Saltire

A saltire, also called Saint Andrew's Cross or the crux decussata,[1] is a heraldic symbol in the form of a diagonal cross. The word comes from the Middle French sautoir, Medieval Latin saltatoria ("stirrup").[2]

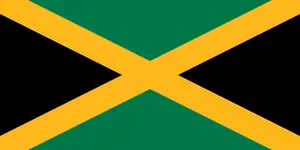

From its use as field sign, the saltire came to be used in a number of flags, in the 16th century for Scotland and Burgundy, in the 18th century also as the ensign of the Russian Navy, and for Ireland. Notable 19th-century usage includes some of the flags of the Confederate States of America. It is also used in the flag of Jamaica and on seals, and as a heraldic charge in coats of arms.

The term saltirewise or in saltire refers to heraldic charges arranged as a diagonal cross. The shield may also be divided per saltire, i.e. diagonally.

A warning sign in the shape of a saltire is also used to indicate the point at which a railway line intersects a road at a level crossing.

Heraldry and vexillology

The saltire is important both in heraldry, being found in many coats of arms, and in vexillology, being found as the dominant feature of multiple flags.

The saltire is one of the so-called ordinaries, geometric charges that span throughout (from edge to edge of) the shield. As suggested by the name saltire ("stirrup"; in French: sautoir, in German: Schragen), the ordinary in its early use was not intended as representing a Christian cross symbol. The association with Saint Andrew is a development of the 15th to 16th centuries. The Cross of Burgundy emblem originates in the 15th century, as a field sign, and as the Saint Andrew's Cross of Scotland was used in flags or banners (but not in coats of arms) from the 16th century, and used as naval ensign during the Age of Sail.

When two or more saltires appear, they are usually blazoned as couped (cut off). For example, contrast the single saltire in the arms granted to G. M. W. Anderson[lower-alpha 1]—with the three saltires couped in the coat of Kemble Greenwood.[lower-alpha 2]

Diminutive forms include the fillet saltire,[lower-alpha 3] usually considered half or less the width of the saltire, and the saltorel, a narrow or couped saltire.

A field (party) per saltire is divided into four areas by a saltire-shaped "cut". If two tinctures are specified, the first refers to the areas above (in chief) and below (in base) the crossing, and the second refers to the ones on either side (in the flanks).[lower-alpha 4] Otherwise, each of the four divisions may be blazoned separately.

The phrase in saltire or saltirewise is used in two ways:

- Two long narrow charges "in saltire" are placed to cross each other diagonally. Common forms include the crossed keys found in the arms of many entities associated with Saint Peter and paired arrows.[lower-alpha 5]

- When five or more compact charges are "in saltire", they are arranged with one in the center and the others along the arms of an invisible saltire.[lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7]

Division of the field per saltire was notably used by the Aragonese kings of Sicily beginning in the 14th century (Frederick the Simple), showing the pales of Aragon and the "Hohenstaufen" eagle (argent an eagle sable).

Scotland

The Flag of Scotland, called The Saltire or Saint Andrew's Cross, is a blue field with a white saltire. According to tradition, it represents Saint Andrew, who is supposed to have been crucified on a cross of that form (called a crux decussata) at Patras, Greece.

The Saint Andrew's Cross was worn as a badge on hats in Scotland, on the day of the feast of Saint Andrew.[1]

In the politics of Scotland, both the Scottish National Party and Scottish Conservative Party use stylised saltires as their party logos, deriving from the flag of Scotland.

Prior to the Union the Royal Scots Navy used a red ensign incorporating the St Andrew's Cross; this ensign is now sometimes flown as part of an unofficial civil ensign in Scottish waters. With its colours exchanged (and a lighter blue), the same design forms part of the arms and flag of Nova Scotia (whose name means "New Scotland").

Cross of Burgundy

The Cross of Burgundy, a form of the Saint Andrew's Cross, is used in numerous flags across Europe and the Americas. It was first used in the 15th century as an emblem by the Valois Dukes of Burgundy. The Duchy of Burgundy, forming a large part of eastern France and the Low Countries, was inherited by the House of Habsburg on the extinction of the Valois ducal line. The emblem was therefore assumed by the monarchs of Spain as a consequence of the Habsburgs bringing together, in the early 16th century, their Burgundian inheritance with the other extensive possessions they inherited throughout Europe and the Americas, including the crowns of Castile and Aragon. As a result, the Cross of Burgundy has appeared in a wide variety of flags connected with territories formerly part of the Burgundian or Habsburg inheritance. Examples of such diversity include the Spanish naval ensign (1506-1701), the flag of Carlism (a nineteenth century Spanish conservative movement), the flag of the Dutch capital of Amsterdam and municipality of Eijsden, the flag of Chuquisaca in Bolivia and the flags of Florida and Alabama in the United States.

Gascony

Gascony has not had any institutional unity since the 11th century, hence several flags are currently used in the territory. Legend says that this flag appeared in the time of Pope Clement III to gather the Gascons during the Third Crusade (12th century). That flag, sometimes called "Union Gascona" (Gascon Union), contains the St Andrew's cross, the patron saint of Bordeaux and the red color of English kingdom, which reigned over Gascony from 12th to mid-15th century.

In Tome 14 of the Grande Encyclopédie, published in France between 1886 and 1902 by Henri Lamirault, it says

during the hard times of the Hundred Years' War and the terrible struggles between the Armagnacs, representing the national party (white cross) and the Burgundians, allied to the English (red cross and red Saint Andrew's cross), the flag of the victorious English ends up gathering, in 1422, under Henri VI, on its field the white and red crosses of France and England, the white and red Saint Andrew's crosses of Guyenne and Burgundy.[10]

That saltire is also represented in the pattern of some talenquères in many bullrings in Gascony.[11]

Maritime flags

The naval ensign of the Imperial Russian (1696–1917) and Russian navies (1991–present) is a blue saltire on a white field.

The international maritime signal flag for M is a white saltire on a blue background, and indicates a stopped vessel. A red saltire on a white background denotes the letter V and the message "I require assistance".

Others

The flags of the Colombian archipelago of San Andrés and Providencia and the Spanish island of Tenerife also use a white saltire on a blue field. The Brazilian cities of Rio de Janeiro and Fortaleza also use a blue saltire on a white field, with their coats-of-arms at the hub.

Saltires are also seen in several other flags, including the flags of Grenada, Jamaica, Alabama, Florida, Jersey, Logroño, Vitoria, Amsterdam, Breda, Katwijk, Potchefstroom, The Bierzo and Valdivia, as well as the former Indian princely states of Khairpur, Rajkot and Jaora.

The design is also part of the Confederate Battle Flag and Naval Jack used during the American Civil War (see Flags of the Confederate States of America). Arthur L. Rogers, designer of the final version of the Confederate National flag, claimed that it was based on the saltire of Scotland.[12] The saltire is used on modern-day Southern U.S. state flags to honour the former Confederacy.[13]

Christian symbol

Anne Roes (1937) identifies a design consisting of two crossing diagonal lines in a rectangle, sometimes with four dots or balls in the four quarters, as an emblem or vexillum (standard) of Persepolis during the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC. Roes also finds the design in Argive vase painting, and still earlier in button seals of the Iranian Chalcolithic. Roes also notes the occurrence of a very similar if not identical vexillum which repeatedly occurs in Gaulish coins of c. the 2nd to 1st century BC, in a recurring design where it is held by a charioteer in front of his human-headed horse.[14] A large number of coins of this type (118 out of 152 items) forms part of the Les Sablons hoard of the 1st century BC, discovered in Le Mans between 1991 and 1997, associated with the Cenomani.[15]

The same design is found on coins of Christian Roman emperors of the 4th to 5th centuries (Constantius II, Valentinian, Jovian, Gratianus, Valens, Arcadius, Constantine III, Jovinus, Theodosius I, Eugenius and Theodosius II). The letter Χ (Chi) was from an early time used as a symbol for Christ (unrelated to the Christian cross symbol, which at the time was given a T-shape). The vexillum on imperial coins from the 4th century was sometimes shown as the Labarum, surmounted by or displaying the Chi-Rho monogram rather than just the crux decussata. The emblem of the crux decussata in a rectangle, sometimes with four dots or balls, re-appears in coins the Byzantine Empire, in the 9th to 10th centuries. Roes suggested that early Christians endorsed its solar symbolism as appropriate to Christ.[16]

![Reconstruction of Saltire pattern labarum per A.Roes[9]](../I/Labarum_(Saltire_Pattern).svg.png.webp) Reconstruction of Saltire pattern labarum per A.Roes[16]

Reconstruction of Saltire pattern labarum per A.Roes[16]

.png.webp) Coin of Theodosius I (393–395), with a vexillum displaying a crux decussata

Coin of Theodosius I (393–395), with a vexillum displaying a crux decussata%252C_zecca_di_costantinopoli_%CE%98_(theta).JPG.webp) Coin of Theodosius II (425–429), showing the emperor with globus cruciger and with the same vexillum

Coin of Theodosius II (425–429), showing the emperor with globus cruciger and with the same vexillum

The association with Saint Andrew develops in the late medieval period. The tradition according to which this saint was crucified on a decussate cross is not found in early hagiography. Depictions of Saint Andrew being crucified in this manner first appear in the 10th century, but do not become standard before the 17th century.[17] Reference to the saltire as "St Andrew's Cross" is made by the Parliament of Scotland (where Andrew had been adopted as patron saint) in 1385, in a decree to the effect that every Scottish and French soldier (fighting against the English under Richard II) "shall have a sign before and behind, namely a white St. Andrew's Cross".[18]

Saint Andrew martyred on a decussate cross (miniature from an East Anglian missal, c. 1320)

Saint Andrew martyred on a decussate cross (miniature from an East Anglian missal, c. 1320) Saint Andrew holding his cross on a Taler of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1688)

Saint Andrew holding his cross on a Taler of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1688)

Other

The diagonal cross (decussate cross) or X mark is called "saltire" in heraldic and vexillological contexts.

A black diagonal cross was used in an old European Union standard as the hazard symbol for irritants (Xi) or harmful chemicals (Xn). It indicated a hazard less severe than skull and crossbones, used for poisons, or the corrosive sign.

The Maria Theresa thaler has a Roman numeral ten to symbolize the 1750 debasement of the coinage, from 9 to 10 thalers to the Vienna mark (a weight of silver).

A diagonal cross known as "crossbuck" is used as the conventional road sign used to indicate the point at which a railway line intersects a road at a level crossing, called a in this context. A white diagonal cross on a blue background (or black on yellow for temporary signs) is displayed in UK railway signalling as a "cancelling indicator" for the Automatic Warning System (AWS), informing the driver that the received warning can be disregarded.

In Cameroon, a red "X" placed on illegally constructed buildings scheduled for demolition is occasionally referred to as a "St Andrew's Cross". It is usually accompanied by the letters "A.D." ("à détruire"—French for "to be demolished") and a date or deadline. During a campaign of urban renewal by the Yaoundé Urban Council in Cameroon, the cross was popularly referred to as "Tsimi's Cross" after the Government Delegate to the council, Gilbert Tsimi Evouna.[19]

In traditional timber framing a pair of crossing braces is sometimes called a saltire or a St. Andrew's Cross.[20] Half-timbering, particularly in France and Germany, has patterns of framing members forming many different symbols known as ornamental bracing.[21]

The saltire cross, X-cross, X-frame, or Saint Andrew's cross is a common piece of equipment in BDSM dungeons. It is erotic furniture that typically provides restraining points for ankles, wrists, and waist. When secured to an X-cross, the subject is restrained in a standing spreadeagle position.

Unicode encoded various decussate crosses under the name of saltire, they are U+2613 ☓ SALTIRE, U+1F7A8 🞨 THIN SALTIRE, U+1F7A9 🞩 LIGHT SALTIRE, U+1F7AA 🞪 MEDIUM SALTIRE, U+1F7AB 🞫 BOLD SALTIRE, U+1F7AC 🞬 HEAVY SALTIRE, U+1F7AD 🞭 VERY HEAVY SALTIRE and U+1F7AE 🞮 EXTREMELY HEAVY SALTIRE.

Gallery

Coats of arms

Gules a saltire argent (Neville)

Gules a saltire argent (Neville)

Argent a saltire azure (Katwijk)

Argent a saltire azure (Katwijk) Per saltire azure and argent, a saltire gules (Gage of Hengrave)

Per saltire azure and argent, a saltire gules (Gage of Hengrave)_Escutcheon.png.webp) Argent on a saltire engrailed sable nine annulets of the field (Earl of Scarsdale)

Argent on a saltire engrailed sable nine annulets of the field (Earl of Scarsdale)![Quarterly 1st & 4th: Barry of six [seven] vair and gules; 2nd & 3rd: Gules, a saltire vair (Henry Beaumont of Devon, d.1591)](../I/BeaumontWillingtonArmsGittishamDevon.JPG.webp) Quarterly 1st & 4th: Barry of six [seven] vair and gules; 2nd & 3rd: Gules, a saltire vair (Henry Beaumont of Devon, d.1591)

Quarterly 1st & 4th: Barry of six [seven] vair and gules; 2nd & 3rd: Gules, a saltire vair (Henry Beaumont of Devon, d.1591).svg.png.webp) Argent a saltire floretty gules (Busséol)

Argent a saltire floretty gules (Busséol) Gules a fillet saltire couped argent above a wheel of the same (Klein-Winternheim)

Gules a fillet saltire couped argent above a wheel of the same (Klein-Winternheim) Coat of arms of the San Andrés Archipelago

Coat of arms of the San Andrés Archipelago

- saltirewise

.svg.png.webp) Gules two keys in saltire argent and or (Coats of arms of the Holy See and Vatican City)

Gules two keys in saltire argent and or (Coats of arms of the Holy See and Vatican City) Gules a cross saltire and orle of chains linked together or, in the fess point an emerald vert (Kingdom of Navarre)

Gules a cross saltire and orle of chains linked together or, in the fess point an emerald vert (Kingdom of Navarre) Gules two keys argent saltirewise (Papal coat of arms for Pope Nicholas V, 1447)

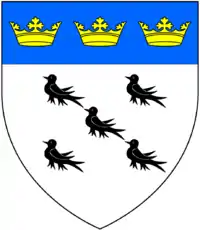

Gules two keys argent saltirewise (Papal coat of arms for Pope Nicholas V, 1447) Argent five martlets saltirewise sable on a chief azure three ducal crowns or (Bodley)

Argent five martlets saltirewise sable on a chief azure three ducal crowns or (Bodley) Vert bordure or a caduceus argent and or and a cornucopia or with fruits and vegetables proper saltirewise (Coat of arms of Kharkiv, Ukraine)

Vert bordure or a caduceus argent and or and a cornucopia or with fruits and vegetables proper saltirewise (Coat of arms of Kharkiv, Ukraine) Vert bordure or a torch and a caduceus or saltirewise (Federal Customs Service of Russia)

Vert bordure or a torch and a caduceus or saltirewise (Federal Customs Service of Russia) Argent two keys sable saltirewise under a cross pattée or (Lesser coat of arms of Riga, Latvia)

Argent two keys sable saltirewise under a cross pattée or (Lesser coat of arms of Riga, Latvia)

- in supporters

Papal coat of arms for Pope Innocent VIII with the Keys of Peter saltirewise (Wernigerode Armorial, c. 1490)

Papal coat of arms for Pope Innocent VIII with the Keys of Peter saltirewise (Wernigerode Armorial, c. 1490)-Common_Version_of_the_Colours.svg.png.webp) Royal Coat of Arms of Spain (1700–1761)[23]

Royal Coat of Arms of Spain (1700–1761)[23]-Version_of_the_Colours.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms of Spain (1874–1931)[23]

Coat of arms of Spain (1874–1931)[23] Coat of arms of the House of Braganza.

Coat of arms of the House of Braganza.

- other

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms of Barbados with Sugar Canes held saltirewise.

Coat of arms of Barbados with Sugar Canes held saltirewise.

Flags

.svg.png.webp) Vatican City's flag (Flag of Vatican City)

Vatican City's flag (Flag of Vatican City) Saint Alban's flag (13th century)

Saint Alban's flag (13th century) Naval flag of the Kingdom of Sicily (after Guillem Soler c. 1380), inheriting the per saltire division from the royal coat of arms.

Naval flag of the Kingdom of Sicily (after Guillem Soler c. 1380), inheriting the per saltire division from the royal coat of arms..png.webp) Flag of Scotland (c. 1507)[24]

Flag of Scotland (c. 1507)[24]

Cross of Burgundy Flag, Spanish Empire (16th century)

Cross of Burgundy Flag, Spanish Empire (16th century)

Tercio de la Liga (1571)

Tercio de la Liga (1571) Saint Patrick's Flag (1783)

Saint Patrick's Flag (1783).svg.png.webp) Union Jack (1606)

Union Jack (1606) Union Jack in Scotland (1606)

Union Jack in Scotland (1606) Union Jack (1801)

Union Jack (1801) Unknown Tercio flag (appears near commander Ambrogio Spinola in the painting "The Surrender of Breda" of Diego Velázquez) (1621)

Unknown Tercio flag (appears near commander Ambrogio Spinola in the painting "The Surrender of Breda" of Diego Velázquez) (1621) Tercio de Alburquerque (1643)

Tercio de Alburquerque (1643) Tercio Morados Viejos (1670)

Tercio Morados Viejos (1670) Tercio Amarillos Viejos (1680)

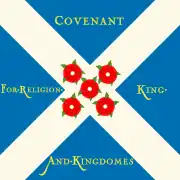

Tercio Amarillos Viejos (1680) Scottish Covenanter flag (17th century)

Scottish Covenanter flag (17th century) Flag of Argyll's Rising (1685)

Flag of Argyll's Rising (1685)

Jack of the Russian Navy (1992)

Jack of the Russian Navy (1992) Flag of Congress Poland (1815)

Flag of Congress Poland (1815) Flag of Nova Scotia (1858)

Flag of Nova Scotia (1858) Confederate Army of Northern Virginia battle flag (1863–1865)

Confederate Army of Northern Virginia battle flag (1863–1865).svg.png.webp)

Flag of Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai International Settlement (1869 – c. 1917)

Flag of Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai International Settlement (1869 – c. 1917) Flag of Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai International Settlement (c. 1917 – 1943)

Flag of Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai International Settlement (c. 1917 – 1943)

.svg.png.webp) Flag of Peru (1821–1825)

Flag of Peru (1821–1825) Flag of Rio de Janeiro (1908)

Flag of Rio de Janeiro (1908)_-_variant.svg.png.webp) Flag of the Empire of China (1915–1916)

Flag of the Empire of China (1915–1916) White Army General Markov's Regiment flag (1917–1922)

White Army General Markov's Regiment flag (1917–1922) Naval flag of the Far Eastern Republic (1921–1922)

Naval flag of the Far Eastern Republic (1921–1922) Jack of the Estonian Navy (1926)

Jack of the Estonian Navy (1926) Flag of Minister of Finance of the Republic of China (1929)

Flag of Minister of Finance of the Republic of China (1929) Flag of Fortaleza (1958)

Flag of Fortaleza (1958) Flag of Jamaica (1962)

Flag of Jamaica (1962)_1970.svg.png.webp) Flag of Katwijk (1970)

Flag of Katwijk (1970) Banner of Kraków (2004)

Banner of Kraków (2004) Flag of Grenada (1974)

Flag of Grenada (1974) Flag of Amsterdam (1975)

Flag of Amsterdam (1975) Flag of the Basque Country (the Ikurrina) (1978)

Flag of the Basque Country (the Ikurrina) (1978)

Flag of Jersey (1981)

Flag of Jersey (1981) Flag of Burundi (1982)

Flag of Burundi (1982) Flag of Tenerife (1989)

Flag of Tenerife (1989) Flag of the Federal Customs Service of Russia (1994)

Flag of the Federal Customs Service of Russia (1994) Ceremonial ensign of the Coast Guard of Georgia (1999)

Ceremonial ensign of the Coast Guard of Georgia (1999) Battle ensign of the Coast Guard of Georgia (2004)

Battle ensign of the Coast Guard of Georgia (2004) Naval Ensign of Georgia (2004–2009)

Naval Ensign of Georgia (2004–2009) Flag of the Russian Coast Guard (2008)

Flag of the Russian Coast Guard (2008) Flag of Arkhangelsk Oblast (2009)

Flag of Arkhangelsk Oblast (2009) Flag of Katwijk (2009)

Flag of Katwijk (2009) Flag of Novorossiya (2014)

Flag of Novorossiya (2014) Flag of Ruhnu Parish, Estonia (2015)

Flag of Ruhnu Parish, Estonia (2015) Flag of Vladivostok (2016)

Flag of Vladivostok (2016)

- International Code of Signals

- United States

Flag of Alabama (1895)

Flag of Alabama (1895) Flag of Florida (1868, 1900)

Flag of Florida (1868, 1900).svg.png.webp) Flag of Georgia (1956–2001)

Flag of Georgia (1956–2001).svg.png.webp) Flag of Mississippi (1894–2020)

Flag of Mississippi (1894–2020)

Military insignia

Spanish Air Force fin flash

Spanish Air Force fin flash.svg.png.webp) Bulgarian Air Force roundel (1941–1944)

Bulgarian Air Force roundel (1941–1944).svg.png.webp) Bayonets in saltire create Roman numeral X for the US Army's 10th Mountain Division.

Bayonets in saltire create Roman numeral X for the US Army's 10th Mountain Division.

See also

Notes

- Or on a saltire engrailed Azure two quill pens in saltire Argent enfiling a Loyalist military coronet Or[4]

- Sable a chevron Erminois cotised between three saltires couped Or[5]

- The coat of the South African National Cultural and Open-air Museum: Or; an ogress charged with a fillet saltire surmounted by an eight spoked wheel or, and ensigned of a billet sable; a chief nowy gabled, Sable

- The coat of the Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council: Per saltire Vert and Or four Fers de Moline counterchanged in fess point a Fountain.[6]

- Suffolk County Council's Gules a Base barry wavy enarched Argent and Azure issuant therefrom a Sunburst in chief two Ancient Crowns enfiled by a pair of Arrows in saltire points downwards all Or[7]

- Winchester City Council: Gules five castles triple towered, in saltire, argent, masoned proper the portcullis of each part-raised, or, and on either side of the castle in fess point a lion passant guardant that to the dexter contourny Or[8]

- The arms of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America: Argent; a quarter azure charged with nine cross crosslets in saltire argent, overall a cross gules[9]

References

- "Crux decussata". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- Heraldic use 13th century (attested 1235, Huon de Méry, Tournoiemenz Antecrist, v. 654). In 1352 also of a particular form of stirrup (Comput. Steph. de la Fontaine argent, du Cange s.v. "saltatoria"). 15th-century use in the sense of a barrier of wooden pegs arranged crosswise, preventing the passage of livestock that can still be jumped by people. "sautoire" in TLFi; see also "saltire" at etymonline.com.

- Berhard Peter, Die Wappen des Hauses Oettingen (2010–2016).

- "Anderson, George Milton William [Individual]". Archive.gg.ca. 2005-07-28. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- "Greenwood, Kemble [Individual]". Archive.gg.ca. 2005-07-28. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- "Civic Heraldry Of England And Wales-West Midlands". Civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- "Civic Heraldry Of England And Wales – East Anglia And Essex Area". Civicheraldry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-08-28. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- "Civic Heraldry Of England And Wales - Cornwall And Wessex Area". Civicheraldry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 2012-09-09.

- "Logos, Shields & Graphics".

- La grande encyclopédie : Inventaire raisonné des sciences, des lettres et des arts. Tome 14 / Par une société de savants et de gens de lettres ; sous la dir. De MM. Berthelot,... Hartwig Derenbourg,... F.-Camille Dreyfus,... A. Giry,... [et al.].

- @Pickwicq (21 February 2016). "Amandine derrière la talenquère pour pentecôte à Samadet 2015" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Coski, John M. (2005). The Confederate Battle Flag: America's Most Embattled Emblem. United States of America: First Harvard University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-674-01722-1.

- Coski, John M. (2005). The Confederate Battle Flag: America's Most Embattled Emblem. United States of America: First Harvard University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-674-01722-1.

- Roes (1937), footnote 15, citing Henri de La Tour, Atlas de monnaies gauloises (1892), plates xxi, xxiii, coins of the Aulerci Diablintes, Aulerci Cenomani and Osismii.

- Trésors monétaires, volume XXIV, BNF, 2011.

- Roes, Anne (1937). "An Iranian standard used as a Christian symbol". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 57 (2): 248–51. doi:10.2307/627151. JSTOR 627151. S2CID 162699148.

- Cudith Calvert, "The Iconography of the St. Andrew Auckland Cross", The Art Bulletin 66.4 (December 1984:543–555) p. 545, note 12, citing Louis Réau, Iconographie de l'art chrétien III.1 (Paris) 1958:79.

- The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, K.M. Brown et al. (eds.), St Andrews (2007-2019), 1385/6/4 "ordinance made in council concerning the French army": Item, que tout homme, Francois et Escot, ait un signe devant et derrere cest assavoir une croiz blanche Saint Andrieu et se son jacque soit blanc ou sa cote blanche il portera la dicte croiz blanche en une piece de drap noir ronde ou quarree.

- "Célestin Obama. Tsimi Evouna s'attaque aux édifices publics, Le Messager, 23 Sept 2008". Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- Hansen, Hans Jürgen, and Arne Berg. Architecture in wood; a history of wood building and its techniques in Europe and North America. New York: Viking Press, 1971. Print.

- Rudolf Huber and Renate Rieth, Glossarium Artis, 10, Holzbaukunst - Architecture en Bois - Architecture in Wood. Munich, Germany: Saur. 1997. 55. ISBN 3-598-10461-8

- "CIVIC HERALDRY OF ENGLAND AND WALES - HERTFORDSHIRE". www.civicheraldry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- As a naval flag for the carrack Great Michael. As square flag carried by heraldic supporters c. 1542. National Library of Scotland (1542). "Plate from the Lindsay Armorial". Scran. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Saltier". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Saltier". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

External links

Media related to Saint Andrew's crosses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Saint Andrew's crosses at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)