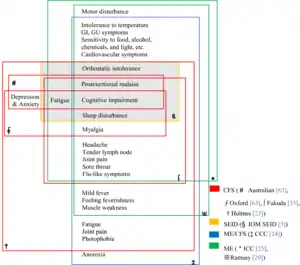

Clinical descriptions of chronic fatigue syndrome

Clinical descriptions of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) vary. Different groups have produced sets of diagnostic criteria that share many similarities. The biggest differences between criteria are whether post-exertional malaise (PEM) is required, and the number of symptoms needed.[1] Aspects of the condition are controversial, with disagreements over etiology, pathophysiology, treatment and naming between medical practitioners, researchers, patients and advocacy groups. Furthermore, diagnosing CFS can be difficult due to several factors, including lack of a standard test and non-specific symptoms.[1] Subgroup analysis suggests that, depending on the applied definition, CFS may represent a variety of conditions rather than a single disease entity.[2][3]

Definitions

2015 IOM criteria

The IOM criteria come from the IOM's 2015 report on CFS, and the CDC currently uses this definition.[4] The IOM criteria require the following three symptoms:

- Severe, disabling fatigue of new onset

- Post-exertional malaise (PEM)

- Unrefreshing sleep.

Also, at least one of the following is required:

- Cognitive impairment

- Orthostatic intolerance

They also note that for all symptoms except orthostatic intolerance, "frequency and severity of symptoms should be assessed," and that these symptoms should be present at least half the time with at least moderate severity.[5]

CDC 1994 criteria

The most widely used diagnostic criteria for CFS[6] are the 1994 research guidelines proposed by the "International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group", led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[7][8] These criteria are sometimes called the "Fukuda definition" after the first author (Keiji Fukuda) of the publication. The 1994 CDC criteria specify the following conditions must be met:

- Primary symptoms

Clinically evaluated, unexplained, persistent or relapsing chronic fatigue that is:

- of new or definite onset (has not been lifelong);

- is not the result of ongoing exertion;

- is not substantially alleviated by rest; and

- results in substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities.

- Additional requirements

The concurrent occurrence of four or more of the following symptoms, all of which must have persisted or recurred during six or more consecutive months of illness and must not have predated the fatigue:

- self-reported impairment in short-term memory or concentration severe enough to cause substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities;

- sore throat;

- tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes;

- muscle pain;

- multi-joint pain without joint swelling or redness;

- headaches of a new type, pattern, or severity;

- unrefreshing sleep;

- post-exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours.

- Final requirement

All other known causes of chronic fatigue must have been ruled out, specifically clinical depression, side effects of medication, eating disorders and substance abuse.

The clinical evaluation should include:

- A thorough history that covers medical and psychosocial circumstances at the onset of fatigue; depression or other psychiatric disorders; episodes of medically unexplained symptoms; alcohol or other substance abuse; and current use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and food supplements;

- A mental status examination to identify abnormalities in mood, intellectual function, memory, and personality. Particular attention should be directed toward current symptoms of depression or anxiety, self-destructive thoughts, and observable signs such as psychomotor retardation. Evidence of a psychiatric or neurologic disorder requires that an appropriate psychiatric, psychological, or neurologic evaluation be done;

- A thorough physical examination;

- A minimum battery of laboratory screening tests, including complete blood count with leukocyte differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, calcium, phosphorus, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, electrolytes, and creatinine; determination of thyroid-stimulating hormone; and urinalysis.

Other diagnostic tests have no recognized value unless indicated on an individual basis to confirm or exclude a differential diagnosis, such as multiple sclerosis.

CDC 1988 criteria

The initial chronic fatigue syndrome definition was published in 1988. It is also called the "Holmes definition", after the manuscript's first author.[9]

The Homes criteria require these two points:

- Debilitating fatigue of new onset which interferes with the patient's daily activities

- Other fatiguing conditions must be eliminated

They define 11 symptom criteria:

- Mild fever or chills

- Sore throat

- Sore lymph nodes

- Muscle weakness

- Muscle discomfort or myalgia

- Fatigue after exercise lasting at least 24 hours

- Headaches

- Joint pain

- Hypersomnia or insomnia

- A rapid onset over a few hours or days

And three physical criteria that must be documented by a physician:

- Low-grade fever

- Nonexudative pharyngitis

- Tender lymph nodes

To make a diagnosis, a patient must meet either 8 of the 11 symptom criteria, or 6 of the 11 symptom criteria and 2 of 3 physical criteria.[9]

Oxford 1991 criteria

The Oxford criteria were published in 1991[10] and include both CFS of unknown etiology and a subtype of CFS called post-infectious fatigue syndrome (PIFS), which "either follows an infection or is associated with a current infection." The Oxford criteria defines CFS as follows:

- Fatigue must be the main symptom

- There must be a definite onset

- The fatigue must be debilitating

- The fatigue must have lasted for 6 months or longer, and be present at least 50% of the time

- Other symptoms are possible, such as muscle pain, mood problems, or sleep disturbance

- Conditions known to cause severe fatigue and some mental conditions exclude a diagnosis.

Post-infectious fatigue syndrome also requires evidence of a prior infection.[10]

The Oxford criteria differ from the Fukuda criteria in that mental fatigue is required and that symptoms that could be psychiatric in origin can count toward a diagnosis. Likewise, the Oxford criteria differs from the Canadian consensus criteria by not excluding patients who may have a psychiatric condition.[6]

Canadian consensus criteria

The Canadian consensus criteria were initiated by Health Canada and published by an international group of researchers in 2003.[11] The requirements are summarized as follows:

- Severe fatigue

- "Post-Exertional Malaise and/or Fatigue"

- Sleep dysfunction

- Myalgia

- Two or more neurological or cognitive symptoms

- At least one symptom from the lists for two of these categories:

- Autonomic symptoms

- Neuroendocrine symptoms

- Immune symptoms

- Symptoms must be present for at least 6 months[11]

Unlike some criteria, the Canadian consensus criteria exclude patients with symptoms of mental illness.[6] This definition was updated in 2010 to provide greater specification to the original. Functional impairment must be below defined thresholds in two of the three designated subscales of the Short Form 36 Health Survey i.e. Vitality, Social Functioning, and Role-Physical.

London criteria

The London Criteria were designed for research purposes and used by Action for ME in all studies they funded until the mid-1990s. An incomplete version edited by Nick Anderson (CEO of AFME) was published in a 1994 report. The London criteria require the following:

- Fatigue triggered by exercise

- Impaired short-term memory and concentration

- Fluctuating symptoms, usually in response to exertion

These symptoms must have lasted at least 6 months. The London criteria also mention that other symptoms, including autonomic and immune symptoms, are common and may help confirm a diagnosis.[12] In light of the advances in understanding of ME and CFS, the criteria for ME as described by Ramsay and others were updated in 2009.[13] These have been cited in articles and are being evaluated as of 2011, for example, in studies to ascertain differences between patients selected using different case definitions.[14]

International Consensus Criteria

The International Consensus Criteria were based on the Canadian consensus criteria and developed by a group of 26 individuals from 13 countries and consisting of clinicians, researchers, teaching faculty, and an independent patient advocate. The ICC define the illness as:

- "Postexertional neuroimmune exhaustion" or PENE

- Neurological symptoms: patients must have at least one symptom from one of the four lists:

- Neurocognitive impairments

- Pain

- Sleep distubrance

- "Neurosensory, perceptual and motor disturbances"

- Immune, gastrointestinal and genitourinary symptoms: patients must have at least one symptom in three of five areas:

- Flu-like symptoms

- Gets sick from viruses easily

- Gastro-intestinal symptoms

- Genitourinary symptoms

- Sensitivity to food, medicines, or chemicals

- Energy production symptom: patients must have at least one symptom from any of the four lists

- Cardiovascular symptoms

- Respiratory symptoms

- Temperature dysregulation

- Intolerance of heat or cold

The ICC definition also notes that children may have somewhat different symptoms, and that symptoms tend to be more variable.[15]

Compared to the Canadian criteria, chronic fatigue is not required, and there is no requirement for symptoms to occur for 6 months. The main symptom is "post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion" (PENE), which encompasses fatigability, symptoms worsening after exertion, exhaustion after exertion, a prolonged recovery from activity, and reduction of activities due to symptoms. The ICC definition describes severity levels: Mild ME is described as roughly a 50% in functioning compared to before the illness, moderate ME makes one mostly housebound, severe refers to mostly bed-bound, and a very severe being completely bed-bound and requiring care from others.[15]

National guidelines

Several countries, including Australia[16] and the United Kingdom, have authored clinical guidelines that define CFS based on some or all of the available diagnostic criteria. The 2021 UK NICE guideline requires all of the following symptoms:

- Debilitating fatigue

- Post-exertional malaise

- Unrefreshing and/or disturbed sleep

- Cognitive difficulties

Additionally, the symptoms must be present for at least 6 weeks in adults and 4 weeks in children, and not explained by another condition.[17]

Testing

As there is no generally accepted test for chronic fatigue syndrome, diagnosis is based on symptoms, history, and ruling out other conditions.[18]

The CDC states that diagnostic tests should be directed to confirm or exclude other causes for fatigue and other symptoms. Further tests may be individually necessary to identify underlying or contributing conditions that require treatment. The use of testing as evidence for the diagnosis chronic fatigue syndrome should only be done in the context of protocol-based research. The following routine tests are recommended:[8][18]

- Complete blood count

- Blood chemistry (electrolytes, glucose, renal function, liver enzymes, and protein levels).

- Thyroid function tests

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-Reactive protein

- Iron tests

- Celiac disease screening

- Urinalysis for blood cells, protein and glucose

In addition to the CDC's recommendation, the NICE guideline recommends HbA1c and creatine kinase tests, and mentions that blood tests for vitamins D and B12, infectious diseases, and adrenal insufficiency may be warranted.[17] The old 2007 NICE guideline discourages routine performance of the head-up tilt test, auditory brainstem response and electrodermal conductivity for the purpose of diagnosis.[19]: 37

Diagnostic complications and suggested improvements

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England and Wales states that none of the existing case definitions are based on robust evidence, and no studies have confirmed any case definition to be superior to others.[19]: 144

Some researchers say that subtypes of CFS may exist.[2][3]

CDC 1994

A 2003 international CFS study group for the CDC found ambiguities in the CDC 1994 CFS research case definition which contribute to inconsistent case identification.[20] Different self-reported causes of CFS are associated with significant differences in clinical measures and outcomes.[21]

An examination of the CDC 1994 criteria applied to several hundred patients found that the diagnosis could be strengthened by adding two new symptoms (anorexia and nausea) and eliminating three others (muscle weakness, joint pain, sleep disturbance).[22] Other suggested improvements to the diagnostic criteria include the use of severity ratings.[23]

CDC Empirical definition 2005

A new "empirical definition" of the CDC 1994 criteria was published in 2005.[24] A 2009 evaluation of the 2005 empirical definition compared 27 patients with a prior diagnosis of CFS with 37 patients diagnosed with a Major Depressive Disorder. The researchers reported that "38% of those with a diagnosis of a Major Depressive Disorder were misclassified as having CFS using the new CDC definition."[25]

References

- "Understanding History of Case Definitions and Criteria | Healthcare Providers | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- Jason LA, Corradi K, Torres-Harding S, Taylor RR, King C (March 2005). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: the need for subtypes". Neuropsychol Rev. 15 (1): 29–58. doi:10.1007/s11065-005-3588-2. PMID 15929497. S2CID 8153255.

- Jason LA, Taylor RR, Kennedy CL, Song S, Johnson D, Torres S (September 2000). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: occupation, medical utilization, and subtypes in a community-based sample". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 188 (9): 568–76. doi:10.1097/00005053-200009000-00002. PMID 11009329.

- "IOM 2015 Diagnostic Criteria | Diagnosis | Healthcare Providers | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness (PDF). National Academy of Medicine. 2015. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-309-31689-7.

- Wyller VB (2007). "The chronic fatigue syndrome – an update". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 187: 7–14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00840.x. PMID 17419822. S2CID 11247547.

- "About CFS: What is Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- Fukuda K, Straus S, Hickie I, Sharpe M, Dobbins J, Komaroff A (15 December 1994). "The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group". Ann Intern Med. 121 (12): 953–59. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. PMID 7978722. S2CID 510735.

- Holmes GP; Kaplan JE; Gantz NM; et al. (March 1988). "Chronic fatigue syndrome: a working case definition". Ann. Intern. Med. 108 (3): 387–89. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-387. PMID 2829679. S2CID 42395288. Details Archived 29 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Sharpe MC; Archard LC; Banatvala JE; et al. (February 1991). "A report--chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research". J R Soc Med. 84 (2): 118–21. doi:10.1177/014107689108400224. PMC 1293107. PMID 1999813. Synopsis by "Oxford criteria for the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syn". GPnotebook.)

- Carruthers BM; et al. (2003). "Myalgic encephalomyalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols" (PDF). Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 11 (1): 7–36. doi:10.1300/J092v11n01_02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2008.

- Shepherd, Charles (21 February 2011). "London Criteria for M.E. – for website discussion". The ME Association. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- Howes, S; Goudsmit, E; Shepard, C. "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). Criteria and clinical guidelines 2014". Axford's Abode. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- Jason, LA; Brown AA; Clyne E; Bartgis L; Evans M; Brown M. (December 2011). "Contrasting case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis". Evaluation & the Health Professions. 35 (3): 280–304. doi:10.1177/0163278711424281. PMC 3658447. PMID 22158691.

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, Staines D, Powles AC, Speight N, Vallings R, Bateman L, Baumgarten-Austrheim B, Bell DS, Carlo-Stella N, Chia J, Darragh A, Jo D, Lewis D, Light AR, Marshall-Gradisbik S, Mena I, Mikovits JA, Miwa K, Murovska M, Pall ML, Stevens S (October 2011). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria". J Intern Med. 270 (4): 327–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. PMC 3427890. PMID 21777306.

- Australian Guidelines (2002)

- "Recommendations | Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- "Diagnosis of ME/CFS". Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. 27 January 2021.

- Turnbull N, Shaw EJ, Baker R, Dunsdon S, Costin N, Britton G, Kuntze S, Norman R (August 2007). "Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy):diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy) in adults and children". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Reeves WC; Lloyd A; Vernon SD; et al. (December 2003). "Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution". BMC Health Serv Res. 3 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-3-25. PMC 317472. PMID 14702202.

- Kennedy G, Abbot NC, Spence V, Underwood C, Belch JJ (February 2004). "The specificity of the CDC-1994 criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome: comparison of health status in three groups of patients who fulfill the criteria". Ann Epidemiol. 14 (2): 95–100. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.10.004. PMID 15018881.

- Komaroff AL; Fagioli LR; Geiger AM; et al. (January 1996). "An examination of the working case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome". Am. J. Med. 100 (1): 56–64. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(96)90012-1. PMID 8579088.

- King C, Jason LA (February 2005). "Improving the diagnostic criteria and procedures for chronic fatigue syndrome". Biol Psychol. 68 (2): 87–106. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.595.4767. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.015. PMID 15450690. S2CID 12601890.

- Reeves, William; Dieter Wagner; Rosane Nisenbaum; James Jones; Brian Gurbaxani; Laura Solomon; Dimitris Papanicolaou; Elizabeth Unger; Suzanne Vernon; Christine Heim (2005). "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – A clinically empirical approach to its definition and study". BMC Medicine. 3: 19. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-3-19. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 1334212. PMID 16356178.

- Jason, Leonard A; Najar, Natasha; Porter, Nicole; Reh, Christy (2009). "Evaluating the Centers for Disease Control's Empirical Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Case Definition". Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 20 (2): 93–100. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.508.1082. doi:10.1177/1044207308325995. S2CID 71852821.