Necatoriasis

Necatoriasis is the condition of infection by Necator hookworms, such as Necator americanus.[1] This hookworm infection is a type of helminthiasis (infection) which is a type of neglected tropical disease.

| Necatoriasis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Signs and symptoms

When adult worms attach to the villi of the small intestine, they suck on the host's blood, which may cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, cramps, and weight loss that can lead to anorexia. Heavy infections can lead to the development of iron deficiency and hypochromic microcytic anemia. This form of anemia in children can give rise to physical and mental retardation. Infection caused by cutaneous larvae migrans, a skin disease in humans, is characterized by skin ruptures and severe itching.[2]

Cause

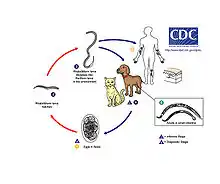

Necatoriasis is caused by N. americanus. N. americanus can be divided into two areas – larvae and adult stage. The third stage larvae are guided to human skin by following thermal gradients.[3] Typically, the larvae enter through the hands and feet following contact with contaminated soil. A papular, pruritic, itchy rash will develop around the site of entry into the human host.[4] This is also known as "ground itch". Generally, migration through the lungs is asymptomatic but a mild cough and pharyngeal irritation may occur during larval migration in the airways. Once larvae break through the alveoli and are swallowed, they enter the gastrointestinal tract and attach to the intestinal mucosa where they mature into adult worms. The hookworms attach to the mucosal lining using their cutting plates which allows them to penetrate blood vessels and feed on the host's blood supply. Each worm consumes 30 μl of blood per day. The major issue results from this intestinal blood loss which can lead to iron-deficiency anemia in moderate to heavy infections. Other common symptoms include epigastric pain and tenderness, nausea, exertional dyspnea, pain in lower extremities and in joints, sternal pain, headache, fatigue, and impotence.[5] Death is rare in humans.

Diagnosis

The standard method for diagnosing necatoriasis is through identification of N. americanus eggs in a fecal sample using a microscope. Eggs can be difficult to visualize in a lightly infected sample so a concentration method is generally used such as flotation or sedimentation.[6] However, the eggs of A. duodenale and N. americanus cannot be distinguished; thus, the larvae must be examined to identify these hookworms. Larvae cannot be found in stool specimens unless the specimen was left at ambient temperature for a day or more.

The most common technique used to diagnose a hookworm infection is to take a stool sample, fix it in 10% formalin, concentrate it using the formalin-ethyl acetate sedimentation technique, and then create a wet mount of the sediment for viewing under a microscope.

Prevention

Education, improved sanitation, and controlled disposal of human feces are critical for prevention. Nonetheless, wearing shoes in endemic areas helps reduce the prevalence of infection.

Treatment

An infection of N. americanus parasites can be treated by using benzimidazoles: albendazole or mebendazole. A blood transfusion may be necessary in severe cases of anemia. Light infections are usually left untreated in areas where reinfection is common. Iron supplements and a diet high in protein will speed the recovery process.[7] In a case study involving 56-60 men with Trichuris trichiura and/or N. americanus infections, both albendazole and mebendazole were 90% effective in curing T. trichiura. However, albendazole had a 95% cure rate for N. americanus, while mebendazole only had a 21% cure rate. This suggests albendazole is most effective for treating both T. trichiura and N. americanus.[8]

Cryotherapy by application of liquid nitrogen to the skin has been used to kill cutaneous larvae migrans, but the procedure has a low cure rate and a high incidence of pain and severe skin damage, so it now is passed over in favor of suitable pharmaceuticals. Topical application of some pharmaceuticals has merit, but requires repeated, persistent applications and is less effective than some systemic treatments.[9]

During the 1910s, common treatments for hookworm included thymol, 2-naphthol, chloroform, gasoline, and eucalyptus oil.[10] By the 1940s, the treatment of choice was tetrachloroethylene,[11] given as 3 to 4 cc in the fasting state, followed by 30 to 45 g of sodium sulfate. Tetrachloroethylene was reported to have a cure rate of 80 percent for Necator infections, but 25 percent in Ancylostoma infections, and often produced mild intoxication in the patient.

Epidemiology

Necator americanus was first discovered in Brazil and then was found in Texas. Later, it was found to be indigenous in Africa, China, southwest Pacific islands, India, and Southeast Asia. This parasite is a tropical parasite and is the most common species in humans. Roughly 95% of hookworms found in the southern region of the United States are N. americanus. This parasite is found in humans, but can also be found in pigs and dogs.

Transmission of N. americanus infection requires the deposition of egg-containing feces on shady, well-drained soil and is favored by warm, humid (tropical) conditions. Therefore, infections worldwide are usually reported in places where direct contact with contaminated soil occurs.

References

- Georgiev VS (May 2000). "Necatoriasis: treatment and developmental therapeutics". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 9 (5): 1065–78. doi:10.1517/13543784.9.5.1065. PMID 11060728. S2CID 8040066.

- "Necator americanus Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS)". Public Health Agency of Canada. 2001. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Haas, W., Haberl, B., Syafruddin, Idris, I., Kallert, D., Kersten, S., Stiegeler, P., & Syafruddin (2005). "Behavioural strategies used by the hookworms Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale to find, recognize and invade the human host". Parasitology Research. 95 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1007/s00436-004-1257-7. PMID 15614587. S2CID 24495300.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Hotez, P. J., Brooker, S., Bethony, J. M., Bottazzi, M. E., Loukas, A., & Xiao, S. (2004). "Hookworm infection" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (8): 799–807. doi:10.1056/NEJMra032492. PMID 15317893. S2CID 2281145.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Diemert, D. J., Bethony, J. M., & Hotez, P. J. (2008). "Hookworm vaccines". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (2): 282–288. doi:10.1086/524070. PMID 18171264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Gantz, Nelson Murray (2006). "Helminths". Manual of Clinical Problems in Infectious Disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 443.

- "hookworm disease". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Holzer, B. R.; and Frey, F. J. (February 1987). "Differential efficacy of mebendazole and albendazole against Necator americanus but not for Trichuris trichiura infestations". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 32 (6): 635–637. doi:10.1007/BF02456002. PMID 3653234. S2CID 19551476.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Caumes, Eric (2000). "Treatment of Cutaneous Larva Migrans". Clin Infect Dis. 30 (5): 811–814. doi:10.1086/313787. PMID 10816151.

- Milton, Joseph Rosenau (1913). Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. D. Appleton. p. 119.

- "Clinical Aspects and Treatment of the More Common Intestinal Parasites of Man (TB-33)". Veterans Administration Technical Bulletin 1946 & 1947. 10: 1–14. 1948.