Consequences of the Black Death

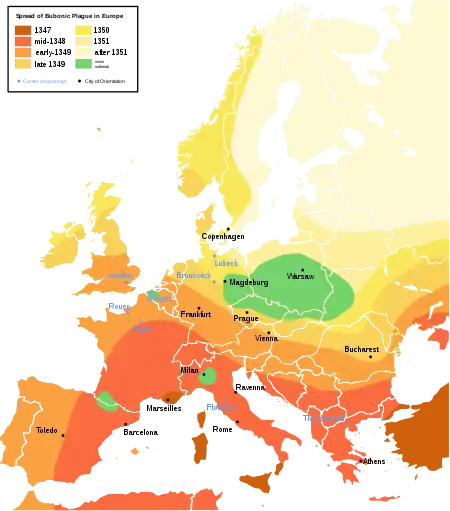

The Black Death peaked in Europe between 1348 and 1350 with an estimated one-third of the continent's population ultimately succumbing to the disease. Often simply referred to as "The Plague", the Black Death had both immediate and long-term effects on human population across the world as one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. These included a series of biological, social, economic, political and religious upheavals which had profound effects on the course of world history, especially the history of Europe. Symptoms of the bubonic plague included painful and enlarged or swollen lymph nodes, headaches, chills, fatigue, vomiting, and fevers, and within 3–5 days, 80% of the victims would be dead.[1] Historians estimate that it reduced the total world population from 475 million to between 350 and 375 million. In most parts of Europe, it took nearly 80 years for population sizes to recover, and in some areas more than 150 years.

From the perspective of many of the survivors, the effect of the plague may have been ultimately favorable, as the massive reduction of the workforce meant their labor was suddenly in higher demand. R. H. Hilton has argued that those English peasants who survived found their situation to be much improved. For many Europeans, the 15th century was a golden age of prosperity and new opportunities. The land was plentiful, wages high, and serfdom had all but disappeared. A century later, as population growth resumed, the lower classes once again faced deprivation and famine.[2][3][4]

Death toll

Figures for the death toll vary widely by area and from source to source, and estimates are frequently revised as historical research brings new discoveries to light. Most scholars estimate that the Black Death killed up to 75 million people[5] in the 14th century, at a time when the entire world population was still less than 500 million.[6][7] Even where the historical record is considered reliable, only rough estimates of the total number of deaths from the plague are possible.

Europe

Europe suffered an especially significant death toll from the plague. Modern estimates range between roughly one-third and one-half of the total European population in the five-year period of 1347 to 1351 died, during which the most severely affected areas may have lost up to 80% of the population.[8] Contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart estimated the toll to be one-third, which modern scholars consider less an accurate assessment than an allusion to the Book of Revelation meant to suggest the scope of the plague.[9] Deaths were not evenly distributed across Europe, with some areas affected very little while others were all but entirely depopulated.[10]

The Black Death hit the culture of towns and cities disproportionately hard, although rural areas (where most of the population lived at the time) were also significantly affected. Larger cities were the worst off, as population densities and close living quarters made disease transmission easier. Cities were also strikingly filthy, infested with lice, fleas, and rats, and subject to diseases caused by malnutrition and poor hygiene.[11] The population of the city of Florence was reduced from 110,000 to 120,000 inhabitants in 1338 to 50,000 in 1351. In the cities of Hamburg and Bremen, 60–70% of the inhabitants died. In Provence, Dauphiné, and Normandy, historians observe a decrease of 60% of fiscal hearths. In some regions, two-thirds of the population was annihilated. In the town of Givry in the Bourgogne region of France, the local friar, who used to note 28–29 funerals a year, recorded 649 deaths in 1348, half of them in September. About half the population of Perpignan died over the course of several months (only two of the eight physicians survived the plague). Over 60% of Norway's population died between 1348 and 1350.[12] London may have lost two-thirds of its population during the 1348–49 outbreak;[13] England as a whole may have lost 70% of its population, which declined from 7 million before the plague to 2 million in 1400.[14]

Some places, including the Kingdom of Poland, parts of Hungary, the Brabant region, Hainaut, and Limbourg (in modern Belgium), as well as Santiago de Compostela, were unaffected for unknown reasons. Some historians[15] have assumed that the presence of resistant blood groups in the local population helped them resist infection, although these regions were touched by the second plague outbreak in 1360–1363 (the "little mortality") and later during the numerous resurgences of the plague (in 1366–1369, 1374–75, 1400, 1407, etc.). Other areas which escaped the plague were isolated in mountainous regions (e.g. the Pyrenees).

All social classes were affected, although the lower classes, living together in unhealthy places, were most vulnerable. Alfonso XI of Castile and Joan of Navarre (daughter of Louis X le Hutin and Margaret of Burgundy) were the only European monarchs to die of the plague, but Peter IV of Aragon lost his wife, his daughter, and a niece in six months. Joan of England, daughter of Edward III, died in Bordeaux on her way to Castile to marry Alfonso's son Pedro. The Byzantine Emperor lost his son, while in the Kingdom of France, Bonne of Luxembourg, the wife of the future John II of France, died of the plague.

Asia

Estimates of the demographic effect of the plague in Asia are based on population figures during this time and estimates of the disease's toll on population centers. The most severe outbreak of plague, in the Chinese province of Hubei in 1334, claimed up to 80% of the population. China had several epidemics and famines from 1200 to the 1350s and its population decreased from an estimated 125 million to 65 million in the late 14th century.[16][17][18]

The precise demographic effect of the disease in the Middle East is very difficult to calculate. Mortality was particularly high in rural areas, including significant areas of Gaza and Syria. Many rural people fled, leaving their fields and crops, and entire rural provinces are recorded as being totally depopulated. Surviving records in some cities reveal a devastating number of deaths. The 1348 outbreak in Gaza left an estimated 10,000 people dead, while Aleppo recorded a death rate of 500 per day during the same year. In Damascus, at the disease's peak in September and October 1348, a thousand deaths were recorded every day, with overall mortality estimated at between 25 and 38 percent. Syria lost a total of 400,000 people by the time the epidemic subsided in March 1349. In contrast to some higher mortality estimates in Asia and Europe, scholars such as John Fields of Trinity College in Dublin believe the mortality rate in the Middle East was less than one-third of the total population, with higher rates in selected areas.

Social, environmental, and economic effects

Because 14th-century healers were at a loss to explain the cause of the Black Death, many Europeans gave supernatural forces, earthquakes and malicious conspiracies, among other things, as possible reasons for the plague's emergence.[19] No one in the 14th century considered rat control a way to ward off the plague, and people began to believe only God's anger could produce such horrific displays of suffering and death. Giovanni Boccaccio, an Italian writer and poet of the era, questioned whether it was sent by God for their correction, or if it came through the influence of the heavenly bodies.[20] Christians accused Jews of poisoning public water supplies, alleging Jews were making an effort to ruin European civilization. The spreading of this rumor led to complete destruction of entire Jewish towns. In February 1349, 2,000 Jews were murdered in Strasbourg. In August of the same year, the Jewish communities of Mainz and Cologne were murdered.[21]

Where government authorities were concerned, most monarchs instituted measures that prohibited exports of foodstuffs, condemned black market speculators, set price controls on grain, and outlawed large-scale fishing. At best, these proved mostly unenforceable; at worst, they contributed to a continent-wide downward spiral. The hardest-hit lands, like England, were unable to buy grain abroad from France because of the prohibition, and from most of the rest of the grain producers, because of crop failures from shortage of labour. Any grain which could be shipped was eventually taken by pirates or looters to be sold on the black market. Meanwhile, many of the largest countries, most notably England and Scotland, had been at war, using up much of their treasury and exacerbating inflation. In 1337, on the eve of the first wave of the Black Death, England and France went to war in what would become known as the Hundred Years' War. Malnutrition, poverty, disease and hunger coupled with war, growing inflation, and other economic concerns made Europe in the mid-14th century ripe for tragedy.

Historian Walter Scheidel contends that waves of plague following the initial outbreak of the Black Death had a leveling effect which changed the ratio of land to labour, reducing the value of the former while boosting that of the latter, which lowered economic inequality by making landowners and employers less well-off while improving the lot of the workers. He states, "the observed improvement in living standards of the laboring population was rooted in the suffering and premature death of tens of millions over the course of several generations." This leveling effect was reversed by a "demographic recovery that resulted in renewed population pressure."[22] On the other hand, in the quarter-century after the Black Death it is clear that in England, many laborers, artisans, and craftsmen, those living from money-wages alone, did suffer a reduction in real incomes owing to rampant inflation.[23] In 1357, a third of property in London was unused due to a severe outbreak in 1348–49.[13] However, for reasons still debated, population levels declined after the Black Death's first outbreak until around 1420, and did not begin to rise again until 1470, so the initial Black Death event on its own does not entirely provide a satisfactory explanation to this extended period of decline in prosperity. See Medieval demography for a more complete treatment of this issue, and current theories on why improvements in living standards took longer to evolve.

Effect on the peasantry

The great population loss brought favorable results to the surviving peasants in England and Western Europe. There was increased social mobility, as depopulation further eroded the peasants' already weakened obligations to remain on their traditional holdings. Seigneurialism never recovered. Land was plentiful, wages high, and serfdom had all but disappeared. It was possible to move about and rise higher in life. Younger sons and women especially benefited.[24] As population growth resumed, however, the peasants again faced deprivation and famine.[3][25]

In Eastern Europe, by contrast, renewed stringency of laws tied the remaining peasant population more tightly to the land than ever before through serfdom.

Furthermore, the plague's great population reduction brought cheaper land prices, more food for the average peasant, and a relatively large increase in per capita income among the peasantry, if not immediately, in the coming century. Since the plague left vast areas of farmland untended, they were made available for pasture and put more meat on the market; the consumption of meat and dairy products went up, as did the export of beef and butter from the Low Countries, Scandinavia, and northern Germany. However, the upper class often attempted to stop these changes, initially in Western Europe, and more forcefully and successfully in Eastern Europe, by instituting sumptuary laws. These regulated what people (particularly of the peasant class) could wear, so that nobles could ensure that peasants did not begin to dress and act as a higher class member with their increased wealth. Another tactic was to fix prices and wages, so that peasants could not demand more with increasing value. In England, the Statute of Labourers 1351 was enforced, meaning, no peasant could ask for more wages than in 1346.[26] This was met with varying success depending on the amount of rebellion it inspired; such a law was one of the causes of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England.

The rapid development of the use was probably one of the consequences of the Black Death, during which many landowning nobility died, leaving their realty to their widows and minor orphans.

Effect on urban workers

In the wake of the drastic population decline brought on by the plague, wages shot up and labourers could move to new localities in response to wage offers. Local and royal authorities in Western Europe instituted wage controls. These governmental controls sought to freeze wages at the old levels before the Black Death. Within England, for example, the Ordinance of Labourers, enacted in 1349, and the Statute of Labourers, enacted in 1351, restricted both wage increases and the relocation of workers.[27] If workers attempted to leave their current post, employers were given the right to have them imprisoned. The statute was poorly enforced in most areas, and farm wages in England on average doubled between 1350 and 1450,[28] though they were static thereonafter, until the end of the 19th century.[29]

Cohn, comparing numerous countries, argues, that these laws were not primarily designed to freeze wages. Instead, he says, the energetic local and royal measures to control labor and artisans' prices was a response to elite fears of the greed and possible new powers of lesser classes that had gained new freedom. Cohn continues, that the laws reflect the anxiety that followed the Black Death's new horrors of mass mortality and destruction, and from elite anxiety about manifestations, such as the flagellant movement and the persecution of Jews, Catalans (in Sicily), and beggars.[30]

Labour-saving innovation

By 1200, virtually all of the Mediterranean basin and most of northern Germany had been deforested and cultivated. Indigenous flora and fauna were replaced by domestic grasses and animals, and domestic woodlands were lost. With depopulation, this process was reversed. Much of the primeval vegetation returned, and abandoned fields and pastures were reforested.[31]

The Black Death encouraged innovation of labor-saving technologies, leading to higher productivity.[32] There was a shift from grain farming to animal husbandry. Grain farming was very labor-intensive, but animal husbandry needed only a shepherd and a few dogs and pastureland.[31]

Plague brought an eventual end of Serfdom in Western Europe. The manorial system was already in trouble, but the Black Death assured its demise throughout much of western and central Europe by 1500. Severe depopulation and migration of the village to cities caused an acute shortage of agricultural laborers. Many villages were abandoned. In England, more than 1300 villages were deserted between 1350 and 1500.[31] Wages of labourers were high, but the rise in nominal wages following the Black Death was swamped by post-Plague inflation, so that real wages fell.[29]

Labor was in such a short supply that Lords were forced to give better terms of tenure. This resulted in much lower rents in western Europe. By 1500, a new form of tenure called copyhold became prevalent in Europe. In copyhold, both a Lord and peasant made their best business deal, whereby the peasant got use of the land and the Lord got a fixed annual payment, and both possessed a copy of the tenure agreement. Serfdom did not end everywhere: it lingered in parts of Western Europe and was only introduced to Eastern Europe after the Black Death.[31]

There was also a change in the inheritance law. Before the plague, only sons and especially the elder son inherited the ancestral property. Post-plague, all sons as well as daughters started inheriting property.[31]

Persecutions

Renewed religious fervor and fanaticism came in the wake of the Black Death. Some Europeans targeted "groups such as Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims",[33] lepers[33][34] and Romani, thinking that they were to blame for the crisis.

Differences in cultural and lifestyle practices also led to persecution. As the plague swept across Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half the population, Jews were taken as scapegoats, in part because better hygiene among Jewish communities and isolation in the ghettos meant that Jews were less affected.[35][36] Accusations spread, that Jews had caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells.[37][38] Mobs attacked Jewish settlements across Europe; by 1351, 60 major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed, and more than 350 separate massacres had occurred.

According to Joseph P. Byrne, women also faced persecution during the Black Death. Muslim women in Cairo became scapegoats when the plague struck.[39] Byrne writes, that in 1438, the sultan of Cairo was informed by his religious lawyers, that the arrival of the plague was 'Allah's punishment for the sin of fornication,' and that in accordance with this theory, a law was set in place stating that women were not allowed to make public appearances, as 'they may tempt men into sin.' Byrne describes, that this law was only lifted when "the wealthy complained that their female servants could not shop for food."[39]

Religion

The Black Death hit the monasteries very hard because of their proximity with the sick who sought refuge there. This left a severe shortage of clergy after the epidemic cycle. Eventually the losses were replaced by hastily trained and inexperienced clergy members, many of whom knew little of the rigors of their predecessors. New colleges were opened at established universities, and the training process sped up.[40] The shortage of priests opened new opportunities for laywomen to assume more extensive and more important service roles in the local parish.[41]

Flagellants practiced self-flogging (whipping of oneself) to atone for sins. The movement became popular after the Black Death.[42] It may be that the flagellants' later involvement in hedonism was an effort to accelerate or absorb God's wrath, to shorten the time with which others suffered. More likely, the focus of attention and popularity of their cause contributed to a sense that the world itself was ending and that their individual actions were of no consequence.

Reformers rarely pointed to failures on the part of the Church in dealing with the catastrophe.[43]

Cultural effect

_%252C_affresco_staccato.jpg.webp)

The Black Death had a profound effect on art and literature. After 1350, European culture in general turned very morbid. The general mood was one of pessimism, and contemporary art turned dark with representations of death. The widespread image of the "dance of death" showed death (a skeleton) choosing victims at random. Many of the most graphic depictions come from writers such as Boccaccio and Petrarch.[44] Peire Lunel de Montech, writing about 1348 in the lyric style long out of fashion, composed the following sorrowful sirventes "Meravilhar no·s devo pas las gens" during the height of the plague in Toulouse:

They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ... ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura ... buried my five children with my own hands ... And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world.[45]

Boccaccio wrote:

How many valiant men, how many fair ladies, breakfast with their kinfolk and the same night supped with their ancestors in the next world! The condition of the people was pitiable to behold. They sickened by the thousands daily, and died unattended and without help. Many died in the open street, others dying in their houses, made it known by the stench of their rotting bodies. Consecrated churchyards did not suffice for the burial of the vast multitude of bodies, which were heaped by the hundreds in vast trenches, like goods in a ship's hold and covered with a little earth.[46]

.jpg.webp)

Medicine

Although the Black Death highlighted the shortcomings of medical science in the medieval era, it also led to positive changes in the field of medicine. As described by David Herlihy in The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, more emphasis was placed on "anatomical investigations" following the Black Death.[47] How individuals studied the human body notably changed, becoming a process that dealt more directly with the human body in varied states of sickness and health. Further, at this time, the importance of surgeons became more evident.[47]

A theory put forth by Stephen O'Brien says, the Black Death is likely responsible, through natural selection, for the high frequency of the CCR5-Δ32 genetic defect in people of European descent. The gene affects T cell function, and provides protection against HIV, smallpox, and possibly plague,[48] though for the last, no explanation as to how it would do that, exists. This, however, is now challenged, given that the CCR5-Δ32 gene has been found to be just as common in Bronze Age tissue samples.[49]

Architecture

The Black Death also inspired European architecture to move in two different directions: (1) a revival of Greco-Roman styles, and (2) a further elaboration of the Gothic style.[50] Late medieval churches had impressive structures centered on verticality, where one's eye is drawn up towards the high ceiling. The basic Gothic style was revamped with elaborate decoration in the late medieval period. Sculptors in Italian city-states emulated the work of their Roman forefathers while sculptors in northern Europe, no doubt inspired by the devastation they had witnessed, gave way to a heightened expression of emotion and an emphasis on individual differences.[51] A tough realism came forth in architecture as in literature. Images of intense sorrow, decaying corpses, and individuals with faults as well as virtues emerged. North of the Alps, painting reached a pinnacle of precise realism with Early Dutch painting by artists such as Jan van Eyck (c. 1390 – 1441). The natural world was reproduced in these works with meticulous detail whose realism was not unlike photography.[52]

See also

- Economic consequences of population decline

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

References

- The Black Death Documentary, Oliver Wendell Holmes Middle School, 23 October 2015.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, "Centuries of Transition: England in the Later Middle Ages", in Richard Schlatter, ed., Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing since 1966 (Rutgers University Press, 1984), pp 43–44, 58

- R. H. Hilton, The English Peasantry in the Late Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon, 1974)

- Scheidel, Walter (2017). "Chapter 10: The Black Death". The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 291–313. ISBN 978-0691165028.

- Dunham, Will (29 January 2008). "Black death 'discriminated' between victims". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "De-coding the Black Death". BBC News. 3 October 2001. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Philipkoski, Kristen (3 October 2001). "Black Death's Gene Code Cracked". Wired. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- "The trend of recent research is pointing to a figure more like 45% to 50% of the European population dying during a four-year period. There is a fair amount of geographic variation. In Mediterranean Europe and Italy, the South of France and Spain, where plague ran for about four years consecutively, it was probably closer to 75% to 80% of the population. In Germany and England, it was probably closer to 20%." Philip Daileader, The Late Middle Ages, audio/video course produced by The Teaching Company, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59803-345-8. Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, in L'Histoire no. 310, June 2006, pp. 45–46, say "between one-third and two-thirds"; Robert Gottfried (1983). "Black Death" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, volume 2, pp. 257–267, says "between 25 and 45 percent". Daileader, as above; Barry and Gualde, as above, Gottfried, as above. Norwegian historian Ole J. Benedictow ("The Black Death: The Greatest Catastrophe Ever", History Today, Volume 55 Issue 3, March 2005; cf. Benedictow, The Black Death 1346–1353: The Complete History, Boydell Press (7 December 2012), pp. 380ff.) suggests a death rate as high as 60%, or 50 million out of 80 million inhabitants.

- Jean Froissart, Chronicles (trans. Geoffrey Brereton, Penguin, 1968, corrections 1974), p. 111.

- Joseph Patrick Byrne (2004). The Black Death. ISBN 0-313-32492-1, p. 64.

- According to Kelly (2005), "[w]oefully inadequate sanitation made medieval urban Europe so disease-ridden, no city of any size could maintain its population without a constant influx of immigrants from the countryside". The influx of new citizens facilitated the movement of the plague between communities and contributed to the longevity of the plague within larger communities. Kelly, John. The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York: HarperCollins, 2005, p. 68

- Harald Aastorp (1 August 2004). "Svartedauden Enda verre enn antatt". Forskning.no. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Kennedy, Maev (17 August 2011). "Black Death study lets rats off the hook". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- Barry and Gualde 2006.

- Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, "La peste noire : la plus grande épidémie de l'histoire" [The Black Plague: the largest epidemic in history], in L'Histoire no. 310, June 2006, pp. 45–46

- Spengler, Joseph J. (October 1962). "Review (Studies on the Population of China, 1368–1953 by Ping-Ti Ho)". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 5 (1): 112–114. doi:10.1017/s0010417500001547. JSTOR 177771. S2CID 145085710.

- Maguire, Michael (22 February 1999). "Re: How many people recovered from Black Death (Bubonic Plague)". MadSci Network. ID: 918741314.Mi. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- King, Jonathan (8 January 2005). "World's long dance with death". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Judith M. Bennett; C. Warren Hollister (2006). Medieval Europe: A Short History. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 329. ISBN 0-07-295515-5. OCLC 56615921.

- Boccaccio, Giovanni. "Boccaccio on the Plague". Virginia Tech. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016.

- Bennett and Hollister, 329–30.

- Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 292–93, 304. ISBN 978-0691165028.

- Munro 2004, p. 352.

- Jay O'Brien; William Roseberry (1991). Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and History. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-520-07018-9.

- Barbara A. Hanawalt, "centuries of Transition: England in the Later Middle Ages," in Richard Schlatter, ed., Recent Views on British History: Essays on Historical Writing since 1966 (Rutgers UP, 1984), pp. 43–44, 58

- "Statute of Labourers Act". Spartacus Educational.

- Penn, Simon A. C.; Dyer, Christopher (1990). "Wages and Earnings in Late Medieval England: Evidence from the Enforcement of the Labour Laws". The Economic History Review. 43 (3): 356–57. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1990.tb00535.x.

- Gregory Clark, "The long march of history: Farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869," Economic History Review 60.1 (2007): 97–135. online, page 36

- Munro, John H. A. (5 March 2005). "Before and After the Black Death: Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England". ideas.repec.org. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- Samuel Cohn, "After the Black Death: Labour Legislation and Attitudes Towards Labour in Late-Medieval Western Europe," Economic History Review (2007) 60#3 pp. 457–85 in JSTOR

- Gottfried, Robert S. (1983). "7". The black death: natural and human disaster in Medieval Europe (1. Free Press paperback ed.). New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-912630-4.

- "Plagued by dear labour". The Economist. London. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence, 1998, ISBN 0-691-05889-X.

- R.I. Moore The Formation of a Persecuting Society, Oxford, 1987 ISBN 0-631-17145-2

- Naomi E. Pasachoff, Robert J. Littman A Concise History of the Jewish People 2005. p. 154 "However, Jews regularly ritually washed and bathed, and their abodes were slightly cleaner than their Christian neighbors'. Consequently, when the rat and the flea brought the Black Death, Jews, with better hygiene, suffered less severely ..."

- Joseph P Byrne, Encyclopedia of the Black Death Volume 1 2012. p. 15 "Anti–Semitism and Anti–Jewish Violence before the Black Death ... Their attention to personal hygiene and diet, their forms of worship, and cycles of holidays were off-puttingly different."

- Anna Foa The Jews of Europe After the Black Death 2000 p. 146 "There were several reasons for this, including, it has been suggested, the observance of laws of hygiene tied to ritual practices and a lower incidence of alcoholism and venereal disease"

- Richard S. Levy Antisemitism 2005 p. 763 "Panic emerged again during the scourge of the Black Death in 1348, when widespread terror prompted a revival of the well poisoning charge. In areas where Jews appeared to die of the plague in fewer numbers than Christians, possibly because of better hygiene and greater isolation, lower mortality rates provided evidence of Jewish guilt."

- Joseph P. Byrne, The Black Death (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004), 108.

- Steven A. Epstein, An Economic and Social History of Later Medieval Europe, 1000–1500 (2009) p. 182

- Katherine L. French, The Good Women of the Parish: Gender and Religion After the Black Death (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2011)

- Lewis-Stempel, John (2006). England : the autobiography : 2,000 years of English history by those who saw it happen. London: Penguin. p. 76. ISBN 9780141019956.

Flagellants Come To London, Michaelmas 1349. Robert of Avesbury.

- Epstein, p. 182

- J. M. Bennett and C. W. Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), p. 372.

- "Plague readings". University of Arizona. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- Spignesi, Stephen (2002). Catastrophe!: The 100 Greatest Disasters of All Time. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. p. 1.

- David Herlihy, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), 72.

- Jefferys, Richard; Anne-Christine d'Adesky (March 1999). "Designer Genes". HIV Plus (3). ISSN 1522-3086. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Philip W. Hedrick; Brian C. Verrelli (June 2006). "'Ground truth' for selection on CCR5-Δ32". Trends in Genetics. 22 (6): 293–96. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.007. PMID 16678299.

- Bennett and Hollister, p. 374.

- Bennett and Hollister, p. 375.

- Bennett and Hollister, p. 376.

Further reading

|

|