and urban coastal areas, such as Cardiff, Newport and Swansea.

Conservative Party

The Welsh Conservative Party has historically been the second political party of Wales, having obtained the second largest share of the vote in Wales in a majority of UK general elections since 1885.[26] In three General Elections (1906, 1997 and 2001) no Conservative MPs were returned to Westminster, while on only two occasions in the 20th century (1979 and 1983) have more than a quarter of Welsh constituencies been represented by Conservatives. However, in the 2009 European Parliament elections the Conservatives polled higher than the Labour party in Wales.[27]

Plaid Cymru

Plaid Cymru is the principal Welsh nationalist political party in Wales. The Party was formed in 1925, but did not contest a majority of Welsh seats in any UK general election until 1959. In 1966 the first Plaid Cymru MP was returned to Parliament. Plaid Cymru's share of the vote since has averaged 10%, with the highest share ever - 14.3% - gained in the 2001 general election.[28] Plaid Cymru is strongest in rural Welsh-speaking areas of north and west Wales.

Liberal Democrats

The Welsh Liberal Democrats are part of the UK Liberal Democrats, and were formed by the merger of the Social Democratic Party (the SDP) and the Liberal Party in 1988. Since then they have gained an average vote share of 14% with the highest share - 18% - gained at the 2005 general election. The Welsh Liberal Democrats have the strongest support in rural mid and west Wales. The party performs relatively strongly in local government elections.

Senedd

Senedd Cymru or the Welsh Parliament, commonly known as the Senedd and formerly known as the National Assembly for Wales, is a devolved parliament with power to make legislation in Wales. The body meets in the Senedd building, on the Senedd estate in Cardiff Bay. Both English and Welsh languages are treated on a basis of equality in the conduct of business in the Senedd.

The present day Senedd was formed as the Assembly under the Government of Wales Act 1998, by the Labour government, following a referendum in 1997. The campaign for a 'yes' vote in the referendum was supported by Welsh Labour, Plaid Cymru, the Liberal Democrats and much of Welsh civic society, such as church groups and the trade union movement.[29] The Conservative Party was the only major political party in Wales to oppose devolution.[30]

The election in 2003 produced an assembly in which half of the assembly seats were held by women. This is thought to be the first time elections to a legislature have produced equal representation for women.[32]

The Senedd consists of 60 elected members. They use the title Member of the Senedd (MS) or Aelod o'r Senedd (AS).[33] The Senedd's Llywydd, or presiding officer, is Plaid Cymru member Elin Jones.

The Welsh Government is led by First Minister Mark Drakeford of Welsh Labour.[34]

The executive and civil servants are based in Cardiff's Cathays Park while the Members of the Senedd, the Parliamentary Service and Ministerial support staff are based in Cardiff Bay. The main debating chamber (known as 'Y Siambr' (the chamber)) and committee rooms are located in the £67 million Senedd building that was built in 2006.[35][36][37] The Senedd building is part of the Senedd estate that includes Tŷ Hywel and the Pierhead Building.

Until May 2007 one important feature of the Assembly was that there was no legal or constitutional separation of the legislative and executive functions, since it was a single corporate entity. Even compared with other parliamentary systems, and other UK devolved countries, this was highly unusual. In reality however there was day to day separation, and the terms "Assembly Government" and "Assembly Parliamentary Service" were used to distinguish between the two arms. The Government of Wales Act 2006 regularised the separation once it comes into effect following the 2007 Assembly Election.

The Senedd also has limited tax varying and borrowing powers.[38] These include powers over Business Rates, Land Transaction Tax (replacing Stamp Duty), Landfill Disposal Tax (replacing Landfill Tax) and a portion of Income Tax.

In terms of charges for government services it also has some discretion. Notable examples where this discretion has been used and varies significantly to other areas in the UK include:-

- Charges for NHS prescriptions in Wales - these have been abolished, while patients are still charged in England. Northern Ireland abolished charges in 2010, with Scotland following suit in 2011.[39][40]

- Charges for University Tuition - are different for Welsh resident students studying at Welsh Universities, compared with students from or studying elsewhere in the UK.[41]

- Charging for Residential Care - In Wales there is a flat rate of contribution towards the cost of nursing care, (roughly comparable to the highest level of English Contribution) for those who require residential care.[42]

This means in reality there is a wider definition of "nursing care" than in England and therefore less dependence on means testing in Wales than in England, meaning that more people are entitled to higher levels of state assistance. These variations in the levels of charges, may be viewed as de facto tax varying powers.

This model of more limited legislative powers is partly because Wales had a more similar legal system to England from 1536, when it was annexed and legally became an integral part of the Kingdom of England (although Wales retained its own judicial system, the Great Sessions, until 1830[43]). Ireland and Scotland were incorporated into the United Kingdom through negotiations between the respective Kingdoms' Parliaments, and so retained some more differences in their legal systems. The Scottish Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly have wider powers.

The Assembly inherited the powers and budget of the Secretary of State for Wales and most of the functions of the Welsh Office. After May 2007 the National Assembly for Wales had more extensive powers to legislate, in addition to the function of varying laws passed by Westminster using secondary legislation conferred under the original Government of Wales Act 1998. This was significantly enhanced after a referendum in 2011, and the Assembly had primary legislative powers over 20 areas, including Education and Health, from that time. This was changed again in 2018 to a system whereby certain powers were 'reserved to' Westminster, and everything not listed was within the powers of the Assembly. The post of Secretary of State for Wales, currently Simon Hart, retains a very limited residual role.

Welsh Government

The Welsh Government (Welsh: Llywodraeth Cymru), is the executive body of the Senedd, consisting of the First Minister and his Cabinet.

Following the 2021 Senedd election, a working majority Welsh Labour Government was formed in May 2021. The current cabinet members of the 11th Welsh Government consisting of members of the 6th Senedd are:

First Minister

- Rt Hon Professor Mark Drakeford MS (Labour)

Welsh Ministers[34]

- Rebecca Evans MS, Minister for Finance and Local Government (Labour)

- Eluned Morgan MS, Minister for Health and Social Services (Labour)

- Vaughan Gething MS, Minister for the Economy (Labour)

- Lesley Griffiths MS, Minister for Rural Affairs and North Wales, and Trefnydd (House Leader) (Labour)

- Jane Hutt MS, Minister for Social Justice (Labour)

- Julie James MS, Minister for Climate Change (Labour)

- Jeremy Miles MS, Minister for Education and Welsh Language (Labour)

- Mick Antoniw MS, Counsel General and Minister of the Constitution (Labour)

Deputy Welsh Ministers[44][45]

- Lynne Neagle MS, Deputy Minister for Mental Health and Wellbeing (Labour)

- Julie Morgan MS, Deputy Minister for Social Services (Labour)

- Dawn Bowden MS, Deputy Minister for Arts and Sport, and Chief Whip (Labour)

- Lee Waters MS, Deputy Minister for Climate Change (Labour)

- Hannah Blythyn MS, Deputy Minister for Social Partnership (Labour)

The Welsh Government had no independent executive powers in law - unlike for instance, the Scottish Ministers and Ministers in the UK government. The Assembly was established as a "body corporate" by the Government of Wales Act 1998 and the executive, as a committee of the Assembly, only had those powers that the Assembly as a whole votes to vest in ministers. The Government of Wales Act 2006 has now formally separated the Senedd and the Welsh Government giving Welsh Ministers independent executive authority.

Shadow Cabinet

Current party representation

Following the 2021 Senedd election:

| Party | MPs | MSs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labour | 22 of 40 | 30 of 60 | |

| Conservative | 13 of 40 | 16 of 60 | |

| Plaid Cymru | 3 of 40 | 12 of 60 | |

| Liberal Democrats | 0 of 40 | 1 of 60 | |

| Independent | 2 of 40 | 0 of 60 | |

Local politics

For the purposes of local government, Wales was divided into 22 council areas in 1996. These unitary authorities are responsible for the provision of all local government services, including education, social work, environment and roads services. Elections for these areas take place every five years, with the last elections having taken place in 2017 and the next due to take place in 2022. The lowest tier of local government in Wales is the community council, which is analogous to a civil parish in England.

The Queen appoints a Lord Lieutenant to represent her in the eight Preserved counties of Wales, which are combinations of council areas.

In January 2021, the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021 came into force. This among other measures extended the voting franchise to 16- and 17-year-olds and foreign citizens legally resident in Wales for local elections, made changes to voter registration and enabled principal councils to choose between the first-past-the-post (FPTP) or the single transferable vote (STV) voting systems.[46]

Contemporary Welsh law

Since the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542, Wales was annexed into England and has since shared a single legal system. England and Wales are considered a single unit for the conflict of laws. This is because the unit is the constitutional successor to the former Kingdom of England. If considered as a subdivision of the United Kingdom, England & Wales would have a population of 53,390,300 and an area of 151,174 km2.

Scotland, Northern Ireland, and dependencies such as the Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey, are also separate units for this purpose (although they are not separate states under public international law), each with their own legal system (see the more complete explanation in English law).

Wales was brought under a common monarch with England through conquest with the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 and annexed to England for legal purposes by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542. However, references in legislation for 'England' were still taken as excluding Wales. The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 meant that in all future laws, 'England' would by default include Wales (and Berwick-upon-Tweed). This was later repealed in 1967 and current laws use "England and Wales" as a single entity. Cardiff was proclaimed as the Welsh capital in 1955.

Westminster

In the UK Parliament

| This article is part of a series on |

| Politics of the United Kingdom |

|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) |

|

In the House of Commons – the 650-member lower house of the UK Parliament – Wales is represented by 40 members of Parliament (MPs) from Welsh constituencies. At the 2019 general election, 22 Labour and Labour Co-op MPs were elected, along with 14 Conservative MPs and 4 Plaid Cymru MPs.[47]

In the UK Government

The Wales Office (Swyddfa Cymru) is a United Kingdom government department. It is a replacement for the old Welsh Office (Swyddfa Gymreig), which had extensive responsibility for governing Wales prior to Welsh devolution in 1999. Its current incarnation is significantly less powerful: it is primarily responsible for carrying out the few functions remaining to the Secretary of State for Wales that have not been transferred already to Senedd and securing funds for Wales as part of the annual budget settlement.

The Secretary of State for Wales has overall responsibility for the office but it is located administratively within the Department for Constitutional Affairs. This was carried out as part of the changes announced on 12 June 2003 that were part of a package intended toward replacing the Lord Chancellor's Department.

There is also a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Wales.

Secretaries of State for Wales have included:

- David TC Davies MP (October 2022 – )

- Robert Buckland MP (July 2022 – October 2022)

- Simon Hart MP (December 2019 – July 2022)

European Union

The entire country of Wales was a constituency of the European Parliament. It elected four Members of the European Parliament using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation, representation had been reduced from five seats in 2004.

Members of the European Parliament for Wales 2019–2020[48]

- Nathan Gill, Brexit Party

- Jill Evans, Plaid Cymru

- James Freeman Wells, The Brexit Party

- Jacqueline Margarete Jones, Labour

In the 2016 Brexit referendum, Wales voted by a majority for Leave,[49][50] in all but five of its council areas,[51] with Remain having majorities in Cardiff, Monmouthshire, Vale of Glamorgan, Gwynedd and Ceredigion.[52] Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU, whereas England also voted for Leave.[53]

According to Danny Dorling, professor of geography at the Oxford University, "If you look at the more genuinely Welsh areas, especially the Welsh-speaking ones, they did not want to leave the EU."[54]

Intergovernmental relations

The Concordat on Co-ordination of European Union Policy Issues between the UK Government and the devolved administrations notes that "as all foreign policy issues are non-devolved, relations with the European Union are the responsibility of the Parliament and Government of the United Kingdom, as Member State".[55] However, Welsh Government civil servants participate in the United Kingdom Permanent Representation to the EU (UKRep),[56] and Wales is represented on the EU's Committee of the Regions and Economic and Social Committee.[57]

United States

Relations between Wales and America is primarily conducted through the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, in addition to her Secretary of Foreign Affairs and Ambassador to the United States. Nevertheless, the Welsh Government has deployed their own envoy to America, primarily to promote Wales-specific business interests. The primary Welsh Government Office is based out of the Washington British Embassy, with satellites in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Atlanta.[58]

US Congress Friends of Wales Caucus

Commensurately, the United States has established a caucus to build direct relations with Wales[59] comprising:

| House | ||

| Representative | Party | State |

|---|---|---|

| Morgan Griffith | Republican | Virginia |

| Kenny Marchant | Republican | Texas |

| Ted Lieu | Democratic | California |

| Doug Lamborn | Republican | Colorado |

| Jeff Miller | Republican | Florida |

| Keith Rothfus | Republican | Pennsylvania |

| Bob Goodlatte | Republican | Virginia |

| Charles W. Dent | Republican | Pennsylvania |

| Roger Williams | Republican | Texas |

| Senate | ||

| Senator | Party | State |

| Joe Manchin | Democratic | West Virginia |

| Executive | ||

| Secretary | Party | Office |

| Tom Price | Republican | Health and Human Services |

Political campaign groups and ideologies

Think tanks

Wales has typically been underserved by think tanks and research bodies relative to the rest of the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, a number of bodies exist across areas including the economy, social issues, housing, research, and more.

- Melin Drafod (est 2021), an independent think tank promoting Welsh Independence and answering 'practical questions' such as finance, currency and international relations. Supported by groups such as Cymdeithas yr Iaith, Yes Cymru, Undod and AUOB Cymru.

- Welsh Centre for International Affairs (est 1973) - established to promote the international exchange of ideas, build partnerships connecting Welsh people and global organisations, and encourage global action by Welsh people and groups.

- Institute of Welsh Affairs (est 1987) - a centre-right but 'independent' Welsh think tank.

- Gorwel (transl. Horizon, est 2012) - a cross-sector national and international ideas think tank founded by David Melding, Prof Russell Deacon, and Axel Kaehne.

- Bevan Foundation (est 2014) - a group debating social and economic problems, and solutions to inequality and injustice, founded by a number of people and previously led by Rowan Williams.

- WISERD (est 2014) - the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods.

- Public Policy Institute for Wales (2014–2017) - a former independent policy research institution based at Cardiff University.

- Wales Centre for Public Policy (est 2017) - an independent policy research institution focussed on public policy decision making, and based on the UK What Works network.

- Centre for Welsh Studies - (est 2017) a conservative, pro-Brexit, pro-free market think tank founded by Matthew Mackinnon.[69]

- Morgan Academy, Swansea University (est 2018) - a think tank named after former First Minister Rhodri Morgan and based within the Swansea University Public Affairs Institute. Previously led by Helen Mary Jones.

- Nova Cambria (est 2019) - an arms-length Plaid Cymru backed think tank and journal aimed at achieving a Plaid Cymru majority at the 2021 Senedd election.

Political media outlets

- BBC Wales Politics

- Betsan Powys's blog, BBC Wales' political editor

- David Cornock's blog, BBC Wales' parliamentary correspondent

- Vaughan Roderick's blog (in Welsh), BBC's Welsh affairs editor

- Wales Online Politics – from the Western Mail and its sister publications

- Cambria – Current affairs magazine

- Barn – Welsh language current affairs magazine

- Nation.Cymru - Current affairs website

- Senedd Home - Current affairs blog

See also

References

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (2003). Decentralizing the civil service : from unitary state to differentiated polity in the United Kingdom. Buckingham: Open University. p. 107. ISBN 9780335227563.

- Jones, Francis (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales P. ISBN 978-0-900768-20-0.

- Gower, John (2013). The Story of Wales. BBC Books. pp. 137–146.

- Davies, R. R. (1995). The revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0198205081.

- Williams, Glanmor (1993). Renewal and Reformation: Wales C. 1415-1642. Oxford University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-19-285277-9.

By making the Welsh citizens of the realm it gave them equality under the law with English subjects," and speaking of the Welsh people, "At last they had had their wish and been granted by statute the full 'freedoms, liberties, rights, privileges and laws' of the realm. By conferring upon them legal authorization to become members of parliament, sheriffs, justices of the peace, and the like, the Act had done little more than give statutory confirmation of rights they had already acquired de facto. Yet, in formally handing power to members of the gentry, the Crown had conferred self-government upon Wales in the sixteenth-century sense of the term.

- Williams, Glanmor (1993). Renewal and Reformation: Wales C. 1415-1642. Oxford University Press. p. 268-73. ISBN 978-0-19-285277-9.

- Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- Morgan 1981

- Butt-Phillip 1975

- Davies 1994, p. 622

- "Labour Party Wales Archives - National Library of Wales Archives and Manuscripts". archives.library.wales. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- Davies 1994

- The road to the Welsh Assembly from BBC Wales History website. Retrieved 23 August 2006. Archived 21 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Davies 1994, p. 667

- Devolution in the UK: Department for Constitutional Affairs. UK State website. Retrieved 9 July 2005.

- The 1979 Referendums: BBC website. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- McLean, I. "The National Question" in Seldon, A., ed. (2007) Blair's Britain 1997-2007. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Across the clear red water, by Steve Davies. Public Finance 23-05-2003

- "Welsh Government-News". wales.gov.uk.

- "Drop in hospital waiting times". 29 May 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Osmond, J. (2008) Cardiff Bay Papers No. 1: Unpacking the Progressive Consensus. Institute of Welsh Affairs

- BBC NEWS | Wales | "Axe fear for free prescriptions", 30 April 2009

- Mortimer, Josiah (1 June 2020). "16 and 17 year olds have secured the right to vote in Wales". electoral-reform.org.uk. The Electoral Reform Society. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Jones, B, Welsh Elections 1885 - 1997 (1999), Lolfa. See also UK 2001 General Election results by region, UK 2005 General Election results by region, 1999 Welsh Assembly election results Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, 2003 Welsh Assembly election results and 2004 European Parliament election results in Wales (BBC) Archived 2 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Waleslabourparty.org.uk". www.waleslabourparty.org.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- Jones, B, Welsh Elections 1885 - 1997(1999), Lolfa

- "Cameron hails 'historic' victory". BBC News. 8 June 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Jones, B, Welsh Elections 1885 - 1997 (1999), Lolfa. See also UK 2001 General Election results by region, UK 2005 General Election results by region Archived 2 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Andrews 1999

- The Politics of Devolution - Party policy: Politics '97 pages, BBC. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- "First Welsh law's royal approval". 9 July 2008 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Women win half Welsh seats: By Nicholas Watt, The Guardian, 3 May 2003. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Hayward, Will (6 May 2020). "The Welsh Assembly is now a Parliament - this is what AMs are now called". walesonline. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Cabinet Members". Welsh Government. 20 March 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- National Assembly for Wales and Welsh Assembly Government Archived 14 February 2006 at the UK Government Web Archive in Guide to government: Devolved and local government, Directgov, UK state website. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- Assembly Building: Welsh government website. Retrieved 2006-07-13. Archived 8 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- New assembly building opens doors: BBC News, 1 March 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- "Tax is changing in Wales". GOV.UK. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Q and A: Welsh prescription prices: BBC News, 1 October 2004. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- NHS Wales - NHS prescription charges Archived 7 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Q&A: Welsh top-up fees: BBC News, 22 June 2005. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- "NHS Continuing Care - Commons Health Select Committee", News and Views - NHFA. Retrieved 2006-11-10. Archived 25 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Williams 1985, p. 150

- "Deputy Ministers". Welsh Government. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Janice Gregory". National Assembly for Wales. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021". Welsh Parliament. 18 November 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Jones, Ciaran (9 June 2017). "These are the 40 MPs who have been elected across Wales". Wales Online.

- "European Election 2009: Wales". BBC News. 8 June 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Jones, Moya (16 March 2017). "Wales and the Brexit Vote". Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique. French Journal of British Studies. 22 (2). doi:10.4000/rfcb.1387. S2CID 157233984. Retrieved 19 October 2021 – via journals.openedition.org.

- Mosalski, Ruth (17 November 2019). "How every Welsh constituency voted in the EU referendum". WalesOnline.

- Dunin-Wasowicz, Roch (2 August 2016). "Wales, already impoverished, is set to get even poorer". London School of Economics. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- "EU referendum results by region: Wales". Electoral Commission. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- "EU Referendum Results - BBC News". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "English people living in Wales tilted it towards Brexit, research finds". The Guardian. 22 September 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- "Concordat on Co-ordination of European Union Policy Issues". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 January 2008.

- "United Kingdom Permanent Representation to the EU (UKRep)". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- "EU Advisory Committees". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- "USA". www.wales.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Congressional Friends of Wales Caucus Welcomes First Minister Carwyn Jones". U.S. House of Representatives. 6 September 2016.

- "Cornwall joins Scotland and Wales in marching All Under One Banner". Nation.Cymru. 30 May 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "Labour supporters lay out vision of independent Wales". The National Wales. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Ellis, John Stephen (2008). Investiture: Royal Ceremony and National Identity in Wales, 1911-1969. University of Wales Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-7083-2000-6.

- "Extra bank holiday for St David's Day Notice of Motion not supported | tenby-today.co.uk". Tenby Observer. 23 June 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "Why Unionism in Wales will be harder to budge than YesCymru may think". Nation.Cymru. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "'Wales for the Assembly' Campaign - Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "The Politics Of Welsh Independence - Could It Ever Happen?". Politics.co.uk. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "Welsh Republican Movement/Mudiad Gweriniaethol Cymru - National Library of Wales Archives and Manuscripts". archives.library.wales. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "YesCymru EN". YesCymru EN. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Martin Shipton (28 November 2020). "Controversial US Group helped fund Welsh think tank". Western Mail.

Bibliography

- Andrews, Leighton (1999). Wales says yes: the inside story of the yes for Wales referendum campaign. Bridgend: Seren.

- Butt-Phillip, A. (1975). The Welsh Question. University of Wales Press.

- Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-014581-8.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1981). Rebirth of a Nation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198217367.

- Williams, Gwyn Alf (1985). When Was Wales?. Black Raven Press.