Congenital generalized lipodystrophy

Congenital generalized lipodystrophy (also known as Berardinelli–Seip lipodystrophy) is an extremely rare autosomal recessive condition, characterized by an extreme scarcity of fat in the subcutaneous tissues.[2] It is a type of lipodystophy disorder where the magnitude of fat loss determines the severity of metabolic complications.[3] Only 250 cases of the condition have been reported, and it is estimated that it occurs in 1 in 10 million people worldwide.[4]

| Congenital generalized lipodystrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Berardinelli–Seip syndrome |

| |

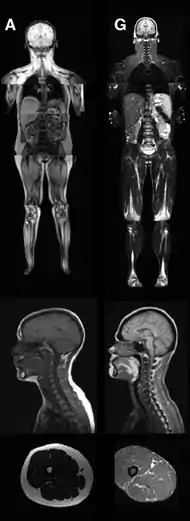

| An MRI image illustrating the lack of subcutaneous fat of a patient with the disease (G) compared to a control patient (A) | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Mild specific body features, absence of subcutaneous fat, muscle hypertrophy, insulin resistance, gigantism/acromegaly, large appetite[1] |

| Complications | Heart disease, kidney failure, cirrhosis, infertility(women), |

| Usual onset | After birth |

| Types | CGL type 1, CGL type 2, CGL type 3, CGL type 4 |

Presentation

Congenital generalized lipodystrophy (CGL) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder which manifests with insulin resistance, absence of subcutaneous fat and muscular hypertrophy.[5] Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in four genes are associated with the four subtypes of CGL.[3] The condition appears in early childhood with accelerated linear growth, quick aging of bones, and a large appetite. As the child grows up, acanthosis nigricans (hyperpigmentation and thickening of skin) will begin to present itself throughout the body – mainly in the neck, trunk, and groin.[4] The disorder also has characteristic features like hepatomegaly or an enlarged liver which arises from fatty liver and may lead to cirrhosis, muscle hypertrophy, lack of adipose tissue, splenomegaly, hirsutism (excessive hairiness) and hypertriglyceridemia.[6] Fatty liver and muscle hypertrophy arise from the fact that lipids are instead stored in these areas; whereas in a healthy individual, lipids are distributed more uniformly throughout the body subcutaneously. The absence of adipose tissue where they normally occur causes the body to store fat in the remaining areas.[7] Common cardiovascular problems related to this syndrome are cardiac hypertrophy and arterial hypertension (high blood pressure).[8] This disorder can also cause metabolic syndrome. Most with the disorder also have a prominent umbilicus or umbilical hernia. Commonly, patients will also have acromegaly with enlargement of the hands, feet, and jaw. After puberty, additional symptoms can develop. In women, clitoromegaly and polycystic ovary syndrome can develop. This impairs fertility for women, and only a few documented cases of successful pregnancies in women with CGL exist. However, the fertility of men with the disorder is unaffected.[4]

Type 1 vs Type 2 Differences

There are differences in how Type 1 vs Type 2 patients are affected by the disease. In type 1 patients, they still have mechanical adipose tissue, but type 2 patients do not have any adipose tissue, including mechanical.[9] In type 2 patients, there is a greater likelihood of psychomotor retardation and intellectual impairment.[10]

Genetics

| OMIM | Type | Gene Locus |

|---|---|---|

| 608594 | CGL1 | AGPAT2 at 9q34.3 |

| 269700 | CGL2 | BSCL2 at 11q13 |

| 612526 | CGL3 | CAV1 at 7q31.1 |

| 613327 | CGL4 | PTRF at 17q21 |

Mechanism

Type 1

In individuals with Type 1 CGL, the disorder is caused by a mutation at the AGPAT2 gene encoding 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 2 and located at 9q34.3. This enzyme catalyzes the acylation of lysophosphatidic acid to form phosphatidic acid, which is important in the biosynthesis of fats. This enzyme is highly expressed in adipose tissue, so it can be concluded that when the enzyme is defective in CGL, lipids cannot be stored in the adipose tissue.[11]

Type 2

In those who have Type 2 CGL, a mutation in the BSCL2 gene encoding the Seipin protein and located at 11q13. This gene encodes a protein, Seipin, whose function is unknown. Expression of mRNA for the seipin protein is high in the brain, yet low in adipose tissues. Additionally, patients which have mutations in this protein have a higher incidence of mental retardation and lack mechanically active adipose tissue, which is present in those with AGPAT2 mutations.[4]

Type 3

Type 3 CGL involves a mutation in the CAV1 gene. This gene codes for the Caveolin protein, which is a scaffolding membrane protein. This protein plays a role in lipid regulation. High levels of Cav1 are normally expressed in adipocytes. Thus, when the CAV1 gene mutates the adipocytes do not have Cav1 and are unable to properly regulate lipid levels.[12]

Type 4

A mutation in the PTRF gene causes Type 4 CGL. This gene codes for a protein called polymerase I and transcript release factor. One of the roles the PTRF product has it to stabilize and aid in formation of caveolae. Thus, the mechanism is similar to Type 3, in that the caveolae are unable to properly form and carry out their role in lipid regulation in both. Types 3 and 4 are two different mutations but they share a common defective pathway.[13]

Diagnosis

Medical diagnosis of CGL can be made after observing the physical symptoms of the disease: lipoatrophy (loss of fat tissues) affecting the trunk, limbs, and face; hepatomegaly; acromegaly; insulin resistance; and high serum levels of triglycerides. Genetic testing can also confirm the disease, as mutations in the AGPAT2 gene is indicative of CGL1, a mutation in the BSCL2 gene is indicative of CGL2, and mutations in the CAV1 and PTRF genes are indicative of CGL3 and CGL4 respectively.[10] Physical diagnosis of CGL is easier, as CGL patients are recognizable from birth, due to their extreme muscular appearance, which is caused by the absence of subcutaneous fat.[9]

CGL3 patients have serum creatine kinase concentrations much higher than normal (2.5 to 10 times the normal limit). This can be used to diagnose type 3 patients and differentiate them from CGL 1 and 2 without mapping their genes. Additionally, CGL3 patients have low muscle tone when compared with other CGL patients.[14]

Treatment

Metformin is the main drug used for treatment, as it is normally used for patients with hyperglycemia.[15] Metformin reduces appetite and improves symptoms of hepatic steatosis and polycystic ovary syndrome.[4] Leptin can also be used to reverse insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis, to cause reduced food intake, and decrease blood glucose levels.[16]

Diet

CGL patients have to maintain a strict diet for life, as their excess appetite will cause them to overeat. Carbohydrate intake should be restricted in these patients. To avoid chylomicronemia, CGL patients with hypertriglyceridemia need to have a diet very low in fat. CGL patients also need to avoid total proteins, trans fats, and eat high amounts of soluble fiber to avoid getting high levels of cholesterol in the blood.[17]

History

Congenital Generalized Lipodystrophy, also known as Berardinelli–Seip lipodystrophy was first described in 1954 by Berardinelli[18] and later by Seip in 1959.[19] The gene for type 1 CGL was identified as AGPAT2 at chromosome 9q34,[20] and later the gene for type 2 CGL was identified as BSCL2 at chromosome 11q13.[21] More recently, type 3 CGL was identified as a separate type of CGL, which was identified as a mutation in the CAV1 gene. Then, a separate type 4 CGL was identified as a mutation in the PTRF gene.[22]

See also

References

- "Congenital Generalized Lipodystrophy".

- James, William D; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 495. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- "Lipodystrophy Disorders – Inherited Lipodystrophies – NORD Physician Guides – Rare Disease Resources for Medical Professionals". NORD Physician Guides – Rare Disease Resources for Medical Professionals. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- Garg, A (Mar 2004). "Acquired and inherited lipodystrophies". The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (12): 1220–1234. doi:10.1056/NEJMra025261. PMID 15028826.

- Friguls, B; Coroleu, W; del Alcazar, R; Hilbert, P; et al. (2009). "Severe cardiac phenotype of Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy in an infant with homozygous E189X BSCL2 mutation". Eur J Med Genet. 52 (1): 14–6. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.10.006. PMID 19041432.

- Gürakan, F; Koçak, N; Yüce, A (1995). "Congenital generalized lipodystrophy: Berardinelli syndrome. Report of two siblings". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 37 (3): 241–6. PMID 7502362.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "congenital generalized lipodystrophy". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- Viégas, RF; Diniz, RV; Viégas, TM; Lira, EB; et al. (September 2000). "Cardiac involvement in total generalized lipodystrophy (Berardinelli- Seip syndrome)" (PDF). Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 75 (3): 243–8. doi:10.1590/s0066-782x2000000900006. PMID 11018810.

- Khandpur, S (2011). "Congenital generalized lipodystrophy of Berardinelli-Seip type: A rare case". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 77 (3): 402. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.79740. PMID 21508592.

- Van Maldergem, Lionel (1993). "Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy". University of Washington, Seattle. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- Agarwal, AK; Arioglu, E; de Almeida, S; Akkoc, N; et al. (May 2002). "AGPAT2 is mutated in congenital generalized lipodystrophy linked to chromosome 9q34". Nature Genetics. 31 (1): 21–23. doi:10.1038/ng880. PMID 11967537.

- Parton, RG; Simons, K (2007). "The multiple faces of caveolae". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (3): 185–94. doi:10.1038/nrm2122. PMID 17318224. S2CID 10830810.

- "PTRF". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- Kim, CA; Delépine, M; Boutet, E; et al. (April 2008). "Association of a Homozygous Nonsense Caveolin-1 Mutation with Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 93 (4): 1129–1134. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-1328. PMID 18211975.

- Victoria, I; Saad, M; Purisch, S; Pardini, V (May 1997). "Metformin improves metabolic control in subjects with congenital generalized lipoatrophic diabetes". Diabetes. 46: 618.

- Petersen, KF; Oral, EA; Dufour, S; Befroy, Douglas; et al. (May 2002). "Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 109 (10): 1345–1350. doi:10.1172/JCI15001. PMC 150981. PMID 12021250.

- Gomes, K; Pardini, VC; Fernandes, AP (April 2009). "Clinical and molecular aspects of Berardinelli–Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy (BSCL)". Clinica Chimica Acta. 402 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2008.12.032. PMID 19167372.

- Berardinelli, W (February 1954). "An undiagnosed endocrinometabolic syndrome: Report of 2 cases". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 14 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1210/jcem-14-2-193. PMID 13130666. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- Seip, M (November 1959). "Lipodystrophy and gigantism with associated endocrine manifestations. A new diencephalic syndrome?". Acta Paediatrica. 48: 555–74. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1959.tb17558.x. PMID 14444642. S2CID 27039847.

- Garg, A; Ross, W; Barnes, R; et al. (1999). "A gene for congenital generalized lipodystrophy maps to chromosome 9q34". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 84 (9): 3390–3394. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.9.6103. PMID 10487716.

- Magre, J; Delepine, M; Khallouf, E; et al. (2001). "Identification of the gene altered in Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy on chromosome 11q13". Nature Genetics. 28 (4): 365–370. doi:10.1038/ng585. PMID 11479539. S2CID 7718256.

- Shastry, S; Delgado, MR; Dirik, E; Turkmen, M; et al. (2010). "Congenital generalized lipodystrophy, type 4 (CGL4) associated with myopathy due to novel PTRF mutations". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 152A (9): 2245–53. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33578. PMC 2930069. PMID 20684003.