Chorionic villus sampling

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS), sometimes called "chorionic villous sampling" (as "villous" is the adjectival form of the word "villus"),[1] is a form of prenatal diagnosis done to determine chromosomal or genetic disorders in the fetus. It entails sampling of the chorionic villus (placental tissue) and testing it for chromosomal abnormalities, usually with FISH or PCR. CVS usually takes place at 10–12 weeks' gestation, earlier than amniocentesis or percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling. It is the preferred technique before 15 weeks.[2][3]

| Chorionic villus sampling | |

|---|---|

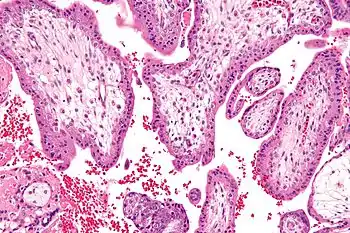

Micrograph showing chorionic villi—the tissue that is collected in CVS. H&E stain. | |

| Other names | CVS |

| ICD-10-PCS | 16603-00 |

| ICD-9-CM | 75.33 |

| MeSH | D015193 |

| MedlinePlus | 003406 |

CVS was performed for the first time in Milan by Italian biologist Giuseppe Simoni, scientific director of Biocell Center, in 1983.[4] Use as early as eight weeks in special circumstances has been described.[5] It can be performed in a transcervical or transabdominal manner.[2] Although this procedure is mostly associated with testing for Down syndrome, overall, CVS can detect more than 200 disorders.[6]

Indications

Possible reasons for having a CVS can include:

- Abnormal first trimester screen results

- Increased nuchal translucency or other abnormal ultrasound findings

- Family history of a chromosomal abnormality or other genetic disorder

- Parents are known carriers for a genetic disorder

- Advanced maternal age (maternal age above 35). AMA is associated with increase risk of Down's syndrome and at age 35, risk is 1:400. Screening tests are usually carried out first before deciding if CVS should be done.

Risks

The risk of miscarriage in CVS is estimated to be potentially as high as 1-2%. However some recent research has suggested that only a very small number of miscarriages that occur after CVS are a direct result of the procedure.[7] Apart from a risk of miscarriage, there is a risk of infection and amniotic fluid leakage. The resulting amniotic fluid leak can develop into a condition known as oligohydramnios, which is low amniotic fluid level. If the resulting oligohydramnios is not treated and the amniotic fluid continues to leak it can result in the baby developing hypoplastic lungs (underdeveloped lungs).[8][9]

Additionally, there is also mild risk of Limb Reduction Defects associated with CVS, with the risk being higher the earlier the procedure is carried.[10]

It is important after having CVS that the obstetrician follows the patient closely to ensure the patient does not develop infection.

Chorionic villi and stem cells

Recent studies have discovered that chorionic villi can be a rich source of fetal stem cells, multipotent mesenchymal stem cells[11][12][13]

A potential benefit of using fetal stem cells over those obtained from embryos is that they side-step ethical concerns among anti-abortion activists by obtaining pluripotent lines of undifferentiated cells without harm to a fetus or destruction of an embryo. These stem cells would also, if used to treat the same individual they came from, sidestep the donor/recipient issue which has so far stymied all attempts to use donor-derived stem cells in therapies.

Artificial heart valves, working tracheas, as well as muscle, fat, bone, heart, neural and liver cells have all been engineered through use of fetal stem cells[14]

The first fetal stem cells bank in US is active in Boston, Massachusetts.[15][16][17][18]

Limitations

A small percentage (1-2%) of pregnancies have confined placental mosaicism, where some but not all of the placental cells tested in the CVS are abnormal, even though the pregnancy is unaffected.[19] Cells from the mother can be mixed with the placental cells obtained from the CVS procedure. Occasionally if these maternal cells are not completely separated from the placental sample, this can lead to discrepancies with the results. This phenomenon is called Maternal Cell Contamination (MCC).[19] CVS cannot detect all birth defects. It is used for testing chromosomal abnormalities or other specific genetic disorders only if there is family history or other reason to test.

See also

- Amniocentesis

- Cell-free fetal DNA

- Elective genetic and genomic testing

- Percutaneous umbilical cord blood sampling

- Prenatal testing

References

- A PubMed search yields 168 papers using chorionic villous as of June 15, 2011.

- Alfirevic, Z.; Sundberg, K.; Brigham, S. (2003). Alfirevic, Zarko (ed.). "Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD003252. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003252. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4171981. PMID 12917956.

- Alfirevic, Z. (2000). "Early amniocentesis versus transabdominal chorion villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000077. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000077. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 10796116. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000077)

- Brambati, B.; Simoni, G. (1983). "Diagnosis of fetal trisomy 21 in first trimester". The Lancet. 1 (8324): 586. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92831-3. PMID 6131275. S2CID 42553451.

- Wapner, Ronald J.; Evans, Mark I.; Davis, George; Weinblatt, Vivian; Moyer, Sue; Krivchenia, Eric L.; Jackson, Laird G. (2002). "Procedural risks versus theology: Chorionic villus sampling for Orthodox Jews at less than 8 weeks' gestation". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 186 (6): 1133–6. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.122983. PMID 12066086.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Chorionic villus sampling

- "Chorionic villus sampling - Risks". NHS Choices. Retrieved 2016-05-24. Page last reviewed: 06/08/2015

- Wu, Chun-Shan; Chen, Chung-Ming; Chou, Hsiu-Chu (February 2017). "Pulmonary Hypoplasia Induced by Oligohydramnios: Findings from Animal Models and a Population-Based Study". Pediatrics and Neonatology. 58 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.04.001. ISSN 2212-1692. PMID 27324123.

- Spong, C. Y. (December 2001). "Preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes complicated by oligohydramnios". Clinics in Perinatology. 28 (4): 753–759, vi. doi:10.1016/s0095-5108(03)00075-7. ISSN 0095-5108. PMID 11817187.

- "Chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis: recommendations for prenatal counseling. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". MMWR. 44 (RR-9): 1–12. 1995. PMID 7565548.

- Weiss, Rick (2007-01-08). "Scientists See Potential In Amniotic Stem Cells". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- De Coppi, Paolo; Bartsch, Georg; Siddiqui, M Minhaj; Xu, Tao; Santos, Cesar C; Perin, Laura; Mostoslavsky, Gustavo; Serre, Angéline C; Snyder, Evan Y; Yoo, James J; Furth, Mark E; Soker, Shay; Atala, Anthony (2007). "Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy". Nature Biotechnology. 25 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1038/nbt1274. PMID 17206138. S2CID 6676167.

- "Stem Cells – BiocellCenter". Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Stem cells scientific updates – BiocellCenter". Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "European Biotech Company Biocell Center Opens First U.S. Facility for Preservation of Amniotic Stem Cells in Medford, Massachusetts". Reuters. 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Europe's Biocell Center opens Medford office – Daily Business Update – The Boston Globe". 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "The Ticker - BostonHerald.com". Archived from the original on 2012-09-21. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- "Biocell partner with largest New England's hospital group to preserve amniotic stem cell". Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- Wapner, Ronald J. (2005). "Invasive Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques". Seminars in Perinatology. 29 (6): 401–4. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.003. PMID 16533654.

External links

- Chorionic Villus Sampling - March of Dimes

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: 003406

- Cleveland Clinic

- CVS Test: Six Months of Worry Free Pregnancy

- Chorionic Villus Sampling - slideshow by The New York Times