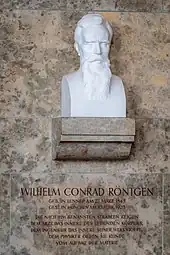

Wilhelm Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (/ˈrɛntɡən, -dʒən, ˈrʌnt-/;[3] German pronunciation: [ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈʁœntɡən] ⓘ; 27 March 1845 – 10 February 1923) was a German mechanical engineer and physicist,[4] who, on 8 November 1895, produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays or Röntgen rays, an achievement that earned him the inaugural Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901.[5][6] In honour of Röntgen's accomplishments, in 2004 the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) named element 111, roentgenium, a radioactive element with multiple unstable isotopes, after him. The unit of measurement roentgen was also named after him.

Wilhelm Röntgen | |

|---|---|

Röntgen in 1900 | |

| Born | Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen 27 March 1845 |

| Died | 10 February 1923 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | |

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Bertha Röntgen (deceased 1919)[2] |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | August Kundt |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students | Franz S. Exner |

| Signature | |

Biographical history

Education

He was born to Friedrich Conrad Röntgen, a German merchant and cloth manufacturer, and Charlotte Constanze Frowein.[7] At age three his family moved to the Netherlands where his mother's family lived.[7] Röntgen attended high school at Utrecht Technical School in Utrecht, Netherlands.[7] He followed courses at the Technical School for almost two years.[8] In 1865, he was unfairly expelled from high school when one of his teachers intercepted a caricature of one of the teachers, which was drawn by someone else.

Without a high school diploma, Röntgen could only attend university in the Netherlands as a visitor. In 1865, he tried to attend Utrecht University without having the necessary credentials required for a regular student. Upon hearing that he could enter the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich (today known as the ETH Zurich), he passed the entrance examination and began his studies there as a student of mechanical engineering.[7] In 1869, he graduated with a PhD from the University of Zurich; once there, he became a favourite student of Professor August Kundt, whom he followed to the newly founded German Kaiser-Wilhelms-Universität in Strasbourg.[9]

Career

In 1874, Röntgen became a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg. In 1875, he became a professor at the Academy of Agriculture at Hohenheim, Württemberg. He returned to Strasbourg as a professor of physics in 1876, and in 1879, he was appointed to the chair of physics at the University of Giessen. In 1888, he obtained the physics chair at the University of Würzburg,[10] and in 1900 at the University of Munich, by special request of the Bavarian government.

Röntgen had family in Iowa in the United States and planned to emigrate. He accepted an appointment at Columbia University in New York City and bought transatlantic tickets, before the outbreak of World War I changed his plans. He remained in Munich for the rest of his career.

During 1895, at his laboratory in the Würzburg Physical Institute of the University of Würzburg, Röntgen was investigating the external effects from the various types of vacuum tube equipment—apparatuses from Heinrich Hertz, Johann Hittorf, William Crookes, Nikola Tesla and Philipp von Lenard—when an electrical discharge is passed through them.[11][12] In early November, he was repeating an experiment with one of Lenard's tubes in which a thin aluminium window had been added to permit the cathode rays to exit the tube but a cardboard covering was added to protect the aluminium from damage by the strong electrostatic field that produces the cathode rays. Röntgen knew that the cardboard covering prevented light from escaping, yet he observed that the invisible cathode rays caused a fluorescent effect on a small cardboard screen painted with barium platinocyanide when it was placed close to the aluminium window.[10] It occurred to Röntgen that the Crookes–Hittorf tube, which had a much thicker glass wall than the Lenard tube, might also cause this fluorescent effect.

In the late afternoon of 8 November 1895, Röntgen was determined to test his idea. He carefully constructed a black cardboard covering similar to the one he had used on the Lenard tube. He covered the Crookes–Hittorf tube with the cardboard and attached electrodes to a Ruhmkorff coil to generate an electrostatic charge. Before setting up the barium platinocyanide screen to test his idea, Röntgen darkened the room to test the opacity of his cardboard cover. As he passed the Ruhmkorff coil charge through the tube, he determined that the cover was light-tight and turned to prepare for the next step of the experiment. It was at this point that Röntgen noticed a faint shimmering from a bench a few feet away from the tube. To be sure, he tried several more discharges and saw the same shimmering each time. Striking a match, he discovered the shimmering had come from the location of the barium platinocyanide screen he had been intending to use next.

Röntgen speculated that a new kind of ray might be responsible. 8 November was a Friday, so he took advantage of the weekend to repeat his experiments and made his first notes. In the following weeks, he ate and slept in his laboratory as he investigated many properties of the new rays he temporarily termed "X-rays", using the mathematical designation ("X") for something unknown. The new rays came to bear his name in many languages as "Röntgen rays" (and the associated X-ray radiograms as "Röntgenograms").

At one point while he was investigating the ability of various materials to stop the rays, Röntgen brought a small piece of lead into position while a discharge was occurring. Röntgen thus saw the first radiographic image: his own flickering ghostly skeleton on the barium platinocyanide screen. He later reported that it was at this point that he decided to continue his experiments in secrecy, fearing for his professional reputation if his observations were in error.

About six weeks after his discovery, he took a picture—a radiograph—using X-rays of his wife Anna Bertha's hand.[6] When she saw her skeleton she exclaimed "I have seen my death!"[13] He later took a better picture of his friend Albert von Kölliker's hand at a public lecture.

Röntgen's original paper, "On A New Kind of Rays" (Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen), was published on 28 December 1895. On 5 January 1896, an Austrian newspaper reported Röntgen's discovery of a new type of radiation. Röntgen was awarded an honorary Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Würzburg after his discovery. He also received the Rumford Medal of the British Royal Society in 1896, jointly with Philipp Lenard, who had already shown that a portion of the cathode rays could pass through a thin film of a metal such as aluminium.[10] Röntgen published a total of three papers on X-rays between 1895 and 1897.[14] Today, Röntgen is considered the father of diagnostic radiology, the medical speciality which uses imaging to diagnose disease.

A collection of his papers is held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[15]

Personal life

Röntgen was married to Anna Bertha Ludwig for 47 years until her death in 1919 at age 80. In 1866 they met in Zürich at Anna's father's café, Zum Grünen Glas. They got engaged in 1869 and wed in Apeldoorn, Netherlands on 7 July 1872; the delay was due to Anna being six years Wilhelm's senior and his father not approving of her age or humble background. Their marriage began with financial difficulties as family support from Röntgen had ceased. They raised one child, Josephine Bertha Ludwig, whom they adopted at age 6 after her father, Anna's only brother, died in 1887.[16]

He inherited two million Reichsmarks after his father's death.[17] For ethical reasons, Röntgen did not seek patents for his discoveries, holding the view that they should be publicly available without charge. After receiving his Nobel prize money, Röntgen donated the 50,000 Swedish krona to research at the University of Würzburg. Although he accepted the honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine, he rejected an offer of lower nobility, or Niederer Adelstitel, denying the preposition von (meaning "of") as a nobiliary particle (i.e., von Röntgen).[18] With the inflation following World War I, Röntgen fell into bankruptcy, spending his final years at his country home at Weilheim, near Munich.[11] Röntgen died on 10 February 1923 from carcinoma of the intestine, also known as colorectal cancer.[19] In keeping with his will, all his personal and scientific correspondence were destroyed upon his death.[20] He was member in the Dutch Reformed Church.[21]

Honours and awards

In 1901, Röntgen was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics. The award was officially "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him".[22] Röntgen donated the 50,000 Swedish krona reward from his Nobel Prize to research at his university, the University of Würzburg. Like Marie and Pierre Curie, Röntgen refused to take out patents related to his discovery of X-rays, as he wanted society as a whole to benefit from practical applications of the phenomenon. Röntgen was also awarded Barnard Medal for Meritorious Service to Science in 1900.[23]

His honours include:

- Rumford Medal (1896)

- Matteucci Medal (1896)

- Elliott Cresson Medal (1897)

- Nobel Prize for Physics (1901)

- In November 2004 IUPAC named element number 111 roentgenium (Rg) in his honour. IUPAP adopted the name in November 2011.

- 'Route Röntgen', street at CERN, Geneva, Switzerland officially registered 2013.

In 1907 he became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[24]

Legacy

Today, in Remscheid-Lennep, 40 kilometres east of Röntgen's birthplace in Düsseldorf, is the Deutsches Röntgen-Museum.[25]

In Würzburg, where he discovered X-rays, a non-profit organization maintains his laboratory and provides guided tours to the Röntgen Memorial Site.[26]

World Radiography Day: World Radiography Day is an annual event promoting the role of medical imaging in modern healthcare. It is celebrated on 8 November each year, coinciding with the anniversary of the Röntgen's discovery. It was first introduced in 2012 as a joint initiative between the European Society of Radiology, the Radiological Society of North America, and the American College of Radiology.

Röntgen Peak in Antarctica is named after Wilhelm Röntgen.[27]

Minor planet 6401 Roentgen is named after him.[28]

References

- Segovia-Buendía, Cristina (22 July 2020). "Röntgens Wurzeln im Bergischen". Lüttringhauser Anzeiger (in German).

- Jain, C. "Spouse - source from Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen Biographical". Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen Biographical.

- "Röntgen". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923) – Ontdekker röntgenstraling". historiek.net. 31 October 2010.

- Novelize, Robert. Squire's Fundamentals of Radiology. Harvard University Press. 5th edition. 1997. ISBN 0-674-83339-2 p. 1.

- Stoddart, Charlotte (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Wilhelm Röntgen". University of Washington: Department of Radiology. 7 January 2015.

- Rosenbusch, Gerd. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen: The Birth of Radiology. p. 10.

- Trevert, Edward (1988). Something About X-Rays for Everybody. Madison, Wisconsin: Medical Physics Publishing Corporation. p. 4. ISBN 0-944838-05-7.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 694.

- Nitske, Robert W., The Life of W. C. Röntgen, Discoverer of the X-Ray, University of Arizona Press, 1971.

- Agar, Jon (2012). Science in the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7456-3469-2.

- Landwehr, Gottfried (1997). Hasse, A (ed.). Röntgen centennial: X-rays in Natural and Life Sciences. Singapore: World Scientific. pp. 7–8. ISBN 981-02-3085-0.

- Wilhelm Röntgen, "Ueber eine neue Art von Strahlen. Vorläufige Mitteilung", in: Aus den Sitzungsberichten der Würzburger Physik.-medic. Gesellschaft Würzburg, pp. 137–147, 1895; Wilhelm Röntgen, "Eine neue Art von Strahlen. 2. Mitteilung", in: Aus den Sitzungsberichten der Würzburger Physik.-medic. Gesellschaft Würzburg, pp. 11–17, 1896; Wilhelm Röntgen, "Weitere Beobachtungen über die Eigenschaften der X-Strahlen", in: Mathematische und Naturwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen aus den Sitzungsberichten der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, pp. 392–406, 1897.

- "Fundamental contributions to the X-ray: the three original communications on a new kind of ray / Wilhelm Conrad Röentgen, 1972". National Library of Medicine.

- Glasser (1933: 63)

- Hans-Erhard Lessing: Eminence thanks to fluorescence – Wilhelm Röntgen. German Life (Grantsville MD) Oct/Nov 1995 pp. 40–42

- "Radiation Safety – Historical Figures – Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen". Michigan State University. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Glasser, Otto (1933). Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays. London: John Bale, Sons and Danielsson, Ltd. p. 305. OCLC 220696336.

- "Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was born on March 27, 1845".

- Knecht-van Eekelen, Annemarie de (2019). Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen: The Birth of Radiology. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 9783319976617.

Wilhelm Conrad and his father were members of the Dutch Reformed Church, the mainstream Protestant.

- See https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1901/rontgen/facts/ and Jost Lemmerich: Röntgen Rays Centennial 1895-1995, Würzburg 1995, ISBN 3-923959-28-1.

- "Award of Bernard Medal". Columbia Daily Spectator. Vol. XLIII, no. 57. New York City. 23 May 1900. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "W.C. Röntgen (1845–1923)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Deutsches Röntgen-Museum at roentgen-museum.de

- Röntgen Memorial Site at wilhelmconradroentgen.de

- Röntgen Peak. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer

- "(6401) Roentgen". (6401) Roentgen In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. 2003. p. 530. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_5844. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7.

External links

- Wilhelm Röntgen on Nobelprize.org

- Annotated bibliography for Wilhelm Röntgen from the Alsos Digital Library Archived 3 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen Biography

- The Cathode Ray Tube site

- First X-ray Photogram

- The American Roentgen Ray Society

- Deutsches Röntgen-Museum (German Röntgen Museum, Remscheid-Lennep)

- Works by or about Wilhelm Röntgen at Internet Archive

- Works by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Röntgen Rays: Memoirs by Röntgen, Stokes, and J.J. Thomson (circa 1899)

- The New Marvel in Photography, an article on and interview with Röntgen, in McClure's magazine, Vol. 6, No. 5, April 1896, from Project Gutenberg

- Röntgen's 1895 article, on line and analyzed on BibNum [click 'à télécharger' for English analysis]

- Works by Wilhelm Röntgen at Open Library

- Newspaper clippings about Wilhelm Röntgen in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW