Allantois

The allantois (plural allantoides or allantoises) is a hollow sac-like structure filled with clear fluid that forms part of a developing amniote's conceptus (which consists of all embryonic and extraembryonic tissues). It helps the embryo exchange gases and handle liquid waste.

| Allantois | |

|---|---|

Diagram illustrating a chicken egg in its 9th day with all extraembryonic membranes | |

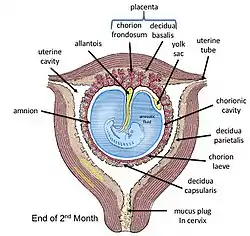

Allantois and other fetal membranes shown at end of second month of human pregnancy | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /əˈlæntɔɪs/ |

| Days | 16 |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Allantois |

| MeSH | D000482 |

| TE | E6.0.1.2.0.0.2 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The allantois, along with the amnion, chorion, and yolk sac (other extraembryonic membranes), identify humans and other mammals, birds, and other reptiles as amniotes. Fish and amphibians are anamniotes, and lack the allantois. In mammals the extraembryonic membranes are known as the fetal membranes.

Function

This sac-like structure, whose name is the New Latin equivalent of "sausage" (in reference to its shape when first formed)[1] is primarily involved in nutrition and excretion, and is webbed with blood vessels. The function of the allantois is to collect liquid waste from the embryo, as well as to exchange gases used by the embryo.

In mammals

In mammals excluding egg-laying monotremes, the allantois is one of the fetal membranes, and is part of and forms an axis for the development of the umbilical cord.

The human allantois is a caudal out-pouching of the yolk sac, which becomes surrounded by the mesodermal connecting stalk known as the body-stalk. The vasculature of the body-stalk develops into umbilical arteries that carry deoxygenated blood to the placenta.[2] It is externally continuous with the proctodeum and internally continuous with the cloaca. The embryonic allantois becomes the fetal urachus, which connects the fetal bladder (developed from cloaca) to the yolk sac. The urachus removes nitrogenous waste from the fetal bladder.[3] After birth the urachus becomes obliterated as the median umbilical ligament.

The mouse allantois consists of mesodermal tissue, which undergoes vasculogenesis to form the mature umbilical artery and vein.[4]

In marsupials

In most marsupials, the allantois is avascular, having no blood vessels, but still serves the purpose of storing nitrogenous (NH3) waste. Also, most marsupial allantoises do not fuse with the chorion. An exception is the allantois of the bandicoot, which has a vasculature, and fuses with the chorion.

In reptiles and birds

The structure first evolved in reptiles and birds as a reservoir for nitrogenous waste, and also as a means for oxygenation of the embryo. Oxygen is absorbed by the allantois through the egg shell.

Clinical significance

During the third week of embryonic development, the allantois protrudes into the area of the urogenital sinus. During fetal development, the allantois becomes the urachus, a duct between the bladder and the yolk sac. A patent allantois can result in a urachal cyst.

Additional images

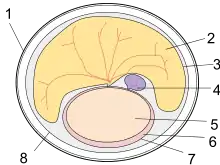

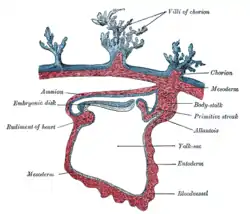

Section through the embryo.

Section through the embryo. Diagram showing later stage of allantoic development with commencing constriction of the yolk-sac.

Diagram showing later stage of allantoic development with commencing constriction of the yolk-sac. Opened uterus with cat fetus in midgestation: 1 umbilicus, 2 amniotic sac (chorion and amnion), 3 allantois, 4

Opened uterus with cat fetus in midgestation: 1 umbilicus, 2 amniotic sac (chorion and amnion), 3 allantois, 4

References

- "Allantois". dictionary.com.

- Moore, Keith; Persaud, T.V.N.; Torchia, Mark G. (2016). The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-323-31338-4.

- First AID for the USMLE Step 1 2008

- Downs, KM (1998). "The Murine Allantois". Curr Top Dev Biol. 39: 1–33. doi:10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60451-2. PMID 9475996.