Witch trials in England

In England, witch trials were conducted from the 15th century until the 18th century. They are estimated to have resulted in the death of perhaps 500 people, 90 percent of whom were women. The witch hunt was at its most intense stage during the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the Puritan era of the mid-17th century.[1]

History

Chronology

Witch trials are known to have occurred in England during the Middle Ages. These cases were few, and mainly concerned cases toward people of the elite or with ties to the elite, often with a political purpose.[2] Examples of these were the trials against Eleanor Cobham and Margery Jourdemayne in 1441, which resulted in lifetime imprisonment for the former, and an execution for heresy for the latter.

It was, however, not until the second half of the 16th century that a widescale witch hunt took place in England. The cases became more common in the end of the 16th century and the early 17th century, particularly since the succession of James VI and I to the throne. King James had shown a great interest in witch trials since the Copenhagen witch trials in 1589, which had inspired the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland in 1590. When he succeeded to the English throne in 1603, he sharpened the English Witchcraft Act the following year.

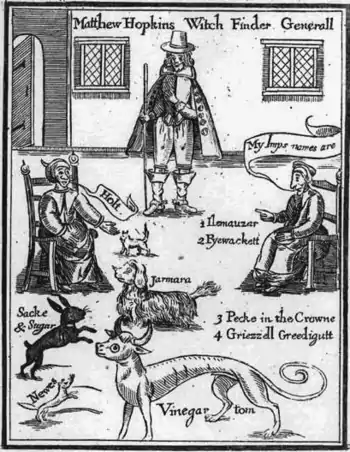

Witch trials were most frequent in England in the first half of the 17th century. They reached their most intense phase during the English civil war of the 1640s and the Puritan era of the 1650s. This was a period of intense witch hunts, known for witch hunters such as Matthew Hopkins.

Legal situation

The Witchcraft Act 1542 was enacted in England; but was repealed in 1547. The Witchcraft Act 1563 introduced the death penalty for any sorcery used to cause someone's death. In 1604 the Witchcraft Act was reformed to include anyone to have made a Pact with Satan.

The witch trials

In England, it was not as common as in some other nations to be accused of having attended a Witches' Sabbath or having made a Pact with Satan.[1] The typical victim of an English witch trial was a poor old woman with a bad reputation, who was accused by her neighbours of having a familiar and of having injured or caused harm to other people's livestock by use of sorcery.[1]

About 500 people are estimated to have been executed for witchcraft in England.[4][2]

Normally, people sentenced for witchcraft in England were executed by hanging. An exception was made when the person had committed another crime for which people were executed by burning at the stake. For example, when Mary Lakeland was burned at the stake in Ipswich on 9 September 1645 after having been judged for witchcraft, she was not burned for the crime of witchcraft, but because she had used witchcraft to murder her husband: this latter crime constituted petty treason, for which the punishment was burning.[5] Similar logic justified the execution by burning of Margaret Read, of King's Lynn, in 1590; and of Mary Oliver, of Norwich, in 1659.[6]

Political and Religious Influences

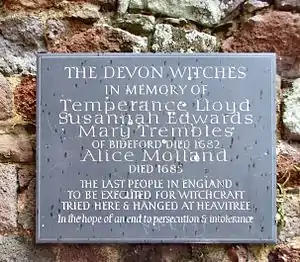

Historian John Callow argues in his 2022 book, The Last Witches of England, that witchcraft trials and convictions were influenced by political and religious tension between nonconformist Whigs, on the one hand, and the adherents of Anglican Toryism, on the other hand, after the English Civil War.[7]

End of witchcraft prosecutions

The 1682 Bideford witch trial resulted in the last people confirmed to have been executed for witchcraft in England, but the last person to be executed was probably Mary Hicks in 1716, whose story is recorded in an eight-page pamphlet published in the same year.[8]

Jane Wenham (died 1730) was one of the last people to be condemned to death for witchcraft in England, although her conviction was set aside. Her trial in 1712 is commonly but erroneously regarded as the last witch trial in England.[9]

The Witchcraft Act 1735 finally concluded prosecutions for alleged witchcraft in England after sceptical jurists, especially Sir John Holt (1642–1710), had already largely ended convictions of alleged witches under English law.

Colonies

Witch trials occurred also in the English colonies, where English law was applied. This was particularly the case in the Thirteen Colonies in North America. Examples of these were the Connecticut Witch Trials from 1647 to 1663. The most famous of these trials were the Salem witch trials in 1692. Two women were acquitted of witchcraft charges in the Province of Pennsylvania in 1683 after a trial in Philadelphia before William Penn.

See also

References

- Ankarloo, Bengt & Henningsen, Gustav (red.), Skrifter. Bd 13, Häxornas Europa 1400–1700: historiska och antropologiska studier, Nerenius & Santérus, Stockholm, 1987

- William E. Burns: Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia

- Sir John Holt. Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine National Portrait Gallery.

- Macfarlane, Alan; Sharpe, J.A. (1999). Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England : a regional and comparative study. Database:Taylor & Francis. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780203063668.

- David L. Jones The Ipswich Witch: Mary Lackland and the Suffolk Witch Hunts

- Nigel Pennick: Secrets of East Anglian Magic. 1995

- Callow, John (2022). "Chapter 8, The politics of death, and Chapter 9, Disenchantment". The Last Witches of England, A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-7883-1439-8.

- "Mary Hicks Witch of Huntingdon". Early Modern Medicine. 11 April 2018. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Guskin, Phyllis J. (Autumn 1981). "The Context of Witchcraft: The Case of Jane Wenham (1712)". Eighteenth-Century Studies. Charles Village, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 15 (1): 48–71. doi:10.2307/2738402. JSTOR 2738402.

Further reading

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1908). Devonshire Characters and Strange Events. London: John Lane.

- Barry, Jonathan (2012). Witchcraft and Demonology in South-West England, 1640-1789. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Callow, John (2022). The Last Witches of England, A Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-7883-1439-8. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.