Black Death migration

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people in Eurasia, and peaking in Eurasia from 1321 to 1353. Its migration followed the sea and land trading routes of the medieval world. This migration has been studied for centuries as an example of how the spread of contagious diseases is impacted by human society and economics.

Plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, and is enzootic (commonly present) in populations of ground rodents in Central Asia. While initial phylogenetic studies suggested that the plague bacillus evolved 2,000 years ago near China, specifically in the Tian Shan mountains on the border between modern-day China and Kyrgyzstan,[1][2][3] this view has been contested by recent molecular studies which have indicated that the plague was present in Scandinavia 3,000 years earlier.[4] Likewise, the immediate origins of the Black Death are also uncertain. The pandemic has often been assumed to have started in China, but lack of physical and specific textual evidence for it in 14th century China has resulted in continued disputes on the origin to this day.[5] Other theories of origin place the first cases in the steppes of Central Asia or the Near East.[6] Historians Michael W. Dols and Ole Benedictow argue that the historical evidence concerning epidemics in the Mediterranean and specifically the Plague of Justinian point to a probability that the Black Death originated in Central Asia, where it then became entrenched among the rodent population.[7][8]

According to eastern origin theories, it has been assumed that the plague transferred from Central Asia east and west along the Silk Road, by Mongol armies and traders making use of the opportunities of free passage within the Mongol Empire offered by the Pax Mongolica. It was reportedly first introduced to Europe when Mongols lobbed plague-infected corpses during the siege of the city of Caffa in the Crimea in 1347.[9] The Genoese traders fled, bringing the plague by ship into Sicily and Southern Europe, whence it spread.[10] However even the Silk Road spread theory is disputed, as others point out that the Pax Mongolica had already broken down by 1325, when Western and Persian traders found it difficult to conduct trade in the region, and impossible by 1340.[11]

Preexisting conditions

Regardless of its origin, it is clear that several preexisting conditions such as war, famine, and weather contributed to the severity of the Black Death. In China, the 13th-century Mongol conquest disrupted farming and trading, and led to widespread famine. The population dropped from approximately 120 to 60 million.[12] In Northern Europe, new technological innovations such as the heavy plough and the three-field system were not as effective in clearing new fields for harvest as they were in the Mediterranean because the north had poor, clay-like soil.[13] Food shortages and skyrocketing prices were a fact of life for as much as a century before the plague. Wheat, oats, hay, and consequently livestock, were all in short supply, and their scarcity resulted in hunger and malnutrition. The result was a mounting human vulnerability to disease due to weakened immune systems.

The Medieval Warm Period ended in Europe sometime in the 13th century, bringing harsher winters and reduced harvests. Heavy rains in late 1314 began several years of cold and wet winters. The already weak harvests of the north suffered. In the years 1315 to 1317, a catastrophic famine, known as the Great Famine, struck much of Northwest Europe. The famine came about as the result of a large population growth in the previous centuries, with the result that, in the early 14th century the population exceeded the number that could be sustained by farming.[13] The Great Famine was the worst in European history, reducing the population by at least ten percent.[14] Records recreated from dendrochronological studies show a hiatus in building construction during the period, as well as a deterioration in climate.[15] This was the economic and social situation in which the predictor of the coming disaster, a typhoid epidemic, emerged. Many thousands died in populated urban centres, most significantly Ypres. In 1318 a pestilence of unknown origin, sometimes identified as anthrax, affected the animals of Europe, notably sheep and cattle, further reducing the food supply and income of the peasantry.

The European economy entered a vicious circle in which hunger and chronic, low-level debilitating disease reduced the productivity of labourers, and so the grain output was reduced, causing grain prices to increase. This situation was worsened when landowners and monarchs like Edward III of England (r. 1327–1377) and Philip VI of France (r. 1328–1350), out of a fear that their comparatively high standard of living would decline, raised the fines and rents of their tenants.[14] Standards of living then fell drastically, diets grew more limited, and Europeans as a whole experienced more health problems.

Possible Asian outbreak

China

For years it was common for Europeans to assume that the Black Death originated in China. Charles Creighton, in his History of Epidemics in Britain (1891), summarizes the tendency to retrospectively describe the origins of the Black Death in China despite lack of evidence for it: "In that nebulous and unsatisfactory state the old tradition of the Black Death originating in China has remained to the present hour".[16] There were records of epidemics from 1308 to 1347 but the loss of life is "clearly assigned to floods and famines, with their attendant sickness."[17] In 1308, there was a plague or malignant fever in Jiangxi and Zhejiang following floods, locusts, and failure of crops. In 1313 there was an epidemic in the capital.[18] According to Creighton, Chinese records of pestilence and epidemics in the 14th century suggest nothing more than typhus, and the dates of major Chinese outbreaks of epidemic disease, marked as "great pestilence" or "great plague" from 1352 to 1363, post-date the European epidemic by several years.[17]

The suggestion is that the soil of China may not have felt the full effects of the plague virus, originally engendered thereon, until some few years after the same had been carried to Europe, having produced there within a short space of time the stupendous phenomenon of the Black Death. If there be something of a paradox in that view, it is the facts themselves that refuse to fall into what might be thought the natural sequence.[17]

— Charles Creighton

Three waves of epidemics occurred in the last years of the Yuan dynasty: 1331-34 spreading from Hebei to Hunan, in 1344–46 in coastal Fujian and Shandong, and in the 1350s throughout northern and central China. The epidemic of 1331-34 recorded a death toll of 13 million people by 1333. The epidemic of 1344-46 was called a "great pestilence."[19] On the heels of the European epidemic, a widespread disaster occurred in China during 1353–1354. Chinese accounts of this wave of the disease record a spread to eight distinct areas: Hubei, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Hunan, Guangdong, Guangxi, Henan, and Suiyuan.[lower-alpha 1] More than two thirds of the population in part of Shanxi died and six or seven out of ten in Hubei died. Epidemics afflicted various provinces from 1356 to 1360. In 1358, over 200,000 in Shanxi and Hubei died.[20] In Hebei and Shandong, the population fell from 3.3 million in 1207 to 1.1 million in 1393, however the population in the southern Yangzi region continued to grow from 1210 to the mid-1350s and only fell by less than 10 percent by 1381.[21]

Research on the Delhi Sultanate and the Yuan Dynasty shows no evidence of any serious epidemic in fourteenth-century India and no specific evidence of plague in fourteenth-century China, suggesting that the Black Death may not have reached these regions.[22] According to Dr Mark Achtman, the Black Death evolved in China over 2,600 years but the dating of the plague suggests that it was not carried along the Silk Road and its appearance there probably postdates the European outbreak. There is also no physical or specific textual evidence for the Black Death in 14th century China. It's speculated that rats aboard Zheng He's ships in the 15th century may have carried the plague to Southeast Asia, India, and Africa.[5][23] In the present state of research, it is unclear whether 13th-century epidemics in China were in fact outbreaks of the Black Death.[24] According to George D. Sussman, although a case for the Black Death in China is stronger than India, there are several reasons to question it. One, it did not seem to spread throughout all of China but only in certain provinces and regions, unlike in Europe, despite its relatively dense population and integrated economy. Two, there are no descriptions of the symptoms of the Black Death. Three, the timing does not seem to coincide with the spread of the Black Death elsewhere.[11]

What we know, then, is that major, highly lethal epidemics afflicted China in the 1330s–50s and undoubtedly contributed to a catastrophic population collapse that began in the thirteenth century and continued, or perhaps rebounded, in the mid-fourteenth century. Although we know nothing of the clinical details of the disease or diseases behind the epidemics, we do know that they began in the northeast (Hebei and Shandong) and spread down the coast and inland to the central provinces. We hear only scant references to these epidemics in the south and none in the southwest or west. Of course, that may be because those area were remote from the capital and sparsely populated compared to the northeastern and central provinces. If the disease afflicting China in the mid-fourteenth century was the plague, which was ravaging the Middle East and Europe from 1347 onward, it probably entered China from the Mongolian steppes north of Hebei and not from the Yunnan focus in the far southwest.[11]

— George D. Sussman

Bubonic plague in its endemic form was mentioned for the first time in Chinese sources in 610 and 652, which if presumed to be in connection to the first plague pandemic, would have required human spread for a realistic spread rate from west to east over 5,500 km. In 610, Chao Yuanfang mentioned a "malignant bubo" "coming on abruptly with high fever together with the appearance of a bundle of nodes beneath the tissues."[25] Sun Simo, who died in 652, also mentioned a "malignant bubo" and plague that was common in Guangdong but was rare in interior provinces. Benedictow believes this indicates the spread of an offshoot of the first plague pandemic which reached Chinese territory by 600.[26]

The earliest Chinese description of the Black Death comes from a local gazetteer from Shanxi in 1644: "In the autumn there was a great epidemic. The victim first developed a hard lump below the armpits or between the thighs or else coughed thin blood and died before they had time to take medicine. Even friends and relations did not dare to ask after the sick or come with their condolences. There were whole families wiped out with none to bury them."[11] The Customs Service list described it as a "Great pestilence in Lu-an" where "Those attacked had hard lumps grow on the neck or arm, like clotted blood. Whole families perished. In some cases the victims spat blood suddenly, and expired."[11] This coincided with two epidemics from 1586 to 1589 and 1639–44 that have been characterized as the most deadly in Chinese history.[11] Even then the epidemics do not seem to have behaved the same as in Europe. The epidemics in 17th century China were preceded by huge die offs in the rodent population and took decades to spread from province to province and never spread throughout the whole country, ultimately killing less than 5% of the population.[11]

India

It has been debated whether or not the Black Death occurred in India.[27]

The sultan of the Delhi Sultanate, Muhammad bin Tughluq, made a military campaign toward the South of India in 1334–1335.[27] The military expedition was suddenly interrupted when an epidemic started to spread within his army to such an extent that the whole expedition had to be stopped, and the army returned to Delhi.[27] When the army returned to Delhi, only a third of the soldiers were reportedly left.[27] Due to the fragmentary sources available, it is not known what illness this was and if it was the same as the Black Death.[27] It is known, however, that the Sultan of Delhi recruited many mercenaries from Central Asia in to his army, and since the Black Death is known to have been present in Central Asia, it is considered theoretically possible that the plague could have been carried to India by them.[27]

Whether the Black Death occurred in India is not known, but it is regarded as a possibility and a possible contributor to the sudden decrease in power and expansion of the Delhi Sultanate in this time period.[27]

European outbreak

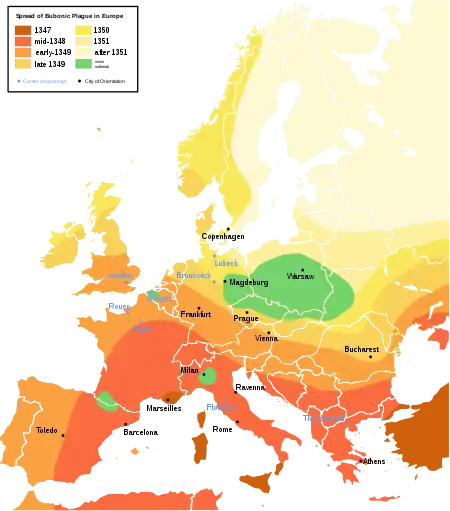

In 1345 the Mongols under Khan Jani Berg of the Golden Horde besieged Caffa. Suffering from an outbreak of black plague, the Mongols placed plague-infected corpses in catapults and threw them into the city. In October 1347, a fleet of Genoese trading ships fleeing Caffa reached the port of Messina in Sicily.[28] By the time the fleet reached Messina, all the crew members were either infected or dead. It is presumed that the ships also carried infected rats and/or fleas. Some ships were found grounded on shorelines, with no one aboard remaining alive.

Looting of these lost ships also helped spread the disease. From there, the plague spread to Genoa and Venice by the turn of 1347–1348, spreading across Italy.

From Italy the disease spread northwest across Europe, striking France, the Crown of Aragon, the Crown of Castile, Portugal and England by June 1348, then turned and spread east through Germany and Scandinavia from 1348 to 1350. It was introduced in Norway in 1349 when a ship landed at Askøy, then proceeded to spread to Bjørgvin (modern Bergen). From Norway it continued to Sweden, by which point it had already spread around Denmark.

Finally it spread to north-eastern Russia in 1351; however, the plague largely spared some parts of Europe, including the Kingdom of Poland, isolated parts of Belgium and the Netherlands, Milan and the modern-day France-Spain border.

At Siena, Agnolo di Tura wrote:

"They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ... ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura … buried my five children with my own hands … And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world."[29]

Middle Eastern outbreak

The plague struck various countries in the Middle East during the pandemic, leading to serious depopulation and permanent change in both economic and social structures. As it spread to western Europe, the disease also entered the region from southern Russia. By autumn 1347, the plague reached Alexandria in Egypt, probably through the port's trade with Constantinople, and ports on the Black Sea. During 1348, the disease travelled eastward to Gaza, and north along the eastern coast to cities including Ashkelon, Acre, Jerusalem, Sidon, Damascus, Homs, and Aleppo. In 1348–49, the disease reached Antioch. The city's residents fled to the north, most of them dying during the journey, but the infection had been spread to the people of Asia Minor.[30]

Mecca became infected in 1349. During the same year, records show the city of Mawsil (Mosul) suffered a massive epidemic, and the city of Baghdad experienced a second round of the disease. In 1351, Yemen experienced an outbreak of the plague. This coincided with the return of King Mujahid of Yemen from imprisonment in Cairo. His party may have brought the disease with them from Egypt.[30]

Recurrence

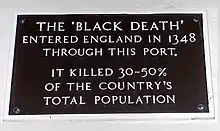

In England, in the absence of census figures, historians propose a range of pre-incident population figures from as high as 7 million to as low as 4 million in 1300, and a post-incident population figure as low as 2 million.[31] By the end of 1350 the Black Death had subsided, but it never really died out in England over the next few hundred years: there were further outbreaks in 1361–62, 1369, 1379–83, 1389–93, and throughout the first half of the 15th century.[32] The plague often killed 10% of a community in less than a year—in the worst epidemics, such as at Norwich in 1579 and Newcastle in 1636, as many as 30 or 40%. The most general outbreaks in Tudor and Stuart England, all coinciding with years of plague in Germany and the Low Countries, seem to have begun in 1498, 1535, 1543, 1563, 1589, 1603, 1625, and 1636.[33]

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean throughout the 14th to 18th centuries, and still occurs in isolated cases today.

The plague of 1575–77 claimed some 50,000 victims in Venice. In 1634, an outbreak of plague killed 15,000 Munich residents.[34] Late outbreaks in central Europe include the Italian Plague of 1629–1631, which is associated with troop movements during the Thirty Years' War, and the Great Plague of Vienna in 1679. About 200,000 people in Moscow died of the disease from 1654 to 1656.[35] Oslo was last ravaged in 1654.[36] In 1656 the plague killed about half of Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.[37] Amsterdam was ravaged in 1663–1664, with a mortality given as 50,000.[38]

The Great Plague of London in 1665–1666 is generally recognized as one of the last major outbreaks.[39]

A plague epidemic known as the Great Northern War plague outbreak, that followed the Great Northern War (1700–1721, Sweden v. Russia and allies) wiped out almost 1/3 of the population in the region. An estimated one-third of East Prussia's population died in the plague of 1709–1711.[40] The plague of 1710 killed two-thirds of the inhabitants of Helsinki.[41] An outbreak of plague between 1710 and 1711 claimed a third of Stockholm's population.[42]

During the Great Plague of 1738, the epidemic struck again, this time in Eastern Europe, spreading from Ukraine to the Adriatic Sea, then onwards by ship to infect some in Tunisia. The destruction in several cities in what is now Romania (such as Timișoara) was formidable, claiming tens of thousands of lives.

Notes

- Suiyuan was a historical Chinese province that now forms part of Hebei and Inner Mongolia.

References

- Morelli; et al. (2010). "Phylogenetic diversity and historical patterns of pandemic spread of Yersinia pestis". Nat. Genet. 42 (12): 1140–1143. doi:10.1038/ng.705. PMC 2999892. PMID 21037571.

- "Origins of the Black Death Traced Back to China, Gene Sequencing Has Revealed". November 2010.

- Eroshenko GA, Nosov NY, Krasnov YM, Oglodin YG, Kukleva LM, Guseva NP, et al. (2017) Yersinia pestis strains of ancient phylogenetic branch 0.ANT are widely spread in the high-mountain plague foci of Kyrgyzstan. PLoS ONE 12(10): e0187230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187230

- Rascovan, Nicolas; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Kristiansen, Kristian; Nielsen, Rasmus; Willerslev, Eske; Desnues, Cristelle; Rasmussen, Simon (10 January 2019). "Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline". Cell. 176 (2): 295–305.

- Moore, Malcolm (1 November 2010). "Black Death may have originated in China". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Philip Slavin, "Death by the Lake: Mortality Crisis in Early Fourteenth-Century Central Asia", Journal of Interdisciplinary History 50/1 (Summer 2019): 59–90. https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/jinh_a_01376

- Michael W. Dols, "The Second Plague Pandemic and Its Recurrences in the Middle East: 1347–1894" Journal of the Economic Social History of the Orientvol. 22 no. 2 (May 1979), 170–171.

- Benedictow, Ole Jørgen (2004). Black Death 1346–1353: The Complete History. pp. 48–51. ISBN 978-1-84383-214-0.

- Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 8 (9), 971–975. .

- "Channel 4—History—The Black Death". Channel4.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=lg_pubs

- Ping-ti Ho, "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33–53.

- Judith M. Bennett & C. Warren Hollister (2006). Medieval Europe: A Short History. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 326. ISBN 978-0-07-295515-6. OCLC 56615921.

- Bennett and Hollister, Medieval Europe, p. 327

- Baillie, Mike (1997). A Slice Through Time. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7134-7654-5.

- Charles Creighton's A History of Epidemics in Britain, Cambridge: At the University Press. 1891. pg 143.

- Charles Creighton's A History of Epidemics in Britain, Cambridge: At the University Press. 1891. pg 153.

- Charles Creighton's A History of Epidemics in Britain, Cambridge: At the University Press. 1891. pg 151.

- Sussman 2011, p. 347.

- Sussman 2011, p. 348.

- Sussman 2011, p. 350.

- Sussman 2011.

- Benedictow 2004, p. 48-49.

- Sussman, George D. (Fall 2011). "Was the black death in India and China?". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 85 (3): 319–55. doi:10.1353/bhm.2011.0054. PMID 22080795. S2CID 41772477.

- Benedictow 2021, p. 129.

- Benedictow 2021, p. 130.

- Harrison, Dick, Stora döden: den värsta katastrof som drabbat Europa, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2000 ISBN 91-7324-752-9

- "At the beginning of October, in the year of the incarnation of the Son of God 1347, twelve Genoese galleys were fleeing from the vengeance which our Lord was taking on account of their nefarious deeds and entered the harbour of Messina. In their bones they bore so virulent a disease that anyone who only spoke to them was seized by a mortal illness and in no manner could evade death. ...Not only all those who had speech with them died, but also those who had touched or used any of their things. When the inhabitants of Messina discovered that this sudden death emanated from the Genoese ships they hurriedly ordered them out of the harbor and town. But the evil remained and caused a fearful outbreak of death." Michael Platiensis (1357), quoted in Johannes Nohl (1926). The Black Death, trans. C.H. Clarke. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., pp. 18–20.

- "plague readings". U.arizona.edu. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Kohn, George C. (1998). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence : from ancient times to the present (2008 ed.). New York: Infobase. p. 262. ISBN 9781438129235.

- Secondary sources such as the Cambridge History of Medieval England often contain discussions of methodology in reaching these figures that are necessary reading for anyone wishing to understand this controversial episode in more detail.

- "BBC—History—Black Death". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "BBC—Radio 4 Voices of the Powerless—29 August 2002 Plague in Tudor and Stuart Britain". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Texas Department of State Health Services, History of Plague". Dshs.state.tx.us. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Genesis of the Anti-Plague System: The Tsarist Period" (PDF). James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Øivind Larsen. "DNMS.NO : Michael : 2005 : 03/2005 : Book review: Black Death and hard facts". Dnms.no. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Naples in the 1600s". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- "Buboni PlagueEuropeFlorence". Mindquestacademy.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- "The London Plague 1665". Britainexpress.com. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Online Library of Liberty—BOOK II, CHAPTER XI: OF THE MODE IN WHICH THE QUANTITY OF THE PRODUCT AFFECTS POPULATION—A Treatise on Political Economy". Oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Ruttopuisto—Plague Park". Tabblo.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "Historical facts about Stockholm, capital of Sweden". Enjoystockholm.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

Bibliography

- Benedictow, Ole J. (2021), The Complete History of the Black death, The Boydell Press

- von Glahn, Richard (2016), The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century