Workplace wellness

Workplace wellness, also known as corporate wellbeing outside the United States, is a broad term used to describe activities, programs, and/or organizational policies designed to support healthy behavior in the workplace. This often involves health education, medical screenings, weight management programs, and onsite fitness programs or facilities. Recent developments in wearable health technology have led to a rise in self-tracking devices as workplace wellness.[1] Other common examples of workplace wellness organizational policies include allowing flex-time for exercise, providing onsite kitchen and eating areas, offering healthy food options in vending machines, holding "walk and talk" meetings, and offering financial and other incentives for participation.[2] Over time, workplace wellness has expanded from single health promotion interventions to describe a larger project intended to create a healthier working environment.

Companies most commonly subsidize workplace wellness programs in the hope they will reduce costs on employee health benefits like health insurance in the long run.[3] Although the academic debate is still unsettled, existing research has failed to establish a clinically significant difference in health outcomes, prove a return on investment, or demonstrate causal effects of treatments.[4] The largest benefits have been observed in groups that were already attempting to manage health concerns, which indicates a strong possibility of selection bias.[5] Additionally, this rationale has been critiqued for conflating productivity with physical and emotional wellbeing and prioritizing profit-centric measures over genuine attempts to create a healthy workplace environment.[6]

History

Wellness programs originated in the early 1900s, as labor unions fought for workers' rights and as employers saw the advantages of having a vital, alert, and rested workforce. A few key manufacturers invested in programs to keep their employees healthy and productive. For example, in 1905 Milton Hershey started building a leisure park for employees of the Hershey Chocolate Factory, wanting a "more pleasant environment for workers and residents than any typical factory town of the time".[7] We witnessed the implementation of regulated hours, negotiated salaries, and a fresh emphasis on occupational risks during this time.

1950s

In the 1950s, as America was recovering from the Second World War, employers were faced with an influx of returning veterans, as well as an increase in women entering the workforce. Companies started using a more structured approach to their employees' wellbeing, with the introduction of alcoholism-related programs to help reduce workplace accidents and stop alcohol and substance abuse. These initiatives took shape as Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), expanding to include help for mental health issues such as depression and PTSD. Larger corporations also experimented with new employee fitness programs, promoting the importance of physical activity as well as leisure time. In the later half of the decade, Dr. Halbert L. Dunn, chief of the National Office of Vital Statistics, introduced the concept of "high-level wellness" to encourage individuals to maximize their potential progress towards better living.[8] His work didn't significantly change workplace wellness yet, but it laid the groundwork for what was to come in the next 20 years.

1970s

The 1970s was a time of great cultural turbulence, where marginalized groups fought for equality, technological advancements changed how we work, and the world saw major financial inflation. At work, employers now bore the brunt of financial responsibility for their employees' health care costs. Emerging studies also showed the cost of employees’ unhealthy habits—namely, smoking, alcoholism, poor nutrition, and preventable injuries—made the cases even stronger for employer intervention. Employers were chiefly concerned with reducing both healthcare claims and workers’ compensation cases. New “workplace health promotion” programs were one way of combating that. In 1971, The U.S. Dept. of Labor establishes the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) to ensure safe and healthful working conditions.[9] Researchers also link this expanding interest in employer-sponsored wellness with broader cultural movements towards occupational safety, behavioral changes to improve health, and recreational fitness.

1980s

During the 1980s, physical fitness was the main focus in many newer corporate wellness programs. During the week, more people were becoming sedentary and working at desks with Personal Computers (PCs). Working hours slightly increased to around 43 per week, thanks to corporate culture that encouraged long hours as a sign of dedication to the company. Culturally, there are huge increases in cycling, jogging, aerobics, health clubs and gyms, and even marathoning. At this time, some larger corporations built on-site fitness centers and started offering aerobic classes during lunch breaks or evenings. For the first time, scholarly journals started legitimizing workplace wellness programs as a means to reduce absenteeism and potentially attract top talent. The biggest development was in smoking cessation. Early in the decade, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop wrote a report that compared the addictive properties in nicotine to those found in heroin and cocaine and challenged Americans to create a “smoke-free society by 2000.”[10]

1990s–2000s

During the 1990s to 2000s, corporate wellness programs were still focusing on risk management and trying to make a dent in ballooning healthcare costs. Outcomes-based wellness programs were all the rage, requiring participants to achieve specified health-related goals in order to receive a reward or incentive (for example, lowering your blood pressure or BMI within a certain time frame). Many programs tried using punitive measures, increasing healthcare premiums for employees deemed unhealthy. Low participation rates and high failure rates made these programs unsuccessful. The reason being that this style of wellness program was exclusive to certain groups, did little to boost morale or encourage positive change, and ignored all the other employees who needed encouragement. Furthermore, outcomes-based wellness was complicated by legal issues, ADA compliance, and concerns about giving healthy employees preferential treatment.

Rationale

There are numerous reasons to implement workplace wellness programs into the workplace. To begin, many Americans spend the majority of their time in the workplace. Additionally, the cost of healthcare is continually rising as result of chronic diseases in the US, workplace wellness programs can help abate this cost. Workplace wellness programs were once thought to also decrease overall cost of healthcare for participants and employers.

Unfortunately, workplace wellness programs have been shown not to prevent the major shared health risk factors specifically for CVD and stroke.[11] Since preventing these major health risks through workplace wellness can't help decreasing costs for both parties, the implementation of these programs is quite controversial.

While the stated goal of workplace wellness programs is to improve employee health, many US employers have turned to them to help alleviate the impact of enormous increases in health insurance premiums[12] experienced over the last decade. Some employers have also begun varying the amount paid by their employees for health insurance based on participation in these programs.[13] Cost-shifting strategies alone, through high copayments or coinsurance may create barriers to participation in preventive health screenings or lower medication adherence and hypertension.[14] While it was once believed that for every dollar spent on worksite wellness programs, medical costs fell by $3.27,[15] that hypothesis was disproven by a subordinate of the author of the original study.[16] The subordinate was working on behalf of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

One of the reasons for the growth of healthcare costs to employers is the rise in obesity-related illnesses brought about by lack of physical activity, another is the effect of an ageing workforce and the associated increase in chronic health conditions driving higher health care utilization. In 2000 the health costs of overweight and obesity in the US were estimated at $117 billion.[17] Each year obesity contributes to an estimated 112,000 preventable deaths.[18] An East Carolina University study of individuals aged 15 and older without physical limitations found that the average annual direct medical costs were $1,019 for those who are regularly physically active and $1,349 for those who reported being inactive. Being overweight increases yearly per person health care costs by $125, while obesity increases costs by $395.[17] A survey of North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services employees found that approximately 70 cents of every healthcare dollar was spent to treat employees who had one or more chronic conditions, two thirds of which can be attributed to three major lifestyle risk factors: physical inactivity, poor diet, and tobacco use.[19] Obese employees spend 77 percent more on medications than non-obese employees and 72 percent of those medical claims are for conditions that are preventable.[20]

According to Healthy Workforce 2010 and beyond, a joint effort of the US Partnership for Prevention and the US Chamber of Commerce, organizations need to view employee health in terms of productivity rather than as an exercise in health care cost management. The emerging discipline of Health and Productivity Management (HPM) has shown that health and productivity are "inextricably linked" and that a healthy workforce leads to a healthy bottom line. There is now strong evidence that health status can impair day-to-day work performance (e.g., presenteeism) and have a negative effect on job output and quality.[20] Current recommendations for employers are not only to help its unhealthy population become healthy but also to keep its healthy population from becoming sick. Employers are encouraged to implement population-based programs including health risk appraisals and health screenings in conjunction with targeted interventions.[14]

However, a large and growing body of research shows that workplace wellness has far more deleterious effects on employee health than benefits, and that there are no savings whatsoever.[11] Indeed, the most recent winner of the industry's award for the best program admitted to violating clinical guidelines and fabricating outcomes improvement.[21]

Benefits

Investing in worksite wellness programs not only aims to improve organizational productivity and presenteeism, but also offers a variety of benefits associated with cost savings and resource availability. A study performed by Johnson & Johnson (J&J) indicated that wellness programs saved organizations an estimated $250 million on health care costs between 2002 and 2008. Workplace wellness interventions performed on high-risk cardiovascular disease employees indicated that at the end of a six-month trial, 57% were reduced to a low-risk status. These individuals received not only cardiac rehabilitation health education but exercise training as well.[22] Further, studies performed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and J&J have revealed that organizations that incorporated exercise components into their wellness programs not only decreased healthcare costs by 30% but improved lost work days by 80%.[22] Thus, investing in preventative health practices has proven to not only be more cost effective in resource spending but in improving employee contributions towards high-cost health claims.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studied strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease and found that over a two- to five-year period, companies with comprehensive workplace wellness programs and appropriate health plans in place can yield $3 to $6 for each dollar invested and reduced the likelihood of employee heart attacks and strokes.[23] Also, a 2011 report by Health Fairs Direct which analyzed over 50 studies related to corporate and employee wellness, showed that the return on investment (ROI) on specific wellness related programs ranged between $1.17 to $6.04.[24] In general, it is estimated that worksite health promotion programs result in a benefit-to-cost ratio of $3.48 in reduced health care costs and $5.82 in lower absenteeism costs per dollar invested, according to the Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services.[25] Additionally, worksite health programs can improve productivity, increase employee satisfaction, demonstrate concern for employees, and improve morale in the workplace.[26]

Leadership involvement in wellness programs can additionally impact employee health outcomes just as well as the programs themselves. A study performed by David Chenoweth indicated the managers who were passionate and committed about their wellness programs increased employee engagement by 60%, even if their wellness goals were not achieved. Leaders are not only tasked with creating the organizational culture but also in coaching and motivating employees to be engaged in that culture.[27]

However, it turns out that employees generally detest these intrusive programs, and wellness's "Net Promoter Score" of -52 places it last on the list of all industries in user satisfaction.[28]

Barriers

The major barrier to further implementation of these programs is the increasing realization that they fail to produce benefits and may harm employees.[11] Savings are so elusive that a $3 million reward is offered for anyone who can find any.[29] In 2018, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) found no positive impact.[30] Also in 2018, Medicare found no savings.[31] Further, the NBER study concluded that the previous estimates of savings were largely invalid, due to a pervasive error in study design.[32]

Low participation rates by employees could significantly limit the potential benefits of participating in workplace wellness programs, as could systematically differences between participants and non-participants. Research performed by Gallup indicated that out of the 60% of employees who were aware of their company offered a wellness program only 40% participated.[33] A 2008 study[34] from the University of Minnesota provided insight into the likelihood of employee participation in an exercise promotion program. Their findings illustrate barriers to program participation that may be applicable to other types of programs and workplace settings. Employees were offered a financial incentive to attend a designated set of fitness facilities at least 8 times per month during the study period, and researchers administered a survey to over 3,000 program participants and non-participants to better understand their decision to participate. The research team included survey questions to assess each employee's attitudes and practices related to fitness prior to the program being offered, their marginal utility related to the financial incentive offered, the marginal cost of exercising (based on the cost of time and the financial cost of fitness center membership), prior history of chronic disease, and demographic characteristics related to age, gender, race and ethnicity, income, and employment type within the university system. Based on these survey responses, researchers reported the marginal effects related to the probability of 1) signing up for the program and 2) meeting program participation criteria by exercising 8 times per month to receive the financial incentive.

Employees with a higher time cost of exercise, calculated by the campus where the employee worked and by the number of participating fitness sites in the employee's home zip code, had a lower probability of signing up for and completing the program. Younger workers (ages 18–34) were more likely to sign up for the program relative to older employees, and women were more likely to sign up for the program than men. Researchers also found that employees with diabetes or low back pain were less likely to participate.

Program participation reflects a different trend. When researchers investigated the likelihood that an individual would be a regular program exerciser, defined as a participant in the program who checked in at a participating facility at least 8 times per month, for at least 50% of the time period for which the financial incentive was offered. Program participation in this sense means that an employee both signed up and completed the criteria to receive the reward. Regular exercises were more likely to be older (ages 55+), male, and to be classified as regular exercisers before the program was offered. These findings suggest that there may be differences between employees who would like to, or intend to, participate in certain workplace programs, and those who are likely to be able to participate and benefit. While this study focuses specifically on exercise and participation, lessons regarding the time cost of participation, location barriers to participation, and age and gender differences in participation rates are all important considerations for a firm interested in designing an effective workplace wellness program, especially if the goal is to promote a new behavior.

Ongoing management support and accountability are critical to successful worksite health promotion programs. Per research performed by Gallup, "Managers are uniquely positioned to ensure that each of their employees knows about the company's wellness program and to encourage team members to take part." By engaging workers in this organizational culture, employees become 28% more likely to participate in wellness programs than the average employee. Methods in which leaders can overcome the barrier of engagement is to not only model behaviors of the program but to consistently and effectively communicate the value of the wellness programs to employees. By creating the time and focus to improve the overall health and wellness of employees, managers can present many health and costs benefits to all members of the organization.[33]

Framework

Workplace wellness programs can be categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary prevention efforts, or incorporate elements from multiple types.[35] Primary prevention programs usually target an employee population which is already considered healthy and encourages workers to more frequently engage in health behaviors that will encourage ongoing good health (such as stress management, exercise and healthy eating). Secondary prevention programs are intended to reduce behavior which is considered a risk factor for poor health (such as smoking cessation programs and screenings for high blood pressure). Tertiary health programs are designed to address existing health problems (for example, by encouraging employees to better adhere to specific medication or self-managed care guidelines).

Worksite wellness programs including nutrition and physical activity components may occur separately or as part of a comprehensive worksite health promotion program addressing a broader range of objectives such as smoking cessation, stress management, and weight loss. A conceptual model has been developed by the Task Force for Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) and serves as an analytic framework for workplace wellness and depicts the components of such comprehensive programs.[36] These components include worksite interventions including 1) environmental changes and policy strategies, 2) informational messages, and 3) behavioral and social skills or approaches.

Worksite environmental change and policy strategies are designed to make healthy choices easier. They target the whole workforce rather than individuals by modifying physical or organizational structures. Examples of environmental changes may include enabling access to healthy foods (e.g., through modification of cafeteria offerings or vending machine content) or enhancing opportunities to engage in physical activity (e.g., by providing onsite facilities for exercise). Policy strategies may involve changing rules and procedures for employees, such as offering health insurance benefits, reimbursement for health club memberships, healthy food and beverage policies or allowing time for breaks or meals at the worksite.

Informational and educational strategies attempt to build the knowledge base necessary to inform optimal health practices. Information and learning experiences facilitate voluntary adaptations of behavior conducive to health. Examples include health-related information provided on the company intranet, posters or pamphlets, nutrition education software, and information about the benefits of a healthy lifestyle, including diet and exercise. Behavioral and social strategies attempt to influence behaviors indirectly by targeting individual cognition (awareness, self-efficacy, perceived support, intentions) believed to mediate behavior changes. These strategies can include structuring the leadership involvement and social environment to provide support for people trying to initiate or maintain lifestyle behavior changes, for example, weight change. Such interventions may involve individual or group behavioral counselling, skill-building activities such as cue control, use of rewards or reinforcement, and inclusion of coworker, manager/leader or family members for support.[37]

Health economics of workplace wellness programs

Wellness programs are typically employer sponsored and are created with the theory that they will encourage healthy behaviors and decrease overall health costs over time.[38] Wellness programs function as Primary Care interventions as they are an example of primary prevention methods to reduce risks to many diseases or conditions.[39]

Workplace wellness programs have been around since the 1970s[40] and have gained new popularity as the push for cost savings in the health delivery system becomes more evident as a result of high health care expenditures in the U.S. Employer wellness programs have shown to have a return on investment (ROI) of about $3 for every $1 invested over a multi-year period,[41] making them appealing to many as an effective way to achieve results and control costs. Most recently, the 2016 winner of the "best wellness program" award, Wellsteps, was shown to have harmed employees at the Boise School District and fabricated its savings figures.[42]

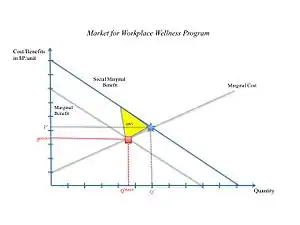

Workplace wellness programs have many components to help improve health outcomes and decrease health disparities. These components include smoking cessation programs, fitness center memberships, nutrition aids, and biometric screenings, often in exchange for health insurance premium reductions.[43] The benefits of wellness programs are not limited to corporations and their employees; Otenyo and Smith argue that engaging in such programs produces positive spillover effects for society that are not reflected in markets, leading to them under consumption.[44]

Workplace wellness programs benefit employers as well; while the various components of the wellness programs helps to keep employees healthy, employers are able to increase recruitment and retention of workers.[45] Some employers have also utilized penalties to improve employee participation within the company wellness program.[46] While wellness programs promote healthier lifestyles and can bring significant cost savings, concerns about invasion of privacy and participation costs have arisen.[47]

The future of wellness programs as a valid method of preventative healthcare is still up for debate. Evidence of improved health outcomes for participants is mixed in terms of effectiveness.[43] Some studies attempt to address the question if "more is always better in the workplace," and the value that can be found through wellness program components and their outcomes.

One large study though, did not find health improvements for premium incentive-based workplace weight loss programs.[48]

Writing in the New York Times, Frank and Carroll laid out several concerns with wellness programs, including limitations in empirical studies and the possibility that employers use these programs to shift costs to employees.[49] That said, the 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation Employer Health Benefits Survey indicates that organizations continue to enact such programs due to their perceived benefits for employee health, morale, and productivity.[50]

Wellness programs have created a $6 billion industry due to its reputation of reducing health care costs. In their 2013 Workplace Wellness Programs Study, RAND Corporation researchers concluded that while lifestyle-focused wellness programs can reduce risk factors and motivate healthy behavior, the reductions in healthcare costs are less than previously reported. However, most wellness studies that report the positive results of the wellness programs are not of high quality, indicate only short-term results, and do not justify causation.[51] Moreover, these studies are sponsored by their own wellness industry, creating bias. Other studies find that the programs don't improve health outcomes or reduce health care costs.

In fact, a decrease of employers' health care costs has been simply passed on the employees. Based on the Affordable Care Act, employers are able to charge unhealthy employees up to 30 to 50 percent more of total premium costs. This has resulted in pushback from employees who have not met mandated health goals like quitting smoking or reducing body mass index (BMI).[52]

On the other hand, research on the 2003 PepsiCo Healthy Living program suggests that the wellness plan helps reduce health care costs after the third year of implementing the disease management components of the program.[53] But, the wellness program does not show evidence of lower costs due to the lifestyle changes in the short run.

This result is consistent with the one-year study with the 3,300 employees of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2016.[16] The study indicates that participation in a wellness program does not result in healthier employees or reduced health care costs.[54]

The research also shows that without an incentive, about 46.9 percent participated in the wellness program. Then, the change in monetary incentive from $0 to $100 increases participation by 12 percent, from 46.9 percent to 58.5 percent. An additional incentive of $200 increases the participation from 58.5 to 62.5 percent.

This study shows that when the company increases participants by only 4.5 percent or reduce 4.5 percent of non-participants or high medical spending employees, it will compensate the total cost of the specific wellness program. This result is consistent with other studies that the wellness programs do not help lower health care costs, but only have passed on the costs to other employees. Regarding the employment and productivity, the participants believe that management places an importance on health, fitness, and safety. However, the study shows no significant difference on the happier feelings or more productive at work among the participants.

Workplace wellness programs have the potential to lead to healthier outcomes and decreased costs, but the economics are still unclear, and more research is required.

Affordable Care Act and effects on workplace wellness

There are conversations surrounding the role of the Affordable Care Act and in general insurance on its effects on workplace wellness. Sixty percent of Americans obtain their insurance coverage solely in their respective workspaces.[55] However, larger companies are more inclined to offer employee health insurance and wellness programs than those in small businesses. It is critical for workplace wellness to have increase participation, provisions under insurance coverage for small employers to increase incentives expands participation for small businesses.[56] The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes the Prevention and Public Health Fund whereby provisions are created to address and expand community prevention, public health infrastructure and training, clinical prevention, and workforce wellness research in the large American working demographic.[55]

The role of the ACA increases programs for worksite wellness is a strategy to tackle the growing rate of chronic diseases in the United States.[55] In a study by the CDC, the implementation of worksite wellness incurs a three-time investment over a dollar spent and have been reported positively by companies such as Johnson & Johnson, Citibank, Duke University, Chevron etc.[55]

Included in the Affordable Care Act are chronic diseases management to be offered in the essential health benefits.[57] As workers age, health care costs and chronic diseases such as depression, anxiety and diabetes are proportional to its growing increase.[55] Owing to this increase, the negative effect on workplace productivity and presentism is declining. ACA implements these management benefits to reduce the declining and negative effects.[57]

In the CDC study on workplace wellness and ACA, the solution resolves to health culture and its strength in workplaces given that only 26% reported that their employees have strong culture of health in their organizations.[55] In 2014, it was found that the Affordable Care Act expands incentive limit by 10 percent.[57] Implementing incentives such as discounts that puts value in health choices and behavior illustrated a 73% positive feedback.[55] In addition, increasing tax on sugar-sweetened drinks, would decrease obesity levels in US adults by 3.5%.[55] The study then concluded towards preventative practices and reform promotes health and quality on workers and increasing productivity.[55] Included with ACA's incentive plan is a non-discriminatory law or HIPAA to requiring availability to alternative wellness programs if need be.[57]

The Affordable Care Act has importance in contextualizing health care promotions in the workplace. The Affordable Care Act, in its revisions and improvements not only persuades workspaces both low and high wage industries to implement health care promotion. Small employers often are underrepresented in the surveys and data for ACA, low wage industries in the past have been underrepresented under the Affordable Care Act, however, with improvements in representation to cover both low and high earning workers, more participation can be seen in workplace wellness.[56]

Program components

Healthy People 2020 is a blueprint for a 10-year national initiative to improve the health of all Americans, "providing 42 topics and over 1,200 objectives to guide evidence-based practice".[58] "A shorter list of high priority topics are categorized into Leading Health Indicators (LHIs) highlighting collaborative actions that can be taken to impact American health outcomes."[58] Employers can use Healthy People 2020 objectives to focus business-sponsored health promotion/disease prevention efforts and measure worksite and community-wide outcomes against national benchmarks using evidence-based practices. As defined by Healthy People 2020, a comprehensive worksite health promotion program contains five program elements:

- Health education, which focuses on skill development and lifestyle behavior change along with information dissemination and awareness building, preferably tailored to employees' interests and needs.

- Supportive social and physical environments. These include an organization's expectations regarding healthy behaviors, and implementation of policies that promote health and reduce risk of disease, including leadership support.[59][60]

- Integration of the worksite program into your organization's structure.

- Linkage to related programs like Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) and other programs to help employees balance work and family.

- Worksite screening programs (Health Risk Assessments, blood draws, biometric screening, genetic testing, etc.), ideally linked to medical care to ensure follow-up and appropriate treatment as necessary.

Partnership for Prevention includes two additional components:

- Support for individual behavior change with follow-up interventions.

- Evaluation and improvement processes to help enhance the program's effectiveness and efficiency.

Additionally, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that a workplace health program will be "coordinated and comprehensive" if strategies include "programs, policies, benefits, environmental supports, and links to the surrounding community designed to meet health and safety of employees."[61] Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), through its Total Worker Health program, offers an extensive list of resources to assist employers, employees, and practitioners with their efforts to implement and develop programs in their organizations that integrate employee health activities. Most of the publicly available reputable sources provides tips and tools but are not "off-the-shelf" or "turn-key solutions." Organizations wishing to obtain more assistance will find there are numerous private companies offering fee-based services.

The Partnership for Prevention offers extensive background and program-specific information in its Healthy People 2020 and Beyond report.[62]

Workplace health model

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a workplace health model incorporating elements and fundamental ideas of The Community Guide's framework and Healthy People 2020 in a coordinated approach to impact health at the workplace.[63] This approach should be "coordinated, systematic and comprehensive".[63]

Assessment

Program success and employee engagement require information to be obtained about the workplace, either formally (i.e. needs assessment) or informally (i.e. conversations with employees), collecting data regarding individual lifestyle, work environment, and organizational details.[63] Data should be collected for both employee interests and available aggregate data about health status, health issues or cultural survey data.[63] Engaging employees, including the leadership team, from the beginning of program planning and development will help drive commitment, responsibility, and participation; as well as, creating a culture of health and great place to work.[63] Additional information to assist with workplace assessment can be found using the CDC Assessment Module.[64]

Program planning

Next is to develop a strategic plan that considers the pertinent assessment results from a vantage point of both the individual's actions and environmental context in accordance with the direction from the governance structure.[63] This should always be completed prior to implementation or evaluation; however, keeping the end in mind (how will I evaluate this program to know it was successful?) will help drive the overall plan. The recommended strategy for "direction leadership and organization"[65] by the CDC includes: leadership support dedicated to championing wellness and modeling behaviors;[66][67] workplace Wellness Committee, Coordinator or Council; development of a resource list of available assets; defined mission, vision, goals, objectives and strategies; comprehensive communication plan; evidence-based practices; and data collection and analysis.[63][65] A thoughtful strategic plan will select and deliver interventions, policies, and programs that are most advantageous to the particulars of the employee population.[63][65] Additional resources can be found by visiting the CDC's Planning/Workplace Governance Module.[68]

Implementation

The implementation stage is where the rubber meets the road. Employees often see this stage as the "Wellness Program", and typically do not understand what goes into the process to provide a comprehensive strategic plan. Therefore, implementation occurs when the strategic plan executes the opportunities to support an employee's health.[63] The CDC recommends four main categories for interventions or strategies that successfully influence health: "health-related programs; health-related policies; health benefits; and environmental supports".[63][69]

Evaluation

To determine impact and success, evaluation is crucial to the longevity of a workplace wellness program. Everything from programs to policies to environment must be evaluated to determine return on investment (ROI), value on investment (VOI), health impact, employee satisfaction and sustainability.[63] "According to the CDC (2016), evaluations can often be overwhelming, time-consuming and expensive; so, focusing on relevant, salient, and useful information is key to quality evaluation practices. An evaluation tool should be designed to support the program process, quality improvement, and identification of gaps for future strategic plans."[63][70]

Workplace wellness best practices

According to research completed by Hoffman and Kennedy-Armbruster (2015), and published by the American College of Sports Medicine Health & Fitness Journal, the top nine workplace/worksite wellness best practices include:

- Leadership support (i.e., modeling, resource allocation, etc.)

- Relevant and personalized programs (using employee interests and available aggregate data)

- Partnership with employees, employer, organizations, and local community.

- Comprehensive and evidence-based programs (using eight dimensions of wellness can be a helpful tool- emotional, environmental, financial, intellectual, occupational, physical, social, and spiritual[71])

- Implementation that is well planned, coordinated, fully executed, and evaluated for success and accountability

- Employee engagement through organization and planning wellness efforts

- Formal and comprehensive communication strategies/plan

- Data driven decisions that include measurement, evaluation, reporting, and analytics

- HIPAA compliant programs."[72]

Importance of leadership support

Leadership support has been indicated as a benefit, best practice and a key element of the CDC to be part of the Workplace Health Model; therefore, understanding research to sustain these claims is important for the success of programs. Below you find research to support how leadership involvement and commitment of wellness activities (i.e., physical activity) can impact health status (i.e., cardiovascular disease status).

Lawrence et al. (2015) indicates strengths and weakness of current worksite wellness models providing key considerations for the development of a strong program. Key strengths indicated were "leadership commitment, organizational culture and environmental structure" to build a culture of health, ultimately promoting the improvement among non-communicable diseases.[73] Furthermore, Lawrence et al. (2015) suggest that these characteristics are indicative of a "high-quality program regardless of the model used: 1) leadership support, 2) clear importance of health and wellness by organization culture and environment, 3) program responsiveness to changing needs, 4) utilization of current technology, and 5) support from community health programs".[73]

A recent survey conducted by Harris Poll and reported the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016) stated just over 30% of Americans indicate participation in worksite wellness programs, and 44% indicate that employee wellness is supported by their workplace culture.[74] Furthermore, this data indicates when senior leaders are involved and committed to wellness program initiatives 73% of employees feel their organization supports a healthy lifestyle and their overall well-being; however, only 4 of 10 Americans said that their leadership team supports wellness initiatives.[74] Further evidence reported by RAND (2013) stated "evidence from case studies suggests that for programs to be a success, senior managers need to consider wellness an organizational priority to shift the company culture. Buy-in from direct supervisors is crucial to generate excitement and connect employees to available resources."

Furthermore, Hoert, Herd, and Hambrick (2016) used the Leading by Example instrument to find "employees experiencing higher levels of leadership support reported higher wellness program participation, lower stress, and higher levels of health behaviors".[75] Stokes, Henley and Herget (2006) reported on findings from a wellness initiative pilot program using the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. This organization was selected as the pilot due to the leadership support model and its large size.[76] This program focused on "reducing major chronic diseases (including cardiovascular diseases), demonstrating the effectiveness of a wellness program model that includes a full-time department-level director, establish wellness committees to sustain work environments that promote and support employee health and wellness, and change policies and environments to help employees be more active, make healthier food choices, avoid tobacco, and manage stress".[76] Results after the first year of this program indicated that 62% of employees participated in at least one wellness activity, 51% exercising more often, 50% stating wellness programs as the most popular activity, 49% eating more fruits and vegetables, 27% were closer to a healthy weight, and 106 employees stopped smoking and 149 reduced tobacco use.[76]

Finally, Ross et al. (2013) report the increased importance of physical activity at the workplace with the increasing sedentary job responsibilities, and the positive effect of worksite physical activity programs have on health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and metabolic conditions.[77] Additionally, their research indicates appropriate models for these successes are through "a health and wellness culture driven by leadership support, specialized programs designed for the employee population, and strategic plans that partner with current organizational goals".[77]

Program development and best practices example

Example

The framework of The Community Guide, program components (goals and objectives) set out by Health People 2020, the Workplace Health Model outlined by the CDC, and other best practices provides a comprehensive foundation for a worksite wellness platform regarding program development, implementation, and evaluation. Using the components above, an employee (or employer) can use employee interest, employee aggregate health data, and the LHIs as priorities to guide goals and objectives, develop programs and evaluation to facilitate, collaborate, and motivate their employees to improve their health. The following example will use the above-mentioned workplace wellness program components as it relates to the goal of weight reduction by increased physical activity through leadership support in order to decrease cardiovascular disease, ultimately impacting the Healthy People 2020 LHI "Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity".[78] The following is a simplified example for (a fabricated) Company ABC:

Assessment

An employee (or Company ABC Human Resource Department) reviews the current aggregate data provided by the employer insurance company as it relates to weight, physical activity, and cardiovascular measures, including cholesterol, blood pressure, biometric screening, physical activity, smoking, or other indicators. Company ABC will review the available company culture survey results as it relates to wellness for both social and environmental supports. Conversations and focus groups will be established to assess and determine employee engagement, interests, concerns, and other wellness related brainstorming.

Implementation

Using The Community Guide, Health People 2020, CDC recommendations, and other peer-reviewed research (evidence-based programs) an organization can design and implement recommended intervention, policies, programs, or environmental supports to ensure the success of the desired goals and outcomes. Based on the CDC's recommendation to include a multidimensional intervention framework,[79] the wellness coordinator for Company ABC has decided on the following programs to support the goals of physical activity through leadership support to help improve cardiovascular health.

- Promoting leadership success stories on with physical activity and movement through the organization's monthly newsletter

- Marketing with leadership photos inviting participants to come to the planned event

- Revised smoking and smokeless tobacco policy which will be enforced by leadership support[80]

- Health coaches for increase physical activity, nutritional changes, and tobacco cessation, including quit kits and available pharmaceuticals in the onsite wellness clinic[80]

- Promotion of health insurance health coaches for physical activity and nutrition through telephonic support[81]

- Quarterly health education lunch and learn on cardiovascular health topics (cholesterol, heart disease, metabolic disease, etc.) as it relates to physical activity (including nutrition)[80]

- Implementation of recommended (informal) policy for walking meetings, especially led by senior leadership and managers

- Implement point-of-decision prompts to use the stairs[82]

- Physical activity challenge led by leaders at Company ABC[83]

- Free and onsite health risk assessment and blood draw events for employees, spouses and dependents[80]

- Onsite blood pressure cuffs for blood pressure self-monitoring[80]

Evaluation

Utilizing past aggregate data from health insurance claims and company culture survey from Company ABC a baseline will be established prior to the program implementation. Following the wellness coordinators strategic plan for Company ABC, measures post-program (1 year) will be collected, including an employee satisfaction survey, informal forums, a collection of corresponding year aggregate data from the insurance company and data from the annual culture survey.[84] Data analysis will be conducted on program successes, strengths, opportunities, threats, and weakness; furthermore, interpretation of results will be collected and reported back to the leadership team for review and support for the next year's strategic planning. Additional comparisons can be made to the Healthy People 2020 LHI's Report Card to determine how the employees of Company ABC are doing in comparison to the reported United States data, as well as how they are supporting the overall goals of the Healthy People 2020 goals.[85]

Impact

A meta-analysis of the literature on costs and savings associated with wellness programs, medical costs fell by about $3.27 for every dollar spent on wellness programs and absenteeism costs fell by about $2.73 for every dollar spent.[86] A 2019 study in the journal JAMA found that a workplace wellness program at BJ's Wholesale Club had a very limited impact. The study found no impact on health measures or health care costs, but participants in the study did report that they became more knowledgeable about health behaviors.[87][88]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a case study of a workplace wellness program at Capital Metro, the local transit authority in Austin, TX.[89] The study found that there was a reduction in costs associated with employee health care and absenteeism after the workplace welfare program was implemented.[89] In one large study of 1,542 participants across 119 workplaces, 57.7% of participants showed significant reductions in 7 of the 10 cardiovascular health risk categories studied.[90] Johnson & Johnson, one of the world's largest companies, has saved $250 million on health care costs within the last decade as a result of wellness programs; from 2002 to 2008, the return was $2.71 for every dollar spent.[22]

See also

References

- Charitsis, Vassilis (2019-03-31). "Survival of the (Data) Fit: Self-Surveillance, Corporate Wellness, and the Platformization of Healthcare". Surveillance & Society. 17 (1/2): 139–144. doi:10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12942. ISSN 1477-7487. S2CID 133187423.

- "Wellness and Health Promotion Programs Use Financial Incentives To Motivate Employees". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- Hull, Gordon; Pasquale, Frank (2018-03-01). "Toward a critical theory of corporate wellness". BioSocieties. 13 (1): 190–212. doi:10.1057/s41292-017-0064-1. ISSN 1745-8560. S2CID 148579184.

- Song, Zirui; Baicker, Katherine (2019-04-16). "Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 321 (15): 1491–1501. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3307. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 6484807. PMID 30990549.

- Jones, Damon; Molitor, David; Reif, Julian (2019-11-01). "What do Workplace Wellness Programs do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study*". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 134 (4): 1747–1791. doi:10.1093/qje/qjz023. ISSN 0033-5533. PMC 6756192. PMID 31564754.

- Till, Christopher (July 2019). "Creating 'automatic subjects': Corporate wellness and self-tracking". Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 23 (4): 418–435. doi:10.1177/1363459319829957. ISSN 1363-4593. PMID 30755035. S2CID 73420166.

- HERSHEY ENTERTAINMENT & RESORTS COMPANY. (n.d.). Hersheypark History. Hersheypark History | Hershey, PA. https://www.hersheypa.com/about-hershey/history/hersheypark-history.php.

- DUNN H. L. (1959). High-level wellness for man and society. American journal of public health and the nation's health, 49(6), 786–792. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.49.6.786

- United States Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.). Timeline | Occupational Safety and Health Administration. https://www.osha.gov/osha40/timeline.html.

- Schraufnagel, D. E. (2013). C. Everett Koop, M.D. (1916–2013). United States Surgeon General, 1982–1989. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 10(3), 276–276. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.201303-066ot

- Lewis, Al (1 January 2017). "The Outcomes, Economics, and Ethics of the Workplace Wellness Industry". Health Matrix: The Journal of Law-Medicine. 27 (1): 1.

- Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research Education Trust. (2007). Employer Health Benefits Survey.

- Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research Education Trust. (2007). Employer Health Benefits Survey Exhibit 6.18

- Healthy Workforce 2010 and Beyond. (2009). Partnership for Prevention. Labor, Immigration & Employee Benefits Division: U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

- Knapper, Joseph T.; Ghasemzadeh, Nima; Khayata, Mohamed; Patel, Sulay P.; Quyyumi, Arshed A.; Mensah, George A.; Tabuert, Kathryn (2015). "Time to Change Our Focus : Defining, Promoting, and Impacting Cardiovascular Population Health". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 66 (14): 1641–655. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.008. PMID 26293767.

- Jones, Damon; Molitor, David; Reif, Julian (January 2018). "What Do Workplace Wellness Programs Do? Evidence from the Illinois Workplace Wellness Study". NBER Working Paper No. 24229. doi:10.3386/w24229.

- "East Carolina University" (PDF). www.ecu.edu.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Healthy Workforce 2010 and Beyond. (2009). Partnership for Prevention. Labor, Immigration & Employee Benefits Division: U.S. Chamber of Commerce

- "Wellness award goes to workplace where many measures got worse". STAT. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- Berry, Leonard; Mirabito, Ann M.; Baun, William (December 2010). "What's the Hard Return on Employee Wellness Programs?". Harvard Business Review. SSRN 2064874.

- Reducing the Risk of Heart Disease and Stroke, Centers for Disease Control.

- "Abenity - Corporate perks and discount programs for employee, member, and alumni groups". www.abenity.com.

- Health Promotion Worksite Initiative, Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services.

- Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: The Fundamentals of Workplace Health Promotion. Wellness Council of America.

- Chenoweth. "Promoting employee well-being" (PDF).

- "Quiz: Which industry has the worst Net Promoter Score? (SPOILER ALERT: It's wellness.)". They Said What?. 2018-01-21. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- "The reward for showing your wellness program works is now $3 million!". They Said What?. 2017-12-09. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- "Study Finds Virtually Zero Benefit From Workplace Wellness Program In 1st Year". www.wbur.org. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- "Wellness programs aren't generating Medicare savings". Modern Healthcare. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- "NBER's Invalidation of Wellness: Behind the Headlines". AJMC. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- O'Boyle. "Why your workplace wellness program isn't working".

- Abraham, Jean M.; Feldman, Roger; Nyman, John A.; Barleen, Nathan (August 2011). "What Factors Influence Participation in an Exercise-Focused, Employer-Based Wellness Program?". INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 48 (3): 221–241. doi:10.5034/inquiryjrnl_48.03.01. PMID 22235547. S2CID 8766040.

- Goetzel, R.Z., Ozminkowski, R.J. The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annual Review of Public Health. 2008;29:303-323

- Anderson, Laurie M.; et al. (2009). "The Effectiveness of Worksite Nutrition and Physical Activity Interventions for Controlling Employee Overweight and Obesity". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 37 (4): 340–357. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003. PMID 19765507.

- Anderson, Laurie M.; Quinn, Toby A.; Glanz, Karen; Ramirez, Gilbert; Kahwati, Leila C.; Johnson, Donna B.; Buchanan, Leigh Ramsey; Archer, W. Roodly; Chattopadhyay, Sajal; Kalra, Geetika P.; Katz, David L. (October 2009). "The Effectiveness of Worksite Nutrition and Physical Activity Interventions for Controlling Employee Overweight and Obesity". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 37 (4): 340–357. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003. PMID 19765507.

- "Workplace Wellness" (PDF).

- Anderko, Laura; Roffenbender, Jason S.; Goetzel, Ron Z.; Howard, John; Millard, Francois; Wildenhaus, Kevin; DeSantis, Charles; Novelli, William (13 December 2012). "Promoting Prevention Through the Affordable Care Act: Workplace Wellness". Preventing Chronic Disease. 9: 120092. doi:10.5888/pcd9.120092. PMC 3523891. PMID 23237245.

- "The Evolution of Worksite Wellness". Corporate Wellness Magazine. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- "Workplace Wellness" (PDF).

- "Wellness award goes to workplace where many measures got worse". STAT. 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- "Workplace Wellness Programs (Updated)". Health Affairs - Health Policy Briefs. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- Otenyo, Eric E.; Smith, Earlene A. (2017). "An Overview of Employee Wellness Programs in Large U.S. Cities: Does Geography Matter?". Public Personnel Management. 46 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1177/0091026016689668. S2CID 133541237.

- "Advantages of Workplace Wellness Programs". SparkPeople. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- "Employers use penalties to push workers into wellness programs - Business Insurance". Business Insurance. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- "Privacy Concerns".

- Caloyeras, John P.; Liu, Hangsheng; Exum, Ellen; Broderick, Megan; Mattke, Soeren (2014). "Managing Manifest Diseases, But Not Health Risks, Saved PepsiCo Money Over Seven Years". Health Affairs. 33 (1): 124–131. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0625. PMID 26733703.

- Frakt, Austin; Carroll, Aaron E. (11 September 2014). "Do Workplace Wellness Programs Work? Usually Not". The New York Times.

- Claxton, Gary; Rae, Matthew; Damico, Anthony; Gregory, Young; McDermott, Daniel; Whitmore, Heidi (2019). "2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Mattke, Soeren; Liu, Hangsheng; Caloyeras, John; Huang, Christina; Van Busum, Kristin; Khodyakov, Dmitry; Shier, Victoria (2013). "Workplace Wellness Programs Study". RAND Corporation.

- Frakt, Austin; Carroll, Aaron E. (16 September 2013). "The Feel-Good Promise of Wellness Programs". Bloomberg Opinion.

- Patel, Mitesh S.; Asch, David A.; Troxel, Andrea B.; Fletcher, Michele; Osman-Koss, Rosemary; Brady, Jennifer; Wesby, Lisa; Hilbert, Victoria; Zhu, Jingsan; Wang, Wenli; Volpp, Kevin G. (January 2016). "Premium-Based Financial Incentives Did Not Promote Workplace Weight Loss In A 2013–15 Study". Health Affairs. 35 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0945. PMID 26733703.

- Greenfield, Rebecca (4 February 2018). "Workplace wellness programs aren't working, new research finds". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- Anderko, Laura (2012). "Promoting Prevention Through the Affordable Care Act: Workplace Wellness". Preventing Chronic Disease. 9: E175. doi:10.5888/pcd9.120092. ISSN 1545-1151. PMC 3523891. PMID 23237245.

- Hall, Jennifer L.; Kelly, Kevin M.; Burmeister, Leon F.; Merchant, James A. (2017-09-01). "Workforce Characteristics and Attitudes Regarding Participation in Worksite Wellness Programs". American Journal of Health Promotion. 31 (5): 391–400. doi:10.4278/ajhp.140613-QUAN-283. ISSN 0890-1171. PMID 26730552. S2CID 3472818.

- Mattke, Soeren; Liu, Harry H.; Caloyeras, John P.; Huang, Christina Y.; Van Busum, Kristin R.; Khodyakov, Dmitry; Shier, Victoria (2013-05-30). "Workplace Wellness Programs Study: Final Report". Rand Health Quarterly. 3 (2): 7. PMC 4945172. PMID 28083294.

- "Leading Health Indicators". Healthy People 2020. March 15, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- Aldana, S., Adams, T. "Worksite Wellness Implementation Guide" (PDF). Well Steps. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miller, S. (February 20, 2013). "Wellness Program 'Best Practices' Foster Success". Society for Human Resource Management. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- "Workplace Health Model". www.cdc.gov. March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- "Midcourse Review: LHIs - Healthy People 2020". www.healthypeople.gov.

- "Workplace Health Model | Workplace Health Promotion | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Assessment - Model - Workplace Health Promotion - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 26 January 2018.

- "Planning/Workplace Governance | Model | Workplace Health Promotion | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Leadership Support | Planning | Model | Workplace Health Promotion | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Partnership for Prevention". www.prevent.org. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Planning/Workplace Governance - Model - Workplace Health Promotion - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2 February 2018.

- "Implementation - Model - Workplace Health Promotion - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 23 January 2018.

- "Best Practices in Evaluating Worksite Health Promotion Programs" (PDF). staywell.com.

- "The Eight Dimensions of Wellness". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Hoffman, L., Kennedy-Armbruster, C. (2015). "Case Study Using Best Practice Design Principles for Worksite Wellness Programs". ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 19 (3): 30–35. doi:10.1249/FIT.0000000000000125. S2CID 218305757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cahalin, Lawrence P.; Kaminsky, Leonard; Lavie, Carl J.; Briggs, Paige; Cahalin, Brendan L.; Myers, Jonathan; Forman, Daniel E.; Patel, Mahesh J.; Pinkstaff, Sherry O. (2015-07-01). "Development and Implementation of Worksite Health and Wellness Programs: A Focus on Non-Communicable Disease" (PDF). Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Preventive Cardiology Update: Controversy, Concensus [sic], and Future Promise. 58 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2015.04.001. PMID 25936908.

- "Workplace Well-being Linked to Senior Leadership Support, New Survey Finds". 2016. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Hoert, Jennifer; Herd, Ann M.; Hambrick, Marion (May 2018). "The Role of Leadership Support for Health Promotion in Employee Wellness Program Participation, Perceived Job Stress, and Health Behaviors". American Journal of Health Promotion. 32 (4): 1054–1061. doi:10.1177/0890117116677798. PMID 27920214. S2CID 4908652.

- Stokes, George; Henley, Nancy; Herget, Casey (2006). "Creating a Culture of Wellness iN Workplaces". North Carolina Medical Journal. 67 (6): 445–448. doi:10.18043/ncm.67.6.445. PMID 17393709.

- Arena, Ross; Guazzi, Marco; Briggs, Paige D.; Cahalin, Lawrence P.; Myers, Jonathan; Kaminsky, Leonard A.; Forman, Daniel E.; Cipriano, Gerson; Borghi-Silva, Audrey; Babu, Abraham Samuel; Lavie, Carl J. (June 2013). "Promoting Health and Wellness in the Workplace: A Unique Opportunity to Establish Primary and Extended Secondary Cardiovascular Risk Reduction Programs". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 88 (6): 605–617. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.03.002. PMC 7304414. PMID 23726400. ProQuest 1371443680.

- "Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity | Healthy People 2020". www.healthypeople.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Worksite Physical Activity | Physical Activity | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- Carnethon, Mercedes; Whitsel, Laurie P.; Franklin, Barry A.; Kris-Etherton, Penny; Milani, Richard; Pratt, Charlotte A.; Wagner, Gregory R. (27 October 2009). "Worksite Wellness Programs for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 120 (17): 1725–1741. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192653. PMID 19794121. S2CID 11806217.

- Terry, Paul E.; Seaverson, Erin LD; Staufacker, Michael J.; Tanaka, Akiko (June 2011). "The Effectiveness of a Telephone-Based Tobacco Cessation Program Offered as Part of a Worksite Health Promotion Program". Population Health Management. 14 (3): 117–125. doi:10.1089/pop.2010.0026. PMID 21323463.

- "Physical Activity: Point-of-Decision Prompts to Encourage Use of Stairs | Healthy People 2020". www.healthypeople.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Fox, Lesley D.; Rejeski, W. Jack; Gauvin, Lise (May 2000). "Effects of Leadership Style and Group Dynamics on Enjoyment of Physical Activity". American Journal of Health Promotion. 14 (5): 277–283. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-14.5.277. PMID 11009853. S2CID 3270114.

- "Assessment Tools | Workplace Health Resources | Tools and Resources | Workplace Health Promotion | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- "Midcourse Review: LHIs | Healthy People 2020". www.healthypeople.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- Baicker, Katherine; Cutler, David; Song, Zirui (February 2010). "Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings". Health Affairs. 29 (2): 304–311. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626. PMID 20075081.

- Song, Zirui; Baicker, Katherine (16 April 2019). "Effect of a Workplace Wellness Program on Employee Health and Economic Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 321 (15): 1491–1501. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.3307. PMC 6484807. PMID 30990549.

- Abelson, Reed (16 April 2019). "Employee Wellness Programs Yield Little Benefit, Study Shows". The New York Times.

- "Preventing Chronic Disease: April 2009: 08_0206". www.cdc.gov.

- Knapper, Joseph T.; Ghasemzadeh, Nima; Khayata, Mohamed; Patel, Sulay P.; Quyyumi, Arshed A.; Mendis, Shanthi; Mensah, George A.; Taubert, Kathryn; Sperling, Laurence S. (August 2015). "Time to Change Our Focus". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 66 (8): 960–971. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.008. PMID 26293767.