Cowden syndrome

Cowden syndrome (also known as Cowden's disease and multiple hamartoma syndrome) is an autosomal dominant inherited condition characterized by benign overgrowths called hamartomas as well as an increased lifetime risk of breast, thyroid, uterine, and other cancers.[1] It is often underdiagnosed due to variability in disease presentation, but 99% of patients report mucocutaneous symptoms by age 20–29.[2] Despite some considering it a primarily dermatologic condition, Cowden's syndrome is a multi-system disorder that also includes neurodevelopmental disorders such as macrocephaly.[3]

| Cowden syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cowden's disease, multiple hamartoma syndrome |

| |

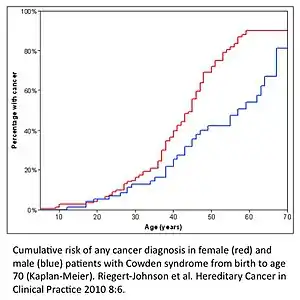

| Cumulative risk for the development of cancer in males and females with Cowden syndrome from birth to age 70. | |

| Specialty | Oncology, Dermatology, Gastroenterology, Neurology |

| Frequency | 1 in 200,000 individuals |

The incidence of Cowden's disease is about 1 in 200,000, making it quite rare.[4] Furthermore, early and continuous screening is essential in the management of this disorder to prevent malignancies.[4] It is associated with mutations in PTEN on 10q23.3, a tumor suppressor gene otherwise known as phosphatase and tensin homolog, that results in dysregulation of the mTOR pathway leading to errors in cell proliferation, cell cycling, and apoptosis.[5] The most common malignancies associated with the syndrome are adenocarcinoma of the breast (20%), followed by adenocarcinoma of the thyroid (7%), squamous cell carcinomas of the skin (4%), and the remaining from the colon, uterus, or others (1%).[6]

Signs and symptoms

As Cowden's disease is a multi-system disorder, the physical manifestations are broken down by organ system:

Skin

Adolescent patients affected with Cowden syndrome develop characteristic lesions called trichilemmomas, which typically develop on the face, and verrucous papules around the mouth and on the ears.[7] Oral papillomas are also common.[7] Furthermore, shiny palmar keratoses with central dells are also present.[7] At birth or in childhood, classic features of Cowden's include pigmented genital lesions, lipomas, epidermal nevi, and cafe-au-lait spots.[7] Squamous cell carcinomas of the skin may also occur.[6]

Thyroid

Two thirds of patients have thyroid disorders, and these typically include benign follicular adenomas or multinodular goiter of the thyroid.[8] Additionally, Cowden's patients are more susceptible to developing thyroid cancer than the general population.[9] It is estimated that less than 10 percent of individuals with Cowden syndrome may develop follicular thyroid cancer.[8] Cases of papillary thyroid cancer have been reported as well.[3]

Female and Male Genitourinary

Females have an elevated risk of developing endometrial cancers, which is highest for those under the age of 50.[3] Currently, it is not clear whether uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) or congenital genitourinary abnormalities occur at an increased rate in Cowden syndrome patients as compared to the general population.[3] The occurrence of multiple testicular lipomas, or testicular lipomatosis, is a characteristic finding in male patients with Cowden syndrome.[3]

Gastrointestinal

Polyps are extremely common as they are found in about 95% of Cowden syndrome patients undergoing a colonoscopy.[3] They are numerous ranging from a few to hundreds, usually of the hamartomatous subtype, and distributed across the colon as well as other areas within the gastrointestinal tract.[3][10] Other types of polyps that may be encountered less frequently include ganglioneuromatous, adenomatous, and lymphoid polyps.[10] Diffuse glycogenic acanthosis of the esophagus is another gastrointestinal manifestation associated with Cowden syndrome.[3]

Breast

Females are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer, which is the most common malignancy observed in Cowden's patients.[3] Although some cases have been reported, there is not enough evidence to indicate an association between Cowden syndrome and the development of male breast cancer.[3] Up to 75% demonstrate benign breast conditions such as intraductal papillomatosis, fibroadenomas, and fibrocystic changes.[3] However, there is currently not enough evidence to determine if benign breast disease occurs more frequently in Cowden's patients as compared to individuals without a hereditary cancer syndrome.[3]

Central Nervous System

Macrocephaly is observed in 84% of patients with Cowden syndrome.[11] It typically occurs due to an abnormally enlarged brain, or megalencephaly.[12] Patients may also exhibit dolichocephaly.[12] Varying degrees of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability have been reported as well.[11] Lhermitte-Duclos disease is a benign cerebellar tumor that typically does not manifest until adulthood in patients with Cowden syndrome.[13]

Genetics

Cowden syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.[14] Germline mutations in PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), a tumor suppressor gene, are found in up to 80% of Cowden's patients.[10] Several other hereditary cancer syndromes, such as Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, have been associated with mutations in the PTEN gene as well.[15] PTEN negatively regulates the cytoplasmic receptor tyrosine kinase pathway, which is responsible for cell growth and survival, and also functions to repair errors in DNA.[14][10] Thus, in the absence of this protein, cancerous cells are more likely to develop, survive, and proliferate.[10]

Recently, it was discovered that germline heterozygous mutations in SEC23B, a component of coat protein complex II vesicles secreted from the endoplasmic reticulum, are associated with Cowden syndrome.[16] A possible interplay between PTEN and SEC23B has recently been suggested, given emerging evidence of each having a role in ribosome biogenesis, but this has not been conclusively determined.[17]

Diagnosis

The revised clinical criteria for the diagnosis of Cowden's syndrome for an individual is dependent on either one of the following: 1) 3 major criteria are met or more that must include macrocephaly, Lhermitte-Duclos, or GI hamartomas 2) two major and three minor criteria.[3] The major and minor criteria are listed below:

| Major criteria |

| Breast cancer |

| Endometrial cancer (epithelial) |

| Thyroid cancer (follicular) |

| Gastrointestinal hamartomas (including ganglioneuromas, but excluding hyperplastic polyps; ≥3) |

| Lhermitte-Duclos disease (adult) |

| Macrocephaly (≥97 percentile: 58 cm for females, 60 cm for males) |

| Macular pigmentation of the glans penis |

| Multiple mucocutaneous lesions (any of the following): |

| Multiple trichilemmomas (≥3, at least one biopsy proven) |

| Acral keratoses (≥3 palmoplantar keratotic pits and/or acral hyperkeratotic papules) |

| Mucocutaneous neuromas (≥3) |

| Oral papillomas (particularly on tongue and gingiva), multiple (≥3) OR biopsy proven OR dermatologist diagnosed |

| Minor criteria |

| Autism spectrum disorder |

| Colon cancer |

| Esophageal glycogenic acanthosis (≥3) |

| Lipomas (≥ 3) |

| intellectual disability (i.e., IQ ≤ 75) |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

| Testicular lipomatosis |

| Thyroid cancer (papillary or follicular variant of papillary) |

| Thyroid structural lesions (e.g., adenoma, multinodular goiter) |

| Vascular anomalies (including multiple intracranial developmental venous anomalies) |

Screening

The management of Cowden syndrome centers on the early detection and prevention of cancer types that are known to occur as part of this syndrome.[1] Specific screening guidelines for Cowden syndrome patients have been published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).[11] Surveillance focuses on the early detection of breast, endometrial, thyroid, colorectal, renal, and skin cancer.[11] See below for a complete list of recommendations from the NCCN:

| Women | Men and Women |

|---|---|

| Breast awareness starting at age 18 years of age | Annual comprehensive physical exam starting at 18 years of age or 5 years before the youngest age of diagnosis of a component cancer in the family (whichever comes first), with particular attention to breast and thyroid exam |

| Clinical breast exam, every 6–12 month, starting at age 25 y or 5–10 y before the earliest known breast cancer in the family | Annual thyroid starting at age 18 y or 5–10 y before the earliest known thyroid cancer in the family, whichever is earlier |

| Annual mammography and breast MRI screening starting at age 30–35 y or individualized based on earliest age of onset in family | Colonoscopy, starting at age 35 y, then every 5 y or more frequently if patient is symptomatic or polyps found |

| For endometrial cancer screening, encourage patient education and prompt response to symptoms and participation in a clinical trial to determine the effectiveness or necessity of screening modalities | Consider renal ultrasound starting at age 40 y, then every 1–2 y |

| Discuss risk-reducing mastectomy and hysterectomy and counsel regarding degree of protection, extent of cancer risk and reconstruction options | Dermatological management may be indicated for some patients |

| Address psychosocial, social, and quality-of-life aspects of undergoing risk-reducing mastectomy and/or hysterectomy | Consider psychomotor assessment in children at diagnosis and brain MRI if there are symptoms |

| Education regarding the signs and symptoms of cancer |

Treatment

Malignancies that occur in Cowden syndrome are usually treated in the same fashion as those that occur sporadically in patients without a hereditary cancer syndrome.[12] Two notable exceptions are breast and thyroid cancer.[12] In Cowden syndrome patients with a first-time diagnosis of breast cancer, treatment with mastectomy of the involved breast as well as prophylactic mastectomy of the uninvolved contralateral breast should be considered.[1] In the setting of thyroid cancer or a follicular adenoma, a total thyroidectomy is recommended even in cases where it appears that only one lobe of the thyroid is affected.[12] This is due to the high likelihood of recurrence as well as the difficulty in distinguishing a benign from malignant growth with a hemithyroidectomy alone.[12]

The benign mucocutaneous lesions observed in Cowden syndrome are typically not treated unless they become symptomatic or disfiguring.[12] If this occurs, numerous treatment options, including topical agents, cryosurgery, curettage, laser ablation, and excision, may be utilized.[12]

History

Cowden Syndrome was described in 1963, when Lloyd and Dennis described a novel inherited disease that predisposed to cancer. It was named after the Cowden family, in which it was discovered. They described the various clinical features including "adenoid facies; hypoplasia of the mandible and maxilla; a high-arch palate; hypoplasia of the soft palate and uvula; microstomia; papillomatosis of the lips and oral pharynx; scrotal tongue; [and] multiple thyroid adenomas."[18]

The genetic basis of Cowden Syndrome was revealed in 1997, when germline mutations in a locus at 10q23 were associated to the novel PTEN tumor suppressor.[19]

References

- Mester J, Eng C (January 2015). "Cowden syndrome: recognizing and managing a not-so-rare hereditary cancer syndrome". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 111 (1): 125–30. doi:10.1002/jso.23735. PMID 25132236. S2CID 33056798.

- Gosein MA, Narinesingh D, Nixon CA, Goli SR, Maharaj P, Sinanan A (August 2016). "Multi-organ benign and malignant tumors: recognizing Cowden syndrome: a case report and review of the literature". BMC Research Notes. 9: 388. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-2195-z. PMC 4973052. PMID 27488391.

- Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, Pho L, Shannon KM, Swisher E (November 2013). "Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 105 (21): 1607–16. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt277. PMID 24136893.

- Habif TP (2016). Clinical dermatology : a color guide to diagnosis and therapy (Sixth ed.). [St. Louis, Mo.] ISBN 978-0-323-26183-8. OCLC 911266496.

- Porto AC, Roider E, Ruzicka T (2013). "Cowden Syndrome: report of a case and brief review of literature". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 88 (6 Suppl 1): 52–5. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132578. PMC 3876002. PMID 24346879.

- Callen JP (9 May 2016). Dermatological signs of systemic disease (Fifth ed.). Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-323-35829-3. OCLC 947111367.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, Ko CJ (2014). Dermatology essentials. Oxford. ISBN 9781455708413. OCLC 877821912.

- Kasper D, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (2015-04-08). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 19/E (Vol.1 & Vol.2) (19th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 2344. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- Niederhuber JE, Armitage JO, Doroshow JH, Kastan MB, Tepper JE, Abeloff MD. Abeloff's clinical oncology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455728657. OCLC 857585932.

- Ma, Huiying; Brosens, Lodewijk A. A.; Offerhaus, G. Johan A.; Giardiello, Francis M.; de Leng, Wendy W. J.; Montgomery, Elizabeth A. (January 2018). "Pathology and genetics of hereditary colorectal cancer". Pathology. 50 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2017.09.004. ISSN 1465-3931. PMID 29169633.

- Jelsig AM, Qvist N, Brusgaard K, Nielsen CB, Hansen TP, Ousager LB (July 2014). "Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a review". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 9: 101. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-9-101. PMC 4112971. PMID 25022750.

- Gustafson S, Zbuk KM, Scacheri C, Eng C (October 2007). "Cowden syndrome". Seminars in Oncology. 34 (5): 428–34. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.07.009. PMID 17920899.

- Pilarski R (February 2009). "Cowden syndrome: a critical review of the clinical literature". Journal of Genetic Counseling. 18 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1007/s10897-008-9187-7. PMID 18972196. S2CID 5671218.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, Perkins JA (2014). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (Ninth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455726134. OCLC 879416939.

- Turnpenny, Peter D.; Ellard, Sian (2012). Emery's elements of medical genetics (14th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780702040436. OCLC 759158627.

- Yehia, Lamis; Niazi, Farshad; Ni, Ying; Ngeow, Joanne; Sankunny, Madhav; Liu, Zhigang; Wei, Wei; Mester, Jessica; Keri, Ruth; Zhang, Bin; Eng, Charis (5 November 2015). "Germline Heterozygous Variants in SEC23B Are Associated with Cowden Syndrome and Enriched in Apparently Sporadic Thyroid Cancer". Am J Hum Genet. 97 (5): 661–676. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.10.001. PMC 4667132. PMID 26522472.

- Yehia, Lamis; Jindal, Supriya; Komar, Anton; Eng, Charis (15 September 2018). "Non-canonical role of cancer-associated mutant SEC23B in the ribosome biogenesis pathway". Hum Mol Genet. 27 (18): 3154–3164. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddy226. PMC 6121187. PMID 29893852.

- LLOYD, KENNETH M. (1963-01-01). "Cowden's Disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 58 (1): 136–142. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-58-1-136. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 13931122.

- Liaw, Danny; Marsh, Debbie J.; Li, Jing; Dahia, Patricia L. M.; Wang, Steven I.; Zheng, Zimu; Bose, Shikha; Call, Katherine M.; Tsou, Hui C.; Peacoke, Monica; Eng, Charis (May 1997). "Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome". Nature Genetics. 16 (1): 64–67. doi:10.1038/ng0597-64. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 9140396. S2CID 33101761.

Further reading

- de Jong MM, Nolte IM, te Meerman GJ, van der Graaf WT, Oosterwijk JC, Kleibeuker JH, Schaapveld M, de Vries EG (April 2002). "Genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2 involved in breast cancer susceptibility". Journal of Medical Genetics. 39 (4): 225–42. doi:10.1136/jmg.39.4.225. PMC 1735082. PMID 11950848.

- Eng C (November 2000). "Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up: revised diagnostic criteria". Journal of Medical Genetics. 37 (11): 828–30. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.11.828. PMC 1734465. PMID 11073535.

- Kelly P (October 2003). "Hereditary breast cancer considering Cowden syndrome: a case study". Cancer Nursing. 26 (5): 370–5. doi:10.1097/00002820-200310000-00005. PMID 14710798. S2CID 8896768.

- Pilarski R, Eng C (May 2004). "Will the real Cowden syndrome please stand up (again)? Expanding mutational and clinical spectra of the PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome". Journal of Medical Genetics. 41 (5): 323–6. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.018036. PMC 1735782. PMID 15121767.

- Waite KA, Eng C (April 2002). "Protean PTEN: form and function". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (4): 829–44. doi:10.1086/340026. PMC 379112. PMID 11875759.

- Zhou XP, Waite KA, Pilarski R, Hampel H, Fernandez MJ, Bos C, Dasouki M, Feldman GL, Greenberg LA, Ivanovich J, Matloff E, Patterson A, Pierpont ME, Russo D, Nassif NT, Eng C (August 2003). "Germline PTEN promoter mutations and deletions in Cowden/Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome result in aberrant PTEN protein and dysregulation of the phosphoinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (2): 404–11. doi:10.1086/377109. PMC 1180378. PMID 12844284.