Yokohama

Yokohama (Japanese: 横浜, pronounced [jokohama] ⓘ) is the second-largest city in Japan by population[1] and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of Tokyo, in the Kantō region of the main island of Honshu. Yokohama is also the major economic, cultural, and commercial hub of the Greater Tokyo Area along the Keihin Industrial Zone.

Yokohama

横浜市 | |

|---|---|

| City of Yokohama | |

From top, left to right: Minato Mirai 21 at dusk, Nippon Maru Memorial Park, Yokohama Chinatown, Motomachi Shopping Street, Sankei-en, Harbor View Park, Yokohama Marine Tower viewed from Yamashita Park and Ōsanbashi Pier | |

Flag  Seal | |

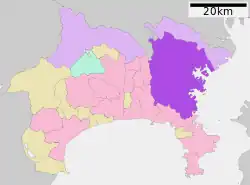

Map of Kanagawa Prefecture with Yokohama highlighted in purple | |

Yokohama  Yokohama Yokohama (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 35°26′39″N 139°38′17″E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Kanagawa Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Takeharu Yamanaka |

| Area | |

| • Total | 437.38 km2 (168.87 sq mi) |

| Population (January 1, 2023) | |

| • Total | 3,769,595 |

| • Density | 8,606/km2 (22,290/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| – Tree | Camellia, Chinquapin, Sangoju Sasanqua, Ginkgo, Zelkova |

| – Flower | Dahlia Rose |

| Address | 1-1 Minato-chō, Naka-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa-ken 231-0017 |

| Website | www |

| Yokohama | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Hiragana | よこはま | ||||

| Katakana | ヨコハマ | ||||

| Kyūjitai | 橫濱 | ||||

| Shinjitai | 横浜 | ||||

| |||||

Yokohama was one of the cities to open for trade with the West following the 1859 end of the policy of seclusion and has since been known as a cosmopolitan port city, after Kobe opened in 1853. Yokohama is the home of many Japan's firsts in the Meiji period, including the first foreign trading port and Chinatown (1859), European-style sport venues (1860s), English-language newspaper (1861), confectionery and beer manufacturing (1865), daily newspaper (1870), gas-powered street lamps (1870s), railway station (1872), and power plant (1882). Yokohama developed rapidly as Japan's prominent port city following the end of Japan's relative isolation in the mid-19th century and is today one of its major ports along with Kobe, Osaka, Nagoya, Fukuoka, Tokyo and Chiba.

Yokohama is the largest port city and high tech industrial hub in the Greater Tokyo Area and the Kantō region. The city proper is headquarters to companies such as Isuzu, Nissan, JVCKenwood, Keikyu, Koei Tecmo, Sotetsu, Salesforce Japan and Bank of Yokohama. Famous landmarks in Yokohama include Minato Mirai 21, Nippon Maru Memorial Park, Yokohama Chinatown, Motomachi Shopping Street, Yokohama Marine Tower, Yamashita Park, and Ōsanbashi Pier.

Etymology

Yokohama (横浜) means "horizontal beach".[2] The current area surrounded by Maita Park, the Ōoka River and the Nakamura River have been a gulf divided by a sandbar from the open sea. This sandbar was the original Yokohama fishing village. Since the sandbar protruded perpendicularly from the land, or horizontally when viewed from the sea, it was called a "horizontal beach".[3]

History

Opening of the Treaty Port (1859–1868)

Before the Western foreigners arrived, Yokohama was a small fishing village up to the end of the feudal Edo period, when Japan held a policy of national seclusion, having little contact with foreigners.[4] A major turning point in Japanese history happened in 1853–54, when Commodore Matthew Perry arrived just south of Yokohama with a fleet of American warships, demanding that Japan open several ports for commerce, and the Tokugawa shogunate agreed by signing the Treaty of Peace and Amity.[5]

It was initially agreed that one of the ports to be opened to foreign ships would be the bustling town of Kanagawa-juku (in what is now Kanagawa Ward) on the Tōkaidō, a strategic highway that linked Edo to Kyoto and Osaka. However, the Tokugawa shogunate decided that Kanagawa-juku was too close to the Tōkaidō for comfort, and port facilities were instead built across the inlet in the sleepy fishing village of Yokohama. The Port of Yokohama was officially opened on June 2, 1859.[6]

Yokohama quickly became the base of foreign trade in Japan. Foreigners initially occupied the low-lying district of the city called Kannai, residential districts later expanding as the settlement grew to incorporate much of the elevated Yamate district overlooking the city, commonly referred to by English-speaking residents as The Bluff. Under pressure from United States and United Kingdom officials, the Tokugawa government built a commercial sex district which opened on November 10, 1859, with 6 brothels and 200 indentured sex workers.[7]: 68 The area of Yokohama with the highest concentration of brothels was known as Bloodtown.[7]: 67

Kannai, the foreign trade and commercial district (literally, inside the barrier), was surrounded by a moat, foreign residents enjoying extraterritorial status both within and outside the compound. Interactions with the local population, particularly young samurai, outside the settlement inevitably caused problems; the Namamugi Incident, one of the events that preceded the downfall of the shogunate, took place in what is now Tsurumi Ward in 1862, and prompted the Bombardment of Kagoshima in 1863.

To protect British commercial and diplomatic interests in Yokohama a military garrison was established in 1862. With the growth in trade increasing numbers of Chinese also came to settle in the city.[8] Yokohama was the scene of many notable firsts for Japan including the growing acceptance of western fashion, photography by pioneers such as Felice Beato, Japan's first English language newspaper, the Japan Herald published in 1861 and in 1865 the first ice cream confectionery and beer to be produced in Japan.[9] Recreational sports introduced to Japan by foreign residents in Yokohama included European style horse racing in 1862, cricket in 1863[10] and rugby union in 1866. A great fire destroyed much of the foreign settlement on November 26, 1866, and smallpox was a recurrent public health hazard, but the city continued to grow rapidly – attracting foreigners and Japanese alike.

- Gallery

Landing of Commodore Perry and men to meet the Imperial commissioners at Yokohama, 14 July 1853

Landing of Commodore Perry and men to meet the Imperial commissioners at Yokohama, 14 July 1853 Foreign ships in Yokohama harbor in 1861

Foreign ships in Yokohama harbor in 1861 A foreign trading house in Yokohama in 1861

A foreign trading house in Yokohama in 1861

Meiji and Taisho Periods (1868–1923)

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the port was developed for trading silk, the main trading partner being Great Britain. Western influence and technological transfer contributed to the establishment of Japan's first daily newspaper (1870), first gas-powered street lamps (1872) and Japan's first railway constructed in the same year to connect Yokohama to Shinagawa and Shinbashi in Tokyo. In 1872 Jules Verne portrayed Yokohama, which he had never visited, in an episode of his widely read novel Around the World in Eighty Days, capturing the atmosphere of the fast-developing, internationally oriented Japanese city.

In 1887, a British merchant, Samuel Cocking, built the city's first power plant. At first for his own use, this coal power plant became the basis for the Yokohama Cooperative Electric Light Company. The city was officially incorporated on April 1, 1889.[11] By the time the extraterritoriality of foreigner areas was abolished in 1899, Yokohama was the most international city in Japan, with foreigner areas stretching from Kannai to the Bluff area and the large Yokohama Chinatown.

The early 20th century was marked by rapid growth of industry. Entrepreneurs built factories along reclaimed land to the north of the city toward Kawasaki, which eventually grew to be the Keihin Industrial Area. The growth of Japanese industry brought affluence, and many wealthy trading families constructed sprawling residences there, while the rapid influx of population from Japan and Korea also led to the formation of Kojiki-Yato, then the largest slum in Japan.

- Gallery

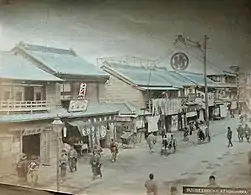

Street scene c. 1880

Street scene c. 1880 Yokohama c. 1880

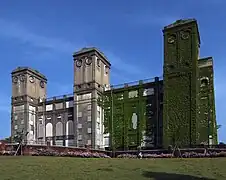

Yokohama c. 1880 Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse was built in 1913.

Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse was built in 1913.

Great Kantō earthquake and the Second World War (1923–1945)

- Gallery

Crown Prince Hirohito (later Emperor) visited Yokohama immediately after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

Crown Prince Hirohito (later Emperor) visited Yokohama immediately after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. View of Yokohama after the bombing in 1945

View of Yokohama after the bombing in 1945

Much of Yokohama was destroyed on September 1, 1923, by the Great Kantō earthquake. The Yokohama police reported casualties at 30,771 dead and 47,908 injured, out of a pre-earthquake population of 434,170.[12] Fuelled by rumors of rebellion and sabotage, vigilante mobs thereupon murdered many Koreans in the Kojiki-yato slum.[13] Many people believed that Koreans used black magic to cause the earthquake. Martial law was in place until November 19. Rubble from the quake was used to reclaim land for parks, the most famous being the Yamashita Park on the waterfront which opened in 1930.

Yokohama was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again by U.S. air raids during World War II. The first bombing was in the April 18, 1942 Doolittle Raid. An estimated 7,000–8,000 people were killed in a single morning on May 29, 1945, in what is now known as the Great Yokohama Air Raid, when B-29s firebombed the city and in just one hour and nine minutes, reducing 42% of it to rubble.[11]

Postwar growth and development

During the American occupation, Yokohama was a major transshipment base for American supplies and personnel, especially during the Korean War. After the occupation, most local U.S. naval activity moved from Yokohama to an American base in nearby Yokosuka.

Four years after the Treaty of San Francisco signed, the city was designated by government ordinance on September 1, 1956. The city's tram and trolleybus system was abolished in 1972, the same year as the opening of the first line of Yokohama Municipal Subway. Construction of Minato Mirai 21 ("Port Future 21"), a major urban development project on reclaimed land started in 1983, nicknamed the "Philadelphia and Boston of the Orient" was compared to Center City, Philadelphia and Downtown Boston located in the East Coast of the United States. Minato Mirai 21 hosted the Yokohama Exotic Showcase in 1989, which saw the first public operation of maglev trains in Japan and the opening of Cosmo Clock 21, then the tallest Ferris wheel in the world. The 860-metre-long (2,820 ft) Yokohama Bay Bridge opened in the same year. In 1993, Minato Mirai 21 saw the opening of the Yokohama Landmark Tower, the second-tallest building in Japan.

The 2002 FIFA World Cup final was held in June at the International Stadium Yokohama. In 2009, the city marked the 150th anniversary of the opening of the port and the 120th anniversary of the commencement of the City Administration. An early part in the commemoration project incorporated the Fourth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD IV), which was held in Yokohama in May 2008. In November 2010, Yokohama hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting.

- Gallery

In 1951, during the Korean War, a troopship, the USS General George M. Randall (AP-115), departs Yokohama, repatriating war dead to the U.S.

In 1951, during the Korean War, a troopship, the USS General George M. Randall (AP-115), departs Yokohama, repatriating war dead to the U.S. Yokohama Landmark Tower, Japan's second-tallest building, was built in 1993.

Yokohama Landmark Tower, Japan's second-tallest building, was built in 1993. The Minato Mirai 21 project, also known as the "Philadelphia and Boston of the Orient", started in 1983.

The Minato Mirai 21 project, also known as the "Philadelphia and Boston of the Orient", started in 1983.

Geography

Topography

Yokohama has a total area of 437.38 km2 (168.87 sq mi) at an elevation of 5 metres (16 ft) above sea level. It is the capital of Kanagawa Prefecture, bordered to the east by Tokyo Bay and located in the middle of the Kantō plain. The city is surrounded by hills and the characteristic mountain system of the island of Honshū, so its growth has been limited and it has had to gain ground from the sea. This also affects the population density, one of the highest in Japan with 8,500 inhabitants per km2.

The highest points within the urban boundary are Omaruyama (156 m [512 ft]) and Mount Enkaizan (153 m [502 ft]). The main river is the Tsurumi River, which begins in the Tama Hills and empties into the Pacific Ocean.[14]

These municipalities surround Yokohama: Kawasaki, Yokosuka, Zushi, Kamakura, Fujisawa, Yamato, Machida.

Geology

The city is very prone to natural phenomena such as earthquakes and tropical cyclones because the island of Honshū has a high level of seismic activity, being in the middle of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

Most seismic movements are of low intensity and are generally not perceived by people. However, Yokohama has experienced two major tremors that reflect the evolution of Earthquake engineering: the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake devastated the city and caused more than 100,000 fatalities throughout the region,[15] while the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, with its epicenter on the east coast, was felt in the locality but only material damage was lamented because most buildings were already prepared to withstand them.[16]

Climate

Yokohama features a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa) with hot, humid summers and chilly winters.[17] Weatherwise, Yokohama has a pattern of rain, clouds and sun, although in winter, it is surprisingly sunny, more so than Southern Spain. Winter temperatures rarely drop below freezing, while summer can seem quite warm, because of the effects of humidity.[18] The coldest temperature was on 24 January 1927 when −8.2 °C (17.2 °F) was reached, whilst the hottest day was 11 August 2013 at 37.4 °C (99.3 °F). The highest monthly rainfall was in October 2004 with 761.5 millimetres (30.0 in), closely followed by July 1941 with 753.4 millimetres (29.66 in), whilst December and January have recorded no measurable precipitation three times each.

| Climate data for Yokohama (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1896−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.3 (88.3) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

36.2 (97.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

37.4 (99.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.3 (75.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.3 (55.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 64.7 (2.55) |

64.7 (2.55) |

139.5 (5.49) |

143.1 (5.63) |

152.6 (6.01) |

188.8 (7.43) |

182.5 (7.19) |

139.0 (5.47) |

241.5 (9.51) |

240.4 (9.46) |

107.6 (4.24) |

66.4 (2.61) |

1,730.8 (68.14) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 4 (1.6) |

4 (1.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

9 (3.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 5.7 | 6.3 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 13.5 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 6.2 | 118.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 53 | 54 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 76 | 71 | 65 | 57 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.7 | 167.2 | 168.8 | 181.2 | 187.4 | 135.9 | 170.9 | 206.4 | 141.2 | 137.3 | 151.1 | 178.1 | 2,018.3 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[19] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Yokohama night view (2014)

Yokohama night view (2014) View from Mosaic Mall Kohoku (2015)

View from Mosaic Mall Kohoku (2015).jpg.webp) View from the Yokohama Bay Bridge (2007)

View from the Yokohama Bay Bridge (2007).jpg.webp) View from Hikawa Maru (2014)

View from Hikawa Maru (2014)

Demographics

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 64,602[20] | — |

| 1880 | 72,630 | +12.4% |

| 1890 | 132,627 | +82.6% |

| 1900 | 196,653 | +48.3% |

| 1910 | 403,303 | +105.1% |

| 1920 | 422,942 | +4.9% |

| 1925 | 405,888 | −4.0% |

| 1930 | 620,306 | +52.8% |

| 1935 | 704,290 | +13.5% |

| 1940 | 968,091 | +37.5% |

| 1945 | 814,379 | −15.9% |

| 1950 | 951,188 | +16.8% |

| 1955 | 1,143,687 | +20.2% |

| 1960 | 1,375,710 | +20.3% |

| 1965 | 1,788,915 | +30.0% |

| 1970 | 2,238,264 | +25.1% |

| 1975 | 2,621,771 | +17.1% |

| 1980 | 2,773,674 | +5.8% |

| 1985 | 2,992,926 | +7.9% |

| 1990 | 3,220,331 | +7.6% |

| 1995 | 3,307,136 | +2.7% |

| 2000 | 3,426,651 | +3.6% |

| 2005 | 3,579,628 | +4.5% |

| 2010 | 3,688,773 | +3.0% |

| 2015 | 3,724,844 | +1.0% |

| 2020 | 3,777,491 | +1.4% |

Yokohama's foreign population of 92,139 includes Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, and Vietnamese.[21]

Wards

Yokohama has 18 wards (ku):

| Wards of Yokohama | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place Name | Map of Yokohama | |||||

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Population | Land area in km2 | Pop. density

per km2 |

||

| 1 | Aoba-ku | 青葉区 | 302,643 | 35.14 | 8,610 |  A map of Yokohama's Wards |

| 2 | Asahi-ku | 旭区 | 249,045 | 32.77 | 7,600 | |

| 3 | Hodogaya-ku | 保土ヶ谷区 | 205,887 | 21.81 | 9,400 | |

| 4 | Isogo-ku | 磯子区 | 163,406 | 19.17 | 8,520 | |

| 5 | Izumi-ku | 泉区 | 155,674 | 23.51 | 6,620 | |

| 6 | Kanagawa-ku | 神奈川区 | 230,401 | 23.88 | 9,650 | |

| 7 | Kanazawa-ku | 金沢区 | 209,565 | 31.01 | 6,760 | |

| 8 | Kōhoku-ku | 港北区 | 332,488 | 31.40 | 10,588 | |

| 9 | Kōnan-ku | 港南区 | 221,536 | 19.87 | 11,500 | |

| 10 | Midori-ku | 緑区 | 176,038 | 25.42 | 6,900 | |

| 11 | Minami-ku | 南区 | 197,019 | 12.67 | 15,500 | |

| 12 | Naka-ku (administrative center) | 中区 | 146,563 | 20.86 | 7,030 | |

| 13 | Nishi-ku | 西区 | 93,210 | 7.04 | 13,210 | |

| 14 | Sakae-ku | 栄区 | 124,845 | 18.55 | 6,750 | |

| 15 | Seya-ku | 瀬谷区 | 126,839 | 17.11 | 7,390 | |

| 16 | Totsuka-ku | 戸塚区 | 274,783 | 35.70 | 7,697 | |

| 17 | Tsurumi-ku | 鶴見区 | 270,433 | 33.23 | 8,140 | |

| 18 | Tsuzuki-ku | 都筑区 | 211,455 | 27.93 | 7,535 | |

Government and politics

The Yokohama City Council consists of 86 members elected from a total of 18 Wards. The LDP has minority control with 36 seats. The incumbent mayor is Takeharu Yamanaka, who defeated Fumiko Hayashi in the 2021 Yokohama mayoral election.

List of mayors (from 1889)

|

|

Culture and sights

Yokohama's cultural and tourist sights include:

- Yokohama Chinatown

- Yokohama Three Towers

- Yamashita Park (at the harbor)

- Harbor View Park

- The Hikawa Maru, historic passenger and cargo ship

- Yokohama Marine Tower

- Yokohama Triennale

- Minato Mirai 21

- Landmark Tower, 296 m high, second tallest skyscraper in Japan

- Nippon Maru, museum ship

- Yokohama Stadium (the Yokohama DeNA BayStars Pro baseball teams's home field)

- Yokohama Foreign Cemetery

- Sankei-en Garden

- Kishine-Park

- Kanazawa Bunko, preserves the cultural heritage of the Hōjō clan

- Zō-no-Hana Terrace (象の鼻テラス)[22]

- Gumyōji, oldest temple in the city

Museums

There are 42 museums in the city area, including.[23]

- CupNoodles Museum (Momofuku Andō Instant Ramen Museum): Several-floors of interactive exhibits related to the invention of the Japanese instant noodle soup, including soup kitchens where you can try the culture-specific noodle soups.

- Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History: Located in the historic Yokohama Specie Bank building.

- Kanazawa Bunko: Traditional Japanese and Chinese art objects, many dating from the Kamakura period.

- Matsuri Museum: Dedicated to the shrine festivals (Japanese Matsuri) taking place in Yokohama.

- Silk Museum: Exhibits focusing on the production and processing of silk; including many clothes.

- Yokohama Archives of History: Located in the former British Consulate building with exhibits related to port development and the arrival of Matthew Perry.

- Yokohama Museum of Art: Founded in 1989, featuring modern works by well-known international and Japanese artists.

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Yokohama Three Towers and Ronald Reagan Boulevard.

Yokohama Three Towers and Ronald Reagan Boulevard. Harbor View Park towards the Yokohama Bay Bridge

Harbor View Park towards the Yokohama Bay Bridge

Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse and Douglas MacArthur Memorial Square

Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse and Douglas MacArthur Memorial Square Yokohama World Porters

Yokohama World Porters Mitsui Outlet Park Yokohama Bayside

Mitsui Outlet Park Yokohama Bayside Matthew C. Perry Zoo (formerly Yokohama Municipal Kanazawa Zoo)

Matthew C. Perry Zoo (formerly Yokohama Municipal Kanazawa Zoo)

Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery

Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery

Iseyama Kotai Shrine

Iseyama Kotai Shrine

Excursion destinations

In 2016, 46,017,157 tourists visited the city, 13.1% of whom were overnight guests.[23]

- Kodomo no kuni: Means "Children's country". A nice destination to spend an eventful day with the family. Lots of space for walking and playing. There is also a petting zoo.

- Nogeyama Zoo: One of the few zoos that do not charge admission. It has a large number of animals and a petting zoo where children can play with small animals.

- Zoorasia: Nice zoo with lots of play options for children. However, in this zoo admission costs.

- Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea Paradise: A large park with an aquarium. Otherwise rides, shops, restaurants, etc.

- Since 2020, after six years of development, a giant robot named Gundam, which is 18 meters high and weighs 25 tons, has been watching over the port area as a tourist attraction. The giant robot, in which there is a cockpit and whose hands are each two meters long, is based as a figure on a science fiction television series, can move and sink to its knees.[24] The giant robot was manufactured by the company "Gundam Factory Yokohama" under Managing Director Shin Sasaki.

- Kamonyama Park

In popular media

- Yukio Mishima's novel The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea is set mainly in Yokohama. Mishima describes the city's port and its houses, and the Western influences that shaped them.

- From Up on Poppy Hill is a 2011 Studio Ghibli animated drama film directed by Gorō Miyazaki set in the Yamate district of Yokohama. The film is based on the serialized Japanese comic book of the same name.

- The main setting of James Clavell's book Gai-Jin is in historical Yokohama.

- Vermillion City in the Kanto region from the Pokémon franchise is based on Yokohama. During the closing ceremony of the 2022 Pokémon World Championships in London, Yokohama was announced as the 2023 host city by using footage of Vermillion City from Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow. The 2023 World Championships were held at the Pacifico Yokohama between August 11th-13th 2023. In the video game division, the host country won the finals of all three age divisions.

- One of the Pretty Cure crossover movies takes place in Yokohama. In the fourth movie of the series, Pretty Cure All Stars New Stage: Friends of the Future, the Pretty Cure appear standing on top of the Cosmo Clock 21 in Minato Mirai.

- The main setting of the Japanese visual novel series Muv-Luv, first a school and then, in an alternate history, a military base is built in Yokohama with the objective of carrying out the Alternative IV Plan meant to save humanity.

- In Command & Conquer: Red Alert 3, Yokohama is under siege by the Soviet Union and Allied Nations to stop the Empire of The Rising Sun. The player must defend Yokohama and then lead a counterattack as the Empire.

- The manga Bungo Stray Dogs is set in Yokohama.

- The Japanese mixed-media project, Hamatora takes place in Yokohama.

- The final battle in Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack takes place in Yokohama.

- In My Hero Academia, it is the location of the Nomu Warehouse where they created artificial Humans (a.k.a. Nomus).

- Sumaru City in the Persona 2 duology is based on Yokohama.

- Miyabi City in The Caligula Effect is based on Yokohama, including depictions of landmarks such as an unfinished Landmark Tower and Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea Paradise (referred to in game as Sea Paraiso).

- The video game Yakuza: Like a Dragon is set in Isezaki Ijincho, a fictional district in Yokohama based on Isezakichō.

- Yokohama is also represented in the multimedia project by King Records, Hypnosis Mic: Division Rap Battle

- Yokohama is the main setting of Japanese manga and anime series Komi Can't Communicate. Multiple of the cities’ landmarks are featured on the manga, most notably in the more recently released chapters.

- Yokohama is the setting of the anime After the Rain as well as manga series with the same title by Jun Mayuzuki.

- In April 2022, The Yokohama Convention & Visitors Bureau announced the launch of a new interactive website to aid in the tourism and MICE elements of the city.[25]

Sports

Yokohama Stadium exterior

Yokohama Stadium exterior Yokohama Stadium crowd

Yokohama Stadium crowd Yokohama Arena exterior

Yokohama Arena exterior Nissan Stadium exterior

Nissan Stadium exterior Nissan Stadium crowd

Nissan Stadium crowd

- Baseball: Yokohama DeNA BayStars

- Soccer: Yokohama F. Marinos (J.League Division 1), Yokohama FC (J.League Division 1), YSCC Yokohama (J.League Division 3), NHK Yokohama FC Seagulls (Nadeshiko League Div.2)

- Velodrome: Kagetsu-en Velodrome

- Basketball: Yokohama B-Corsairs

- Rugby Union: Yokohama Eagles

- Tennis: Ai Sugiyama

- American football: Yokohama Harbors

Economy

The city has a strong economic base, especially in the shipping, biotechnology, and semiconductor industries. Nissan moved its headquarters to Yokohama from Chūō, Tokyo, in 2010.[26] Yokohama's GDP per capita (Nominal) was $30,625 ($1=¥120.13).[27][28]

As of 2016, the total production in Yokohama city reached ¥13.56 billion. It is located between Shizuoka and Hiroshima Prefectures compared to domestic prefectures.[29] It is located between Hungary, which ranks 26th, and New Zealand, which ranks 27th compared to OECD countries. Generally, the primary industry is 0.1%, the secondary industry is 21.7%, and the tertiary industry is 82.3%. The ratio of the primary industry is low, and the ratio of the secondary industry and the tertiary industry is high. Compared to other ordinance-designated cities, it is about 60% of the size of Osaka, which is almost the same as Nagoya. As shown in the attached table, there are not a few head office companies, but the major inferiority to Osaka is the traditional difference, the strong bed. In connection with this, the absence of large block-type companies (JR, NTT, electric power, gas, major commercial broadcasters, etc.) has had an impact.

The breakdown is ¥11.9 million yen (0.1%) for the primary industry, ¥2.75 billion (21.7%) for the secondary industry, and ¥10.44 billion yen (82.3%) for the tertiary industry. Compared to other government-designated cities, the amount of the primary industry, the ratio of the construction industry of the secondary industry, and the ratio of the real estate industry of the tertiary industry are large, and the finance, insurance, wholesale, and retail of the tertiary industry The ratio of industry and service industry is small, but the tertiary industry is almost the same as Nagoya.

Major companies headquartered

JVCKenwood headquarters in Kanagawa-ku

JVCKenwood headquarters in Kanagawa-ku Koei Tecmo headquarters in Kōhoku-ku

Koei Tecmo headquarters in Kōhoku-ku Keikyu Group headquarters in Nishi-ku

Keikyu Group headquarters in Nishi-ku Sotetsu headquarters in Nishi-ku

Sotetsu headquarters in Nishi-ku Isuzu headquarters in Nishi-ku

Isuzu headquarters in Nishi-ku

Transport

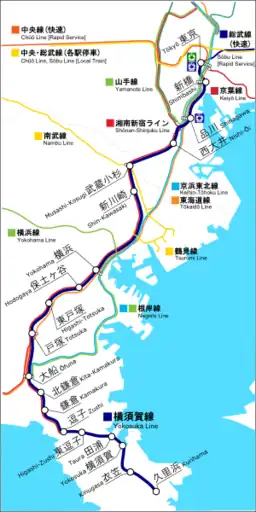

Yokohama is serviced by the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, a high-speed rail line with a stop at Shin-Yokohama Station. Yokohama Station is also a major station, with two million passengers daily. The Yokohama Municipal Subway, Minatomirai Line and Kanazawa Seaside Line provide metro services.

Air transport

Yokohama does not have an airport, but is served by Tokyo's two main airports Haneda Airport which is 17.4 km away and Narita International Airport which is 77 km away.

Maritime transport

Yokohama is the world's 31st largest seaport in terms of total cargo volume, at 121,326 freight tons as of 2011, and is ranked 37th in terms of TEUs (Twenty-foot equivalent units).[30]

In 2013, APM Terminals Yokohama facility was recognized as the most productive container terminal in the world averaging 163 crane moves per hour, per ship between the vessel's arrival and departure at the berth.[31]

Railway stations

- ■ East Japan Railway Company (JR East)

- ■ Tōkaidō Main Line

- ■ Yokosuka Line

- – Yokohama – Hodogaya – Higashi-Totsuka – Totsuka –

- ■ Keihin-Tōhoku Line

- – Tsurumi – Shin-Koyasu – Higashi-Kanagawa – Yokohama

- ■ Negishi Line

- Yokohama – Sakuragichō – Kannai – Ishikawachō – Yamate – Negishi – Isogo – Shin-Sugita – Yōkōdai – Kōnandai – Hongōdai –

- ■ Yokohama Line

- Higashi-Kanagawa – Ōguchi – Kikuna – Shin-Yokohama – Kozukue – Kamoi – Nakayama – Tōkaichiba – Nagatsuta –

- ■ Nambu Line

- – Yakō –

- ■ Tsurumi Line

- Main Line : Tsurumi – Kokudō – Tsurumi-Ono – Bentembashi – Asano – Anzen –

- Umi-Shibaura Branch : Asano – Shin-Shibaura – Umi-Shibaura

- ■ Central Japan Railway Company (JR Central)

- ■ Tōkaidō Shinkansen

- – Shin-Yokohama –

- ■ Keikyu

- ■ Keikyu Main Line

- – Tsurumi-Ichiba – Keikyū Tsurumi – Kagetsuen-mae – Namamugi – Keikyū Shin-Koyasu – Koyasu – Kanagawa-Shinmachi – Naka-Kido – Kanagawa – Yokohama – Tobe – Hinodechō – Koganechō – Minami-Ōta – Idogaya – Gumyōji – Kami-Ōoka – Byōbugaura – Sugita – Keikyū Tomioka – Nōkendai – Kanazawa-Bunko – Kanazawa-Hakkei –

- ■ Keikyu Zushi Line

- Kanazawa-Hakkei – Mutsuura –

- ■ Tokyu Railways

- ■ Tōyoko Line

- – Hiyoshi – Tsunashima – Ōkurayama – Kikuna – Myōrenji – Hakuraku – Higashi-Hakuraku – Tammachi – Yokohama

- ■ Meguro Line

- – Hiyoshi

- ■ Den-en-toshi Line

- ■ Kodomonokuni Line

- Nagatsuta – Onda – Kodomonokuni

- ■ Sagami Railway

- ■ Sagami Railway Main Line

- Yokohama – Hiranumabashi – Nishi-Yokohama – Tennōchō – Hoshikawa – Wadamachi – Kamihoshikawa – Nishiya – Tsurugamine – Futamata-gawa – Kibōgaoka – Mitsukyō – Seya –

- ■ Izumino Line

- Futamata-gawa – Minami-Makigahara – Ryokuentoshi – Yayoidai – Izumino – Izumi-chūō – Yumegaoka

- ■ Yokohama Minatomirai Railway

- ■ Minatomirai Line

- Yokohama – Shin-Takashima – Minato Mirai – Bashamichi – Nihon-ōdōri – Motomachi-Chūkagai

- ■ Yokohama City Transportation Bureau (Yokohama Municipal Subway)

- ■ Blue Line

- – Shimoiida – Tateba – Nakada – Odoriba – Totsuka – Maioka – Shimonagaya – Kaminagaya – Kōnan-Chūō – Kami-Ōoka – Gumyōji – Maita – Yoshinochō – Bandōbashi – Isezakichōjamachi – Kannai – Sakuragichō – Takashimachō – Yokohama – Mitsuzawa-shimochō – Mitsuzawa-kamichō – Katakurachō – Kishine-kōen – Shin-Yokohama – Kita Shin-Yokohama – Nippa – Nakamachidai – Center Minami – Center Kita – Nakagawa – Azamino

- ■ Green Line

- Nakayama – Kawawachō – Tsuzuki-Fureai-no-Oka – Center Minami – Center Kita – Kita-Yamata – Higashi-Yamata – Takata – Hiyoshi-Honchō – Hiyoshi

- ■ Yokohama New Transit

- ■ Kanazawa Seaside Line

- Shin-Sugita – Nambu-Shijō – Torihama – Namiki-Kita – Namiki-Chūō – Sachiura – Sangyō-Shinkō-Center – Fukuura – Shidai-Igakubu – Hakkeijima – Uminokōen-Shibaguchi – Uminokōen-Minamiguchi – Nojimakōen – Kanazawa-Hakkei

Education

Public elementary and middle schools are operated by the city of Yokohama. There are nine public high schools which are operated by the Yokohama City Board of Education,[32] and a number of public high schools which are operated by the Kanagawa Prefectural Board of Education. Yokohama National University is a leading university in Yokohama which is also one of the highest ranking national universities in Japan.

- 46,388 children attend the 260 kindergartens.

- Almost 386,000 students are taught in 351 primary schools.

- There are 16 universities including Yokohama National University. The number of students is around 83,000.

- 19 public libraries had 9.5 million loans in 2016.[23]

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Constanța, Constanța County, Romania (since October 1977)

Constanța, Constanța County, Romania (since October 1977) Lyon, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France (since April 1959)

Lyon, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France (since April 1959) Manila, Philippines (since July 1965)

Manila, Philippines (since July 1965) Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (since June 1965)

Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (since June 1965) Odesa, Odesa Oblast, Ukraine (since July 1965)

Odesa, Odesa Oblast, Ukraine (since July 1965) San Diego, CA, United States (since October 1957)

San Diego, CA, United States (since October 1957) Shanghai, China (since November 1973)

Shanghai, China (since November 1973).svg.png.webp) Vancouver, BC, Canada (since July 1965)

Vancouver, BC, Canada (since July 1965)

Partner cities

Abidjan, Ivory Coast

Abidjan, Ivory Coast Beijing, China (since May 2006)

Beijing, China (since May 2006).svg.png.webp) Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (since June 2008)

Brisbane, Queensland, Australia (since June 2008) Busan, South Korea (since June 2006)

Busan, South Korea (since June 2006) Frankfurt, Hesse, Germany (since September 2011)

Frankfurt, Hesse, Germany (since September 2011) Hanoi, Vietnam (since November 2007)

Hanoi, Vietnam (since November 2007) Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (since October 2007)

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (since October 2007) Incheon, South Korea (since December 2009)

Incheon, South Korea (since December 2009).svg.png.webp) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Seberang Perai, Penang, Malaysia (since August 2016)[34]

Seberang Perai, Penang, Malaysia (since August 2016)[34] Taipei, Taiwan (since May 2006)

Taipei, Taiwan (since May 2006) Tel Aviv, Israel (since July 2012)

Tel Aviv, Israel (since July 2012) Tianjin, China (since May 2008)

Tianjin, China (since May 2008)

Sister ports

Port of Barcelona, Spain (since November 1989)

Port of Barcelona, Spain (since November 1989) Port of Dalian (friendship port treaty, since September 1990)

Port of Dalian (friendship port treaty, since September 1990) Port of Hamburg, Germany (since October 1992)

Port of Hamburg, Germany (since October 1992).svg.png.webp) Port of Melbourne, Australia (since May 1986)

Port of Melbourne, Australia (since May 1986) Port of Oakland, United States (since May 1980)

Port of Oakland, United States (since May 1980).svg.png.webp) Port of Vancouver, Canada (since May 1981)

Port of Vancouver, Canada (since May 1981) Port of Shanghai (friendship port treaty, since October 1983)

Port of Shanghai (friendship port treaty, since October 1983)

Notable people

- Lily Abegg, journalist

- Jo Asakura, member of Japanese boy group &Team

- Toru Furuya, singer and seiyū

- Katsunori Iketani, racing driver

- Yuma Kagiyama, figure skater

- Masahiko Kondō, singer and racing driver

- Miki Koyama, racing driver

- Takehito Koyasu, singer and seiyū

- Ryuji Kumita, racing driver and CEO of B-Max Racing

- Keisuke Kunimoto, racing driver

- Yuji Kunimoto, racing driver

- Akinori Ogata, racing driver

- Takuro Shinohara, racing driver

- Minoru Suzuki, professional wrestler

- Miki Yamane, footballer

- Kuniaki Takahashi, drifting driver

- Yuta Watanabe, NBA player for the Toronto Raptors.

- Radwimps

- Crystal Kay, singer

- Naoya Inoue, boxer

References

Citations

- "YOKOHAMA | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com". En.oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- "Memories of old Honmoku". The Japan Times. May 19, 1999. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- "Yokohama City History, pg. 3" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Der Große Brockhaus. 16. edition. Vol. 6. F. A. Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 1955, p. 82

- "Official Yokohama city website it is fresh". City.yokohama.jp. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Arita, Erika, "Happy Birthday Yokohama! Archived August 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine", The Japan Times, May 24, 2009, p. 7.

- Driscoll, Mark W. (2020). The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1121-7.

- Fukue, Natsuko, "Chinese immigrants played vital role Archived August 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, May 28, 2009, p. 3.

- Matsutani, Minoru, "Yokohama – city on the cutting edge Archived August 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, May 29, 2009, p. 3.

- Galbraith, Michael (June 16, 2013). "Death threats sparked Japan's first cricket game". Japan Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "Interesting Tidbits of Yokohama". Yokohama Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- Hammer, Joshua. (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II, p. 143. Archived February 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Hammer, pp. 149 Archived February 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine-170.

- "Tsurumi River Multipurpose Retarding Basin". www.japanriver.or.jp. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Collection of 1923 Japan earthquake massacre testimonies released". www.hani.co.kr. September 3, 2013. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "FNN Remembering 3/11: Yokohama station and surrounding areas at time of earthquake occurrence". www.fnn-news.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Yokohama, Japan Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- "Yokohama Weather, When to Go and Yokohama Climate Information". world-guides.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- Japanese Imperial Commission (1878). Le Japon à l'exposition universelle de 1878. Géographie et histoire du Japon (in French).

- 横浜市区別外国人登録人口(平成30年3月末現在). Archived from the original on March 11, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- "Webseite des Kulturzentrums". Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- "Statistical Booklet Book of Yokohama 2018" (PDF). www.city.yokohama.lg.jp. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- Tagesthemen. Beitrag in der Nachrichtensendung der ARD, Moderation: Ingo Zamperoni, 30. November 2020, 35 Min. Eine Produktion von Das Erste

- "Virtual Yokohama: Interactive Website Launched". Business Wire. April 28, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- "Nissan To Create New Global and Domestic Headquarters in Yokohama City by 2010". Japancorp.net. Archived from the original on September 14, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "Yokohama GDP 2015". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- "Yokohama 2015 population" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- "「平成28年度 横浜市の市民経済計算」がまとまりました。" (PDF). 横浜市. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 4, 2021. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- "Ports & World Trade". www.aapa-ports.org. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- "Chinese Ports Lead the World in Berth Productivity, JOC Group Inc. Data Shows". Press Release. AXIO Data Group. JOC Inc. June 24, 2014. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- "Official Yokohama city website". City.yokohama.jp. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "Yokohama's Sister/Friendship Cities". city.yokohama.lg.jp. Yokohama. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- "MPSP sets sights on city status". The Star. August 1, 2016. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

Sources

- Hammer, Joshua (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6465-5 (cloth).

- Heilbrun, Jacob. "Aftershocks" Archived January 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, September 17, 2006.

External links

- Official Website (in Japanese)

- Yokohama Tourism Website (in English)

Geographic data related to Yokohama at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Yokohama at OpenStreetMap

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)