Whaling in Madagascar

Whaling in Madagascar is currently banned on a commercial level in compliance with sanctuary regulations. Despite erratic weather conditions, there is a history of overhunting sperm whales, humpback whales, and Bryde's whales within the surrounding waters of Madagascar. In an attempt to allow native populations to recuperate from these operations, the region about Madagascar was included within the Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary by the International Whaling Commission.

History

Two major currents influence the migration patterns of humpback whales on the coasts of Madagascar. The south branch of the South Equatorial Current meets at the south of Madagascar and travels up the western coast, forming the East Madagascar Current. Similarly, the Madagascar Ridge migratory route travels through currents traveling north along the east coast.[1] Studies of humpback mating behavior have conjectured that Antongil Bay, on the northeast of the island, may be a wintering and mating site.[2] This may explain why American and British whaling records show records of whale hunting as early as the 1830s in the Indian Ocean, concentrated at Antongil Bay.[3] This was predated by native traditional whaling; the artist Theodor De Bry depicted Madagascans whaling as early as 1598.[4]

Whaling in Madagascar began on an industrial level as a northward expansion of the sperm whaling trade off the Cape of Good Hope around 1800.[5] Christian Salvesen & Company of Leith, which held more whaling shares than any other single firm, operated briefly off Madagascar. After dispatching the factory ship Horatio, yields were so low that Salvesen totaled deficits from 1911 to 1913. Adding insult to injury, while docked at Leith Harbour, the Horatio caught fire, with 11,000 barrels of oils on board.[6]

France was criticized for its actions at the 1949 meeting of the International Whaling Commission when they continued the use of floating factories in French territorial waters off of Madagascar, despite rules prohibiting floating factories north of 40° South. France's decision to continue using the floating factory Jarama is credited with the depletion of humpback whale populations surrounding Madagascar.[6]

Climate and currents

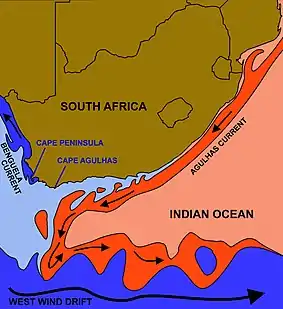

In South Africa, weather patterns are inconsistent. People who live in Madagascar have learned to deal with these conditions. The Agulhas Current is a root cause of these sporadic conditions. Along the South African coast, near Madagascar, the oceanic current, when mixed with a cold front, can cause freak waves that can destroy ships.[7] This current is the largest current to follow adjacent to a continent for that distance. Being on the border of the Indian Ocean gyre, the intense ranges of water temperatures can result in major storms. Tropical storms that have turned into recorded cyclones, have caused billions of dollars worth of damages. Each cyclone originally forming from the north-eastern coast of the African continent, and slowly accumulating down the coast, where its energy accumulates the most. The storms that result from combining warm and cold temperatures have a huge affect in the northern region of the Agulhas Current.[8] As it goes down the continent of Africa, the atmosphere becomes warmer, and the weather mellows out into a steady rainfall, giving South Africa and West Madagascar humidity and storms. Another factor contributing to weather conditions in the South African- Madagascar region is the contribution of the South Equatorial Madagascar Current. This particular current travels westward from the Indian Ocean, hitting the east coast of Madagascar. This can be a challenge for ships traveling on the east coast of Madagascar because instead of being able to follow the oceans strong general current, they would have to fight it, no matter which way they were traveling. As the SEMC continues South Equatorial Madagascar Current hits Madagascar, the current changes position southward, where it meets up with the stronger Agulhas current, creating conflicting currents that can be a huge hassle for anyone trying to navigate those waters.[9]

Data collection

To gain better research and knowledge about these climate changes, buoys are cast out to sea where they are located by satellite. The satellite pics up these frequencies sent out by the buoys drifting in the ocean off the continental coast, producing much needed data to increase predictability. Original technology of the buoy can date back thirty years, but with advancements in technology, the data collected nowadays do not just focus on the oceanic currents. Information gathered can reflect the wind patterns, temperatures, and certain densities of the ocean in specific areas, as all these factors are constantly fluctuating. These buoys are located all over the world, oceans and great lakes. The data collected goes to the National Data Buoy Center, where experts record and analyze the feedback. With relation to wave currents, the buoys use accelerometers that can identify the directional vector of the waves. They also record the special distance between the trough and crest of each wave. This information that is constantly used by sailors, can be life saving and result in a more efficient trip across the sea.[10]

2008 Mass stranding

A mass stranding of around one hundred Melon-Headed whales (Peponocephala Electra) occurred in the Loza Lagoon system of Northwest Madagascar during the months of May and June in 2008. Of the original whales that entered the lagoon system, seventy five died from causes related to being out of their normal deep sea habitat. At the time of the event many marine experts, conservation organizations, and other groups surveyed the area to collect data on this event. The International Whaling Agency (IWC) and other federal agencies with the permission of the Madagascar Government launched an investigation into the cause of this mass stranding. The IWC concluded that the most plausible trigger for the event was a high power 12 kHz multi-beam echosounder system (MBES) that has been firing along a shelf break a day before the event.[11]

Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary

Madagascar lies entirely in the Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary, a whale sanctuary that covers the Indian Ocean south to 55º S. The sanctuary prohibits commercial whaling and aims to facilitate the recovery of whale populations, allow whales to do their jobs within the ecosystem, and foster public awareness. This sanctuary's conservation efforts are uniquely important for several reasons. The sanctuary allows for the Sperm whale and the Oman Humpback whale to recover their population which has been diminished by illegal soviet whaling operations in the 70's. The sanctuary also allows the population recovery of the Bryde's whale from Japanese whaling operations which still continue to this day as Japan does not respect the sanctuary and continues its operations claiming that their operations are purely scientific. Approximately 600 whales are killed each year by Japanese scientific whaling operations.[12]

The sanctuary was established in 1979 and has been renewed for ten year periods in 1992 and 2002. In 2001 during the Nairobi convention the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) pledged their support of the sanctuary, stating the convention “Reaffirmed the need to maintain the status of the Indian Ocean as a sanctuary for the protection of endangered marine mammals of the convention region.”[13]

References

- MN De Boer; R Baldwin; CLK Burton; EL Eyre (2002). "Cetaceans in the Indian Ocean Sanctuary: a review". Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS): UK.

- Hart, Terese; Hart, John; Fimbel, Cheryl; Fimbel, Robert; Laurance, William F.; Oren, Carrie; Struhsaker, Thomas T.; Rosenbaum, Howard C.; Walsh, Peter D. (1997-01-01). "Conservation and Civil Strife: Two Perspectives from Central Africa". Conservation Biology. 11 (2): 308–314. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.011002308.x. JSTOR 2387605.

- Razafindrakoto, Yvette (2001). "FIRST DESCRIPTION OF HUMPBACK WHALE SONG FROM ANTONGIL BAY, MADAGASCAR". Marine Mammal Science. 17 (1): 180–186. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb00990.x.

- George Francis Dow (21 February 2013). Whale Ships and Whaling: A Pictorial History. Courier Corporation. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-486-17030-5.

- William F. Perrin; Bernd Wursig; J.G.M. 'Hans' Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 609–. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- Johan Nicolay Tønnessen; Arne Odd Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press. pp. 654–. ISBN 978-0-520-03973-5.

- Roberts, Lutjeharms (January 15, 1988). "A Natal Pulse: An Extreme Transient on the Agulhus Current" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 93 (C1): 631. Bibcode:1988JGR....93..631L. doi:10.1029/jc093ic01p00631.

- "The Agulhas Current Retroflection" (PDF).

- Sielder, Rouault (2009). "Modes of the southern extension of the East Madagascar Current" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (C1). Bibcode:2009JGRC..114.1005S. doi:10.1029/2008JC004921.

- "Buoys and Drifters". Ocean Motion.

- Southall, Brandon; Rowles, Teri; Gulland, Frances; Baird, Robin; Jepson, Paul. "Final report of the Independent Scientific Review Panel investigating potential contributing factors to a 2008 mass stranding of melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra) in Antsohihy, Madagascar" (PDF). Retrieved May 2nd, 2016.

- "Whale Sanctuaries". International Whaling Commission. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "IFAW Summary Briefing: Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary" (PDF). International Fund for Animal Welfare. Retrieved 2 May 2016.