Wilderness

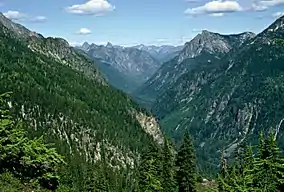

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural) are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity, or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation.[1][2] The term has traditionally referred to terrestrial environments, though growing attention is being placed on marine wilderness. Recent maps of wilderness[3] suggest it covers roughly one-quarter of Earth's terrestrial surface, but is being rapidly degraded by human activity.[4] Even less wilderness remains in the ocean, with only 13.2% free from intense human activity.[5]

Some governments establish protection for wilderness areas by law to not only preserve what already exists, but also to promote and advance a natural expression and development. These can be set up in preserves, conservation preserves, national forests, national parks and even in urban areas along rivers, gulches or otherwise undeveloped areas. Often these areas are considered important for the survival of certain species, biodiversity, ecological studies, conservation, solitude and recreation.[6] They may also preserve historic genetic traits and provide habitat for wild flora and fauna that may be difficult to recreate in zoos, arboretums or laboratories.

History

Ancient times and Middle Ages

From a visual arts perspective, nature and wildness have been important subjects in various epochs of world history. An early tradition of landscape art occurred in the Tang Dynasty (618–907). The tradition of representing nature as it is became one of the aims of Chinese painting and was a significant influence in Asian art. Artists in the tradition of Shan shui (lit. mountain-water-picture), learned to depict mountains and rivers "from the perspective of nature as a whole and on the basis of their understanding of the laws of nature … as if seen through the eyes of a bird". In the 13th century, Shih Erh Chi recommended avoiding painting "scenes lacking any places made inaccessible by nature".[7]

For most of human history, the greater part of Earth's terrain was wilderness, and human attention was concentrated on settled areas. The first known laws to protect parts of nature date back to the Babylonian Empire and Chinese Empire. Ashoka, the Great Mauryan King, defined the first laws in the world to protect flora and fauna in Edicts of Ashoka around the 3rd century B.C. In the Middle Ages, the Kings of England initiated one of the world's first conscious efforts to protect natural areas. They were motivated by a desire to be able to hunt wild animals in private hunting preserves rather than a desire to protect wilderness. Nevertheless, in order to have animals to hunt they would have to protect wildlife from subsistence hunting and the land from villagers gathering firewood.[8] Similar measures were introduced in other European countries.

However, in European cultures, throughout the Middle Ages, wilderness generally was not regarded worth protecting but rather judged strongly negative as a dangerous place and as a moral counter-world to the realm of culture and godly life.[9] "While archaic nature religions oriented themselves towards nature, in medieval Christendom this orientation was replaced by one towards divine law. The divine was no longer to be found in nature; instead, uncultivated nature became a site of the sinister and the demonic. It was considered corrupted by the Fall (natura lapsa), becoming a vale of tears in which humans were doomed to live out their existence. Thus, for example, mountains were interpreted [e.g, by Thomas Burnet[10]] as ruins of a once flat earth destroyed by the Flood, with the seas as the remains of that Flood."[9] "If paradise was early man's greatest good, wilderness, as its antipode, was his greatest evil."[11]

15th to 19th century

Wilderness was viewed by colonists as being evil in its resistance to their control.[12][13] The puritanical view of wilderness meant that in order for colonists to be able to live in North America, they had to destroy the wilderness in order to make way for their 'civilized' society.[12][13] Wilderness was considered to be the root of the colonists' problems, so to make the problems go away, wilderness needed to be destroyed.[12] One of the first steps in doing this, is to get rid of trees in order to clear the land.[12] Military metaphors describing the wilderness as the "enemy" were used, and settler expansion was phrased as "[conquering] the wilderness".[12]

In relation to the wilderness, Native Americans were viewed as savages.[14] The relationship between Native Americans and the land was something colonists did not understand and did not try to understand.[15] This mutually beneficial relationship was different from how colonists viewed the land only in relation to how it could benefit themselves by waging a constant battle to beat the land and other living organisms into submission.[12] The belief colonists had of the land being only something to be used was based in Christian ideas.[12] If the earth and animals and plants were created by a Christian God for human use, then the cultivation by colonists was their God-given goal.[14]

However, the idea that what European colonists saw upon arriving in North America was pristine and devoid of humans is untrue due to the existence of Native Americans.[16] The land was shaped by Native Americans through practices such as fires.[17] Burning happened frequently and in a controlled manner.[16] The landscapes seen in the US today are very different from the way things looked before colonists came.[16] Fire could be used to maintain food, cords, and baskets.[16] One of the main roles of frequent fires was to prevent the out of control fires which are becoming more and more common.[16]

The idea of wilderness having intrinsic value emerged in the Western world in the 19th century. British artists John Constable and J. M. W. Turner turned their attention to capturing the beauty of the natural world in their paintings. Prior to that, paintings had been primarily of religious scenes or of human beings. William Wordsworth's poetry described the wonder of the natural world, which had formerly been viewed as a threatening place. Increasingly the valuing of nature became an aspect of Western culture.[8]

By the mid-19th century, in Germany, "Scientific Conservation", as it was called, advocated "the efficient utilization of natural resources through the application of science and technology". Concepts of forest management based on the German approach were applied in other parts of the world, but with varying degrees of success.[18] Over the course of the 19th century wilderness became viewed not as a place to fear but a place to enjoy and protect; hence came the conservation movement in the latter half of the 19th century. Rivers were rafted and mountains were climbed solely for the sake of recreation, not to determine their geographical context.

In 1861, following an intense lobbying by artists (painters), the French Waters and Forests Military Agency set an "artistic reserve" in Fontainebleau State Forest. With a total of 1,097 hectares, it is known to be the first World nature reserve.

Modern conservation

Global conservation became an issue at the time of the dissolution of the British Empire in Africa in the late 1940s. The British established great wildlife preserves there. As before, this interest in conservation had an economic motive: in this case, big game hunting. Nevertheless, this led to growing recognition in the 1950s and the early 1960s of the need to protect large spaces for wildlife conservation worldwide. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), founded in 1961, grew to be one of the largest conservation organizations in the world.[8]

Early conservationists advocated the creation of a legal mechanism by which boundaries could be set on human activities in order to preserve natural and unique lands for the enjoyment and use of future generations. This profound shift in wilderness thought reached a pinnacle in the US with the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, which allowed for parts of U.S. National Forests to be designated as "wilderness preserves". Similar acts, such as the 1975 Eastern Wilderness Areas Act, followed.

Nevertheless, initiatives for wilderness conservation continue to increase. There are a growing number of projects to protect tropical rainforests through conservation initiatives. There are also large-scale projects to conserve wilderness regions, such as Canada's Boreal Forest Conservation Framework. The Framework calls for conservation of 50 percent of the 6,000,000 square kilometres of boreal forest in Canada's north.[19] In addition to the World Wildlife Fund, organizations such as the Wildlife Conservation Society, the WILD Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, The Wilderness Society (United States) and many others are active in such conservation efforts.

The 21st century has seen another slight shift in wilderness thought and theory. It is now understood that simply drawing lines around a piece of land and declaring it a wilderness does not necessarily make it a wilderness. All landscapes are intricately connected and what happens outside a wilderness certainly affects what happens inside it. For example, air pollution from Los Angeles and the California Central Valley affects Kern Canyon and Sequoia National Park. The national park has miles of "wilderness" but the air is filled with pollution from the valley. This gives rise to the paradox of what a wilderness really is; a key issue in 21st century wilderness thought.

National parks

The creation of national parks, beginning in the 19th century, preserved some especially attractive and notable areas, but the pursuits of commerce, lifestyle, and recreation combined with increases in human population have continued to result in human modification of relatively untouched areas. Such human activity often negatively impacts native flora and fauna. As such, to better protect critical habitats and preserve low-impact recreational opportunities, legal concepts of "wilderness" were established in many countries, beginning with the United States (see below).

The first National Park was Yellowstone, which was signed into law by U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant on 1 March 1872.[20] The Act of Dedication declared Yellowstone a land "hereby reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States, and dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."[21]

When national parks were established in an area, the Native Americans that had been living there were forcibly removed so visitors to the park could see nature without humans present.[22] National parks are seen as areas untouched by humans, when in reality, humans existed in these spaces, until settler colonists came in and forced them off their lands in order to create the national parks.[22] The concept glorifies the idea that before settlers came, the US was an uninhabited landscape.[22] This erases the reality of Native Americans, and their relationship with the land and the role they had in shaping the landscape.[22] Such erasure suggests there were areas of the US which were historically unoccupied, once again erasing the existence of Native Americans and their relationship to the land.[22] In the case of Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and Yosemite, the 'preservation' of these lands by the US government was what caused the Native Americans who lived in the areas to be systematically removed.[22]

Historian Mark David Spence has shown that the case of Glacier National Park and the Blackfeet people who live there is a perfect example of such erasure.[22] The Blackfeet people had specifically designated rights to the area, but the 1910 Glacier National Park act made void those rights.[22][17] The act of 'preserving' the land was specifically linked to the exclusion of the Blackfeet people.[22] The continued resistance of the Blackfeet people has provided documentation of the importance of the area to many different tribes.[17][22]

The world's second national park, the Royal National Park, located just 32 km to the south of Sydney, Australia, was established in 1879.[23]

The U.S. concept of national parks soon caught on in Canada, which created Banff National Park in 1885, at the same time as the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway was being built. The creation of this and other parks showed a growing appreciation of wild nature, but also an economic reality. The railways wanted to entice people to travel west. Parks such as Banff and Yellowstone gained favor as the railroads advertised travel to "the great wild spaces" of North America. When outdoorsman Teddy Roosevelt became president of the United States, he began to enlarge the U.S. National Parks system, and established the National Forest system.[8]

By the 1920s, travel across North America by train to experience the "wilderness" (often viewing it only through windows) had become very popular. This led to the commercialization of some of Canada's National Parks with the building of great hotels such as the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise.

Despite their similar name, national parks in England and Wales are quite different from national parks in many other countries. Unlike most other countries, in England and Wales, designation as a national park may include substantial settlements and human land uses which are often integral parts of the landscape, and land within a national park remains largely in private ownership. Each park is operated by its own national park authority.

The United States philosophy around wilderness preservation through National Parks has been attempted in other countries.[24] However, people living in those countries have different ideas surrounding wilderness than people in the United States, thus, the US concept of wilderness can be damaging in other areas of the world.[24] India is more densely populated and has been settled for a long time.[24] There are complex relationships between agricultural communities and the wilderness.[24] An example of this is the Project Tiger parks in India.[24] By claiming areas as no longer used by humans, the land moves from the hands of poor people to rich people.[24] Having designated tiger reserves is only possible by displacing poor people, who were not involved in the planning of the areas.[24] This situation places the ideal of wilderness above the already existing relationships between people and the land they live on.[24] By placing an imperialistic ideal of nature onto a different country, the desire to reestablish wilderness is being put above the lives of those who live by working the land.[24]

Conservation and preservation in 20th century United States

By the late 19th century, it had become clear that in many countries wild areas had either disappeared or were in danger of disappearing. This realization gave rise to the conservation movement in the United States, partly through the efforts of writers and activists such as John Burroughs, Aldo Leopold, and John Muir, and politicians such as U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt.

The idea of protecting nature for nature's sake began to gain more recognition in the 1930s with American writers like Aldo Leopold, calling for a "land ethic" and urging wilderness protection. It had become increasingly clear that wild spaces were disappearing rapidly and that decisive action was needed to save them. Wilderness preservation is central to deep ecology; a philosophy that believes in an inherent worth of all living beings, regardless of their instrumental utility to human needs.[25]

Two different groups had emerged within the US environmental movement by the early 20th century: the conservationists and the preservationists. The initial consensus among conservationists was split into "utilitarian conservationists" later to be referred to as conservationists, and "aesthetic conservationists" or preservationists. The main representative for the former was Gifford Pinchot, first Chief of the United States Forest Service, and they focused on the proper use of nature, whereas the preservationists sought the protection of nature from use.[18] Put another way, conservation sought to regulate human use while preservation sought to eliminate human impact altogether. The management of US public lands during the years 1960s and 70s reflected these dual visions, with conservationists dominating the Forest Service, and preservationists the Park Service[26]

Formal wilderness designations

International

The World Conservation Union (IUCN) classifies wilderness at two levels, 1a (strict nature reserves) and 1b (Wilderness areas).[27]

There have been recent calls for the World Heritage Convention to better protect wilderness[28] and to include the word wilderness in their selection criteria for Natural Heritage Sites

Forty-eight countries have wilderness areas established via legislative designation as IUCN protected area management Category 1b sites that do not overlap with any other IUCN designation. They are: Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Canada, Cayman Islands, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Czech Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Estonia, Finland, French Guiana, Greenland, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Marshall Islands, Mexico, Mongolia, Nepal, New Zealand, Norway, Northern Mariana Islands, Portugal, Seychelles, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Tanzania, United States of America, and Zimbabwe. At publication, there are 2,992 marine and terrestrial wilderness areas registered with the IUCN as solely Category 1b sites.[29]

Twenty-two other countries have wilderness areas. These wilderness areas are established via administrative designation or wilderness zones within protected areas. Whereas the above listing contains countries with wilderness exclusively designated as Category 1b sites, some of the below-listed countries contain protected areas with multiple management categories including Category 1b. They are: Argentina, Bhutan, Brazil, Chile, Honduras, Germany, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, Namibia, Nepal, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Philippines, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Switzerland, Uganda, Ukraine, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Venezuela, and Zambia.[29]

Germany

The German National Strategy on Biological Diversity aims to establish wilderness areas on 2% of its terrestrial territory by 2020 (7,140 km2). However, protected wilderness areas in Germany currently only cover 0.6% of the total terrestrial area. In absence of pristine landscapes, Germany counts national parks (IUCN Category II) as wilderness areas.[30] The government counts the whole area of the 16 national parks as wilderness. This means, also the managed parts are included in the "existing" 0,6%. There is no doubt, that Germany will miss its own time-dependent quantitative goals, but there are also some critics, that point a bad designation practice: Findings of disturbance ecology, according to which process-based nature conservation and the 2% target could be further qualified by more targeted area designation, pre-treatment and introduction of megaherbivores, are widely neglected.[31] Since 2019 the government supports bargains of land that will then be designated as wilderness by 10 Mio. Euro annually.[32] The German minimum size for wilderness candidate sites is normally 10 km2. In some cases (i.e. swamps) the minimum size is 5 km2.[33]

Finland

There are twelve wilderness areas in the Sami native region in northern Finnish Lapland. They are intended both to preserve the wilderness character of the areas and further the traditional livelihood of the Sami people. This means e.g. that reindeer husbandry, hunting and taking wood for use in the household is permitted. As population is very sparse, this is generally no big threat to the nature. Large scale reindeer husbandry has influence on the ecosystem, but no change is introduced by the act on wilderness areas. The World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) classifies the areas as "VI Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources".

France

Since 1861, the French Waters and Forests Military Agency (Administration des Eaux et Forêts) put a strong protection on what was called the « artistic reserve » in Fontainebleau State Forest. With a total of 1,097 hectares, it is known to be the first World nature reserve.

Then in the 1950s,[34] Integral Biological Reserves (Réserves Biologiques Intégrales, RBI) are dedicated to man free ecosystem evolution, on the contrary of Managed Biological reserves (Réserves Biologiques Dirigées, RBD) where a specific management is applied to conserve vulnerable species or threatened habitats.

Integral Biological Reserves occurs in French State Forests or City Forests and are therefore managed by the National Forests Office. In such reserves, all harvests coupe are forbidden excepted exotic species elimination or track safety works to avoid fallen tree risk to visitors (already existing tracks in or on the edge of the reserve).

At the end of 2014,[35] there were 60 Integral Biological Reserves in French State Forests for a total area of 111,082 hectares and 10 in City Forests for a total of 2,835 hectares.

Greece

In Greece there are some parks called "ethniki drimoi" (εθνικοί δρυμοί, national forests) that are under protection of the Greek government. Such parks include Olympus, Parnassos and Parnitha National Parks.

New Zealand

There are seven Wilderness Areas in New Zealand as defined by the National Parks Act 1980 and the Conservation Act 1987 that fall well within the IUCN definition. Wilderness areas cannot have any human intervention and can only have indigenous species re-introduced into the area if it is compatible with conservation management strategies.

In New Zealand wilderness areas are remote blocks of land that have high natural character.[36] The Conservation Act 1987 prevents any access by vehicles and livestock, the construction of tracks and buildings, and all indigenous natural resources are protected.[37] They are generally over 400 km2 in size.[38]

Three Wilderness Areas are currently recognised, all on the West Coast: Adams Wilderness Area, Hooker/Landsborough Wilderness Area and Paparoa Wilderness Area.[39]

United States

In the United States, a Wilderness Area is an area of federal land set aside by an act of Congress. It is typically at least 5,000 acres (about 8 mi2 or 20 km2) in size.[40] Human activities in wilderness areas are restricted to scientific study and non-mechanized recreation; horses are permitted but mechanized vehicles and equipment, such as cars and bicycles, are not.

The United States was one of the first countries to officially designate land as "wilderness" through the Wilderness Act of 1964. The Wilderness Act is an important part of wilderness designation because it created the legal definition of wilderness and established the National Wilderness Preservation System. The Wilderness Act defines wilderness as "an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain."[41]

Wilderness designation helps preserve the natural state of the land and protects flora and fauna by prohibiting development and providing for non-mechanized recreation only.

The first administratively protected wilderness area in the United States was the Gila National Forest. In 1922, Aldo Leopold, then a ranking member of the U.S. Forest Service, proposed a new management strategy for the Gila National Forest. His proposal was adopted in 1924, and 750,000 acres of the Gila National Forest became the Gila Wilderness.[42]

The Great Swamp in New Jersey was the first formally designated wilderness refuge in the United States. It was declared a wildlife refuge on 3 November 1960. In 1966 it was declared a National Natural Landmark and, in 1968, it was given wilderness status. Properties in the swamp had been acquired by a small group of residents of the area, who donated the assembled properties to the federal government as a park for perpetual protection. Today the refuge amounts to 7,600 acres (31 km2) that are within thirty miles of Manhattan.[43]

While wilderness designations were originally granted by an Act of Congress for Federal land that retained a "primeval character", meaning that it had not suffered from human habitation or development, the Eastern Wilderness Act of 1975 extended the protection of the NWPS to areas in the eastern states that were not initially considered for inclusion in the Wilderness Act. This act allowed lands that did not meet the constraints of size, roadlessness, or human impact to be designated as wilderness areas under the belief that they could be returned to a "primeval" state through preservation.[44]

Approximately 107,500,000 acres (435,000 km2) are designated as wilderness in the United States. This accounts for 4.82% of the country's total land area; however, 54% of that amount is found in Alaska (recreation and development in Alaskan wilderness is often less restrictive), while only 2.58% of the lower continental United States is designated as wilderness. As of 2023 there are 806 designated wilderness areas in the United States ranging in size from Florida's Pelican Island at 5 acres (20,000 m2) to Alaska's Wrangell-Saint Elias at 9,078,675 acres (36,740.09 km2).

Western Australia

In Western Australia,[45] a wilderness area is an area that has a wilderness quality rating of 12 or greater and meets a minimum size threshold of 80 km2 in temperate areas or 200 km2 in arid and tropical areas. A wilderness area is gazetted under section 62(1)(a) of the Conservation and Land Management Act 1984 by the Minister on any land that is vested in the Conservation Commission of Western Australia.

International movement

At the forefront of the international wilderness movement has been The WILD Foundation, its founder Ian Player and its network of sister and partner organizations around the globe. The pioneer World Wilderness Congress in 1977 introduced the wilderness concept as an issue of international importance, and began the process of defining the term in biological and social contexts. Today, this work is continued by many international groups who still look to the World Wilderness Congress as the international venue for wilderness and to The WILD Foundation network for wilderness tools and action. The WILD Foundation also publishes the standard references for wilderness professionals and others involved in the issues: Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values, the International Journal of Wilderness, A Handbook on International Wilderness Law and Policy and Protecting Wild Nature on Native Lands are the backbone of information and management tools for international wilderness issues.

The Wilderness Specialist Group within the World Commission on Protected Areas (WTF/WCPA) of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) plays a critical role in defining legal and management guidelines for wilderness at the international level and is also a clearing-house for information on wilderness issues.[46] The IUCN Protected Areas Classification System defines wilderness as "A large area of unmodified or slightly modified land, and/or sea retaining its natural character and influence, without permanent or significant habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural condition (Category 1b)." The WILD Foundation founded the WTF/WCPA in 2002 and remains co-chair.

Extent

The most recent efforts to map wilderness[47] show that less than one quarter (~23%) of the world's wilderness area now remains, and that there have been catastrophic declines in wilderness[48] extent over the last two decades. Over 3 million square kilometers (10 percent) of wilderness was converted to human land-uses. The Amazon and Congo rain forests suffered the most loss. Human pressure is extending into almost every corner of the planet.[49] The loss of wilderness could have serious implications for biodiversity conservation.

According to a previous study, Wilderness: Earth's Last Wild Places, carried out by Conservation International, 46% of the world's land mass is wilderness. For purposes of this report, "wilderness" was defined as an area that "has 70% or more of its original vegetation intact, covers at least 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 sq mi) and must have fewer than five people per square kilometer."[50] However, an IUCN/UNEP report published in 2003, found that only 10.9% of the world's land mass is currently a Category 1 Protected Area, that is, either a strict nature reserve (5.5%) or protected wilderness (5.4%).[51] Such areas remain relatively untouched by humans. Of course, there are large tracts of lands in national parks and other protected areas that would also qualify as wilderness. However, many protected areas have some degree of human modification or activity, so a definitive estimate of true wilderness is difficult.

The Wildlife Conservation Society generated a human footprint using a number of indicators, the absence of which indicate wildness: human population density, human access via roads and rivers, human infrastructure for agriculture and settlements and the presence of industrial power (lights visible from space). The society estimates that 26% of the Earth's land mass falls into the category of "Last of the wild." The wildest regions of the world include the Arctic Tundra, the Siberia Taiga, the Amazon rainforest, the Tibetan Plateau, the Australia Outback and deserts such as the Sahara, and the Gobi.[52] However, from the 1970s, numerous geoglyphs have been discovered on deforested land in the Amazon rainforest, leading to claims about Pre-Columbian civilizations.[53][54] The BBC's Unnatural Histories claimed that the Amazon rainforest, rather than being a pristine wilderness, has been shaped by man for at least 11,000 years through practices such as forest gardening and terra preta.[55]

The percentage of land area designated wilderness does not necessarily reflect a measure of its biodiversity. Of the last natural wilderness areas, the taiga—which is mostly wilderness—represents 11% of the total land mass in the Northern Hemisphere.[56] Tropical rainforest represent a further 7% of the world's land base.[57] Estimates of the Earth's remaining wilderness underscore the rate at which these lands are being developed, with dramatic declines in biodiversity as a consequence.

Critique

The American concept of wilderness has been criticized by some nature writers. For example, William Cronon writes that what he calls a wilderness ethic or cult may "teach us to be dismissive or even contemptuous of such humble places and experiences", and that "wilderness tends to privilege some parts of nature at the expense of others", using as an example "the mighty canyon more inspiring than the humble marsh."[58] This is most clearly visible with the fact that nearly all U.S. National Parks preserve spectacular canyons and mountains, and it was not until the 1940s that a swamp became a national park—the Everglades. In the mid-20th century national parks started to protect biodiversity, not simply attractive scenery.

Cronon also believes the passion to save wilderness "poses a serious threat to responsible environmentalism" and writes that it allows people to "give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead ... to the extent that we live in an urban-industrial civilization but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness".[58]

Michael Pollan has argued that the wilderness ethic leads people to dismiss areas whose wildness is less than absolute. In his book Second Nature, Pollan writes that "once a landscape is no longer 'virgin' it is typically written off as fallen, lost to nature, irredeemable."[59] Another challenge to the conventional notion of wilderness comes from Robert Winkler in his book, Going Wild: Adventures with Birds in the Suburban Wilderness. "On walks in the unpeopled parts of the suburbs," Winkler writes, "I’ve witnessed the same wild creatures, struggles for survival, and natural beauty that we associate with true wilderness."[60] Attempts have been made, as in the Pennsylvania Scenic Rivers Act, to distinguish "wild" from various levels of human influence: in the Act, "wild rivers" are "not impounded", "usually not accessible except by trail", and their watersheds and shorelines are "essentially primitive".[61]

Another source of criticism is that the criteria for wilderness designation is vague and open to interpretation. For example, the Wilderness Act states that wilderness must be roadless. The definition given for roadless is "the absences of roads which have been improved and maintained by mechanical means to insure relatively regular and continuous use".[62] However, there have been added sub-definitions that have, in essence, made this standard unclear and open to interpretation, and some are drawn to narrowly exclude existing roads.

Coming from a different direction, some criticism from the Deep Ecology movement argues against conflating "wilderness" with "wilderness reservations", viewing the latter term as an oxymoron that, by allowing the law as a human construct to define nature, unavoidably voids the very freedom and independence of human control that defines wilderness.[63] True wilderness requires the ability of life to undergo speciation with as little interference from humanity as possible.[64] Anthropologist and scholar on wilderness Layla Abdel-Rahim argues that it is necessary to understand the principles that govern the economies of mutual aid and diversification in wilderness from a non-anthropocentric perspective.[65]

Others have criticized the American concept of wilderness as rooted in white supremacy, ignoring Native American perspectives on the natural environment and excluding people of color from narratives about human interactions with the environment. Many early conservationists, such as Madison Grant, were also heavily involved in the eugenics movement. Grant, who worked alongside President Theodore Roosevelt to create the Bronx Zoo, also wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a book on eugenics that was later praised by Adolf Hitler. Grant is also known to have featured Ota Benga, a Mbuti man from Central Africa, in the Bronx Zoo monkey house exhibit.[66] John Muir, another important figure in the early conservation movement, referred to African-Americans as "making a great deal of noise and doing little work", and compared Native Americans to unclean animals who did not belong in the wilderness.[67] Environmental history professor Miles A. Powell of Nanyang Technological University has argued that much of the early conservation movement was deeply tied to and inspired by a desire to preserve the Nordic race.[68] Prakash Kashwan, a political science professor at the University of Connecticut who specializes in environmental policies and environmental justice, argues that the racist ideas of many early conservationists created a narrative of wilderness that has led to "fortress conservation" policies that have driven Native Americans off of their land. Kashwan has proposed conservation practices that would allow Indigenous people to continue using the land as a more just and more effective alternative to fortress conservation.[69] The idea that the natural world is primarily made up of remote wilderness areas has also been criticized as classist, with environmental sociologist Dorceta Taylor arguing that this leads to experiencing wilderness becoming a privilege, as working-class people are often unable to afford transportation to wilderness areas. She further argues that, due to poverty and lack of access to transportation caused by systemic racism, this perception is also rooted in racism.[70]

Human–nature dichotomy

Another critique of wilderness is that it perpetuates the human-nature dichotomy. The idea that nature and humans are separate entities can be traced back to European colonial views. To European settlers, land was an inherited right and was to be used to profit.[71] While native groups saw their relationship with the land in a more holistic view, they were eventually subjected to European property systems.[72] Colonists from Europe saw the American landscape as wild, savage, dark, [etc.] and thus needed to be tamed in order for it to be safe and habitable. Once cleared and settled, these areas were depicted as "Eden itself".[73] Yet the native peoples of those lands saw "wilderness" as that when the connection between humans and nature is broken.[74] For native communities, human intervention was a part of their ecological practices.

There is a historical belief that wilderness must not only be tamed to be protected but that humans also need to be outside of it.[75] In order to clear certain areas for conservation, such as national parks, involved the removal of native communities from their land.[73] Some authors have come to describe this type of conservation as conservation-far, where humans and nature are kept separate. The other end of the conservation spectrum then, would be conservation-near, which would mimic native ecological practices of humans integrated into the care of nature.[75]

Most scientists and conservationists agree that no place on earth is completely untouched by humanity, either due to past occupation by indigenous people, or through global processes such as climate change or pollution. Activities on the margins of specific wilderness areas, such as fire suppression and the interruption of animal migration, also affect the interior of wildernesses.

See also

- Aldo Leopold

- Adventure travel

- Biomass

- Biomass (ecology)

- Bioproduct

- Camping

- Conservation movement

- Deforestation

- Ecological footprint

- Environmental education

- Forest

- Geology

- Global warming

- Hiking

- Intact forest landscape

- John Muir Lifetime Achievement Award

- Land use

- Last of the Wild

- Leave no trace

- List of U.S. Wilderness Areas

- List of conservationists

- Bob Marshall

- National Outdoor Leadership School

- National Wilderness Preservation System

- National Wildlife Magazine

- Native American use of fire

- Natural landscape

- Old-growth forest

- Outdoor education

- Permaforestry

- Planetary habitability

- Protected area

- Wild fisheries

- Wildcrafting

- Wilderness Act (1964)

- Wilderness therapy

- Wilderness Area (Protected Area Management Category)

- Terra nullius – International law term for unclaimed land

References

- "Glossary". National Weather Service.

- "What is a Wilderness Area". WILD Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Allan, James R.; Venter, Oscar; Watson, James E. M. (12 December 2017). "Temporally inter-comparable maps of terrestrial wilderness and the Last of the Wild". Scientific Data. 4 (1): 170187. Bibcode:2017NatSD...470187A. doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.187. PMC 5726312. PMID 29231923.

- Watson, James E.M.; Shanahan, Danielle F.; Di Marco, Moreno; Allan, James; Laurance, William F.; Sanderson, Eric W.; Mackey, Brendan; Venter, Oscar (November 2016). "Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets". Current Biology. 26 (21): 2929–2934. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.049. PMID 27618267.

- Jones, Kendall R.; Klein, Carissa J.; Halpern, Benjamin S.; Venter, Oscar; Grantham, Hedley; Kuempel, Caitlin D.; Shumway, Nicole; Friedlander, Alan M.; Possingham, Hugh P.; Watson, James E. M. (August 2018). "The Location and Protection Status of Earth's Diminishing Marine Wilderness". Current Biology. 28 (15): 2506–2512.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.010. PMID 30057308.

- Botkin, Daniel B. No Man's Garden. pp. 155–157.

- Chinese brush painting Archived 26 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine Asia-art.net Retrieved on: 20 May 2006.

- History of Conservation BC Spaces for Nature. Retrieved: 20 May 2006.

- Kirchhoff, Thomas/ Vicenzotti, Vera 2014: A historical and systematic survey of European perceptions of wilderness. Environmental Values 23 (4): pp.443–464, here p. 446, doi:(10.3197/096327114X13947900181590

- Burnet, Thomas [1681 ]1719: The Sacred Theory of the Earth. Containing an Account of the Original of the Earth and of all the General Changes which it hath Already Undergone, or is to Undergo, till the Consumation of all Things. The Forth Edition. London, Hooke. https://archive.org/details/sacredtheoryofea01burn.

- Nash, Roderick Frazier [1967] 2014: Wilderness and the American Mind. Fifth Edition. New Haven & London, Yale University Press / Yale Nota Bene, p. 9

- Roderick, Nash (1973). Wilderness and the American mind. Yale University Press. OCLC 873974940.

- Hogan, L. (1994). Department of the Interior. In P. Foster (Ed.), Minding the Body.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Beacon Press

- "Land as Pedagogy". As We Have Always Done. 2017. pp. 145–174. doi:10.5749/j.ctt1pwt77c.12. ISBN 9781452956008.

- Stewart, O. C., Lewis, H. T., & Anderson, K. (2002). Forgotten fires: Native Americans and the transient wilderness. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Kantor, I. (2007). Ethnic Cleansing and America's Creation of National Parks. Public Land & Resources Law Review, 28, 41-64.

- Akamani, K. (nd). "The Wilderness Idea: A Critical Review." Archived 30 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine A Better Earth.org. Retrieved: 1 June 2006

- Canadian Boreal Initiative Boreal Forest Conservation Framework Archived 8 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. www.borealcanada.ca Retrieved on: 1 December 2007.

- Mangan, E. Yellowstone, the First National Park Library of Congress, Mapping the National Parks. Retrieved on: 2010-08-12.

- "The Magic of Yellowstone". Congressional Acts Pertaining to Yellowstone. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Spence, Mark David (July 1996). "Crown of the Continent, Backbone of the World: The American Wilderness Ideal and Blackfeet Exclusion from Glacier National Park". Environmental History. 1 (3): 29–49. doi:10.2307/3985155. JSTOR 3985155. S2CID 143232340.

- New South Wales National Parks & Wildlife Service, "Parks & Reserves: Royal National Park" Archived 20 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 6 December 2011.

- Guha, Ramachandra. ""Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Preservation: A Third World Critique" (1997)." The Future of Nature. New Haven: Yale UP, 2017. 409-32. Web.

- John Barry; E. Gene Frankland (2002). International Encyclopedia of Environmental Politics. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 9780415202855.

- Young, Raymond A. (1982). Introduction to Forest Science. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-471-06438--1.

- Locke, H.; Ghosh, S.; Carver, S.; McDonald, T.; Sloan, S.S.; Merculieff, I.; Hendee, J.; Dawson, C.; Moore, S.; Newsome, D.; McCool, S.; Semler, R.; Martin, S.; Dvorak, R.; Armatas, C.; Swain, R.; Barr, B.; Krause, D.; Whittington-Evans, N.; Hamilton, L.S.; Holtrop, J.; Tricker, J.; Landres, P.; Mejicano, E.; Gilbert, T.; MacKey, B.; Aykroyd, T.; Zimmerman, B.; Thomas, J. (2016). Wilderness protected areas: Management guidelines for IUCN category 1b protected areas. doi:10.2305/IUCN.CH.2016.PAG.25.en. ISBN 9782831718170.

- Allan, James R.; Kormos, Cyril; Jaeger, Tilman; Venter, Oscar; Bertzky, Bastian; Shi, Yichuan; Mackey, Brendan; van Merm, Remco; Osipova, Elena; Watson, James E.M. (February 2018). "Gaps and opportunities for the World Heritage Convention to contribute to global wilderness conservation". Conservation Biology. 32 (1): 116–126. doi:10.1111/cobi.12976. PMID 28664996. S2CID 28944427.

- "The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA)". IUCN and UNEP-WCMC. 2016.

- Brackhane, Sebastian; Schoof, Nicolas; Reif, Albert; Schmitt, Christine B. (2019). "A new wilderness for Central Europe? – the potential for large strictly protected forest reserves in Germany". Biological Conservation. 237: 373–382. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.06.026. S2CID 199641237.

- Schoof, Nicolas; Luick, Rainer; Nickel, Herbert; Reif, Albert; Förschler, Marc; Westrich, Paul; Reisinger, Edgar (2018). "Biodiversität fördern mit Wilden Weiden in der Vision "Wildnisgebiete" der Nationalen Strategie zur biologischen Vielfalt". Natur und Landschaft. 93 (7): 314–322.

- "Deutschland wird wilder: Neues Förderinstrument Wildnisfonds startet – BMU-Pressemitteilung". bmu.de (in German). Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Opitz, Stefaie; Reppin, Nicole; Schoof, Nicolas; Drobnik, Juliane; Riecken, Uwe; Mengel, Andreas; Reif, Albert; Rosenthal, Gert; Finck, Peter (2015). "Wildnis in Deutschland: Nationale Ziele, Status Quo und Potenziale". Natur und Landschaft. 90: 406–412.

- 1995 & 1998 National Forests Office internal instructions in application of the last paragraph of article L. 212-2 of the French Forest Act

- "L'ONF". 30 October 2018.

- "Wilderness Areas". New Zealand Tramper. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- New Zealand Government (1987). "Conservation Act 1987 Part 4, Section 20". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- Molloy, Les. "Specially protected areas". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- "New Zealand Gazetteer". linz.govt.nz. Land Information New Zealand.

- United States National Park Service – Wilderness – Fort Pulaski National Monument https://www.nps.gov/fopu/learn/nature/wilderness.htm

- "Wilderness Act of 1964". Wilderness.net. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- "Aldo Leopold". Prominent Figures in Wilderness History. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. Retrieved on: 7 June 2008.

- "The Wilderness Act of 1964". Western North Carolina's Mountain Treasures. Retrieved on 16 June 2010.

- Department of Conservation and Land Management Policy Statement No 62, Identification and management of Wilderness and surrounding areas.

- "Wilderness". IUCN. 8 February 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Allan, James R.; Venter, Oscar; Watson, James E. M. (12 December 2017). "Temporally inter-comparable maps of terrestrial wilderness and the Last of the Wild". Scientific Data. 4 (1): 170187. Bibcode:2017NatSD...470187A. doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.187. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 5726312. PMID 29231923.

- Watson, James E. M.; Shanahan, Danielle F.; Di Marco, Moreno; Allan, James; Laurance, William F.; Sanderson, Eric W.; Mackey, Brendan; Venter, Oscar (7 November 2016). "Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets". Current Biology. 26 (21): 2929–2934. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.049. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 27618267.

- Venter, Oscar; Sanderson, Eric W.; Magrach, Ainhoa; Allan, James R.; Beher, Jutta; Jones, Kendall R.; Possingham, Hugh P.; Laurance, William F.; Wood, Peter; Fekete, Balázs M.; Levy, Marc A. (23 August 2016). "Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12558. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712558V. doi:10.1038/ncomms12558. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4996975. PMID 27552116.

- Conservation International (2002) Global Analysis Finds Nearly Half The Earth Is Still Wilderness. Retrieved on 6 Nov 2017.

- Chape, S., S. Blyth, L. Fish, P. Fox and M. Spalding (compilers) (2003). 2003 United Nations List of Protected Areas. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK and UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. PDF Archived 1 July 2004 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Wildlife Conservation Society. 2005. State of the Wild 2006: A Global Portrait of Wildlife, Wildlands and Oceans. Washington, D.C. Island Press. pp. 16 &17.

- Simon Romero (14 January 2012). "Once Hidden by Forest, Carvings in Land Attest to Amazon's Lost World". The New York Times.

- Martti Pärssinen; Denise Schaan & Alceu Ranzi (2009). "Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Purús: a complex society in western Amazonia". Antiquity. 83 (322): 1084–1095. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099373. S2CID 55741813.

- "Unnatural Histories – Amazon". BBC Four.

- University of Manitoba Taiga Biological Station. 2004. Frequently answered questions. Retrieved: 2006-07-04.

- Rainforest Foundation US. 2006. Commonly asked questions. Retrieved: 2006-07-04.

- The Trouble with Wilderness Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved: 28 January 2007.

- Pollan, Michael (2003). Second Nature: A Gardener's Education p. 188. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4011-1.

- Winkler, Robert. (2003). Going Wild: Adventures with Birds in the Suburban Wilderness National Geographic ISBN 978-0-7922-6168-1.

- Pennsylvania Scenic Rivers Act (P.L. 1277, Act No. 283 as amended by Act 110, May 7, 1982)

- Durrant, Jeffrey O. (2007). Struggle over Utah's San Rafael Swell: Wilderness, National Conservation Areas, and National Monuments. University of Arizona Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8165-2669-7.

- Thomas Birch (1995). George Sessions (ed.). Deep Ecology for the 21st Century. Boston: Shambhala. pp. 345, 339–355. ISBN 978-1-57062-049-2.

- George Sessions (1995). Deep Ecology for the 21st Century. Boston: Shambhala. pp. 323, 323–330. ISBN 978-1-57062-049-2.

- Layla AbdelRahim (2015). Children's Literature, Domestication, and Social Foundation: Narratives of Civilization and Wilderness. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66110-2.

- Jonathan Spiro (2009). Defending the Master Race : Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. Burlington: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-584-65715-6.

- "Shades of Darkness: Race and Environmental History". 11 April 2005. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Miles A. Powell (2016). Vanishing America : Species Extinction, Racial Peril, and the Origins of Conservation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97156-1.

- "American environmentalism's racist roots have shaped global thinking about conservation". 2 September 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Dorceta E. Taylor (2016). The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7397-1.

- Opello, Walter C.; Rosow, Stephen J. (2004). The nation-state and global order : a historical introduction to contemporary politics. Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-58826-289-8. OCLC 760384471.

- Park, K-Sue (2016). "Money, Mortgages, and the Conquest of America". Law & Social Inquiry. 41 (4): 1006–1035. doi:10.1111/lsi.12222. ISSN 0897-6546. S2CID 157705999.

- William., Cronon (1996). Uncommon ground : rethinking the human place in nature. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-31511-8. OCLC 36306399.

- Anderson, M. Kat (14 June 2005). Tending the Wild. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520933101. ISBN 978-0-520-93310-1.

- Claus, C. Anne (3 November 2020). Drawing the Sea Near. University of Minnesota Press. doi:10.5749/j.ctv1bkc3t6. ISBN 978-1-4529-5946-7. S2CID 230646912.

Further reading

- Bryson, B. (1998). A Walk in the Woods. ISBN 0-7679-0251-3

- Casson, S. et al. (Ed.s). (2016). Wilderness Protected Areas: Management Guidelines for IUCN Category 1b (wilderness) Protected Areas ISBN 978-2-8317-1817-0

- Gutkind, L (Ed). (2002). On Nature: Great Writers on the Great Outdoors. ISBN 1-58542-173-1

- Kirchhoff, Thomas/ Vicenzotti, Vera 2014: A historical and systematic survey of European perceptions of wilderness. Environmental Values 23 (4): 443–464.

- Nash, Roderick Frazier [1967] 2014: Wilderness and the American Mind. Fifth Edition. New Haven & London, Yale University Press / Yale Nota Bene.

- Oelschlaeger, Max 1991: The Idea of Wilderness. From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

Documentaries

- 2022: Wild Forests by David Cebulla

External links

- The Wilderness Society

- Wilderness Information Network

- Wilderness Articles, Survival Techniques, Edible Plants

- Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute

- Wilderness Task Force/World Commission on Protect Areas

- Campaign for America's Wilderness

- The WILD Foundation"American Wilderness Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Definitions

- Detailed maps of United States wilderness designations

- What is Wilderness? – Definition and discussion of wilderness as a human construction

- Wilderness and the American Mind – by Roderick Nash

- The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature by William Cronon.

.jpg.webp)