Ascariasis

Ascariasis is a disease caused by the parasitic roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides.[1] Infections have no symptoms in more than 85% of cases, especially if the number of worms is small.[1] Symptoms increase with the number of worms present and may include shortness of breath and fever in the beginning of the disease.[1] These may be followed by symptoms of abdominal swelling, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.[1] Children are most commonly affected, and in this age group the infection may also cause poor weight gain, malnutrition, and learning problems.[1][2][5]

| Ascariasis | |

|---|---|

_(16238958958).jpg.webp) | |

| High number of ascaris worms – visible as black tangled mass – are filling the duodenum, the first portion of the bowel after the stomach, of this South African patient (X-ray image with barium as contrast medium). | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Abdominal swelling, abdominal pain, diarrhea, shortness of breath[1] |

| Causes | Ingestion of Ascaris eggs[2] |

| Prevention | Improved sanitation, handwashing[1] |

| Medication | Albendazole, mebendazole, levamisole, pyrantel pamoate[2] |

| Frequency | 762 million (2015)[3] |

| Deaths | 2,700 (2015)[4] |

Infection occurs by ingestion of food or drink contaminated with Ascaris eggs from feces.[2] The eggs hatch in the intestines, the larvae burrow through the gut wall, and migrate to the lungs via the blood.[2] There they break into the alveoli and pass up the trachea, where they are coughed up and may be swallowed.[2] The larvae then pass through the stomach for a second time into the intestine, where they become adult worms.[2] It is a type of soil-transmitted helminthiasis and part of a group of diseases called helminthiases.[6]

Prevention is by improved sanitation, which includes improving access to toilets and proper disposal of feces.[1][7] Handwashing with soap appears protective.[8] In areas where more than 20% of the population is affected, treating everyone at regular intervals is recommended.[1] Reoccurring infections are common.[2][9] There is no vaccine.[2] Treatments recommended by the World Health Organization are the medications albendazole, mebendazole, levamisole, or pyrantel pamoate.[2] Other effective agents include tribendimidine and nitazoxanide.[2]

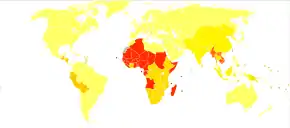

About 0.8 to 1.2 billion people globally have ascariasis, with the most heavily affected populations being in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia.[1][10][11] This makes ascariasis the most common form of soil-transmitted helminthiasis.[10] As of 2010 it caused about 2,700 deaths a year, down from 3,400 in 1990.[12] Another type of Ascaris infects pigs.[1] Ascariasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[6]

Signs and symptoms

In populations where worm infections are widespread, it is common to find that most people are infected by a small number of worms, while a small number of people are heavily infected. This is characteristic of many types of worm infections.[1][13] Those people who are infected with only a small number of worms usually have no symptoms.[14]

Migrating larvae

As larval stages travel through the body, they may cause visceral damage, peritonitis and inflammation, enlargement of the liver or spleen, and an inflammation of the lungs. Pulmonary manifestations take place during larval migration and may present as Loeffler's syndrome, a transient respiratory illness associated with blood eosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates with radiographic shadowing.[15]

Intestinal blockage

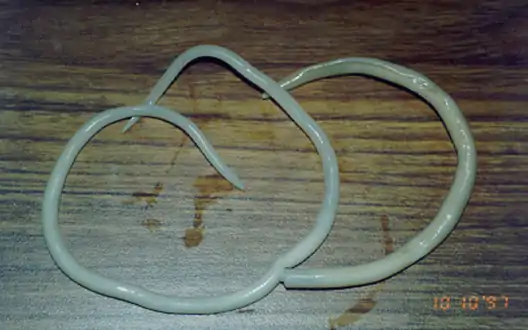

.jpg.webp)

The worms can occasionally cause intestinal blockage when large numbers get tangled into a bolus or they may migrate from the small intestine, which may require surgery. More than 796 A. lumbricoides worms weighing up to 550 g (19 oz) were recovered at autopsy from a two-year-old South African girl. The worms had caused torsion and gangrene of the ileum, which was interpreted as the cause of death.[17]

The worms lack teeth. However, they can rarely cause bowel perforations by inducing volvulus and closed-loop obstruction.

Bowel obstruction

Bowel obstruction may occur in up to 0.2 per 1000 per year.[1] A worm may block the ampulla of Vater, or go into the main pancreatic duct, resulting in acute pancreatitis with raised serum levels of amylase and lipase. Occasionally, a worm can travel through the biliary tree and even into the gallbladder, causing acute cholangitis or acute cholecystitis.[18]

Allergies

Ascariasis may result in allergies to shrimp and dustmites due to the shared antigen, tropomyosin; this has not been confirmed in the laboratory.[19][20]

Malnutrition

The worms in the intestine may cause malabsorption and anorexia, which contribute to malnutrition.[21] The malabsorption may be due to a loss of brush border enzymes, erosion and flattening of the villi, and inflammation of the lamina propria.[22]

Others

Ascaris have an aversion to some general anesthetics and may exit the body, sometimes through the mouth, when an infected individual is put under general anesthesia.[23]

Cause

The larva of Ascaris lumbricoides developing in the egg

The larva of Ascaris lumbricoides developing in the egg Ascaris lumbricoides adult worms (with measuring tape for scale)

Ascaris lumbricoides adult worms (with measuring tape for scale) Ascaris lumbricoides adult worms

Ascaris lumbricoides adult worms Ascaris egg, incubation process: The Ascaris egg incubation process consists of placing the egg in a controlled environment, at 26 °C (79 °F) during 28 days, in acidic conditions. This process allows for the evaluation of an egg to determine if it is viable or not.

Ascaris egg, incubation process: The Ascaris egg incubation process consists of placing the egg in a controlled environment, at 26 °C (79 °F) during 28 days, in acidic conditions. This process allows for the evaluation of an egg to determine if it is viable or not.

Transmission

The source of infection is from objects which have been contaminated with fecal matter containing eggs.[2] Ingestion of infective eggs from soil contaminated with human feces or contaminated vegetables and water is the primary route of infection. Infectious eggs may occur on other objects such as hands, money and furniture.[2] Transmission from human to human by direct contact is impossible.[24]

Transmission comes through municipal recycling of wastewater into crop fields. This is quite common in emerging industrial economies and poses serious risks for local crop sales and exports of contaminated vegetables. A 1986 outbreak of ascariasis in Italy was traced to irresponsible wastewater recycling used to grow Balkan vegetable exports.[25]

The number of ova (eggs) in sewage or in crops that were irrigated with raw or partially treated sewage, is a measure of the degree of ascariasis incidence. For example:

- In a study published in 1992, municipal wastewater in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, detected over 100 eggs per litre of wastewater[26] and in Czechoslovakia was as high as 240–1050 eggs per litre.[27]

- In one field study in Marrakech, Morocco, where raw sewage is used to fertilize crop fields, Ascaris eggs were detected at the rate of 0.18 eggs/kg in potatoes, 0.27 eggs/kg in turnip, 4.63 eggs/kg in mint, 0.7 eggs/kg in carrots, and 1.64 eggs/kg in radish.[28] A similar study in the same area showed that 73% of children working on these farms were infected with helminths, particularly Ascaris, probably as a result of exposure to the raw sewage.

Lifecycle

The first appearance of eggs in stools is 60–70 days. In larval ascariasis, symptoms occur 4–16 days after infection. The final symptoms are gastrointestinal discomfort, colic and vomiting, fever, and observation of live worms in stools. Some patients may have pulmonary symptoms or neurological disorders during migration of the larvae. There are generally few or no symptoms. A bolus of worms may obstruct the intestine; migrating larvae may cause pneumonitis and eosinophilia. Adult worms have a lifespan of 1–2 years which means that individuals may be infected all their lives as worms die and new worms are acquired.[13]

Eggs can survive potentially for 15 years and a single worm may produce 200,000 eggs a day.[2] They maintain their position by swimming against the intestinal flow.[29]

Mechanism

Ascaris takes most of its nutrients from the partially digested host food in the intestine. There is some evidence that it can secrete enzyme inhibitors, presumably to protect itself from digestion by the hosts' enzymes. Children are often more severely affected.[1]

Diagnosis

Most diagnoses are made by identifying the appearance of the worm or eggs in feces. Due to the large quantity of eggs laid, diagnosis can generally be made using only one or two fecal smears.[30] The diagnosis is usually incidental when the host passes a worm in the stool or vomit. The eggs can be seen in a smear of fresh feces examined on a glass slide under a microscope and there are various techniques to concentrate them first or increase their visibility, such as the ether sedimentation method or the Kato technique. The eggs have a characteristic shape: they are oval with a thick, mamillated shell (covered with rounded mounds or lumps), measuring 35–50 micrometer in diameter and 40–70 in length. During pulmonary disease, larvae may be found in fluids aspirated from the lungs. White blood cell counts may demonstrate peripheral eosinophilia; this is common in many parasitic infections and is not specific to ascariasis. On X-ray, 15–35 cm long filling defects, sometimes with whirled appearance (bolus of worms).

Prevention

Prevention is by improved access to sanitation which includes the use of properly functioning and clean toilets by all community members as one important aspect.[1] Handwashing with soap may be protective; however, there is no evidence it affects the severity of the disease.[8] Eliminating the use of untreated human faeces as fertilizer is also important.

In areas where more than 20% of the population is affected treating everyone is recommended.[1] This has a cost of about 2 to 3 cents per person per treatment.[1] This is known as mass drug administration and is often carried out among school-age children.[31] For this purpose, broad-spectrum benzimidazoles such as mebendazole and albendazole are the drugs of choice recommended by WHO.[32]

Treatment

Medications

Medications that are used to kill roundworms are called ascaricides. Those recommended by the World Health Organization for ascariasis are: albendazole, mebendazole, levamisole and pyrantel pamoate.[2] Single‐dose of albendazole, mebendazole, and ivermectin are effective against ascariasis. They are effective at removing parasites and eggs from the intestines.[33] Other effective agents include tribendimidine and nitazoxanide.[2] Pyrantel pamoate may induce intestinal obstruction in a heavy worm load. Albendazole is contraindicated during pregnancy and children under two years of age. Thiabendazole may cause migration of the worm into the esophagus, so it is usually combined with piperazine.

Piperazine is a flaccid paralyzing agent that blocks the response of Ascaris muscle to acetylcholine, which immobilizes the worm. It prevents migration when treatment is accomplished with weak drugs such as thiabendazole. If used by itself, it causes the worm to be passed out in the feces and may be used when worms have caused blockage of the intestine or the biliary duct.

Corticosteroids can treat some of the symptoms, such as inflammation.

Other medications

- Hexylresorcinol effective in single dose.[34] During the 1940s a crystoid form of this compound was the treatment of choice;[35] patients were instructed not to chew the crystoids in order to prevent burns to the mucous membranes. A saline cathartic would be administered several hours later.

- Santonin, more toxic than hexylresorcinol[34] and often only partly effective.[36]

- Oil of chenopodium, more toxic than hexylresorcinol[34]

Surgery

In some cases with severe infestation the worms may cause bowel obstruction, requiring emergency surgery.[37] The bowel obstruction may be due to all the worms or twisting of the bowel.[37] During the surgery the worms may be manually removed.[37]

Prognosis

It is rare for infections to be life-threatening.[1]

Epidemiology

Regions

Ascariasis is common in tropical regions as well as subtropical and regions that lack proper sanitation. It is rare to find traces of the infection in developed or urban regions.[38]

Infection estimates

Roughly 0.8–1.3 billion individuals are infected with this intestinal worm, primarily in Africa and Asia.[1][2][11] About 120 to 220 million of these cases are symptomatic.[1]

Deaths

As of 2010, ascariasis caused about 2,700 directly attributable deaths, down from 3,400 in 1990.[12] The indirectly attributable deaths due to the malnutrition link may be much higher.

Research

There are two animal models, the mouse and pig, used in studying Ascaris infection.[39][40]

Other animals

Ascariasis is more common in young animals than mature ones, with signs including unthriftiness, potbelly, rough hair coat, and slow growth.[41]

In pigs, the infection is caused by Ascaris suum. It is characterized by poor weight gain, leading to financial losses for the farmer.[1]

In horses and other equines, the equine roundworm is Parascaris equorum.

References

- Dold C, Holland CV (July 2011). "Ascaris and ascariasis". Microbes and Infection. 13 (7): 632–7. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2010.09.012. hdl:2262/53278. PMID 20934531.

- Hagel I, Giusti T (October 2010). "Ascaris lumbricoides: an overview of therapeutic targets". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets. 10 (5): 349–67. doi:10.2174/187152610793180876. PMID 20701574.

- Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- "Soil-transmitted helminth infections Fact sheet N°366". World Health Organization. June 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Ziegelbauer K, Speich B, Mäusezahl D, Bos R, Keiser J, Utzinger J (January 2012). "Effect of sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 9 (1): e1001162. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001162. PMC 3265535. PMID 22291577.

- Fung IC, Cairncross S (March 2009). "Ascariasis and handwashing". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 103 (3): 215–22. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.08.003. PMID 18789465.

- Jia TW, Melville S, Utzinger J, King CH, Zhou XN (2012). "Soil-transmitted helminth reinfection after drug treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (5): e1621. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001621. PMC 3348161. PMID 22590656.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J (2010). "The drugs we have and the drugs we need against major helminth infections". Advances in Parasitology. 73: 197–230. doi:10.1016/s0065-308x(10)73008-6. ISBN 978-0-12-381514-9. PMID 20627144.

- Fenwick A (March 2012). "The global burden of neglected tropical diseases". Public Health. 126 (3): 233–236. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.015. PMID 22325616.

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

- Anderson RS, May RM (1991). Infectious diseases of humans. Dynamics and control. Oxford: Oxford Scientific Publications.

- "Parasites - Ascariasis". C.D.C, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Torok E. Oxford Handbook Infect Dis and Microbiol, 2009

- Fincham, J., Dhansay, A. (2006). Worms in SA's children – MRC Policy Brief Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine. Nutritional Intervention Research Unit of the South African Medical Research Council, South Africa

- Baird JK, Mistrey M, Pimsler M, Connor DH (March 1986). "Fatal human ascariasis following secondary massive infection". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 35 (2): 314–8. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.314. PMID 3953945.

- "Acute Cholangitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Berman JJ (2012), Taxonomic Guide to Infectious Diseases: Understanding the Biologic Classes of Pathogenic Organisms, Academic Press, p. 151, ISBN 978-0-12-415895-5, archived from the original on 2013-05-30

- Reddy A, Fried B (2008). Rollinson D, Hay SI (eds.). "Atopic disorders and parasitic infections". Advances in Parasitology. 66: 149–91. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(08)00203-0. ISBN 978-0-08-087900-0. PMID 18486690.

- Hall A, Hewitt G, Tuffrey V, de Silva N (April 2008). "A review and meta-analysis of the impact of intestinal worms on child growth and nutrition" (PDF). Maternal & Child Nutrition. 4 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): 118–236. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00127.x. PMC 6860651. PMID 18289159.

- Stephenson LS (1987). The Impact of Helminth Infections on Human Nutrition. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Wu ML, Jones VA (January 2000). "Ascaris lumbricoides". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 124 (1): 174–5. doi:10.5858/2000-124-0174-AL. PMID 10629158.

- "AscarisInfection Fact Sheet". 2019-04-24. Archived from the original on 2010-05-31.

- Pawlowski ZS, Schultzberg K (1986). "Ascariasis and sewage in Europe". In Block JC (ed.). Epidemiological Studies of Risks Associated With the Agricultural Use of Sewage Sludge: Knowledge and Needs (EUR). Elsevier Science Pub Co. pp. 83–93. ISBN 978-1-85166-035-3.

- Bolbol AS (1992). "Risk of contamination of human and agricultural environment with parasites through reuse of treated municipal wastewater in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia". Journal of Hygiene, Epidemiology, Microbiology, and Immunology. 36 (4): 330–7. PMID 1300348.

- Horák P (1992). "Helminth eggs in the sludge from three sewage treatment plants in Czechoslovakia". Folia Parasitologica. 39 (2): 153–7. PMID 1644362.

- Habbari K, Tifnouti A, Bitton G, Mandil A (September 1999). "Helminthic infections associated with the use of raw wastewater for agricultural purposes in Beni Mellal, Morocco". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 5 (5): 912–21. doi:10.26719/1999.5.5.912. PMID 10983530.

- Crompton DW, Pawlowski ZS (1985). "Life history and development of Ascaris lumbricoides and the persistence of human ascariasis.". In Crompton DW, Nesheim MC, Pawlowski ZS (eds.). Ascariasis and its public health significance. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Grove DI (1990). A history of human helminthology. Wallingford: CAB International. pp. 1–848. ISBN 0-85198-689-7.

- Mascarini-Serra L (April 2011). "Prevention of Soil-transmitted Helminth Infection". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 3 (2): 175–82. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.81696. PMC 3125032. PMID 21731306.

- WHO (2006). Preventive Chemotherapy in Human Helminthiasis : Coordinated Use of Anthelminthic Drugs in Control Interventions : a Manual for Health Professionals and Programme Managers (PDF). WHO Press, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. pp. 1–61. ISBN 978-9241547109. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-02-28.

- Conterno LO, Turchi MD, Corrêa I, Monteiro de Barros Almeida RA, et al. (Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) (April 2020). "Anthelmintic drugs for treating ascariasis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4): CD010599. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010599.pub2. PMC 7156140. PMID 32289194.

- Holt, Jr Emmett L, McIntosh Rustin: Holt's Diseases of Infancy and Childhood: A Textbook for the Use of Students and Practitioners. Appleton and Co, New York,11th edition

- "Clinical Aspects and Treatment of the More Common Intestinal Parasites of Man (TB-33)". Veterans Administration Technical Bulletin 1946 & 1947. 10: 1–14. 1948.

- Ravina E (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 91. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Hefny AF, Saadeldin YA, Abu-Zidan FM (May 2009). "Management algorithm for intestinal obstruction due to ascariasis: a case report and review of the literature". Ulusal Travma Ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi = Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery. 15 (3): 301–5. PMID 19562557.

- "Parasites - Ascariasis". CDC, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- Howes HL (June 1971). "Anthelmintic studies with pyrantel. II. Prophylactic activity in a mouse-ascaris suum test model". The Journal of Parasitology. 57 (3): 487–93. doi:10.2307/3277899. JSTOR 3277899. PMID 5090955.

- Lichtensteiger CA, DiPietro JA, Paul AJ, Neumann EJ, Thompson L (April 1999). "Persistent activity of doramectin and ivermectin against Ascaris suum in experimentally infected pigs". Veterinary Parasitology. 82 (3): 235–41. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00018-7. PMID 10348103.

- "Parasites:Ascarids". eXtension. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- Mitchell PD, Yeh HY, Appleby J, Buckley R (September 2013). "The intestinal parasites of King Richard III". Lancet. 382 (9895): 888. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61757-2. hdl:2381/31491. PMID 24011545. S2CID 42898331.

- "Infected and Hunched: King Richard III Was Crawling with Roundworms". Live Science. 3 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

External links

- Image (warning, very graphic):Image 1

- CDC DPDx Parasitology Diagnostic Web Site