Acromegaly

Acromegaly is a disorder that results from excess growth hormone (GH) after the growth plates have closed. The initial symptom is typically enlargement of the hands and feet.[3] There may also be an enlargement of the forehead, jaw, and nose. Other symptoms may include joint pain, thicker skin, deepening of the voice, headaches, and problems with vision.[3] Complications of the disease may include type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and high blood pressure.[3]

| Acromegaly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lower jaw showing the classic spacing of teeth due to acromegaly. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Enlargement of the hands, feet, forehead, jaw, and nose, thicker skin, deepening of the voice[3] |

| Complications | Type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, high blood pressure[3] High cholesterol, Heart problems, particularly enlargement of the heart (cardiomyopathy), Osteoarthritis, Spinal cord compression or fractures, Increased risk of cancerous tumors, Precancerous growths (polyps) on the lining of your colon.[4] |

| Usual onset | Middle age[3] |

| Causes | Excess growth hormone[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, medical imaging[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pachydermoperiostosis[5] |

| Treatment | Surgery, medications, radiation therapy[3] |

| Medication | Somatostatin analogue, GH receptor antagonist[3] |

| Prognosis | Usually normal (with treatment), 10 year shorter life expectancy (no treatment)[6] |

| Frequency | 3 per 50,000 people[3] |

Acromegaly is usually caused by the pituitary gland producing excess growth hormone. In more than 95% of cases the excess production is due to a benign tumor, known as a pituitary adenoma. The condition is not inherited from a person's parents. Acromegaly is rarely due to a tumor in another part of the body. Diagnosis is by measuring growth hormone after a person has consumed a glucose solution, or by measuring insulin-like growth factor I in the blood. After diagnosis, medical imaging of the pituitary is carried out to determine if an adenoma is present. If excess growth hormone is produced during childhood, the result is the condition gigantism rather than acromegaly, and it is characterized by excessive height.[3]

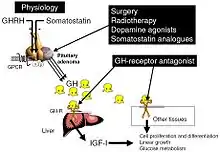

Treatment options include surgery to remove the tumor, medications, and radiation therapy. Surgery is usually the preferred treatment; the smaller the tumor, the more likely surgery will be curative. If surgery is contraindicated or not curative, somatostatin analogues or GH receptor antagonists may be used. Radiation therapy may be used if neither surgery nor medications are completely effective.[3] Without treatment, life expectancy is reduced by 10 years; with treatment, life expectancy is not reduced.[6]

Acromegaly affects about 3 per 50,000 people. It is most commonly diagnosed in middle age.[3] Males and females are affected with equal frequency.[7] It was first described in the medical literature by Nicolas Saucerotte in 1772.[8][9] The term is from the Greek ἄκρον (akron) meaning "extremity", and μέγα (mega) meaning "large".[3]

Signs and symptoms

Features that may result from a high level of GH or expanding tumor include:

- Headaches – often severe and prolonged

- Soft tissue swelling visibly resulting in enlargement of the hands, feet, nose, lips, and ears, and a general thickening of the skin

- Soft tissue swelling of internal organs, notably the heart with the attendant weakening of its muscularity, and the kidneys, also the vocal cords resulting in a characteristic thick, deep voice and slowing of speech

- Generalized expansion of the skull at the fontanelle

- Pronounced brow protrusion, often with ocular distension (frontal bossing)

- Pronounced lower jaw protrusion (prognathism) with attendant macroglossia (enlargement of the tongue) and teeth spacing

- Hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation and hyperhidrosis may occur in these people.[10]: 499

- Skin tags

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

Complications

- Problems with bones and joints, including osteoarthritis, nerve compression syndrome due to bony overgrowth, and carpal tunnel syndrome[11]

- Hypertension[11][12]

- Diabetes mellitus[13]

- Cardiomyopathy, potentially leading to heart failure[11]

- Colorectal cancer[14]

- Sleep Apnea[11]

- Thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer[15]

- Hypogonadism[11]

- Compression of the optic chiasm by the growth of pituitary adenoma leading to visual problems[16]

Causes

Pituitary adenoma

About 98% of cases of acromegaly are due to the overproduction of growth hormone by a benign tumor of the pituitary gland called an adenoma.[17] These tumors produce excessive growth hormone and compress surrounding brain tissues as they grow larger. In some cases, they may compress the optic nerves. Expansion of the tumor may cause headaches and visual disturbances. In addition, compression of the surrounding normal pituitary tissue can alter production of other hormones, leading to changes in menstruation and breast discharge in women and impotence in men because of reduced testosterone production.[18]

A marked variation in rates of GH production and the aggressiveness of the tumor occurs. Some adenomas grow slowly and symptoms of GH excess are often not noticed for many years. Other adenomas grow rapidly and invade surrounding brain areas or the sinuses, which are located near the pituitary. In general, younger people tend to have more aggressive tumors.[19]

Most pituitary tumors arise spontaneously and are not genetically inherited. Many pituitary tumors arise from a genetic alteration in a single pituitary cell that leads to increased cell division and tumor formation. This genetic change, or mutation, is not present at birth but is acquired during life. The mutation occurs in a gene that regulates the transmission of chemical signals within pituitary cells; it permanently switches on the signal that tells the cell to divide and secrete growth hormones. The events within the cell that cause disordered pituitary cell growth and GH oversecretion currently are the subject of intensive research.[19]

Pituitary adenomas and diffuse somatomammotroph hyperplasia may result from somatic mutations activating GNAS, which may be acquired or associated with McCune-Albright syndrome.[20][21]

Other tumors

In a few people, acromegaly is caused not by pituitary tumors, but by tumors of the pancreas, lungs, and adrenal glands. These tumors also lead to an excess of GH, either because they produce GH themselves or, more frequently, because they produce GHRH (growth hormone-releasing hormone), the hormone that stimulates the pituitary to make GH. In these people, the excess GHRH can be measured in the blood and establishes that the cause of the acromegaly is not due to a pituitary defect. When these nonpituitary tumors are surgically removed, GH levels fall and the symptoms of acromegaly improve.

In people with GHRH-producing, non-pituitary tumors, the pituitary still may be enlarged and may be mistaken for a tumor. Therefore, it is important that physicians carefully analyze all "pituitary tumors" removed from people with acromegaly so as to not overlook the possibility that a tumor elsewhere in the body is causing the disorder.

Diagnosis

If acromegaly is suspected, medical laboratory investigations followed by medical imaging if the lab tests are positive confirms or rules out the presence of this condition.

IGF1 provides the most sensitive lab test for the diagnosis of acromegaly, and a GH suppression test following an oral glucose load, which is a very specific lab test, will confirm the diagnosis following a positive screening test for IGF1. A single value of the GH is not useful in view of its pulsatility (levels in the blood vary greatly even in healthy individuals).

GH levels taken 2 hours after a 75- or 100-gram glucose tolerance test are helpful in the diagnosis: GH levels are suppressed below 1 μg/L in normal people, and levels higher than this cutoff are confirmatory of acromegaly.

Other pituitary hormones must be assessed to address the secretory effects of the tumor, as well as the mass effect of the tumor on the normal pituitary gland. They include thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), gonadotropic hormones (FSH, LH), adrenocorticotropic hormone, and prolactin.

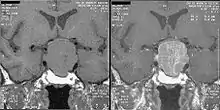

An MRI of the brain focusing on the sella turcica after gadolinium administration allows for clear delineation of the pituitary and the hypothalamus and the location of the tumor. A number of other overgrowth syndromes can result in similar problems.

Differential diagnosis

Pseudoacromegaly is a condition with the usual acromegaloid features, but without an increase in growth hormone and IGF-1. It is frequently associated with insulin resistance.[22] Cases have been reported due to minoxidil at an unusually high dose.[23] It can also be caused by a selective post receptor defect of insulin signalling, leading to the impairment of metabolic, but preservation of mitogenic, signalling.[24]

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to reduce GH production to normal levels thereby reversing or ameliorating the signs and symptoms of acromegaly, to relieve the pressure that the growing pituitary tumor exerts on the surrounding brain areas, and to preserve normal pituitary function. Currently, treatment options include surgical removal of the tumor, drug therapy, and radiation therapy of the pituitary.

Somatostatin analogues

The primary current medical treatment of acromegaly is to use somatostatin analogues – octreotide (Sandostatin) or lanreotide (Somatuline). These somatostatin analogues are synthetic forms of a brain hormone, somatostatin, which stops GH production. The long-acting forms of these drugs must be injected every 2 to 4 weeks for effective treatment. Most people with acromegaly respond to this medication. In many people with acromegaly, GH levels fall within one hour and headaches improve within minutes after the injection. Octreotide and lanreotide are effective for long-term treatment. Octreotide and lanreotide have also been used successfully to treat people with acromegaly caused by non-pituitary tumors.

Somatostatin analogues are also sometimes used to shrink large tumors before surgery.[25]

Because octreotide inhibits gastrointestinal and pancreatic function, long-term use causes digestive problems such as loose stools, nausea, and gas in one third of people. In addition, approximately 25 percent of people with acromegaly develop gallstones, which are usually asymptomatic.[26] In some cases, octreotide treatment can cause diabetes due to the fact that somatostatin and its analogues can inhibit the release of insulin. With an aggressive adenoma that is not able to be operated on, there may be a resistance to octreotide and in which case a second generation SSA, pasireotide, may be used for tumor control. However, insulin and glucose levels should be carefully monitored as pasireotide has been associated with hyperglycemia by reducing insulin secretion.[27]

Dopamine agonists

For those who are unresponsive to somatostatin analogues, or for whom they are otherwise contraindicated, it is possible to treat using one of the dopamine agonists, bromocriptine or cabergoline. As tablets rather than injections, they cost considerably less. These drugs can also be used as an adjunct to somatostatin analogue therapy. They are most effective in those whose pituitary tumours cosecrete prolactin. Side effects of these dopamine agonists include gastrointestinal upset, nausea, vomiting, light-headedness when standing, and nasal congestion. These side effects can be reduced or eliminated if medication is started at a very low dose at bedtime, taken with food, and gradually increased to the full therapeutic dose. Bromocriptine lowers GH and IGF-1 levels and reduces tumor size in fewer than half of people with acromegaly. Some people report improvement in their symptoms although their GH and IGF-1 levels still are elevated.

Growth hormone receptor antagonists

The latest development in the medical treatment of acromegaly is the use of growth hormone receptor antagonists. The only available member of this family is pegvisomant (Somavert). By blocking the action of the endogenous growth hormone molecules, this compound is able to control the disease activity of acromegaly in virtually everyone with acromegaly. Pegvisomant has to be administered subcutaneously by daily injections. Combinations of long-acting somatostatin analogues and weekly injections of pegvisomant seem to be equally effective as daily injections of pegvisomant.

Surgery

Surgical removal of the pituitary tumor is usually effective in lowering growth hormone levels. Two surgical procedures are available for use. The first is endonasal transsphenoidal surgery, which involves the surgeon reaching the pituitary through an incision in the nasal cavity wall. The wall is reached by passing through the nostrils with microsurgical instruments. The second method is transsphenoidal surgery during which an incision is made into the gum beneath the upper lip. Further incisions are made to cut through the septum to reach the nasal cavity, where the pituitary is located. Endonasal transsphenoidal surgery is a less invasive procedure with a shorter recovery time than the older method of transsphenoidal surgery, and the likelihood of removing the entire tumor is greater with reduced side effects. Consequently, endonasal transsphenoidal surgery is the more common surgical choice.

These procedures normally relieve the pressure on the surrounding brain regions and lead to a lowering of GH levels. Surgery is most successful in people with blood GH levels below 40 ng/ml before the operation and with pituitary tumors no larger than 10 mm in diameter. Success depends on the skill and experience of the surgeon. The success rate also depends on what level of GH is defined as a cure. The best measure of surgical success is the normalization of GH and IGF-1 levels. Ideally, GH should be less than 2 ng/ml after an oral glucose load. A review of GH levels in 1,360 people worldwide immediately after surgery revealed that 60% had random GH levels below 5 ng/ml. Complications of surgery may include cerebrospinal fluid leaks, meningitis, or damage to the surrounding normal pituitary tissue, requiring lifelong pituitary hormone replacement.

Even when surgery is successful and hormone levels return to normal, people must be carefully monitored for years for possible recurrence. More commonly, hormone levels may improve, but not return completely to normal. These people may then require additional treatment, usually with medications.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy has been used both as a primary treatment and combined with surgery or drugs. It is usually reserved for people who have tumor remaining after surgery. These people often also receive medication to lower GH levels. Radiation therapy is given in divided doses over four to six weeks. This treatment lowers GH levels by about 50 percent over 2 to 5 years. People monitored for more than 5 years show significant further improvement. Radiation therapy causes a gradual loss of production of other pituitary hormones with time. Loss of vision and brain injury, which have been reported, are very rare complications of radiation treatments.

Selection of treatment

The initial treatment chosen should be individualized depending on the person's characteristics, such as age and tumor size. If the tumor has not yet invaded surrounding brain tissues, removal of the pituitary adenoma by an experienced neurosurgeon is usually the first choice. After surgery, a person must be monitored long-term for increasing GH levels.

If surgery does not normalize hormone levels or a relapse occurs, a doctor will usually begin additional drug therapy. The current first choice is generally octreotide or lanreotide; however, bromocriptine and cabergoline are both cheaper and easier to administer. With all of these medications, long-term therapy is necessary, because their withdrawal can lead to rising GH levels and tumor re-expansion.

Radiation therapy is generally used for people whose tumors are not completely removed by surgery, for people who are not good candidates for surgery because of other health problems, and for people who do not respond adequately to surgery and medication.

Prognosis

Life expectancy of people with acromegaly is dependent on how early the disease is detected.[28] Life expectancy after the successful treatment of early disease is equal to that of the general population.[29] Acromegaly can often go on for years before diagnosis, resulting in poorer outcome, and it is suggested that the better the growth hormone is controlled, the better the outcome.[28] Upon successful surgical treatment, headaches and visual symptoms tend to resolve.[12] One exception is sleep apnea, which is present in around 70% of cases, but does not tend to resolve with successful treatment of growth hormone level.[11] While hypertension is a complication of 40% of cases, it typically responds well to regular regimens of blood pressure medication.[11] Diabetes that occurs with acromegaly is treated with the typical medications, but successful lowering of growth hormone levels often alleviates symptoms of diabetes.[11] Hypogonadism without gonad destruction is reversible with treatment.[11] Acromegaly is associated with a slightly elevated risk of cancer.[30]

Notable people

Famous people with acromegaly include:

- Daniel Cajanus (1704–1749), "The Finnish Goliath". His natural size portrait and femur are still extant. His height was estimated to have been 247 cm (8' 1").

- Mary Ann Bevan (1874–1933), an English woman, who after developing acromegaly, toured the sideshow circuit as "the ugliest woman in the world".

- André the Giant (born André Roussimoff, 1946–1993), French professional wrestler and actor[31][32]

- Salvatore Baccaro (1932–1984), Italian character actor. Active in B-movies, comedies, and horrors because of his peculiar features and spontaneous sympathy

- Paul Benedict (1938–2008), American actor. Best known for portraying Harry Bentley, The Jeffersons' English next door neighbour[33]

- Big Show (born Paul Wight; 1972), American professional wrestler and actor, had his pituitary tumor removed in 1991.[34]

- Eddie Carmel, born Oded Ha-Carmeili (1936–1972), Israeli-born entertainer with gigantism and acromegaly, popularly known as "The Jewish Giant"

- Ted Cassidy (1932–1979), American actor. Best known for portraying Lurch in the TV sitcom The Addams Family[35]

- Rondo Hatton (1894–1946), American journalist and actor. A Hollywood favorite in B-movie horror films of the 1930s and 1940s. Hatton's disfigurement, due to acromegaly, developed over time, beginning during his service in World War I.[36]

- Sultan Kösen, the world's tallest man

- Maximinus Thrax, Roman emperor (c. 173, reigned 235–238). Descriptions, as well as depictions, indicate acromegaly, though remains of his body are yet to be found.

- The Great Khali (born Dalip Singh Rana), Indian professional wrestler, is best known for his tenure with WWE. He had his pituitary tumor removed in 2012 at age 39.[37]

- Primo Carnera (1906–1967), nicknamed the Ambling Alp, was an Italian professional boxer and wrestler who reigned as the boxing World Heavyweight Champion from 29 June 1933 to 14 June 1934.

- Maurice Tillet (1903–1954), Russian-born French professional wrestler, is better known by his ring name, the French Angel.[38]

- Richard Kiel (1939–2014), actor, "Jaws" from two James Bond movies and Mr. Larson in Happy Gilmore[39]

- Pío Pico, the last Mexican Governor of California (1801–1894), manifested acromegaly without gigantism between at least 1847 and 1858. Some time after 1858, signs of the growth hormone-producing tumor disappeared along with all the secondary effects the tumor had caused in him. He looked normal in his 90s.[40] His remarkable recovery is likely an example of spontaneous selective pituitary tumor apoplexy.[41]

- Earl Nightingale (March 12, 1921 – March 25, 1989) was an American radio speaker and author, dealing mostly with the subjects of human character development, motivation, and meaningful existence. He was the voice during the early 1950s of Sky King, the hero of a radio adventure series, and was a WGN radio program host from 1950 to 1956. Nightingale was the author of The Strangest Secret, which economist Terry Savage has termed "…one of the great motivational books of all time." Nightingale’s daughter, Pamela, mentioned her father had acromegaly during a podcast about her father that aired in June 2022.

- Tony Robbins, motivational speaker[42]

- Carel Struycken, Dutch actor, 2.13 m (7.0 ft), is best known for playing Lurch in The Addams Family film trilogy, The Giant in Twin Peaks, Lwaxana Troi's silent Servant Mr. Homn in Star Trek: The Next Generation, and The Moonlight Man in Gerald's Game, based on the Stephen King book.[43]

- Peter Mayhew (1944–2019), British-American actor, was diagnosed with gigantism at age eight. Best known for portraying Chewbacca in the Star Wars film series.[44]

- Irwin Keyes, American actor. Best known for portraying Hugo Mojoloweski, George's occasional bodyguard on The Jeffersons[45]

- Morteza Mehrzad, Iranian Paralympian and medalist. Member of the Iranian sitting volleyball team. Top scorer in the 2016 gold medal match[46]

- Neil McCarthy, British actor. Known for roles in Zulu, Time Bandits, and many British television series[47]

- Nikolai Valuev, Russian politician and former professional boxer

- Antônio "Bigfoot" Silva, Brazilian kickboxer and mixed martial arts fighter.[48][49][50]

- (Leonel) Edmundo Rivero, Argentine tango singer, composer and impresario

It has been argued that Lorenzo de' Medici (1449–92) may have had acromegaly. Historical documents and portraits, as well as a later analysis of his skeleton, support the speculation.[51] Pianist and composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, noted for his hands that could comfortably stretch a 13th on the piano, was never diagnosed with acromegaly in his lifetime, but a medical article from 2006 suggests that he might have had it.[52]

The Bogdanoff twins had shown some signs of acromegaly and their continued denials that they had plastic surgery that greatly altered their facial appearance made some consider the disease. However, acromegaly was not proven before they died.

References

- "acromegaly". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- "acromegaly". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "Acromegaly". NIDDK. April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Acromegaly". mayoclinic.org.

- Guglielmi G, Van Kuijk C (2001). Fundamentals of Hand and Wrist Imaging. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 205. ISBN 9783540678540. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Ho K (2011). Growth Hormone Related Diseases and Therapy: A Molecular and Physiological Perspective for the Clinician. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 400. ISBN 9781607613176. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- Pack AI (2016). Sleep Apnea: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 291. ISBN 9781420020885. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- Pearce JM (2003). Fragments of Neurological History. World Scientific. p. 501. ISBN 9781783261109. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- Pearce JM (September 2006). "Nicolas Saucerotte: Acromegaly before Pierre Marie". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 15 (3): 269–75. doi:10.1080/09647040500471764. PMID 16887764. S2CID 22801883.

- James W, Berger T, Elston D (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Klibanski A, Bronstein MD, Chanson P, Lamberts SW, et al. (September 2013). "A consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly complications". Pituitary. 16 (3): 294–302. doi:10.1007/s11102-012-0420-x. PMC 3730092. PMID 22903574.

- Laws ER (March 2008). "Surgery for acromegaly: evolution of the techniques and outcomes". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 9 (1): 67–70. doi:10.1007/s11154-007-9064-y. PMID 18228147. S2CID 1365262.

- Fieffe S, Morange I, Petrossians P, Chanson P, Rohmer V, Cortet C, et al. (June 2011). "Diabetes in acromegaly, prevalence, risk factors, and evolution: data from the French Acromegaly Registry". European Journal of Endocrinology. 164 (6): 877–84. doi:10.1530/EJE-10-1050. PMID 21464140.

- Renehan AG, O'Connell J, O'Halloran D, Shanahan F, Potten CS, O'Dwyer ST, Shalet SM (2003). "Acromegaly and colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, biological mechanisms, and clinical implications". Hormone and Metabolic Research. 35 (11–12): 712–25. doi:10.1055/s-2004-814150. PMID 14710350.

- Wolinski K, Czarnywojtek A, Ruchala M (14 February 2014). "Risk of thyroid nodular disease and thyroid cancer in patients with acromegaly—meta-analysis and systematic review". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88787. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988787W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088787. PMC 3925168. PMID 24551163.

- Melmed S, Jackson I, Kleinberg D, Klibanski A (August 1998). "Current treatment guidelines for acromegaly". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 83 (8): 2646–52. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.8.4995. PMID 9709926.

- Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J (8 April 2015). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (19th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 2269–2271. ISBN 978-0071802154.

- Ganapathy, M. K.; Tadi, P. (2022). "Anatomy, Head and Neck, Pituitary Gland". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 31855373. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Ganapathy, M. K.; Tadi, P. (2022). "Anatomy, Head and Neck, Pituitary Gland". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 31855373. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Vortmeyer AO, Gläsker S, Mehta GU, Abu-Asab MS, Smith JH, Zhuang Z, et al. (July 2012). "Somatic GNAS mutation causes widespread and diffuse pituitary disease in acromegalic patients with McCune-Albright syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 97 (7): 2404–13. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1274. PMC 3791436. PMID 22564667.

- Salenave S, Boyce AM, Collins MT, Chanson P (June 2014). "Acromegaly and McCune-Albright syndrome". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 99 (6): 1955–69. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3826. PMC 4037730. PMID 24517150.

- Yaqub, Abid; Yaqub, Nadia (1 September 2008). "Insulin-mediated pseudoacromegaly: a case report and review of the literature". West Virginia Medical Journal. 104 (5): 12–16. PMID 18846753. Gale A201087184.

- Nguyen KH, Marks JG (June 2003). "Pseudoacromegaly induced by the long-term use of minoxidil". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 48 (6): 962–5. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.325. PMID 12789195.

- Sam AH, Tan T, Meeran K (2011). "Insulin-mediated 'pseudoacromegaly'". Hormones. 10 (2): 156–61. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1306. PMID 21724541.

- "Acromegaly and Gigantism". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Octreotide Side Effects". Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Yamamoto, Reina; Robert Shima, Kosuke; Igawa, Hirobumi; Kaikoi, Yuka; Sasagawa, Yasuo; Hayashi, Yasuhiko; Inoshita, Naoko; Fukuoka, Hidenori; Takahashi, Yutaka; Takamura, Toshinari (2018). "Impact of preoperative pasireotide therapy on invasive octreotide-resistant acromegaly". Endocrine Journal. 65 (10): 1061–1067. doi:10.1507/endocrj.ej17-0487. ISSN 0918-8959. PMID 30078825.

- Lugo G, Pena L, Cordido F (2012). "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acromegaly". International Journal of Endocrinology. 2012: 540398. doi:10.1155/2012/540398. PMC 3296170. PMID 22518126.

- Melmed S, Bronstein MD, Chanson P, Klibanski A, Casanueva FF, Wass JA, et al. (September 2018). "A Consensus Statement on acromegaly therapeutic outcomes". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 14 (9): 552–561. doi:10.1038/s41574-018-0058-5. PMC 7136157. PMID 30050156.

- Dal, Jakob; Leisner, Michelle Z; Hermansen, Kasper; Farkas, Dóra Körmendiné; Bengtsen, Mads; Kistorp, Caroline; Nielsen, Eigil H; Andersen, Marianne; Feldt-Rasmussen, Ulla; Dekkers, Olaf M; Sørensen, Henrik Toft; Jørgensen, Jens Otto Lunde (1 June 2018). "Cancer Incidence in Patients With Acromegaly: A Cohort Study and Meta-Analysis of the Literature". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 103 (6): 2182–2188. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-02457. PMID 29590449.

- "Andre the Giant: Bio". WWE.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "André the Giant official website". Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- Times Staff And Wire Reports (5 December 2008). "Paul Benedict dies at 70; actor from 'The Jeffersons' and 'Sesame Street'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016.

- Baines T. "Big Show at home in current role". Ottawa Sun. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015.

- "Hope for Acromegaly Patients". 30 January 2015. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Duryea B (27 June 1999). "Floridian: In love with a monster". St Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016.

- Harish A. "WWE Star Great Khali's Growth-Inducing Tumor Removed". ABC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Oliver G. "The French Angel was more man than monster". SLAM! Wrestling. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

- "Richard "Jaws" Kiel, Famed Bond Movie Villain, Raises Awareness Oflife-Threatening Hormone Disorder". Prnewswire.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- Login IS, Login J (July 2008). "Governor Pio Pico, the monster of California...no more: lessons in neuroendocrinology". Pituitary. 13 (1): 80–6. doi:10.1007/s11102-008-0127-1. PMC 2807602. PMID 18597174.

- Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR, Arafah BM (2008). "Pituitary tumor apoplexy: a review". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 23 (2): 75–90. doi:10.1177/0885066607312992. PMID 18372348. S2CID 34782106.

- Plaskin G (13 August 2013). "Playboy Interview: Tony Robbins". Playboy. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- McLellan, Dennis (27 December 1992). "Shedding Light on a Rare Disease : Woman Hopes O.C. Group Will Increase Awareness of Life-Threatening Effects of Excessive-Growth Illness". Los Angeles Times.

- "Remembering Peter". Peter Mayhew Foundation. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Dagan C (8 July 2015). "Irwin Keyes, Horror Movie Character Actor, Dies at 63". Variety. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- Davies GA (13 September 2016). "Paralympics' tallest ever competitor: 'My life has changed playing sitting volleyball'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Stampede P. "Neil McCarthy". The Avengers Forever. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "Ex-treinador de Pezão, André Benkei explica doença do lutador e afirma: 'Ele jamais colocaria a saúde em risco'".

- "TRT ban forces UFC headliner 'Bigfoot' Silva into surgery". 12 September 2014.

- "UFC title hopeful 'Bigfoot' Silva a real-life giant". USA Today.

- Lippi, Donatella; Phillipe Charlier; Paola Romagnani (May 2017). "Acromegaly in Lorenzo the Magnificent, father of the Renaissance". The Lancet. 389 (10084): 2104. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31339-9. PMID 28561004. S2CID 38097951.

- Ramachandran, Manoj; Jeffrey K Aronson (October 2006). "The diagnosis of art: Rachmaninov's hand span". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (10): 529–30. doi:10.1177/014107680609901015. PMC 1592053. PMID 17066567.

External links

- Acromegaly at Curlie

- 2011 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Guideline Archived 29 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service