Child development

Child development involves the biological, psychological and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the conclusion of adolescence. Childhood is divided into 3 stages of life which include early childhood, middle childhood, and late childhood (preadolescence).[1] Early childhood typically ranges from infancy to the age of 6 years old. During this period, development is significant, as many of life's milestones happen during this time period such as first words, learning to crawl, and learning to walk. There is speculation that middle childhood/preadolescence or ages 6–12 [2] are the most crucial years of a child's life. Adolescence is the stage of life that typically starts around the major onset of puberty, with markers such as menarche and spermarche, typically occurring at 12–13 years of age.[3] It has been defined as ages 10 to 19 by the World Health Organization.[4] In the course of development, the individual human progresses from dependency to increasing autonomy. It is a continuous process with a predictable sequence, yet has a unique course for every child. It does not progress at the same rate and each stage is affected by the preceding developmental experiences. Because genetic factors and events during prenatal life may strongly influence developmental changes, genetics and prenatal development usually form a part of the study of child development. Related terms include developmental psychology, referring to development throughout the lifespan, and pediatrics, the branch of medicine relating to the care of children.

Developmental change may occur as a result of genetically controlled processes known as maturation,[5] or as a result of environmental factors and learning, but most commonly involves an interaction between the two. It may also occur as a result of human nature and of human ability to learn from the environment.

There are various definitions of periods in a child's development, since each period is a continuum with individual differences regarding starting and ending. Some age-related development periods and examples of defined intervals include: newborn (ages 0–4 weeks); infant (ages 1 month–1 year); toddler (ages 1–2 years); preschooler (ages 2–6 years); school-aged child (ages 6–12 years); adolescent (ages 12–18 years).[6]

Promoting child development through parental training, among other factors, promotes excellent rates of child development.[7] Parents play a large role in a child's activities, socialization, and development. Having multiple parents can add stability to a child's life and therefore encourage healthy development.[8] Another influential factor in children's development is the quality of their care. Child-care programs may be beneficial for childhood development such as learning capabilities and social skills.[9]

The optimal development of children is considered vital to society and it is important to understand the social, cognitive, emotional, and educational development of children. Increased research and interest in this field has resulted in new theories and strategies, with specific regard to practice that promotes development within the school system. Some theories seek to describe a sequence of states that compose child development.

Theories

Ecological systems

Also called "development in context" or "human ecology" theory, ecological systems theory, originally formulated by Urie Bronfenbrenner specifies four types of nested environmental systems, with bi-directional influences within and between the systems. The four systems are microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. Each system contains roles, norms, and rules that can powerfully shape development. Since its publication in 1979, Bronfenbrenner's major statement of this theory, The Ecology of Human Development[10] has had widespread influence on the way psychologists and others approach the study of human beings and their environments. As a result of this influential conceptualization of development, these environments — from the family to economic and political structures — have come to be viewed as part of the life course from childhood through adulthood.[11]

Piaget

Jean Piaget was a Swiss scholar who began his studies in intellectual development in the 1920s. Piaget's first interests were those that dealt with the ways in which animals adapt to their environments and his first scientific article about this subject was published when he was 10 years old. This eventually led him to pursue a Ph.D. in zoology, which then led him to his second interest in epistemology.[12] Epistemology branches off from philosophy and deals with the origin of knowledge. Piaget believed the origin of knowledge came from Psychology, so he travelled to Paris and began working on the first "standardized intelligence test" at Alfred Binet laboratories; this influenced his career greatly. As he carried out this intelligence testing he began developing a profound interest in the way children's intellectualism works. As a result, he developed his own laboratory and spent years recording children's intellectual growth and attempted to find out how children develop through various stages of thinking. This led Piaget to develop four important stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor stage (birth to age 2), preoperational stage (age 2 to 7), concrete-operational stage (ages 7 to 12), and formal-operational stage (ages 11 to 12, and thereafter).[12] Piaget concluded that adaption to an environment (behaviour) is managed through schemes and adaption occurs through assimilation and accommodation.

Stages

Sensorymotor: (birth to about age 2)

This is the first stage in Piaget's theory, where infants have the following basic senses: vision, hearing, and motor skills. In this stage, knowledge of the world is limited but is constantly developing due to the child's experiences and interactions.[13] According to Piaget, when an infant reaches about 7–9 months of age they begin to develop what he called object permanence, this means the child now has the ability to understand that objects keep existing even when they cannot be seen. An example of this would be hiding the child's favorite toy under a blanket, although the child cannot physically see it they still know to look under the blanket.

Preoperational: (begins about the time the child starts to talk, about age 2)

During this stage of development, young children begin analyzing their environment using mental symbols. These symbols often include words and images and the child will begin to apply these various symbols in their everyday lives as they come across different objects, events, and situations.[12] However, Piaget's main focus on this stage and the reason why he named it "preoperational" is because children at this point are not able to apply specific cognitive operations, such as mental math. In addition to symbolism, children start to engage in pretend play in which they pretend to be people they are not (teachers, superheroes). In addition, they sometimes use different props to make this pretend play more real.[12] Some deficiencies in this stage of development are that children who are about 3–4 years old often display what is called egocentrism, which means the child is not able to see someone else's point of view, they feel as if every other person is experiencing the same events and feelings that they are experiencing. However, at about 7, thought processes of children are no longer egocentric and are more intuitive, meaning they now think about the way something looks instead of rational thinking.[12]

Concrete: (about first grade to early adolescence)

During this stage, children between the age of 7 and 11 use appropriate logic to develop cognitive operations and begin applying this new thinking to different events they may encounter.[12] Children in this stage incorporate inductive reasoning, which involves drawing conclusions from other observations in order to make a generalization.[14] Unlike the preoperational stage, children can now change and rearrange mental images and symbols to form a logical thought, an example of this is reversibility in which the child now has the ability to reverse an action just by doing the opposite.[12]

Formal operations: (about early adolescence to mid/late adolescence)

The final stage of Piaget's cognitive development defines a child as now having the ability to "think more rationally and systematically about abstract concepts and hypothetical events".[12] Some positive aspects during this time is that child or adolescent begins forming their identity and begin understanding why people behave the way they behave. However, there are also some negative aspects which include the child or adolescent developing some egocentric thoughts which include the imaginary audience and the personal fable.[12] An imaginary audience is when an adolescent feels that the world is just as concerned and judgemental of anything the adolescent does as they are; an adolescent may feel as if they are "on stage" and everyone is a critic and they are the ones being critiqued.[12] A personal fable is when the adolescent feels that he or she is a unique person and everything they do is unique. They feel as if they are the only ones that have ever experienced what they are experiencing and that they are invincible and nothing bad will happen to them, it will only happen to others.[12]

Vygotsky

Vygotsky was a Russian theorist, who proposed the sociocultural theory. During the 1920s–1930s while Piaget was developing his own theory, Vygotsky was an active scholar and at that time his theory was said to be "recent" because it was translated out of Russian language and began influencing Western thinking.[12] He posited that children learn through hands-on experience, as Piaget suggested. However, unlike Piaget, he claimed that timely and sensitive intervention by adults when a child is on the edge of learning a new task (called the zone of proximal development) could help children learn new tasks. This technique is called "scaffolding," because it builds upon knowledge children already have with new knowledge that adults can help the child learn.[15] An example of this might be when a parent "helps" an infant clap or roll her hands to the pat-a-cake rhyme, until she can clap and roll her hands herself.[16][17]

Vygotsky was strongly focused on the role of culture in determining the child's pattern of development.[15] He argued that "Every function in the child's cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological). This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals."[15]

Vygotsky felt that development was a process and saw periods of crisis in child development during which there was a qualitative transformation in the child's mental functioning.[18]

Attachment

Attachment theory, originating in the work of John Bowlby and developed by Mary Ainsworth, is a psychological, evolutionary and ethological theory that provides a descriptive and explanatory framework for understanding interpersonal relationships between human beings. Bowlby's observations of close attachments led him to believe that close emotional bonds or "attachments" between an infant and their primary caregiver is an important requirement that is necessary to form "normal social and emotional development".[12]

Erik Erikson

Erikson, a follower of Freud's, synthesized both Freud's and his own theories to create what is known as the "psychosocial" stages of human development, which span from birth to death, and focuses on "tasks" at each stage that must be accomplished to successfully navigate life's challenges.[19]

Erikson's eight stages consist of the following:[20]

- Trust vs. mistrust (infant)

- Autonomy vs. shame (toddlerhood)

- Initiative vs. guilt (preschooler)

- Industry vs. inferiority (young adolescent)

- Identity vs. role confusion (adolescent)

- Intimacy vs. isolation (young adulthood)

- Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood)

- Ego integrity vs. despair (old age)

Behavioral

John B. Watson's behaviorism theory forms the foundation of the behavioral model of development 1925.[21] Watson was able to explain the aspects of human psychology through the process of classical conditioning. With this process, Watson believed that all individual differences in behavior were due to different learning experiences.[22] He wrote extensively on child development and conducted research (see Little Albert experiment). This experiment had shown that phobia could be created by classical conditioning. Watson was instrumental in the modification of William James' stream of consciousness approach to construct a stream of behavior theory.[23] Watson also helped bring a natural science perspective to child psychology by introducing objective research methods based on observable and measurable behavior.[23] Following Watson's lead, B.F. Skinner further extended this model to cover operant conditioning and verbal behavior.[24] Skinner used the operant chamber, or Skinner box, to observe the behavior of small organisms in a controlled situation and proved that organisms' behaviors are influenced by the environment. Furthermore, he used reinforcement and punishment to shape in desired behavior.

Other

In accordance with his view that the sexual drive is a basic human motivation,[25] Sigmund Freud developed a psychosexual theory of human development from infancy onward, divided into five stages.[26] Each stage centered around the gratification of the libido within a particular area, or erogenous zone, of the body.[27] He also argued that as humans develop, they become fixated on different and specific objects through their stages of development.[28][29] Each stage contains conflict which requires resolution to enable the child to develop.[30]

The use of dynamical systems theory as a framework for the consideration of development began in the early 1990s and has continued into the present century.[31] Dynamic systems theory stresses nonlinear connections (e.g., between earlier and later social assertiveness) and the capacity of a system to reorganize as a phase shift that is stage-like in nature. Another useful concept for developmentalists is the attractor state, a condition (such as teething or stranger anxiety) that helps to determine apparently unrelated behaviors as well as related ones.[32] Dynamic systems theory has been applied extensively to the study of motor development; the theory also has strong associations with some of Bowlby's views about attachment systems. Dynamic systems theory also relates to the concept of the transactional process,[33] a mutually interactive process in which children and parents simultaneously influence each other, producing developmental change in both over time.[34]

The "core knowledge perspective" is an evolutionary theory in child development that proposes "infants begin life with innate, special-purpose knowledge systems referred to as core domains of thought"[35] There are five core domains of thought, each of which is crucial for survival, which simultaneously prepare us to develop key aspects of early cognition; they are: physical, numerical, linguistic, psychological, and biological.[35]

Continuity and discontinuity

Although the identification of developmental milestones is of interest to researchers and to children's caregivers, many aspects of developmental change are continuous and do not display noticeable milestones of change.[36] Continuous developmental changes, like growth in stature, involve fairly gradual and predictable progress toward adult characteristics. When developmental change is discontinuous, however, researchers may identify not only milestones of development, but related age periods often called stages. A stage is a period of time, often associated with a known chronological age range, during which a behavior or physical characteristic is qualitatively different from what it is at other ages. When an age period is referred to as a stage, the term implies not only this qualitative difference, but also a predictable sequence of developmental events, such that each stage is both preceded and followed by specific other periods associated with characteristic behavioral or physical qualities.[37]

Stages of development may overlap or be associated with specific other aspects of development, such as speech or movement. Even within a particular developmental area, transition into a stage may not mean that the previous stage is completely finished. For example, in Erikson's discussion of stages of personality, this theorist suggests that a lifetime is spent in reworking issues that were originally characteristic of a childhood stage.[38] Similarly, the theorist of cognitive development, Piaget, described situations in which children could solve one type of problem using mature thinking skills, but could not accomplish this for less familiar problems, a phenomenon he called horizontal decalage.[39]

Mechanisms

Although developmental change runs parallel with chronological age,[40] age itself cannot cause development.[40] The basic mechanisms or causes of developmental change are genetic factors and environmental factors.[41] Genetic factors are responsible for cellular changes like overall growth, changes in proportion of body and brain parts,[42] and the maturation of aspects of function such as vision and dietary needs.[40] Because genes can be "turned off" and "turned on",[40] the individual's initial genotype may change in function over time, giving rise to further developmental change. Environmental factors affecting development may include both diet and disease exposure, as well as social, emotional, and cognitive experiences.[40] However, examination of environmental factors also shows that young human beings can survive within a fairly broad range of environmental experiences.[39]

Rather than acting as independent mechanisms, genetic and environmental factors often interact to cause developmental change.[40] Some aspects of child development are notable for their plasticity, or the extent to which the direction of development is guided by environmental factors as well as initiated by genetic factors.[40] When an aspect of development is strongly affected by early experience, it is said to show a high degree of plasticity; when the genetic make-up is the primary cause of development, plasticity is said to be low.[43] Plasticity may involve guidance by endogenous factors like hormones as well as by exogenous factors like infection.[40]

One kind of environmental guidance of development has been described as experience-dependent plasticity, in which behavior is altered as a result of learning from the environment. Plasticity of this type can occur throughout the lifespan and may involve many kinds of behavior, including some emotional reactions.[40] A second type of plasticity, experience-expectant plasticity, involves the strong effect of specific experiences during limited sensitive periods of development.[40] For example, the coordinated use of the two eyes, and the experience of a single three-dimensional image rather than the two-dimensional images created by light in each eye, depend on experiences with vision during the second half of the first year of life.[40] Experience-expectant plasticity works to fine-tune aspects of development that cannot proceed to optimum outcomes as a result of genetic factors working alone.[44][45]

In addition to the existence of plasticity in some aspects of development, genetic-environmental correlations may function in several ways to determine the mature characteristics of the individual. Genetic-environmental correlations are circumstances in which genetic factors make certain experiences more likely to occur.[40] For example, in passive genetic-environmental correlation, a child is likely to experience a particular environment because his or her parents' genetic make-up makes them likely to choose or create such an environment.[40] In evocative genetic-environmental correlation, the child's genetically caused characteristics cause other people to respond in certain ways, providing a different environment than might occur for a genetically different child;[40] for instance, a child with Down syndrome may be treated more protectively and less challengingly than a non-Down child.[40] Finally, an active genetic-environmental correlation is one in which the child chooses experiences that in turn have their effect;[40] for instance, a muscular, active child may choose after-school sports experiences that create increased athletic skills, but perhaps preclude music lessons. In all of these cases, it becomes difficult to know whether child characteristics were shaped by genetic factors, by experiences, or by a combination of the two.[46]

Asynchronous development

Asynchronous development occurs in cases when a child's cognitive, physical, and/or emotional development occur at different rates. Asynchronous development is common for gifted children when their cognitive development outpaces their physical and/or emotional maturity, such as when a child is academically advanced and skipping school grade levels yet still cries over childish matters and/or still looks his or her age. Asynchronous development presents challenges for schools, parents, siblings, peers, and the children themselves, such as making it hard for the child to fit in or frustrating adults who have become accustomed to the child's advancement in other areas.[47]

Research issues and methods

- What develops? What relevant aspects of the individual change over a period of time?

- What are the rate and speed of development?

- What are the mechanisms of development – what aspects of experience and heredity cause developmental change?

- Are there typical individual differences in the relevant developmental changes?

- Are there population differences in this aspect of development (for example, differences in the development of boys and of girls)?

Empirical research that attempts to answer these questions may follow a number of patterns. Initially, observational research in naturalistic conditions may be needed to develop a narrative describing and defining an aspect of developmental change, such as changes in reflex reactions in the first year.[48] This type of work may be followed by correlational studies, collecting information about chronological age and some type of development such as vocabulary growth; correlational statistics can be used to state change. Such studies examine the characteristics of children at different ages.[49] These methods may involve longitudinal studies, in which a group of children is re-examined on a number of occasions as they get older, or cross-sectional studies, in which groups of children of different ages are tested once and compared with each other, or there may be a combination of these approaches. Some child development studies examine the effects of experience or heredity by comparing characteristics of different groups of children in a necessarily non-randomized design. Other studies can use randomized designs to compare outcomes for groups of children who receive different interventions or educational treatments.[39]

Infant research methods

When conducting psychological research on infants and children, there are certain key aspects of infants that need to be considered before embarking on research.[50] Five key challenges to conducting research with infants are that infants cannot talk, have a limited behavioral repertoire, cannot follow instructions, have a short attention span, and develop rapidly (so methods need to be updated at different ages and developmental stages).[50]

High-amplitude sucking technique (HAS) is one common way to explore infants' preferences. HAS is appropriate for infants from the time that they are born until they are four months old since it takes advantage of infants' sucking reflex.[51] When this is a measure of interest, researchers will code a baseline sucking rate for each baby before exposing them to the item of interest. A common finding of HAS shows a relaxed, natural sucking rate when exposed to something the infant is familiar with, like their mother's voice, compared to an increased sucking rate around novel stimuli.[52]

The preferential-looking techique was a breakthrough made by Robert L. Fantz in 1961.[50] In his experiments, he would show the infants in his study two different stimuli. If an infant looks at one image longer than the other, there are two things that can be inferred: the infant can see that they are two different images and that the infant is showing preference to one image in some capacity. Depending on the goal of the experiment, infants may prefer to look at the novel and more interesting stimulus or they may look at the more comforting and familiar image.[53]

Eye tracking is a straightforward way of looking at infants' preferences. One example of eye tracking, using an eye tracking software, it is possible to see if infants understand commonly used nouns by tracking their eyes after they are cued with the target word.[54]

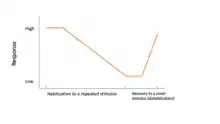

Another unique way to study infants' cognition is through habituation, which is the process of repeatedly showing a stimulus to an infant until they give no response.[55] Then, when infants are presented with a novel stimulus, they show a response. This violation of expectation reveals patterns of cognition and perception.[55] Using this study method, many different cognitive and perceptual ideas can be studied. Looking time is a common measure of habituation. Looking time is studied by recording how long an infant looks at a stimulus until they are habituated to that stimulus. Then, researchers record if an infant becomes dishabituated to a novel stimulus. This method can be used to measure preferences infants, including aesthetic preferences for certain colors.[56] Additionally, other discriminatory tasks can be studied, including auditory discrimination between different musical excerpts.[57]

Another way that children are studied is through brain imaging technology.[58] One example used a lot in child development studies is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). These machines can be used to track brain activity, growth, and connectivity in children[58][59] Brain development can be tracked from when a child is a fetus with this new technology.[59] Another common type of brain imaging can be collected with electroencephalography (EEG).[60] This technology can be used to diagnose seizures and encephalopathy, but considering conceptual age of the infant is important for analyzing the results.[60]

Ethical considerations

Most of the ethical challenges that exist in studies with adults exist within children. However, there are some notable differences in ethical research that should be addressed when designing studies for children.[61][62] An important consideration is that children should give their consent to participate in research. Because of the inherent power structure in most research settings, researchers must consider study designs that protect children from feeling coerced. Children are not allowed to give consent, so parents must give their informed consent for children to participate in research.[61] Children can give their assent, which should be reliably checked by both verbal and nonverbal cues throughout their participation.[61]

Milestones

Milestones are changes in specific physical and mental abilities (such as walking and understanding language) that mark the end of one developmental period and the beginning of another.[63] For stage theories, milestones indicate a stage transition. Studies of the accomplishment of many developmental tasks have established typical chronological ages associated with developmental milestones. However, there is considerable variation in the achievement of milestones, even between children with developmental trajectories within the typical range. Some milestones are more variable than others; for example, receptive speech indicators do not show much variation among children with typical hearing, but expressive speech milestones can be quite variable.[64]

A common concern in child development is developmental delay involving a delay in an age-specific ability for important developmental milestones. Prevention of and early intervention in developmental delay are significant topics in the study of child development.[65] Developmental delays should be diagnosed by comparison with characteristic variability of a milestone, not with respect to average age at achievement. An example of a milestone would be eye-hand coordination, which includes a child's increasing ability to manipulate objects in a coordinated manner.

There is a phenomenal growth or exponential increase of child development from the age of 4 to 15 years old especially during the age of 4 to 7 years old based on the Yamana chart [66]). The Heckman's chart shows that the highest return of investment in education is maximum during the early years (age 1 to 3 years old) and decreases to a plateau during the school-aged years and adolescence.[66] There are various child development tables or charts e.g. the PILES table where PILES stands for Physical, Intellectual, Language, Emotional and Social development aspects.[67]

Aspects

Child development is not a matter of a single topic, but progresses somewhat differently for different aspects of the individual. Here are descriptions of the development of a number of physical and mental characteristics.

Physical growth

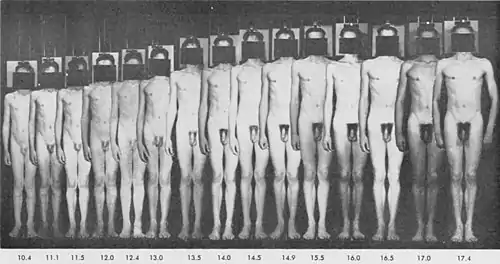

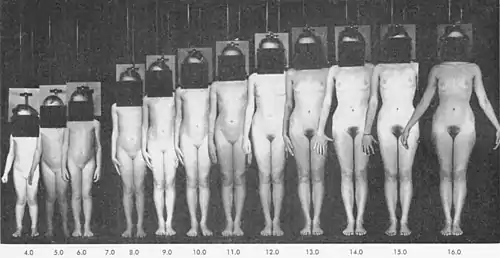

| For North American, Indo-Iranian (India, Iran), and European girls | For North American, Indo-Iranian (India, Iran), and European boys |

|---|---|

|

Physical growth in stature and weight occurs over the 15–20 years following birth, as the individual changes from the average weight of 3.5 kg and length of 50 cm at full term birth to full adult size. As stature and weight increase, the individual's proportions also change, from the relatively large head and small torso and limbs of the neonate, to the adult's relatively small head and long torso and limbs.[68] The child's pattern of growth is in a head-to-toe direction, or cephalocaudal, and in an inward to outward pattern (center of the body to the peripheral) called proximodistal.

Speed and pattern

The speed of physical growth is rapid in the months after birth, then slows, so birth weight is doubled in the first four months, tripled by age 12 months, but not quadrupled until 24 months.[69] Growth then proceeds at a slow rate until shortly before puberty (between about 9 and 15 years of age), when a period of rapid growth occurs.[70] Growth is not uniform in rate and timing across all body parts. At birth, head size is already relatively near to that of an adult, but the lower parts of the body are much smaller than adult size. In the course of development, then, the head grows relatively little, and torso and limbs undergo a great deal of growth.[68]

Mechanisms of change

Genetic factors play a major role in determining the growth rate, and particularly the changes in proportion characteristic of early human development. However, genetic factors can produce maximum growth only if environmental conditions are adequate. Poor nutrition and frequent injury and disease can reduce the individual's adult stature, but the best environment cannot cause growth to a greater stature than is determined by heredity.[68]

Individual variation versus disease

Individual differences in height and weight during childhood are considerable. Some of these differences are due to family genetic factors, others to environmental factors, but at some points in development they may be strongly influenced by individual differences in reproductive maturation.[68]

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists defines short stature as height more than 2 standard deviations below the mean for age and gender, which corresponds to the shortest 2.3% of individuals.[71] In contrast, failure to thrive is usually defined in terms of weight, and can be evaluated either by a low weight for the child's age, or by a low rate of increase in the weight.[72] A similar term, stunted growth, generally refers to reduced growth rate as a manifestation of malnutrition in early childhood.

Motor

Abilities for physical movement change through childhood from the largely reflexive (unlearned, involuntary) movement patterns of the young infant to the highly skilled voluntary movements characteristic of later childhood and adolescence.

Definition

"Motor learning refers to the increasing spatial and temporal accuracy of movements with practice".[73] Motor skills can be divided into two categories: first as basic skills necessary for everyday life and secondly, as recreational skills such as skills for employment or certain specialties based on interest.

Speed and pattern

The speed of motor development is rapid in early life, as many of the reflexes of the newborn alter or disappear within the first year, and slow later. Like physical growth, motor development shows predictable patterns of cephalocaudal (head to foot) and proximodistal (torso to extremities) development, with movements at the head and in the more central areas coming under control before those of the lower part of the body or the hands and feet. Types of movement develop in stage-like sequences;[74] for example, locomotion at 6–8 months involves creeping on all fours, then proceeds to pulling to stand, "cruising" while holding on to an object, walking while holding an adult's hand, and finally walking independently.[74] By middle childhood and adolescence, new motor skills are acquired by instruction or observation rather than in a predictable sequence.[36] There are executive functions of the brain (working memory, timing measure of inhibition and switching) which are important to motor skills. Critiques to the order of Executive Functioning leads to Motor Skills, suggesting Motor Skills can support Executive Functioning in the brain.

Mechanisms

The mechanisms involved in motor development involve some genetic components that determine the physical size of body parts at a given age, as well as aspects of muscle and bone strength. The main areas of the brain involved in motor skills are the frontal cortex, parietal cortex and basal ganglia. The dorsolateral frontal cortex is responsible for strategic processing. The parietal cortex is important in controlling perceptual-motor integration and the basal ganglia and supplementary motor cortex are responsible for motor sequences.

According to a study showing the different relationships between limbs of the body and coordination in infants, genetic components have a huge impact on motor development (Piek, Gasson, Barrett, & Case (2002)). Intra-limb correlations, like the strong relationship and distance between hip and knee joints, were studied and proved to affect the way an infant will walk. There are also bigger genetic factors like the tendency to use the left or right side of the body more, predicting the dominant hand early. Sample t-tests proved that there was a significant difference between both sides at 18 weeks for girls and the right side was considered to be more dominant (Piek et al. (2002)). Some factors, like the fact that boys tend to have larger and longer arms are biological constraints that we cannot control, yet have an influence for example, on when an infant will reach sufficiently. Overall, there are sociological factors and genetic factors that influence motor development.[75]

Nutrition and exercise also determine strength and therefore the ease and accuracy with which a body part can be moved.[36] Flexibility is also affected by nutrition and exercise as well.[76] It has also been shown that the frontal lobe develops posterio-anteriorally (from back to front). This is significant in motor development because the hind portion of the frontal lobe is known to control motor functions. This form of development is known as "Portional Development" and explains why motor functions develop relatively quickly during typical childhood development, while logic, which is controlled by the middle and front portions of the frontal lobe, usually will not develop until late childhood and early adolescence.[77] Opportunities to carry out movements help establish the abilities to flex (move toward the trunk) and extend body parts, both capacities are necessary for good motor ability. Skilled voluntary movements such as passing objects from hand to hand develop as a result of practice and learning.[36] Mastery Climate is a suggested successful learning environment for children to promote motor skills by their own motivation. This promotes participation and active learning in children, which according to Piaget's theory of cognitive development is extremely important in early childhood rule.

Individual differences

Typical individual differences in motor ability are common and depend in part on the child's weight and build. Infants with smaller, slimmer, and more maturely proportionated builds tended to belly crawl and crawl earlier than the infants with larger builds. Infants with more motor experience have been shown to belly crawl and crawl sooner. Not all infants go through the stages of belly crawling. However, those who skip the stage of belly crawling are not as proficient in their ability to crawl on their hands and knees.[78] After the infant period, typical individual differences are strongly affected by opportunities to practice, observe, and be instructed on specific movements. Atypical motor development such as persistent primitive reflexis beyond 4–6 months or delayed walking may be an indication of developmental delays or conditions such as autism, cerebral palsy, or down syndrome .[36] Lower motor coordination results in difficulties with speed accuracy and trade-off in complex tasks.

Children with disabilities

Children with Down syndrome or Developmental coordination disorder are late to reach major motor skills milestones. A few examples of these milestones are sucking, grasping, rolling, sitting up and walking, talking. Children with Down syndrome sometimes have heart problems, frequent ear infections, hypotonia, or undeveloped muscle mass. This syndrome is caused by atypical chromosomal development. Along with Down syndrome, children can also be diagnosed with a learning disability. Learning Disabilities include disabilities in any of the areas related to language, reading, and mathematics. Basic reading skills is the most common learning disability in children, which, like other disabilities, focuses on the difference between a child's academic achievement and his or her apparent capacity to learn.[79]

Population differences

Regardless of the culture a baby is born into, they are born with a few core domains of knowledge. These principals allow him or her to make sense of their environment and learn upon previous experience by using motor skills such as grasping or crawling. There are some population differences in motor development, with girls showing some advantages in small muscle usage, including articulation of sounds with lips and tongue. Ethnic differences in reflex movements of newborn infants have been reported, suggesting that some biological factor is at work. Cultural differences may encourage learning of motor skills like using the left hand only for sanitary purposes and the right hand for all other uses, producing a population difference.[80] Cultural factors are also seen at work in practiced voluntary movements such as the use of the foot to dribble a soccer ball or the hand to dribble a basketball.[36]

Cognitive/intellectual

Cognitive development is primarily concerned with ways in which young children acquire, develop, and use internal mental capabilities such as problem-solving, memory, and language.

Mechanisms

Cognitive development has genetic and other biological mechanisms, as is seen in the many genetic causes of intellectual disability. Environmental factors including food and nutrition, the responsiveness of parents, daily experiences, physical activity and love can influence early brain development of children.[81] However, although it is assumed that brain functions cause cognitive events, it has not been possible to measure specific brain changes and show that they cause cognitive change. Developmental advances in cognition are also related to experience and learning, and this is particularly the case for higher-level abilities like abstraction, which depend to a considerable extent on formal education.[36]

Speed and pattern

The ability to learn temporal patterns in sequenced actions was investigated in elementary-school-age children. Temporal learning depends upon a process of integrating timing patterns with action sequences. Children ages 6–13 and young adults performed a serial response time task in which a response and a timing sequence were presented repeatedly in a phase-matched manner, allowing for integrative learning. The degree of integrative learning was measured as the slowing in performance that resulted when phase-shifting the sequences. Learning was similar for the children and adults on average but increased with age for the children. Executive function measured by Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) performance as well as a measure of response speed also improved with age. Finally, WCST performance and response speed predicted temporal learning. Taken together, the results indicate that temporal learning continues to develop in pre-adolescents and that maturing executive function or processing speed may play an important role in acquiring temporal patterns in sequenced actions and the development of this ability.[82]

Individual differences

There are typical individual differences in the ages at which specific cognitive abilities are achieved,[36] but schooling for children in industrialized countries is based on the assumption that these differences are not large.[36] Atypical delays in cognitive development are problematic for children in cultures that demand advanced cognitive skills for work and for independent living.[36]

Population differences

There are few population differences in cognitive development.[36] Boys and girls show some differences in their skills and preferences, but there is a great deal of overlap between the groups.[36] Differences in cognitive achievement of different ethnic groups appears to result from cultural or other environmental factors.[36]

Social-emotional

Factors

Newborn infants do not seem to experience fear or have preferences for contact with any specific people. In the first few months they only experience happiness, sadness, and anger. A baby's first smile usually occurs between 6 and 10 weeks. It is called a 'social smile' because it usually occurs during social interactions.[83] By about 8–12 months, they go through a fairly rapid change and become fearful of perceived threats; they also begin to prefer familiar people and show anxiety and distress when separated from them or approached by strangers.

Separation anxiety is a typical stage of development to an extent. Kicking, screaming, and throwing temper tantrums are perfectly typical symptoms for separation anxiety. Depending on the level of intensity, one may determine whether or not a child has separation anxiety disorder. This is when a child constantly refuses to separate from the parent, but in an intense manner. This can be given special treatment but the parent usually cannot do anything about the situation.[84]

The capacity for empathy and the understanding of social rules begin in the preschool period and continue to develop into adulthood. Middle childhood is characterized by friendships with age-mates, and adolescence by emotions connected with sexuality and the beginnings of romantic love.[36] Anger seems most intense during the toddler and early preschool period and during adolescence.[36]

Speed and pattern

Some aspects of social-emotional development, like empathy, develop gradually, but others, like fearfulness, seem to involve a rather sudden reorganization of the child's experience of emotion.[36] Sexual and romantic emotions develop in connection with physical maturation.[36]

Mechanisms

Genetic factors appear to regulate some social-emotional developments that occur at predictable ages, such as fearfulness, and attachment to familiar people. Experience plays a role in determining which people are familiar, which social rules are obeyed, and how anger is expressed.[36]

Parenting practices have been shown to predict children's emotional intelligence. The objective is to study the time mothers and children spent together in joint activity, the types of activities that they develop when they are together, and the relation that those activities have with the children's trait emotional intelligence. Data was collected for both mothers and children (N = 159) using self-report questionnaires. Correlations between time variables and trait emotional intelligence dimensions were computed using Pearson's Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient. Partial correlations between the same variables controlling for responsive parenting were also computed. The amount of time mothers spent with their children and the quality of their interactions are important in terms of children's trait emotional intelligence, not only because those times of joint activity reflect a more positive parenting, but because they are likely to promote modeling, reinforcement, shared attention, and social cooperation.[85]

Population differences

Population differences may occur in older children, if, for example, they have learned that it is appropriate for boys to express emotion or behave differently from girls,[86] or if customs learned by children of one ethnic group are different from those learned in another.[86] Social and emotional differences between boys and girls of a given age may also be associated with differences in the timing of puberty characteristic of the two sexes.[36]

Gender

Gender identity involves how a person perceives themselves as male, female, or a variation of the two. Children can identify themselves as belonging to a certain gender as early as two years old,[87] but how gender identity is developed is a topic of scientific debate. Several factors are involved in determining an individual's gender, including: neonatal hormones, postnatal socialization, and genetic influences.[88] Some believe that gender is malleable until late childhood,[88] while others argue that gender is established early and gender-typed socialization patterns either reinforce or soften the individual's notion of gender.[89] Since most people identify as the gender that is typically associated to their genitalia, studying the impact of these factors is difficult. Evidence suggests that neonatal androgens, male sex hormones produced in the womb during gestation, play an important role. Testosterone in the womb directly codes the brain for either male or female-typical development. This includes both the physical structure of the brain and the characteristics the person expresses because of it. Persons exposed to high levels of testosterone during gestation typically develop a male gender identity while those who are not or those who do not possess the receptors necessary to interact with these hormones typically develop a female gender identity.[88][90] An individual's genes are also thought to interact with the hormones during gestation and in turn affect gender identity, but the genes responsible for this and their effects have not been precisely documented and evidence is limited.[90] It is unknown whether socialization plays a part in determining gender identity postnatally. It is well documented that children actively seek out information on how to properly interact with others based on their gender,[89] but the extent to which these role models, which can include parents, friends, and TV characters, influence gender identity is less clear and no consensus has been reached.

Race

In addition to the course of development, previous literature has looked at how race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status has affected child development. Some studies seem to speak to the importance of adult supervision of adolescent youth.[91] Literature suggested that African Americans child development was sometimes differentiated on the basis of cultural socialization and racial socialization. Further, a different study found that immigrant youth tended to choose majors focusing on the fields of science and math more often than not.

Mechanisms

Language serves the purpose of communication to express oneself through a systematic and traditional use of sounds, signs, or written symbols.[92] There are four subcomponents in which the child must attain in order to acquire language competence. They include phonology, lexicon, morphology and syntax, and pragmatics.[93] These subcomponents of language development are combined to form the components of language, which are sociolinguistics and literacy.[92] Currently, there is no single accepted theory of language acquisition but various explanations of language development have been accumulated.

Components

The four components of language development include:

- Phonology is concerned with the sounds of language.[94] It is the function, behavior, and organization of sounds as linguistic items.[95] Phonology considers what the sounds of language are and what the rules are for combining sounds. Phonological acquisition in children can be measured by accuracy and frequency of production of various vowels and consonants, the acquisition of phonemic contrasts and distinctive features, or by viewing development in regular stages in their own speech sound systems and to characterize systematic strategies they adopt.[96]

- Lexicon is a complex dictionary of words that enables language speakers to use these words in speech production and comprehension.[97] Lexicon is the inventory of a language's morphemes. Morphemes act as minimal meaning-bearing elements or building blocks of something in language that makes sense. For example, in the word "cat", the component "cat" makes sense as does "at", but "at" does not mean the same thing as "cat". In this example, "ca" does not mean anything.

- Morphology is the study of form or forms. It is the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure and how they are formed.[98]

- Pragmatics is the study of relationships between linguistic forms and the users of those forms.[99] It also incorporates the use of utterance to serve different functions and can be defined as the ability to communicate one's feelings and desires to others.[100]

Children's development of language also includes semantics which is the attachment of meaning to words. This happens in three stages. First, each word means an entire sentence. For example, a young child may say "mama" but the child may mean "Here is Mama", "Where is Mama?", or "I see Mama." In the second stage, words have meaning but do not have complete definitions. This stage occurs around age two or three. Third, around age seven or eight, words have adult-like definitions and their meanings are more complete.[101]

A child learns the syntax of their language when they are able to join words together into sentences and understand multiple-word sentences said by other people. There appear to be six major stages in which a child's acquisition of syntax develops.[102] First, is the use of sentence-like words in which the child communicates using one word with additional vocal and bodily cues. This stage usually occurs between 12 and 18 months of age. Second, between 18 months to two years, there is the modification stage where children communicate relationships by modifying a topic word. The third stage, between two and three years old, involves the child using complete subject-predicate structures to communicate relationships. Fourth, children make changes on basic sentence structure that enables them to communicate more complex relationships. This stage occurs between the ages of two and a half years to four years. The fifth stage of categorization involves children aged three and a half to seven years refining their sentences with more purposeful word choice that reflects their complex system of categorizing word types. Finally, children use structures of language that involve more complicate syntactic relationships between the ages of five years old to ten years old.[102]

Milestones

Infants begin with cooing and soft vowel sounds. Shortly after birth, this system is developed as the infants begin to understand that their noises, or non-verbal communication, lead to a response from their caregiver.[103] This will then progress into babbling around 5 months of age, with infants first babbling consonant and vowel sounds together that may sound like "ma" or "da".[104] At around 8 months of age, babbling increases to include repetition of sounds, such as "da-da" and infants learn the forms for words and which sounds are more likely to follow other sounds.[104] At this stage, much of the child's communication is open to interpretation. For example, if a child says "bah" when they're in a toy room with their guardian, it is likely to be interpreted as "ball" because the toy is in sight. However, if you were to listen to the same 'word' on a recorded tape without knowing the context, one might not be able to figure out what the child was trying to say.[103] A child's receptive language, the understanding of others' speech, has a gradual development beginning at about 6 months.[105] However, expressive language, the production of words, moves rapidly after its beginning at about a year of age, with a "vocabulary explosion" of rapid word acquisition occurring in the middle of the second year.[105] Grammatical rules and word combinations appear at about age two.[105] Between 20 and 28 months, children move from understanding the difference between high and low, hot and cold and begin to change "no" to "wait a minute", "not now" and "why". Eventually, they are able to add pronouns to words and combine them to form short sentences.[103] Mastery of vocabulary and grammar continue gradually through the preschool and school years.[105] Adolescents still have smaller vocabularies than adults and experience more difficulty with constructions such as the passive voice.[105]

By age 1, the child is able to say 1–2 words, responds to its name, imitates familiar sounds and can follow simple instructions.[104] Between 1–2 years old, the child uses 5–20 words, is able to say 2-word sentences and is able to express their wishes by saying words like "more" or "up", and they understand the word "no".[104] During 2 and 3 years of age, the child is able to refer to itself as "me", combine nouns and verbs, has a vocabulary of about 450 words, use short sentences, use some simple plurals and is able to answer "where" questions.[104] By age 4, children are able to use sentences of 4–5 words and has a vocabulary of about 1000 words.[104] Children between the ages of 4 and 5 years old are able to use past tense, have a vocabulary of about 1,500 words, and ask questions like "why?" and "who?".[104] By age 6, the child has a vocabulary of 2,600 words, is able to form sentences of 5–6 words and use a variety of different types of sentences.[104] By the age of 5 or 6 years old, the majority of children have mastered the basics of their native language.[104] Infants, 15 month-olds, are initially unable to understand familiar words in their native language pronounced using an unfamiliar accent.[106] This means that a Canadian-English speaking infant cannot recognize familiar words pronounced with an Australian-English accent. This skill develops close to their second birthdays.[106] However, this can be overcome when a highly familiar story is read in the new accent prior to the test, suggesting the essential functions of underlying spoken language is in place before previously thought.[106]

Vocabulary typically grows from about 20 words at 18 months to around 200 words at 21 months.[105] From around 18 months the child starts to combine words into two-word sentences.[105] Typically the adult expands it to clarify meaning.[105] By 24–27 months the child is producing three or four-word sentences using a logical, if not strictly correct, syntax.[105] The theory is that children apply a basic set of rules such as adding 's' for plurals or inventing simpler words out of words too complicated to repeat like "choskit" for chocolate biscuit.[105] Following this there is a rapid appearance of grammatical rules and ordering of sentences.[105] There is often an interest in rhyme, and imaginative play frequently includes conversations. Children's recorded monologues give insight into the development of the process of organizing information into meaningful units.[105]

By three years the child begins to use complex sentences, including relative clauses, although still perfecting various linguistic systems.[105] By five years of age the child's use of language is very similar to that of an adult.[105] From the age of about three children can indicate fantasy or make-believe linguistics, produce coherent personal stories and fictional narrative with beginnings and endings.[105] It is argued that children devise narrative as a way of understanding their own experience and as a medium for communicating their meaning to others.[105] The ability to engage in extended discourse emerges over time from regular conversation with adults and peers. For this, the child needs to learn to combine his perspective with that of others and with outside events and learn to use linguistic indicators to show he is doing this. They also learn to adjust their language depending on to whom they are speaking.[105] Typically by the age of about 9 a child can recount other narratives in addition to their own experiences, from the perspectives of the author, the characters in the story and their own views.[105]

Sequential skill in learning to talk

| Child Age in Months | Language Skill |

|---|---|

| 0–3 | Vocal play: cry, coo, gurgle, grunt |

| 3– | Babble: undifferentiated sounds |

| 6–10 | Babble: canonical/reduplicated syllables |

| 9- | Imitation |

| 8–18 | First words |

| 13–15 | Expressive jargon, intonational sentences |

| 13–19 | 10-word vocabulary |

| 14–24 | 50-word vocabulary |

| 13–27 | Single-word stage and a few sentences, two-to-three-word combinations, Articles: a/the, Plural: -s |

| 23–24 | Irregular past: went, modal and verb: can/will, 28 to 436-word vocabulary, 93–265 utterances per hour |

| 25–27 | Regular past: -ed, Auxiliary "be": -'m, -'s |

| 23–26 | Third-person singular: -s, 896 to 1 507-word vocabulary, 1 500 to 1 700 words per hour |

Theories

Although the role of adult discourse is important in facilitating the child's learning, there is considerable disagreement among theorists about the extent to which children's early meanings and expressive words arise. Findings about the initial mapping of new words, the ability to decontextualize words, and refine meaning of words are diverse.[11] One hypothesis is known as the syntactic bootstrapping hypothesis which refers to the child's ability to infer meaning from cues, using grammatical information from the structure of sentences.[108] Another is the multi-route model in which it is argued that context-bound words and referential words follow different routes; the first being mapped onto event representations and the latter onto mental representations. In this model, parental input has a critical role but the children ultimately rely on cognitive processing to establish subsequent use of words.[109] However, naturalistic research on language development has indicated that preschoolers' vocabularies are strongly associated with the number of words addressed to them by adults.[110]

There is no single accepted theory of language acquisition. Instead, there are current theories that help to explain theories of language, theories of cognition, and theories of development. They include the generativist theory, social interactionist theory, usage-based theory (Tomasello), connectionist theory, and behaviorist theory (Skinner). Generativist theories refer to Universal Grammar being innate where language experience activates innate knowledge.[111] Social interactionist theories define language as a social phenomenon. This theory states that children acquire language because they want to communicate with others; this theory is heavily based on social-cognitive abilities that drive the language acquisition process.[111] Usage-based theories define language as a set of formulas that emerge from the child's learning abilities in correspondence with its social cognitive interpretation and understanding of the speakers' intended meanings.[111] Connectionist theories is a pattern-learning procedure and defines language as a system composed of smaller subsystems or patterns of sound or meaning.[111] Behaviorist theories define language as the establishment of positive reinforcement, but is now regarded a theory of historical interest.[111]

Language

Communication can be defined as the exchange and negotiation of information between two or more individuals through verbal and nonverbal symbols, oral and written (or visual) modes, and the production and comprehension processes of communication.[112] According to First International Congress for the Study of Child Language, "the general hypothesis [is that] access to social interaction is a prerequisite to normal language acquisition".[113] Principles of conversation include two or more people focusing on one topic. All questions in a conversation should be answered, comments should be understood or acknowledged and any form of direction should, in theory, be followed. In the case of young, undeveloped children, these conversations are expected to be basic or redundant. The role of a guardians during developing stages is to convey that conversation is meant to have a purpose, as well as teaching them to recognize the other speaker's emotions.[113] Communicative language is nonverbal and/or verbal, and to achieve communication competence, four components must be met. These four components of communication competence include: grammatical competence (vocabulary knowledge, rules of word sentence formation, etc.), sociolinguistic competence (appropriateness of meanings and grammatical forms in different social contexts), discourse competence (knowledge required to combine forms and meanings), and strategic competence (knowledge of verbal and nonverbal communication strategies).[112] The attainment of communicative competence is an essential part of actual communication.[114]

Language development is viewed as a motive to communication, and the communicative function of language in-turn provides the motive for language development. Jean Piaget uses the term "acted conversations" to explain a child's style of communication that rely more heavily on gestures and body movements, rather than words.[102] Younger children depend on gestures for a direct statement of their message. As they begin to acquire more language, body movements take on a different role and begin to complement the verbal message.[102] These nonverbal bodily movements allow children to express their emotions before they can express them verbally. The child's nonverbal communication of how they're feeling is seen in babies 0 to 3 months who use wild, jerky movements of the body to show excitement or distress.[102] This develops to more rhythmic movements of the entire body at 3 to 5 months to demonstrate the child's anger or delight.[102] Between 9–12 months of age, children view themselves as joining the communicative world.[92] Before 9–12 months, babies interact with objects and interact with people, but they do not interact with people about objects. This developmental change is the change from primary intersubjectivity (capacity to share oneself with others) to secondary intersubjectivity (capacity to share one's experience), which changes the infant from an unsociable to socially engaging creature.[92] Around 12 months of age a communicative use of gesture is used. This gesture includes communicative pointing where an infant points to request something, or to point to provide information.[92] Another gesture of communication is presented around the age of 10 and 11 months where infants start gaze-following; they look where another person is looking.[92] This joint attention result in changes to their social cognitive skills between the ages of 9 and 15 months as their time is spent increasingly with others.[92] Children's use of non-verbal communicative gestures foretells future language development. The use of non-verbal communication in the form of gestures indicate the child's interest in communication development, and the meanings they choose to convey that are soon revealed through the verbalization of language.[92]

Language acquisition and development contribute to the verbal form of communication. Children originate with a linguistic system where words they learn, are the words used for functional meaning.[111] This instigation of speech has been termed pragmatic bootstrapping. According to this, children view words as a means of social construction, and that words are used to connect the understanding of communicative intentions of the speaker who speaks a new word.[111] Hence, the competence of verbal communication through language is achieved through the attainability of syntax or grammar. Another function of communication through language is pragmatic development.[115] Pragmatic development includes the child's intentions of communication before he/she knows how to express these intentions, and throughout the first few years of life both language and communicative functions develop.[111]

When children acquire language and learn to use language for communicative functions (pragmatics), children also gain knowledge about the participation in conversations and relating to past experiences/events (discourse knowledge), and how to use language appropriately in congruence with their social situation or social group (sociolinguistic knowledge).[111] Within the first two years of life, a child's language ability progresses and conversational skills, such as the mechanics of verbal interaction, develop. Mechanics of verbal interaction include taking turns, initiating topics, repairing miscommunication, and responding to lengthen or sustain dialogue.[111] Conversation is asymmetrical when a child interacts with an adult because the adult is the one to create structure in the conversation, and to build upon the child's contributions. In accordance to the child's developing conversational skills, asymmetrical conversation between adult and child modulate to an equal temperament of conversation. This shift in balance of conversation suggests a narrative discourse development in communication.[111] Ordinarily, the development of communicative competence and the development of language are positively correlated with one another,[111] however, the correlation is not flawless.

Individual differences

Delays in language is the most frequent type of developmental delay. According to demographics 1 out of 5 children will learn to talk or use words later than other children their age. Speech/language delay is three to four times more common in boys than in girls. Some children will also display behavioral problems due to their frustration of not being able to express what they want or need.

Simple speech delays are usually temporary. Most cases are solved on their own or with a little extra attribution from the family. It's the parent's duty to encourage their baby to talk to them with gestures or sounds and for them to spend a great amount of time playing with, reading to, and communicating with their baby. In certain circumstances, parents will have to seek professional help, such as a speech therapist.

It is important to take into considerations that sometimes delays can be a warning sign of more serious conditions that could include auditory processing disorders, hearing loss, developmental verbal dyspraxia, developmental delay in other areas, or even an autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Environmental causes

There are many environmental causes that are linked to language delays and they include situations such as, the child is having their full attention on other skills, such as walking perfectly, rather than on language. The child may have a twin or a sibling in which their age are relatively close, and may not be receiving the parent's full attention. Another circumstance could be a child that is in a daycare that provides few adults to be able to administer individual attention. Perhaps the most obvious component would be a child that suffers from psychosocial deprivation such as poverty, malnutrition, poor housing, neglect, inadequate linguistic stimulation, or emotional stress.

Neurological causes

Language delay can be caused by a substantial number of underlying disorders, such as intellectual disability. Intellectual disability takes part for more than 50 percent of language delays. Language delay is usually more rigorous than other developmental delays in intellectually disabled children, and it is usually the first obvious symptom of intellectual disability. Intellectual disability accounts to global language delay, including delayed auditory comprehension and use of gestures.

Impaired hearing is one of the most common causes of language delay. A child who can not hear or process speech in a clear and consistent manner will have a language delay. Even the most minimum hearing impairment or auditory processing deficit can considerably affect language development. Essentially, the more the severe the impairment, the more serious the language delay. Nevertheless, deaf children that are born to families who use sign language develop infant babble and use a fully expressive sign language at the same pace as hearing children.

Developmental Dyslexia is a developmental reading disorder that occurs when the brain does not properly recognize and process the graphic symbols chosen by society to represent the sounds of speech. Children with dyslexia may encounter problems in rhyming and separating sounds that compose words. These abilities are essential in learning to read. Early reading skills rely heavily on word recognition. When using an alphabet writing system this involves in having the ability to separate out the sounds in words and be able to match them with letter and groups of letters. Because they have trouble in connecting sounds of language to the letter of words, this may result difficulty in understanding sentences. They have confusion in mistaking letters such as "b" and "d". For the most part, symptoms of dyslexia may include, difficulty in determining the meaning of a simple sentence, learning to recognize written words, and difficulty in rhyming.

Autism and speech delay are usually correlated. Problems with verbal language are the most common signs seen in autism. Early diagnosis and treatment of autism can significantly help the child improve their speech skills. Autism is recognized as one of the five pervasive developmental disorders, distinguished by problems with language, speech, communication and social skills that present in early childhood. Some common autistic syndromes are the following, being limited to no verbal speech, echolalia or repeating words out of context, problems responding to verbal instruction and may ignore others who speak directly.

Risk factors

Malnutrition, maternal depression, and maternal substance use are three of these factors which have received particular attention by researchers, however, many more factors have been considered.[116][117][118]

Postnatal depression

Although there are a large number of studies contemplating the effect of maternal depression and postnatal depression of various areas of infant development, they are yet to come to a consensus regarding the true effects. There are numerous studies indicating impaired development, and equally, there are many proclaiming no effect of depression on development. A study of 18-month-olds whose mothers had depressive symptoms while they were 6 weeks and/or 6 months old indicated that maternal depression had no effect on the child's cognitive development at 18 months.[119] Furthermore, the study indicates that maternal depression combined with a poor home environment is more likely to have an effect on cognitive development. However, the authors conclude that it may be that short term depression has no effect, where as long term depression could cause more serious problems. A further longitudinal study spanning 7 years again indicate no effect of maternal depression on cognitive development as a whole, however it found a gender difference in that boys are more susceptible to cognitive developmental issues when their mothers had depression.[117] This thread is continued in a study of children up to 2 years old.[120] The study reveals a significant difference on cognitive development between genders, with girls having a higher score, however this pattern is found regardless of the child's mother's history of depression. Infants with chronically depressed mothers showed significantly lower scores on the motor and mental scales within the Bayley Scales of Infant Development,[120] contrasting with many older studies.[117][119] A similar effect has been found at 11 years: male children of depressed mothers score an average of 19.4 points lower on an Intelligence Quotient IQ test than those with healthy mothers, although this difference is much lower in girls.[121] 3 month olds with depressed mothers show significantly lower scores on the Griffiths Mental Development Scale, which covers a range of developmental areas including cognitive, motor and social development.[122] It has been suggested that interactions between depressed mothers and their children may affect social and cognitive abilities in later life.[123] Maternal depression has been shown to influence the mothers' interaction with her child.[124] When communicating with their child, depressed mothers fail to make changes to their vocal behaviour, and tend use unstructured vocal behaviours.[125] Furthermore, when infants interact with depressed mothers they show signs of stress, such as increased pulse and raised cortisol levels, and make more use of avoidance behaviours, for example looking away, compared to those interacting with healthy mothers.[123] The effect of mother-infant interaction at 2 months has been shown to affect the child's cognitive performance at 5 years.[126] Recent studies have begun to identify that other forms of psychopathology that may or may not be co-morbidly occurring with maternal depression can independently influence infants' and toddlers' subsequent social-emotional development through effects on regulatory processes within the child-parent attachment.[127] Maternal interpersonal violence-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for example, has been associated with subsequent dysregulation of emotion and aggression by ages 4–7 years.[128]

Cocaine

Research has provided conflicting evidence regarding the effect of maternal substance use during and after pregnancy on children's development.[118] Children exposed to cocaine weigh less than those not exposed at numerous ages ranging from 6 to 30 months.[129] Furthermore, studies indicate that the head circumference of children exposed to cocaine is lower than those unexposed.[129][130] On the other hand, two more recent studies found no significant differences between those exposed to cocaine and those who were not in either measure.[131][132]

Maternal cocaine use may also affect the child's cognitive development, with exposed children achieving lower scores on measures of psychomotor and mental development.[133][134] However, again there is conflicting evidence, and a number of studies indicate no effect of maternal cocaine use on their child's cognitive development.[135][136]

Motor development can be impaired by maternal cocaine use.[137][138] As is the case for cognitive and physical development, there are also studies showing no effect of cocaine use on motor development.[129][132]

Other

The use of cocaine by pregnant women is not the only drug that can have a negative effect on the fetus. Tobacco, marijuana, and opiates are also the types of drugs that can affect an unborn child's cognitive and behavioral development. Smoking tobacco increases pregnancy complications including low birth rate, prematurity, placental abruption, and intrauterine death. It can also cause disturbed maternal-infant interaction; reduced IQ, ADHD, and it can especially cause tobacco use in the child. Parental marijuana exposure may have long-term emotional and behavioral consequences. A ten-year-old child who had been exposed to the drug during pregnancy reported more depressive symptoms than fetuses unexposed. Some short-term effects include executive function impairment, reading difficulty, and delayed state regulation. An opiate drug, such as heroin, decreases birth weight, birth length, and head circumference when exposed to the fetus. Parental opiate exposure has greater conflicting impact than parental cocaine exposure on the infant's Central Nervous System and autonomic nervous system. There are also some negative consequences on a child that you wouldn't think of with opiates, such as: less rhythmic swallowing, strabismus, and feelings of rejection.[139]

Malnutrition and Undernutrition