dextro-Transposition of the great arteries

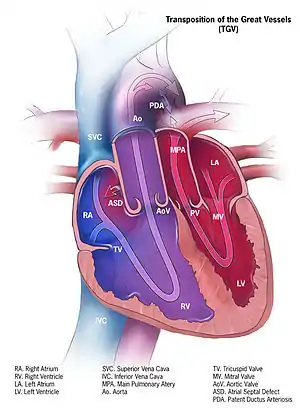

dextro-Transposition of the great arteries (d-Transposition of the great arteries, dextro-TGA, or d-TGA) is a potentially life-threatening birth defect in the large arteries of the heart.[1] The primary arteries (the aorta and the pulmonary artery) are transposed.[1]

| Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Complete transposition of the great arteries |

| |

| Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

It is called a cyanotic congenital heart defect (CHD) because the newborn infant turns blue from lack of oxygen. In segmental analysis, this condition is described as ventriculoarterial discordance with atrioventricular concordance, or just ventriculoarterial discordance. d-TGA is often referred to simply as transposition of the great arteries (TGA); however, TGA is a more general term which may also refer to levo-transposition of the great arteries (l-TGA).Another term commonly used to refer to both d-TGA and l-TGA is transposition of the great vessels (TGV), although this term might have an even broader meaning than TGA.

Prenatally, a baby with d-TGA experiences no symptoms as the lungs will not be used until after birth, and oxygen is provided by the mother via the placenta and umbilical cord; in order for the red blood to bypass the lungs in utero, the fetal heart has two shunts that begin to close when the newborn starts breathing; these are the foramen ovale and the ductus arteriosus. The foramen ovale is a hole in the atrial septum which allows blood from the right atrium to flow into the left atrium; after birth, the left atrium will be filled with blood returning from the lungs and the foramen ovale will close. The ductus arteriosus is a small, artery-like structure which allows blood to flow from the trunk of the pulmonary artery into the aorta; after birth, the blood in the pulmonary artery will flow into the lungs and the ductus arteriosus will close. Sometimes these shunts will fail to close after birth; these defects are called patent foramen ovale and patent ductus arteriosus, and either may occur independently, or in combination with one another, or with d-TGA or other heart and/or general defects.

Symptoms and signs

Due to the low oxygen saturation of the blood, cyanosis will appear in peripheral areas: around the mouth and lips, fingertips, and toes; these areas are furthest from the heart, and since the circulated blood is not fully oxygenated to begin with, very little oxygen reaches the peripheral arteries.[2] A d-TGA baby will exhibit indrawing beneath the ribcage and "comfortable tachypnea" (rapid breathing); this is likely a homeostatic reflex of the autonomic nervous system in response to hypoxic hypoxia.[3] The infant will be easily fatigued and may experience weakness, particularly during feeding or playing; this interruption to feeding combined with hypoxia can cause failure to thrive.[2] If d-TGA is not diagnosed and corrected early on, the infant may eventually experience syncopic episodes and develop clubbing of the fingers and toes.

Diagnosis

d-TGA can sometimes be diagnosed in utero with an ultrasound after 18 weeks gestation.[2] However, if it is not diagnosed in utero, cyanosis of the newborn (blue baby) should immediately indicate that there is a problem with the cardiovascular system. Normally, the lungs are examined first, then the heart is examined if there are no apparent problems with the lungs. These examinations are typically performed using ultrasound, known as an echocardiogram when performed on the heart.[2][3] Chest x-rays and electrocardiograms may also be used in reaching or confirming a diagnosis; however, an x-ray may appear normal immediately following birth.[2][3] If d-TGA is accompanied by both a VSD and pulmonary stenosis, a systolic murmur will be present.

On the rare occasion (when there is a large VSD with no significant left ventricular outflow tract obstruction), initial symptoms may go unnoticed, resulting in the infant being discharged without treatment in the event of a hospital or birthing center birth, or a delay in bringing the infant for diagnosis in the event of a home birth. On these occasions, a layperson is likely not to recognize symptoms until the infant is experiencing moderate to serious congestive heart failure (CHF) as a result of the heart working harder in a futile attempt to increase oxygen flow to the body; this overworking of the heart muscle eventually leads to hypertrophy and may result in cardiac arrest if left untreated.

Description

In a normal heart, oxygen-depleted ("blue") blood is pumped from the right side of the heart, through the pulmonary artery, to the lungs where it is oxygenated. The oxygen-rich ("red") blood then returns to the left heart, via the pulmonary veins, and is pumped through the aorta to the rest of the body, including the heart muscle itself.

With d-TGA, deoxygenated blood from the right heart is pumped immediately through the aorta and circulated to the body and the heart itself, bypassing the lungs altogether, while the left heart pumps oxygenated blood continuously back into the lungs through the pulmonary artery. In effect, two separate "circular" (parallel) circulatory systems are created, rather than the "figure 8" (in series) circulation of a normal cardio-pulmonary system.

Arterial spatial relationships

Differences in the shape of the atrial septum and/or ventricular outflow tracts affect the relative positions of the aorta and pulmonary artery. In the majority of d-TGA cases, the aorta is anterior and to the right of the pulmonary artery, but it can also be directly anterior or anterior and to the left. The aorta and pulmonary artery can also be side by side, with aorta on either side. This is a less common variant, and with this arrangement, an unusual coronary artery pattern is common. There are also some cases with aorta to the right and posterior to the pulmonary artery.[4]

Simple and complex d-TGA

d-TGA is often accompanied by other heart defects, the most common type being intracardiac shunts such as atrial septal defect (ASD) including patent foramen ovale (PFO), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Stenosis of valves or vessels may also be present.

When no other heart defects are present it is called 'simple' d-TGA; when other defects are present it is called 'complex' d-TGA.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, complex d-TGA presents better chance of survival and less developmental risks than simple d-TGA, as well as usually requiring fewer invasive palliative procedures. This is because the left-to-right and bidirectional shunting caused by the defects common to complex d-TGA allow a higher amount of oxygen-rich blood to enter the systemic circulation. However, complex d-TGA may cause a very slight increase to length and risk of the corrective surgery, as most or all other heart defects will normally be repaired at the same time, and the heart becomes "irritated" the more it is manipulated.[5]

Treatment

Life-saving heart surgery is always required.[2][3] If the diagnosis is made in a standard hospital or other clinical facility, the baby will be transferred to a children's hospital, if such facilities are available, for specialized paediatric treatment and equipment.

The patient will require constant monitoring and care in an intensive care unit (ICU).

Palliative

Palliative treatment is normally administered prior to corrective surgery in order to reduce the symptoms of d-TGA (and any other complications), giving the newborn or infant a better chance of surviving the surgery. Treatment may include any combination of:

Minor

Cardiac catheterization is a minimally invasive procedure which provides a means of performing a number of other procedures.[3]

A balloon atrial septostomy is performed with a balloon catheter, which is inserted into a patent foramen ovale (PFO), or atrial septal defect (ASD) and inflated to enlarge the opening in the atrial septum; this creates a shunt which allows a larger amount of oxygenated ("red") blood to enter the systemic circulation.

Angioplasty also requires a balloon catheter, which is used to stretch open a stenotic vessel; this relieves restricted blood flow, which could otherwise lead to congestive heart failure (CHF).

An endovascular stent is sometimes placed in a stenotic vessel immediately following a balloon angioplasty to maintain the widened passage.

Angiography involves using the catheter to release a contrast medium into the chambers and/or vessels of the heart; this process facilitates examining the flow of blood through the chambers during an echocardiogram, or shows the vessels clearly on a chest x-ray, MRI, or CT scan - this is of particular importance, as the coronary arteries must be carefully examined and "mapped out" prior to the corrective surgery.

It is commonplace for any of these palliations to be performed on a d-TGA patient.

Moderate

- Left anterior thoracotomy

- Isolated pulmonary artery banding (PAB)

- Left lateral thoracotomy

- PAB (when coarctation or aortic arch repair also required)

- Right lateral thoracotomy

- Blalock-Hanlon atrial septectomy

Each of these procedures is performed through an incision between the ribs and visualized by echocardiogram; these are far less common than heart cath procedures.

Pulmonary artery banding is used in a small number of cases of d-TGA, usually when the corrective surgery needs to be delayed, to create an artificial stenosis in order to control pulmonary blood pressure; PAB involves placing a band around the pulmonary trunk, this band can then be quickly and easily adjusted when necessary.

An atrial septectomy is the surgical removal of the atrial septum; this is performed when a patent foramen ovale (PFO), or atrial septal defect (ASD) are not present and additional shunting is required to raise the oxygen saturation of the blood flowing eventually into the aorta.

Major

- Median sternotomy

- PAB (when intracardiac procedures also required)

- Concomitant atrial septectomy

In recent years, it is quite rare for palliative procedures to be done via median sternotomy. However, if a sternotomy is required for a different procedure, in most cases all procedures that are immediately required will be performed at the same time.

Monitoring and maintenance

- Nasogastric tube (NG tube or simply NG)

- Intubation, oxygen mask, or nasal cannula

- Intravenous drip (IV)

- Arterial line

- Central venous catheter

- Fingerprick

- Sphygmomanometer

- Pulse oximeter

- EKG

An NG tube is used to deliver nourishment, and occasionally medication, to the patient. Since the tube extends right into the stomach, it can also be used to monitor how well the patient is digesting their "food". Paediatric units normally provide facilities and equipment for mothers of infant patients to pump their breastmilk, which can then be fed to the infant through the NG tube, and/or stored for later use.

Oxygen therapy is commonplace for hospitalized d-TGA patients. This may range from an oxygen mask resting on the bed nearby their head to intubation. In some cases, patients are intubated as a precaution; the machine can monitor breathing and supplement the patient as much or as little as they need.

IV's are used to deliver medication, blood products, or other fluids to the patient. Arterial lines provide a constant monitor of blood pressure, as well as a method of obtaining samples for blood gas tests; central lines can also monitor blood pressure and provide blood samples, as well as provide a means to deliver medication and nourishment; fingerpricks (or heelpricks on small babies) are used to obtain blood samples for certain tests.

A sphygmomanometer may be used for intermittent blood pressure monitoring even if a patient is being otherwise monitored using a central or arterial line.

A pulse oximeter is attached to a finger or toe and provides constant or intermittent monitoring of the blood's oxygen saturation level.[2]

An EKG creates a visual readout of how well the heart rhythm is functioning.[2]

Medication

When PGE is administered to a newborn, it prevents the ductus arteriosus from closing, therefore providing an additional shunt through which to provide the systemic circulation with a higher level of oxygen.[3]

Antibiotics may be administered preventatively. However, due to the physical strain caused by uncorrected d-TGA, as well as the potential for introduction of bacteria via arterial and central lines, infection is not uncommon in pre-operative patients.

Diuretics aid in flushing excess fluid from the body, thereby easing strain on the heart.

Analgesics normally are not used pre-operatively, but they may be used in certain cases. They are occasionally used partially for their sedative effects.

Cardiac glycosides are used to maintain proper heart rhythm while increasing the strength of each contraction.

Sedatives may be used palliatively to prevent a young child from thrashing about or pulling out any of their lines.

Nikaidoh

Bex who introduced the possibility of aortic translocation in 1980. But Nikaidoh has put the procedure in practice in 1984. It results in an anatomical normal heart, even better than with an ASO, because also the cones are switched instead of only the arteries as with an ASO. The procedure is contra-indicated by certain coronary anomalies.

In 1984, Nikaidoh introduced a surgical approach for the management of TGA, VSD, and pulmonary stenosis (PS), which he called "aortic translocation and biventricular outflow tract reconstruction". The repair consisted of harvesting the aortic root from the right ventricle, with or without the coronary arteries attached, and relieving the LVOTO by dividing the outlet septum and pulmonary valve annulus. The LVOT is then restored by posteriorly translocating the aortic root and closing the VSD. Finally, the right ventricular outflow tract is reconstructed with a pericardial patch. This is a technically challenging procedure, but results in a more "normal" anatomic repair. The main thing is the repositioning of the native aortic root over to the LV cavity, avoiding the creation of a long tortuous intraventricular tunnel. This technique appears to prevent the development of LVOTO, which is a frequent complication of the Rastelli repair. The addition of the Lecompte maneuver may prevent branch pulmonary artery stenosis that may occur secondary to compression of the PA by the posteriorly displaced, translocated aortic root. It creates a direct RV to PA anastomosis and avoiding the use of a conduit, which should decrease the incidence of RVOT reinterventions.

Lecompte

Since 1981 LeCompte has put his LeCompte manoeuvre in use. This is used with the REV (Réparation à l'Etage Ventriculaire). This surgery is like the Rastelli procedure, but with the use of the pulmonary artery without a conduit.

Rastelli

When an arterials switch operation (ASO) is not possible e.g. in case of LVOTO an option is the Rastelli procedure. The pulmonal artery is shifted with help of conduit to the right ventricle. It has been used since 1960s. It has a disadvantage that the conduit does not grow, so re-operation is necessary.

Arterial switch

The Jatene procedure surgery is the preferred, and most frequently used, method of correcting d-TGA.[2][6] It is ideally performed on an infant between 8–14 days old.

The heart and vessels are accessed via median sternotomy, and a cardiopulmonary bypass machine is used; as this machine needs its "circulation" to be filled with blood, a child will require a blood transfusion for this surgery. The procedure involves transecting both the aorta and pulmonary artery; the coronary arteries are then detached from the aorta and reattached to the neo-aorta, before "swapping" the upper portion of the aorta and pulmonary artery to the opposite arterial root. Including the anaesthesia and immediate post operative recovery, this surgery takes an average of approximately six to eight hours to complete.

Some arterial switch recipients may present with post-operative pulmonary stenosis, which would then be repaired with angioplasty, pulmonary stenting via heart cath or median sternotomy, and/or xenograft.

Atrial switch

In some cases, it is not possible to perform an arterial switch, either because of late diagnosis, sepsis, or a contraindicative coronary artery pattern. In the case of sepsis or late diagnosis, a delayed Arterial Switch can sometimes be made possible by PAB, which may also require a concomitant construction of an aortic-to-pulmonary artery shunt.[2]

When an arterial switch is impossible, an atrial switch will be attempted using either the Senning or Mustard procedure.[7] Both methods involve creating a baffle to redirect red and blue blood flow to the appropriate artery. Since the late 1970s the Mustard procedure has been preferred.

Post-operative

Following corrective surgery, but prior to cessation of anaesthesia, two small incisions are made immediately below the sternotomy incision which provide exit points for chest tubes used to drain fluid from the thoracic cavity, with one tube placed at the front and another at the rear of the heart.

The patient returns to the ICU post-operatively for recovery, maintenance, and close observation; recovery time may vary, but tends to average approximately two weeks, after which the patient may be transferred to a Transitional Care Unit (TCU), and eventually to a cardiac ward.

Post-operative care is very similar to the palliative care received, with the exception that the patient no longer requires PGE or the surgical palliation procedures. Additionally, the patient is kept on a cooling blanket for a period of time to prevent fever, which could cause brain damage. The sternum is not closed immediately which allows extra space in the thoracic cavity, preventing excess pressure on the heart, which swells considerably following the surgery; the sternum and incision are closed after a few days, when swelling is sufficiently reduced.

Follow-up

The infant will continue to see a cardiologist on a regular basis.[2] Although these appointments are required less frequently as time goes on, they will continue throughout the lifetime of the individual, and may increase in the event of complications or as the individual approaches middle age.

The cardiology exam may include an echocardiogram, EKG, and/or cardiac stress test in addition to consultation.

Additionally, some individuals may require ongoing medication therapy at home, which may include diuretics (such as furosemide or spironolactone), analgesics (such as paracetamol), cardiac glycosides (such as digoxin), anticoagulants (such as heparin or aspirin), or other medications. If the individual has undergone stenting, an anticoagulant will be a necessity to prevent build-up around the stent(s), as the body will perceive the foreign body as a wound and attempt to heal it.

Some patients who had alternate corrective surgery, such as the Mustard or Senning procedure, may have issues with SA and VA nodal transmissions in later life. Typical symptoms include palpitations and problems with low heart rates. This is commonly solved with a Pacemaker unit, providing scar tissue from the original operation does not block its functionality.

More recently, ACE inhibitors have been prescribed to patients in the hope of relieving stress on the heart.

Prognosis

With simple d-TGA, if the foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus are allowed to close naturally, the newborn will likely not survive long enough to receive corrective surgery. With complex d-TGA, the infant will fail to thrive and is unlikely to survive longer than a year if corrective surgery is not performed. In most cases, the patient's condition will deteriorate to the point of inoperability if the defect is not corrected in the first year.

While the foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus are open after birth, some mixing of red and blue blood occurs allowing a small amount of oxygen to be delivered to the body; if ASD, VSD, PFO, and/or PDA are present, this will allow a higher amount of the red and blue blood to be mixed, therefore delivering more oxygen to the body, but can complicate and lengthen the corrective surgery and/or be symptomatic.

Modern repair procedures within the ideal timeframe and without additional complications have a very high success rate.[2]

Epidemiology

Heart defects are the most common birth defect, occurring in approximately 1% of live births. 5–7% of these are dextro-transposition of the great arteries.[7] Such defects appear to be more common in men than women.[8] Approximately one million people worldwide are currently living with a CHD.Having a child with a CHD increases an individual's chances of having another child with a CHD from 1% to 3%. Subsequent children born with a CHD increase that individual's chances further.

References

- Tsai, Kevin Luke; Al'Aref, Subhi J.; van Rosendael, Alexander R.; Bax, Jeroen J. (2018-01-01), Al'Aref, Subhi J.; Mosadegh, Bobak; Dunham, Simon; Min, James K. (eds.), "Chapter 5 - Complex Congenital Heart Disease", 3D Printing Applications in Cardiovascular Medicine, Boston: Academic Press, pp. 79–101, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803917-5.00005-5, ISBN 978-0-12-803917-5, retrieved 2020-11-11

- CDC (2019-11-22). "Congenital Heart Defects - dextro-Transposition of the Great Arteries". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- "default - Stanford Children's Health". www.stanfordchildrens.org. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Valdes-Cruz LM and Cayre RO: Chapter 24 in Echocardiographic diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Philadelphia 1998.

- Semrád, Michal (2014). Cardiovascular surgery. Milan Krajíček, Timoteus Pokora. Prague. ISBN 978-80-246-2599-7. OCLC 909908858.

- Wong, Tom; Janousek, Jan; Lim, Eric (2018-01-01), Gatzoulis, Michael A.; Webb, Gary D.; Daubeney, Piers E. F. (eds.), "19 - Pacemakers and Internal Cardioverter Defibrillators in Adult Congenital Heart Disease", Diagnosis and Management of Adult Congenital Heart Disease (Third Edition), Elsevier, pp. 232–252, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-6929-1.00019-8, ISBN 978-0-7020-6929-1, retrieved 2020-11-11

- Issa, Ziad F.; Miller, John M.; Zipes, Douglas P. (2019-01-01), Issa, Ziad F.; Miller, John M.; Zipes, Douglas P. (eds.), "14 - Atrial Tachyarrhythmias in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease", Clinical Arrhythmology and Electrophysiology (Third Edition), Philadelphia: Elsevier, pp. 407–420, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-52356-1.00014-1, ISBN 978-0-323-52356-1, retrieved 2020-11-11

- Ottaviani, G.; Buja, L. M. (2016-01-01), Buja, L. Maximilian; Butany, Jagdish (eds.), "Chapter 15 - Congenital Heart Disease: Pathology, Natural History, and Interventions", Cardiovascular Pathology (Fourth Edition), San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 611–647, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-420219-1.00014-8, ISBN 978-0-12-420219-1, retrieved 2020-11-11