Wham Paymaster robbery

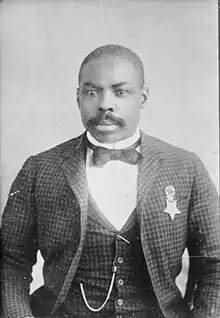

The Wham Paymaster robbery (/ˈhwɑːm/ WHAHM) was an armed robbery of a United States Army paymaster and his escort on May 11, 1889, in the Arizona Territory. Major Joseph W. Wham was transporting a payroll consisting of more than US$28,000 (equivalent to $911,970 in 2022) in gold and silver coins from Fort Grant to Fort Thomas when he and his escort of eleven Buffalo Soldiers were ambushed. During the attack, the bandits wounded eight of the soldiers, forced them to retreat to cover and stole the payroll. As a result of their actions under fire, Sergeant Benjamin Brown and Corporal Isaiah Mays were awarded the Medal of Honor while eight other soldiers received a Certificate of Merit. Eleven men, most from the nearby Mormon community of Pima, were arrested, with eight of them ultimately tried on charges of robbery. All of the accused were found not guilty, and the stolen money was never recovered.

| Wham Paymaster robbery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Holding Up the Pay Escort by Frederic Remington | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Gilbert Webb (alleged) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12 infantrymen | 7–13 bandits | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8 wounded | 1–2 killed (suspected) | ||||||

Background

In April 1889, Special Order 37 directed all paymasters in the District of Arizona to pay troops mustered as of April 30.[1] Major Joseph Washington Wham, a U.S. Army paymaster, was assigned Fort Bowie, Fort Grant, Fort Thomas, Fort Apache and Camp San Carlos.[2] Wham and his clerk, William T. Gibbon, met a train carrying the payroll in Willcox on May 8.[3] The paymaster performed his duties at Fort Bowie on May 9 and at Fort Grant on May 10.[4]

Early on May 11, Major Wham left Fort Grant with two mule-drawn carriages, a covered ambulance and an open wagon, for the 46-mile (74 km) journey to Fort Thomas. The remaining payroll consisted of US$28,345 in gold and silver coins and weighed an estimated 250 pounds (110 kg).[3]

The commander of Fort Grant had assigned eleven enlisted Buffalo Soldiers from the 24th Infantry and 10th Cavalry to serve as an escort between his fort and Fort Thomas. In addition to the military personnel, there was a civilian contractor who drove the open wagon. The two non-commissioned officers leading the escort were armed with revolvers while the privates carried single-shot rifles and carbines. Wham and the civilian members of the convoy were unarmed. Accompanying Wham on the journey was a black woman, Frankie Campbell (also known as Frankie Stratton), who was the wife of a soldier stationed at Fort Grant and was going to collect gambling debts owed to her and her husband by soldiers stationed at Fort Thomas.[5]

There had never been an attack by highwaymen upon a paymaster within Arizona Territory prior to May 1889.[4] Despite this, there were several factors favoring such an attack. At the time, the territory was remote and had only a small and scattered population. Many residents of Arizona Territory held the U.S. federal government in low regard, feeling it ruled the territory from Washington with little interest in the territorial residents' well-being. Compounding this was the fact that most white residents of Arizona had been either Confederates or Confederate sympathizers during the American Civil War.[6] Decades of hostilities between Washington and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints left hard feelings among the territory's Mormon population.[7] Recent efforts to enforce the Edmunds Act, which made polygamy a felony, had increased anger among this group.[8] Finally, strong racial biases held by the white population against black soldiers may have been exacerbated by Mormon teachings that placed blacks on a "lowly rung of the social ladder". This led to a situation where some area residents could have rationalized that the payroll would have been better spent supporting the local communities instead of in the hands of black soldiers, who were seen as likely to spend it on immoral pursuits.[7]

The road to Fort Thomas went southwest to the town of Bonita before turning north and following the western side of Mount Graham.[5] About 25 miles (40 km) from Fort Grant the road entered a pass leading to the Gila River valley. Wham's convoy reached Cedar Springs, in the pass, around noon and swapped their mules for a fresh set that were waiting at the NN ranch. Campbell, whose horse was faster than Wham's wagons, waited at a stagecoach half-way station a short distance further down the road. The station was operated by Mormon polygamist Wiley Holladay.[9] Holladay was away that day, leaving his wives, Harriet and Eliza, to run the place.[10] Wham and his escort reached the station around 12:45 pm, at which time Campbell rejoined the group.[9]

Robbery

The site of the attack was about 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the stagecoach station.[4] The road at that point descended from a high ridge through a narrow gorge to a creek bed.[11] The east side of the gorge consisted of a steep, rocky slope rising about 50 feet (15 m) above the road with a lower rise on the western side.[12] Along the top of the eastern side a series of breastworks had been constructed by the bandits.[11] In an apparent attempt to make the fortifications appear more daunting, yucca stalks were fashioned to look like rifle barrels and positioned in the breastworks.[13] At about 1:00 pm, the Wham party reached the site of the attack. Campbell, who was in the lead, was attempting to guide her horse around a boulder that was blocking the road as the rest of the party crested a hill.[14] After the convoy halted, Sergeant Benjamin Brown led his men forward to try to move the obstacle out of the road while Corporal Isaiah Mays took a position at the rear of the convoy.[15] As they approached the rock, the group saw evidence that the rock had been deliberately placed in the road. As they then looked up to see where the rock had come from, the soldiers saw two men stand up from a breastwork situated above them.[16] Neither of the two men wore masks and the soldiers later identified their attackers as Wilfred T. Webb and Mark E. Cunningham. Local folklore suggests some bandits may have donned disguises, with one attacker dressed to resemble a local figure named William Ellison "Cyclone Bill" Beck. [17] Cunningham was armed with a rifle. Webb brandished a pair of revolvers and yelled, "Get out, you black sons of bitches!"[16] The bandits then began to fire toward the convoy.[16]

The first volley from the attackers killed three mules and wounded the ambulance driver.[11] The wounded ambulance driver dragged himself to a dry creek bed about 170 feet (50 m) away.[18] The bandits apparently held a condescending opinion of the Buffalo Soldiers' fighting ability and thought they could be easily defeated.[13] This likely played a part in the opening moments of the battle with the attackers firing mostly over the heads of the Buffalo Soldiers in an effort to scare them away. It was not until the military escort began to provide a determined resistance that the attackers began to shoot directly at the soldiers.[11] The civilian driving the open wagon abandoned his vehicle as the gunfight began, fleeing to safety. Campbell's horse spooked at the sound of the weapons and threw her before it ran back toward the stagecoach station.[18]

The bandits called Campbell's name and fired a couple shots in her direction before turning their attention elsewhere. Campbell then crawled behind a bush and some rocks located about 50 feet (15 m) past the ambulance. She observed the rest of the fight from this position.[19] The soldiers, who had set their rifles down while preparing to move the boulder, quickly grabbed their weapons and ran for cover.[4] Brown and two privates were separated from the rest of the group and forced down the road. After finding cover, Brown, though wounded in his arm, fired his revolver at the bandits that had stood up. After emptying his revolver, he took a rifle from one of the privates and continued the fight. It was not until one of the two privates was wounded, and the sergeant shot a second time, that the three men retreated to a dry creek bed about 300 feet (91 m) away.[20] Major Wham initially took shelter behind the ambulance.[19] The remaining draft animals panicked at the sound of the gunfire and dragged both wagons off the west side of the road, damaging their harnesses in the process.[21] This forced Wham to retreat behind a small rocky ledge on the west side of the road. He was joined behind the outcropping by his clerk and most of the soldiers. Wham directed the soldiers' fire while his clerk rendered aid to the wounded. Both men, initially unarmed, later took rifles from wounded soldiers and joined in the fight.[19]

Mays initially returned fire with his revolver from behind the escort wagon. This position soon proved untenable and he joined Wham behind the rocky ledge.[22] While Wham and his men were pinned down there, the bandits maneuvered along the top of the ridge to get them into a crossfire.[12] About 30 minutes after the battle began, Mays, who had assumed command of the escort following the withdrawal of Brown, informed Wham that their position was no longer defensible and that he was ordering his men to withdraw. Wham initially objected to this choice but later admitted that Mays had made the correct military decision.[23] From the rocky ledge, Wham and Mays withdrew to the nearby dry creek bed. There Wham attempted to rally the soldiers to retake the lock box holding the payroll, but after seeing that eight of the eleven soldiers were wounded realized that was not a viable option.[24] With the soldiers located about 300 yards (270 m) from their initial defensive position, the bandits continued to fire at them. With the soldiers pinned down, several of the bandits descended the hill and opened the strongbox holding the payroll with an axe.[25] At about 2:30 pm the bandits stopped firing and left in two groups. The first group led a mule carrying what appeared to be a man slumped over it and the second group provided cover for the first.[26]

It was not until around 3:00 pm that the soldiers returned to the ambulance and Campbell left her hiding place.[26] They discovered the nine surviving mules had run off during the attack and their harnesses had been cut to pieces.[11] As the soldiers returned to the ambulance, Harriet Holladay arrived on the scene in her buckboard. She had heard the gunfire and decided to investigate when Campbell's riderless horse arrived at the station house. Upon her arrival she joined with Campbell to provide first aid to the wounded soldiers.[26] Four of the mules were located by the nearby creek bed and the soldiers were able to splice together enough of the harnesses to hitch them to the ambulance.[11] Most of the wounded were loaded into the ambulance for transport to Fort Thomas. Sergeant Brown and one other man were deemed too severely injured to move and were tended by Campbell until the surgeon from Fort Thomas could be dispatched to retrieve them.[27] As the convoy was preparing to leave, rancher Barney Norton, who had also heard the sounds of the battle, arrived with a group of his ranch hands.[26] Wham arrived at Fort Thomas at about 5:30 pm.[27]

Investigation

Before leaving the site of the attack, Wham conducted an initial investigation of the immediate area. A valise containing the major's personal items, which had been stored in the strongbox, had been cut open, but the robbers had left the contents undamaged. A second valise, containing payroll receipts from his previous stops, had been taken along with the money. An examination of the breastworks on top of the ridge found one of the fortifications contained over 200 spent rifle casings.[26] Wham also arrested Campbell at the site of the attack, believing she had somehow been involved. She was released a short time later and became an important witness for investigators.[27]

After Wham arrived at Fort Thomas, a contingent of soldiers was sent to guard the scene of the attack until a complete sketch of the site could be completed.[27] Troops stationed throughout the southern Arizona Territory were also deployed in an effort to prevent the robbers from escaping into Mexico.[4] At about 10:00 AM on May 12, Graham County Sheriff Billy Whelan Sr., accompanied by several deputies and a group of Buffalo Soldiers, attempted to follow the bandits' trail. Local lore claims the robbers fled southward until they passed through a herd of horses several miles from the attack site. There they divided the loot and went in separate directions.[27] The sheriff eventually found a trail leading toward the Gila River that led to the Follet Ranch. The portion of the trail leading to the river appeared to have been made by horses that had had their horseshoes attached backwards. The shoes were then removed at the river in a further effort to confuse the trail.[28] Additional trails leading to other ranches were discovered on May 13. The sheriff asked the residents of these ranches about their whereabouts on May 11. "The ranchers", Deputy Billy Whelan Jr. later described, "hemmed and hawed and tried to make us think they were at other places. But the buffalo soldiers identified them."[29]

Meanwhile, the valise containing the payroll receipts was located about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the ambush site with the pay stubs covered in blood.[11] Based upon this evidence and reports by Campbell and Wham's clerk that the bandits had carried away what had appeared to be a man's body on a mule, it was assumed that one or two of the attackers had been killed during the battle. No body was ever discovered, however, and no missing persons reports for people living in the area were ever received by local authorities.[29] On May 13, 1889, Governor Lewis Wolfley announced a $500 reward for the arrest and conviction of one or more of the bandits.[30] The United States Marshal for Arizona, William K. Meade, also joined in the investigation. Based upon the initial findings, Meade and Sheriff Whelan focused their investigation on the area around Pima, Arizona Territory.[29] Numerous arrests were made but most of the arrested men were soon released due to a lack of evidence.[31]

Reaction to events in the predominantly Mormon town of Pima was divided into two camps. About half the town was generally cooperative with the investigation. The other half viewed it as a return to federal persecution. The wife of the owner of the Pima Hotel summarized this sentiment by saying, "It's just following the usual pattern. From the time I first learned of the robbery I have expected nothing else than that it would be laid on to the Mormons."[32] The opposition even accused deputy marshals of planting gold coins found in the possession of prominent church members and making indiscriminate arrests in an effort to collect reward money.[8] Marshal Meade arrested M. E. Cunningham based upon information provided by Frankie Campbell.[33] This was soon followed by the arrests of Ed Follett, Lyman Follett, Warren Follett, Thomas N. Lamb, David Rogers, Siebert Henderson, Gilbert Webb, and Wilfred Webb on May 13.[8][32] William Ellison "Cyclone Bill" Beck was also arrested soon after the robbery. While waiting in Tucson for his alibi to be confirmed, Beck began drawing the attention of the locals. Enough visitors came to see him that he began charging a fee for the viewings of "the raw head and bloody bones of the Gila Valley" and claimed he "could make enough money to pay all my expenses in this damn trial".[34] Beck's alibi was confirmed and he was released from custody.[31] Henderson and Ed Follett were likewise released due to a lack of evidence.[32] During a preliminary hearing before Magistrate L. C. Hughes, none of the others were able to provide an alibi and only Gilbert Webb was able to post bail.[35]

The suspected ringleader was Gilbert Webb, who was also the serving mayor of Pima and a leading member of the Graham County Democratic party.[36] He was held in high regard within the Mormon community due to the jobs he provided through his various businesses.[36] Non-Mormon neighbors of Webb had a less generous view of the man, noting he had left Utah a decade earlier to avoid charges of grand larceny.[37] There was also a pattern of property disappearances that seemed to occur near places the Webb family had lived or worked. During the six years preceding the robbery, Webb had experienced some financial setbacks that had forced him to close his store and sell his stagecoach line. He had recently obtained a contract to provide straw and grain to Fort Thomas and San Carlos but may have lacked the needed financial resources to raise these crops. Webb's lack of the short-term capital needed to meet his end of this contract was a possible motive for the robbery.[6] While he was out on bail, Webb spent his time searching for witnesses willing to testify on behalf of him and his fellow defendants.[38]

While most of the accused were not active members of the LDS Church, they were all related to active church members and all considered to be outstanding members of the community.[39]

Trial

A U.S. federal grand jury was convened in Tucson in late September 1889. They soon began investigating the Wham robbery with an estimated 65 witnesses, many from Graham County, testifying before them.[40] The grand jury issued indictments against the eight remaining suspects on the charge of robbery on September 27, 1889.[41] Following the indictments, Judge William H. Barnes, who was a personal friend of one of the defendants, reduced the defendant's bail from $15,000 to $10,000.[42] This prompted United States Attorney Harry R. Jeffords to call for the judge's removal.[38] The grand jury members, concerned the judge's actions in court had intimidated some of the prosecution witnesses, sent a telegraph to the Department of Justice asking for a judge other than Barnes to preside over the trial.[43] The grand jury members were unaware that Barnes had already made arrangements for Judge John J. Hawkins to preside over the trial. Upon learning of the telegram, Judge Barnes dismissed the grand jury, calling them "a band of character assassins, unworthy to sit in any court of justice".[44] A few days after the telegram was sent, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Richard E. Sloan to replace Barnes.[45]

Pre-trial shenanigans did not stop at the courtroom. Three horses were shot and multiple heads of cattle were stolen from the defendants and their friends. Ed Follett was arrested for trying to intimidate a prosecution witness into changing his testimony. Finally, the Solomonville district court clerk and former Graham County sheriff, Ben M. Crawford, was forced to resign.[45] He was later indicted for securing witnesses who gave false testimony in support of the defense.[46] These events set the scene for a tumultuous trial.[47] The trial began in Tucson on November 11, 1889.[47] U.S. Attorney Jeffords led the prosecution while Mark Smith and Ben Goodrich led the defense.[48] There were 165 witnesses called during the trial, over half by the defense.[44] During his testimony, Wham identified three of the defendants, Gilbert Webb, Warren Follett, and David Rodgers, as being among the attackers who performed the robbery.[49] Wham also identified gold coins that had been deposited into a hotel safe by Webb as being some of the stolen coins.[48] Identification of the coins was based upon unusual patterns of discolorations present upon them.[49]

During cross-examination, Smith challenged the identification of the coins by mixing in several coins from a local bank. Wham was embarrassed by his inability to differentiate between the coins from the bank and those he claimed had come from the robbery.[48] Frankie Campbell also gave testimony.[47] Smith vigorously cross-examined each of the prosecution witnesses, leading many to admit that they had not had clear views of the attackers.[50] Compounding difficulties for the prosecution were differences in the slang used by the black witnesses and the white jurors. This, combined with a reluctance by many area residents to condemn a man based upon the word of a former slave, may have caused the jury to minimize the validity of the prosecution's case.[51] The defense provided a series of witnesses, described as "brothers, sisters, cousins, and aunts of each other and the defendants", to provide alibis for the accused. Due to the conflicting testimony provided by various witnesses, the defense took five hours for their closing arguments. Smith used this time to play upon the biases and prejudices of the jury.[48] He argued that the robbers had dressed in a manner similar to his clients in order to misdirect suspicion upon them and that the robbers had fled to Mexico immediately after the robbery. Then he pointed out that U.S. Marshal Meade had failed to go to the scene of the attack to look for any trail left by the attackers. Smith also claimed the government officials who arrested his clients were more interested in the reward money for capturing the robbers than in finding the people who actually committed the crime.[52] When Smith began to question the integrity of the court, Judge Sloan threatened him with a $500 fine for contempt.[53]

The jury deliberated for two hours before delivering a not guilty verdict.[52][54] Deputy William "Billy" Breakenridge noted after the trial, "the Government had a good case against them [the robbers], but they had too many friends willing to swear to an alibi, and there were too many on the jury who thought it no harm to rob the Government."[50]

Later events

The general reaction to the verdict was one of shock and amazement.[52] In response to public reaction to the quick verdict, the jury issued a statement saying, "We were present during the entire time of the trial, we heard everything that was said and saw everything that was done in the courtroom and heard nothing of what was being done and said outside, hence when we had agreed upon a verdict we did not know of anything to keep us in the jury room longer."[55] A misunderstanding of the jury instructions may have also played a role in the verdict. The jury's understanding of the instructions was that they were required to find all of the defendants guilty in order to convict, and as they could not agree that all eight were involved, they felt required to return a not guilty verdict.[55]

U.S. Attorney Jeffords became seriously ill shortly after the trial and died several months later.[56] Major Wham in turn was held responsible for the lost funds. He was relieved of this debt on January 21, 1891, when the U.S. Congress passed an act relieving him of responsibility.[57] Smith, who had ignored his duties as territorial delegate to take the case, was attacked politically for his involvement.[52] This left the majority of the blame for the failed prosecution on U.S. Marshal Meade.[50] Meade was replaced as U.S. Marshal on March 4, 1890. His successor, Robert H. "Bob" Paul, adopted a watch and wait philosophy hoping a $500 reward offered by the Department of Justice at the urging of the War Department would lead to a resolution of the case.[58] In August 1892, the Department of Justice asked the U.S. Attorney to investigate charges that the jury had been bribed during the Wham trial.[58] In recognition for their actions during the robbery, Sergeant Benjamin Brown and Corporal Isaiah Mays were awarded the Medal of Honor. Additionally, privates George Arrington, Benjamin Burge, Julius Harrington, Hamilton Lewis, Squire Williams, Jason Young, Thorton Hams, and Jason Wheeler were each awarded a Certificate of Merit.[59]

Legal troubles for the accused did not end with their acquittal. In May 1890, Cunningham, Lyman Follett, and Warren Follett were arrested by Graham County officials on charges of cattle rustling. They were convicted of the charges and sentenced to two years in prison.[58] An appeal of the conviction reached the Arizona Territorial Supreme Court, which granted them a new trial. The prosecution dropped the charges before the second trial could convene.[57] Meanwhile, Gilbert and Wilfred Webb were accused of defrauding the Graham County school district.[58] Wilfred Webb survived the accusations and later became active in territorial politics, serving as Speaker of the House during the 23rd Arizona Territorial Legislature and as a member of Arizona's constitutional convention.[57] When asked if he was involved in the robbery, he responded with "Twelve good men said I wasn't".[56] At the time of his death, Webb owned the 76 Ranch. The ranch measured 20 by 50 miles (32 by 80 km) and included all of Mount Graham.[56] The money taken during the robbery has never been recovered.[60]

References

Citations

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 101.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 101–112.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 102.

- "A Battle with Brigands". The Anderson Intelligencer. Anderson Court House, South Carolina. May 23, 1889. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 103.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 107.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 108.

- Ball 1999, p. 177.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 104.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 104–106.

- "An Interview – With Major Wham Giving Full Particulars of the Famous Hold-up on the Fort Thomas Road". Arizona Weekly Citizen. Tucson, Arizona Territory. May 25, 1889. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- "They Fought Nobly – But the Robbers Were Too Much for Paymaster Wham's Party". Evening Star. Washington, D. C. May 14, 1889. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 110.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 111.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 111–112.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 112.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 110–112.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 113.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 114.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 115.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 112–113.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 116.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 117.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 117–118.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 118.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 119.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 120.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 120–121.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 121.

- "Proclamation of Reward". The Arizona Sentinel. Yuma, Arizona Territory. June 1, 1889. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 122.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 123.

- Ball 1999, p. 176.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 122–123.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 123–124.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 106.

- Upton & Ball 1997, pp. 106–107.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 124.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 109.

- "The Wham Robbery". Arizona Weekly Citizen. Tucson, Arizona Territory. September 28, 1889. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2014-04-29. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- "The Wham Robbers". Sacramento Daily Record-Union. September 29, 1889. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 266.

- "Jury and Judges". Arizona Silver Belt. Globe City, Arizona Territory. October 5, 1889. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- McClintock 1916, p. 472.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 125.

- Wagoner 1970, p. 315.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 126.

- Fazio 1970, p. 31.

- "The Wham Robbers". Los Angeles Daily Herald. November 16, 1889. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Ball 1999, p. 178.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 128.

- Fazio 1970, p. 32.

- Fazio 1970, pp. 31–32.

- "All Acquitted". Sacramento Daily Record-Union. December 16, 1889. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2014-04-29. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 127.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 130.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 129.

- Ball 1999, p. 179.

- "Merit Rewarded". Arizona Weekly Citizen. Tucson, Arizona Territory. July 18, 1891. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- Upton & Ball 1997, p. 131.

Sources

- Ball, Larry D. (1999) [1978]. The United States Marshals of New Mexico and Arizona Territories, 1846–1912. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826306179. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- Fazio, Steven A. (Spring 1970). "Marcus Aurelius Smith: Arizona Delegate and Senator". Arizona and the West. 12 (1): 23–62. JSTOR 40168029.

- McClintock, James H. (1916). Arizona: Prehistoric – Aboriginal – Pioneer – Modern. Vol. II. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. OCLC 5398889. Archived from the original on 2014-07-05. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- Upton, Larry T.; Ball, Larry D. (Summer 1997). "Who Robbed Major Wham? Facts and Folklore behind Arizona's Great Paymaster Robbery". The Journal of Arizona History. Arizona Historical Society. 38 (2): 99–134. JSTOR 41696339.

- Wagoner, Jay J. (1970). Arizona Territory 1863–1912: A Political history. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816501769.

Further reading

- Ball, Larry D. (2000). Ambush at Bloody Run : The Wham Paymaster Robbery of 1889 : A Story of Politics, Religion, Race, and Banditry in Arizona Territory. Tucson: Arizona Historical Society. ISBN 978-0910037419.

- Marshall, Otto Miller (1967). The Wham Paymaster Pobbery. Pima, Arizona: Pima Chamber of Commerce. OCLC 1847453.

_troops_return_colors_to_Union_League_Club._Men_draw_._._._-_NARA_-_533590.jpg.webp)