Bilaminar embryonic disc

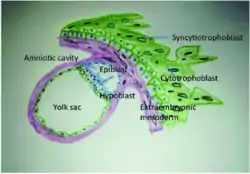

The bilaminar embryonic disc, bilaminar blastoderm or embryonic disc is the two-layered structure of epiblast and hypoblast, differentiated from the inner cell mass also known as the embryoblast.[1][2][3] These two layers of cells lie between two cavities: the primitive yolk sac and the amniotic cavity.

| Bilaminar embryonic disc | |

|---|---|

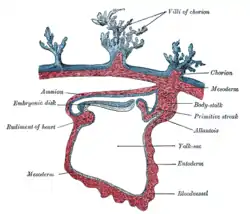

Section through the embryo. (Bilaminar disc is labeled as embryonic disk.) | |

Embryonic disc at implantation site with epiblast expanded to form the amniotic cavity | |

| Details | |

| Days | 13 |

| Precursor | Inner cell mass |

| Identifiers | |

| TE | embryonic disc_by_E6.0.1.1.3.0.1 E6.0.1.1.3.0.1 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The inner cell mass, begins to transform into two distinct epithelial layers just before implantation is completed. The epiblast, also known as the primitive ectoderm, is the outer layer that consists of columnar cells. The inner layer is called the hypoblast, also known as the primitive endoderm, which is composed of cuboidal cells. As the two layers become evident, a basement membrane presents itself between the layers. The final two layers of the embryoblast are known collectively as the bilaminar embryonic disc. This bilaminar disc also defines the primitive dorsal ventral axis.[2] Blastocyst implantation will occur during the second week of embryonic development in the endometrium of the uterus;[4] the epiblast is dorsal and the hypoblast is ventral.[2]

Formation

The zygote undergoes cleavage as it journeys from the fallopian tube to the uterus. As it transforms from 2 to 4, to 8 to 16 cells, it becomes a ball of cells called a morula. During these divisions, the zygote remains the same size, but the number of cells increases. The morula differentiates into an outer and inner group of cells: the peripheral outer cell layer, the trophoblast, and the central inner cell mass, the embryoblast. The trophoblast goes on to become the fetal portion of the placenta and related fetal membranes. The epiblast and hypoblast arise from the embryoblast and later give rise to the embryo proper and its affiliated fetal membranes. Once the zygote has differentiated into 16-32 cells, it starts to form a fluid-filled central cavity called the blastocyst cavity called the blastocoel.[5] This cavity is essential because as the cells continue to divide, the outer layer of cells increases making it difficult for the innermost cells to receiving adequate nutrients from the surrounding fluid. Therefore, the blastocyst cavity serves as a nutrient center and the fluid is able to reach and feed cells so that they can continue growing and dividing.[4] The embryo is called a blastocyst at about the 6th day of development once it has reached nearly 100 cells. Once formed, the blastocyst begins its journey into the uterus to start implantation in the endometrium.[5] During implantation the inner cell mass differentiates into two layers the epiblast, and the hypoblast which are the two layers of the bilaminar embryonic disc. The epiblast gives rise to the embryo proper, and the hypoblast gives rise to the fetal membranes.

Establishment of the amniotic cavity

Beginning on day 8, the amniotic cavity is the first new cavity to form during the second week of development.[5] Fluid collects between the epiblast and the hypoblast, which splits the epiblast into two portions. The layer at the embryonic pole grows around the amniotic cavity, creating a barrier from the cytotrophoblast. This becomes known as the amnion, which is one of the four extraembyonic membranes and the cells it comprises are referred to as amnioblasts.[6] Although, the amniotic cavity starts off small it eventually grows to be larger than the blastocyst and by week 8, the whole embryo is encompassed by the amnion.[5]

Formation of the yolk sac and chorionic cavity

The formation of the chorionic cavity (extraembryonic coelom) and the yolk sac (umbilical vesicle) is still debated. The thought of how the yolk sac membranes are formed begins with an increase in production of hypoblast cells, succeeded by different patterns of migration. On day 8, the first portion of hypoblast cells begin their migration and make what is known as the primary yolk sac, or Heuser's membrane (exocoelomic membrane). By day 12, the primary yolk sac has been disestablished by a new batch of migrating hypoblast cells that now contribute to the definitive yolk sac.[5]

While the primary yolk sac is forming, extraembryonic mesoderm makes its way into the blastocyst cavity to fill it with loosely packed cells. When the extraembryonic mesoderm is separated into two portions, a new gap arises called the chorionic cavity, or the extra-embryonic coelom. This new cavity is responsible for detaching the embryo and its amnion and yolk sac from the far wall of the blastocyst, which is now named the chorion. When the extraembryonic mesoderm splits into two layers, the amnion, yolk sac, and chorion follow its lead and also become double layered. The chorion and amnion are composed of extraembryonic ectoderm and mesoderm, where as the yolk sac is made of extraembryonic endoderm and mesoderm. When day 13 rolls around, the connecting stalk, a dense portion of extraembryonic mesoderm, restrains the embryonic disc in the chorionic cavity.[5]

Yolk sac during development

Like the amnion, the yolk sac is an extraembryonic membrane that surrounds a cavity. Formation of the definitive yolk sac happens after the extraembryonic mesoderm splits, and it becomes a double layered structure with hypoblast-derived endoderm on the inside and mesoderm surrounding the outside. The definitive yolk sac contributes greatly to the embryo during the 4th week of development, and executes critical functions for the embryo. One of which being the formation of blood, or hematopoiesis. Also, primordial germ cells are first found in the wall of the yolk sac. After the 4th week of development, the growing embryonic disc becomes a great deal larger than the yolk sac and its presence usually dies out before birth. However, the yolk sac may rarely remain as a deviation of the digestive tract named Meckel's diverticulum.[5]

Epiblast cells during gastrulation

The third week of development and the formation of the primitive streak sparks the beginning of gastrulation.[5] Gastrulation is when the three germ cell layers develop as well as an organism’s body plan.[7] During gastrulation, cells of the epiblast, a layer of the bilaminar blastocyst, migrate towards the primitive streak, enter it, and then move apart from it through a process called ingression.[5]

Definitive endoderm development

On day 16, epiblast cells that are next to the primitive streak experience epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation as they ingress through the primitive streak. The first wave of epiblast cells takes over the hypoblast, which slowly becomes replaced by new cells that eventually constitute the definitive endoderm. The definitive endoderm is what makes the lining of the gut and other associated gut structures.[5]

Intraembryonic mesoderm development

Also beginning on day 16, some of the ingressing epiblast cells make their way into the area between the epiblast and the newly forming definitive endoderm. This layer of cells becomes known as intraembryonic mesoderm. After the cells have moved bilaterally from the primitive streak and matured, four divisions of intraembryonic mesoderm are made; cardiogenic mesoderm, paraxial mesoderm, intermediate mesoderm and lateral plate mesoderm.[5]

Ectoderm development

After the definitive endoderm and intraembryonic mesoderm formations are complete, the remaining epiblast cells do not ingress through the primitive streak; rather they remain on the outside and form the ectoderm. It is not long until the ectoderm becomes the neural plate and surface ectoderm. Due to the fact that an embryo develops cranial to caudal, the formation of ectoderm does not happen at the same rate during development. The more inferior portion of the primitive streak will still have epiblast cells ingressing to make intraembryonic mesoderm, while the more superior portion has stop ingressing. However, eventually gastrulation finishes and the three germ layers are complete.[5]

References

- Sadler, T. W. (2010). Langman's medical embryology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins. p. 54. ISBN 9780781790697.

- Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2015). Larsen's human embryology (Fifth ed.). Philadelphia, PA. p. 47. ISBN 9781455706846.

- "27.3B: Bilaminar Embryonic Disc Development". Medicine LibreTexts. 24 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- "Bilaminar Embryonic Disc." Atlas of Human Embryology. Chronolab A.G. Switzerland, n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. <http://www.embryo.chronolab.com/formation.htm Archived 2012-11-19 at the Wayback Machine>.

- Schoenwolf, Gary C., and William J. Larsen. Larsen's Human Embryology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2009. Print.

- "10.1 Early Development and Implantation." The Embryoblast. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2012. <http://www.embryology.ch/anglais/fplacenta/fecond04.html>

- "Home". gastrulation.org.