Babesia microti

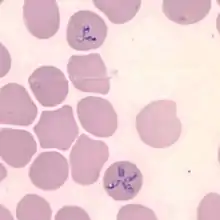

Babesia microti is a parasitic blood-borne piroplasm transmitted by deer ticks. B. microti is responsible for the disease babesiosis, a malaria-like disease which also causes fever and hemolysis.

| Babesia microti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Chromista |

| Superphylum: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Aconoidasida |

| Order: | Piroplasmida |

| Species: | B. microti |

| Binomial name | |

| Babesia microti (França, 1912) | |

Life cycle

The life cycle of B. microti includes human red blood cells and is an important transfusion-transmitted infectious organism. Between 2010 and 2014 it caused four out of fifteen (27%) fatalities associated with transfusion-transmitted microbial infections reported to the US FDA (the highest of any single organism).[1] In 2018, the FDA approved an antibody-based screening test for blood and organ donors.[2]

An important difference from malaria is that B. microti does not infect liver cells. Additionally, the piroplasm is spread by tick bites (Ixodes scapularis, the same tick that spreads Lyme disease), while the malaria protozoans are spread via mosquito. Finally, under the microscope, the merozoite form of the B. microti lifecycle in red blood cells forms a cross-shaped structure, often referred to as a "Maltese cross" or tetrad, in addition to intracellular "ring forms" which are also seen in the malaria parasite (Plasmodium spp.).[3]

Taxonomy

| Piroplasmida phylogeny (mtDNA)[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Until 2006 B. microti was thought to belong to the genus Babesia, as Babesia microti, until ribosomal RNA comparisons placed it in the sister genus Theileria.[5][6] As of 2012, the medical community still classified the parasite as Babesia microti[7] though its genome showed it does not belong to either Babesia or Theileria.[8]

Genomics

The genome of Babesia microti has been sequenced and published. [8]

The mitochondrial genome is circular.[8]

Vaccine

In May 2010, it was reported that a vaccine to protect cattle against East Coast fever had been approved and registered by the governments of Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania.[9]

A vaccine to protect humans has yet to be approved.[10]

References

- Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion: Annual Summary for Fiscal Year 2014 (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015.

- Approval Letter -Babesia microti AFIA/Babesia microti AFIA for Blood Donor Screening (PDF) (Report). Nicole Verdun (Review Office Signatory Authority); Mary A. Malarkey (Office of Compliance and Biologics Quality Signatory Authority). FDA. 6 March 2018. BLA/ STN#125589. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Goldberg, Stephen (2007). Clinical Microbiology made Ridiculously Simple (4th ed.). Medmaster. ISBN 978-0-940780-21-7.

- Schreeg, ME; Marr, HS; Tarigo, JL; Cohn, LA; Bird, DM; Scholl, EH; Levy, MG; Wiegmann, BM; Birkenheuer, AJ (2016). "Mitochondrial Genome Sequences and Structures Aid in the Resolution of Piroplasmida phylogeny". PLOS ONE. 11 (11): e0165702. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1165702S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165702. PMC 5104439. PMID 27832128.

- UILENBERG,G. GOFF,W.L. (2006). "Polyphasic Taxonomy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1081 (1): 492–7. Bibcode:2006NYASA1081..492U. doi:10.1196/annals.1373.073. PMID 17135557. S2CID 38312613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Uilenberg, G (May 2006). "Babesia--a historical overview". Veterinary Parasitology. 138 (1–2): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.035. PMID 16513280.

- Vannier, Edouard; Krause, Peter J. (21 June 2012). "Human Babesiosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (25): 2397–2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1202018. PMID 22716978.

- Cornillot, E.; Hadj-Kaddour, K.; Dassouli, A.; Noel, B.; Ranwez, V.; Vacherie, B.; Augagneur, Y.; Bres, V.; Duclos, A.; Randazzo, S.; Carcy, B.; Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Delbecq, S.; Moubri-Menage, K.; Shams-Eldin, H.; Usmani-Brown, S.; Bringaud, F.; Wincker, P.; Vivares, C. P.; Schwarz, R. T.; Schetters, T. P.; Krause, P. J.; Gorenflot, A.; Berry, V.; Barbe, V.; Ben Mamoun, C. (2012). "Sequencing of the smallest Apicomplexan genome from the human pathogen Babesia microti". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (18): 9102–14. doi:10.1093/nar/gks700. PMC 3467087. PMID 22833609.

- Florin-Christensen, Monica; Suarez, Carlos E.; Rodriguez, Anabel E.; Flores, Daniela A.; Schnittger, Leonhard (October 2014). "Vaccines against bovine babesiosis: where we are now and possible roads ahead". Parasitology. 141 (12): 1563–1592. doi:10.1017/S0031182014000961. PMID 25068315. S2CID 34025694.

- Puri, Ankit; Bajpai, Surabhi; Meredith, Scott; Aravind, L.; Krause, Peter J.; Kumar, Sanjai (2021). "Babesia microti: Pathogen Genomics, Genetic Variability, Immunodominant Antigens, and Pathogenesis". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 697669. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.697669. PMC 8446681. PMID 34539601. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

External links

- Babesia microti Minnesota Department of Health