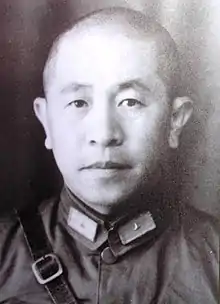

Ye Jizhuang

Ye Jizhuang (Chinese: 叶季壮; Wade–Giles: Yeh Chi-chuang; 1893–1967) was a Chinese Communist revolutionary and politician nicknamed the "Red Manager".[1] He served as the logistics head of the Red Army during the Long March and of the Yan'an Communist headquarters during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In 1945, he was among the first three officers awarded the rank of lieutenant general by the Chinese Communist Party, together with Peng Zhen and Chen Yun. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, he served as the country's first Minister of Trade and then Minister of Foreign Trade until his death in 1967.

Ye Jizhuang | |

|---|---|

| 叶季壮 | |

| |

| 1st Minister of Trade | |

| In office October 1949 – August 1952 | |

| Preceded by | New position |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Minister of Foreign Trade) |

| 1st Minister of Foreign Trade | |

| In office August 1952 – June 1967 | |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Minister of Trade) |

| Succeeded by | Lin Haiyun (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1893 Xinxing County, Guangdong, China |

| Died | 27 June 1967 (aged 73–74) Beijing, China |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party |

| Spouse | Ma Luzhen |

| Alma mater | Guangdong Provincial Law and Politics School |

Early life

Ye was born in 1893 into a poor peasant family in Xinxing County, Guangdong, Qing dynasty China. He was admitted to Guangdong Provincial Law and Politics School in 1912, and worked in the local governments of Jiangmen and Xinxing after graduating in 1914. In June 1925, he organized the Jiangmen General Union and participated in the Great Canton–Hong Kong strike. He joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at the end of that year.[1][2]

Red Army and Long March

After Chiang Kai-shek turned against the Communists at the Shanghai massacre in 1927, Ye participated in the Guangzhou Uprising (1927) and the Baise Uprising (1929) led by Deng Xiaoping. He was a co-founder of the Seventh Army of the Chinese Red Army and served as Director of its Political Department. After the Seventh Army reached the Jiangxi Soviet, the central Communist base, he was appointed Director of the Logistics Department of the Red Army.[1]

When the Long March began in October 1934, Ye was in charge of logistics for the Red Army under extremely difficult conditions, as the Communist force was under constant attacks from the Kuomintang and its allies.[1] In his memoirs, Yang Shangkun, who later served as President of the People's Republic of China, recalls a feast Ye prepared for the officers in Hadapu, Gansu, after the army starved for days following the Battle of Lazikou. He remembered that Ye specifically asked everybody not to overeat, as it could be dangerous immediately after starvation.[1]

After the Red Army reached Yan'an a year later, Ye became the logistics head of the new Communist base there, and of the Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. He worked on developing agriculture, manufacturing, foreign trade, and medical care for the Yan'an base, which was under economic blockade from the Kuomintang government in Chongqing.[1]

Northeast China

After the surrender of Japan in 1945, the former Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China became a major area of contention between the Communists and the Kuomintang. The CCP Central Committee sent a six-person team to Shenyang to negotiate with the Soviet Union which had taken over the region from Japan. To facilitate their negotiation with Soviet commanders who held military ranks, the CCP awarded Peng Zhen, Chen Yun and Ye the rank of lieutenant general,[1] Wu Xiuquan the rank of major general, and two other officers the rank of colonel. It was the first time the CCP issued military ranks.[1] Ye served as Minister of Finance and Minister of Commerce in the Northeast People's Government, the transitional government in the Northeast in preparation for the establishment of the People's Republic of China.[1]

People's Republic of China

With the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in October 1949, Ye was appointed the country's first Minister of Trade. In August 1952, the ministry's foreign trade division was expanded into the Ministry of Foreign Trade, and Ye became its inaugural minister. It was a large ministry with many layers of organization, which served not only commercial, but also diplomatic functions. Ye served as head of the important ministry until his death in 1967.[3] A major task of his was to circumvent the trade embargo against the PRC by the United States and its allies. Under the leadership of Zhou Enlai, he developed trade relations with Asian and African countries and signed China's first trade deal with Ceylon.[1][2] After the Sino-Soviet split, Ye played a key role in China's export drive in order to repay Soviet debts[1] and finance grain purchases from abroad.[4]

Ye suffered a stroke in 1961 when he was on an official trip in Guangzhou.[1] He became incapacitated by another stroke in 1964, and his deputy Lin Haiyun took over as acting minister in 1965.[4][3] Already in very poor health, Ye came under persecution when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966. He was pressured to incriminate his former superior Deng Xiaoping, but refused to do so. As he was bedridden, his doctors prevented the Red Guards from taking him to struggle sessions, and his wife Ma Luzhen (马禄祯) was taken in his place.[1]

Ye died on 27 June 1967 at the age of 74.[1] He was politically rehabilitated after the end of the Cultural Revolution. He is now recognized as an essential figure in the logistics of the People's Liberation Army during wartime, and the management of foreign trade of the early PRC. He is honoured as the "Red Manager" of the Communist Party.[1][2]

References

- Song, Fengying (2011-03-23). ""红色管家"叶季壮". People's Daily. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- "Ye Jizhuang". PRC Ministry of Commerce. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Gene T. Hsiao (1977). The Foreign Trade of China: Policy, Law, and Practice. University of California Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-520-03257-6.

- Chad J. Mitcham (2005). China's Economic Relations with the West and Japan, 1949-79: Grain, Trade and Diplomacy. Psychology Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-415-31481-7.