Epidemiology of domestic violence

Domestic violence occurs across the world, in various cultures,[1] and affects people across society, at all levels of economic status;[2] however, indicators of lower socioeconomic status (such as unemployment and low income) have been shown to be risk factors for higher levels of domestic violence in several studies.[3] In the United States, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 1995, women reported a six times greater rate of intimate partner violence than men.[4][5] However, studies have found that men are much less likely to report victimization in these situations.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Killing |

|

| Sexual assault and rape |

|

| Disfigurement |

|

| Other issues |

|

| International legal framework |

|

| Related topics |

|

While some sources state that gay and lesbian couples experience domestic violence at the same frequency as heterosexual couples,[7] other sources report that domestic violence rates among gay, lesbian and bisexual people might be higher but more under-reported.[8]

By demographic

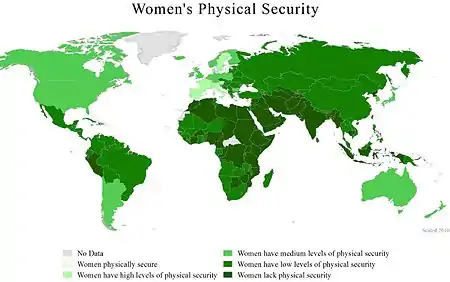

Against women

According to various national surveys, the percentage of women who were ever physically assaulted by an intimate partner varies substantially by country: Barbados (30%), Canada (29%), Egypt (34%), New Zealand (35%), Switzerland (21%), United States (33%).[9][10] Some surveys in specific places report figures as high as 50–70% of women who were ever physically assaulted by an intimate partner.[9] Others, including surveys in the Philippines and Paraguay, report figures as low as 10%.[9]

Statistics published in 2004 show that the rate of domestic violence victimisation for Indigenous women in Australia may be 40 times the rate for non-Indigenous women.[11]

80% of women surveyed in rural Egypt said that beatings were common and often justified, particularly if the woman refused to have sex with her husband.[12] Up to two-thirds of women in certain communities in Nigeria's Lagos State say they are victims to domestic violence.[13]

In Turkey 42% of women over 15 have suffered physical or sexual violence.[14] In India, around 70% of women are victims of domestic violence.[15][16]

Between 1993 and 2001, U.S. women reported intimate partner violence almost seven times more frequently than men (a ratio of 20:3).[17] Statistics for the year 1994 showed that more than five times as many females reported being victimized by an intimate than did males.[18]

Pregnancy

Domestic violence during pregnancy can be missed by medical professionals because it often presents in non-specific ways. A number of countries have been statistically analyzed to calculate the prevalence of this phenomenon:

- UK prevalence: 3.4%[19]

- USA prevalence: 3.2–33.7%[20][21]

- Ireland prevalence: 12.5%[22]

- Rates are higher in teenagers[23]

- Severity and frequency increase postpartum (10% antenatally vs. 19% postnatally);[24] 21% at three months post partum[25]

There are a number of presentations that can be related to domestic violence during pregnancy: delay in seeking care for injuries; late booking, non-attenders at appointments, self-discharge; frequent attendance, vague problems; aggressive or over-solicitous partner; burns, pain, tenderness, injuries; vaginal tears, bleeding, STDs; and miscarriage.

Domestic violence against a pregnant woman can also affect the fetus and can have lingering effects on the child after birth. Physical abuse is associated with neonatal death (1.5% versus 0.2%), and verbal abuse is associated with low birth weight (7.6% versus 5.1%).[26]

Against men

Due to social stigmas regarding male victimization, men who are victims of domestic violence face an increased likelihood of being overlooked by healthcare providers.[27][28][29][30] While much attention has been focused on domestic violence against women, researchers showed that also domestic violence that men experience from other men needs also attention.[5] The issue of victimization of men by women has been contentious, due in part to studies which report drastically different statistics regarding domestic violence.

Severe perpetration of physical violence tends to be committed by men,[31][32] and victimization reports generally show women being more likely to experience domestic violence than men.[33] A 2013 review of the literature that combined perpetration and victimization reports indicate that, worldwide, most studies only look at female victimization. The review examined studies from five continents and the correlation between a country's level of gender inequality and rates of domestic violence. The authors found that when partner abuse is defined broadly to include emotional abuse, any kind of hitting, and who hits first, partner abuse is relatively even. They also stated if one examines who is physically harmed and how seriously, expresses more fear, and experiences subsequent psychological problems, domestic violence is significantly gendered toward women as victims.[34]

Sherry Hamby argues that victimization reports are more reliable than perpetration reports and therefore studies showing women being more likely to suffer domestic violence than men are the accurate ones.[35] A 2016 meta-analysis indicated that the only risk factors for the perpetration of intimate partner violence that differ by gender are witnessing intimate partner violence as a child, alcohol use, male demand, and female withdrawal communication patterns.[36]

Among LGBT people

Some sources state that gay and lesbian couples experience domestic violence at the same frequency as heterosexual couples,[7] while other sources state domestic violence among gay and lesbian couples might be higher than among heterosexual couples, that gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals are less likely to report domestic violence that has occurred in their intimate relationships than heterosexual couples are, or that lesbian couples experience domestic violence less than heterosexual couples do.[8] By contrast, some researchers commonly assume that lesbian couples experience domestic violence at the same rate as heterosexual couples, and have been more cautious when reporting domestic violence among gay male couples.[37] In a survey by the Canadian Government, some 19% of lesbian women reported being victimized by their partners.[38] Other research reports that lesbian relationships exhibit substantially higher rates of physical aggression.[39]

Against children

The U.S Department of Health and Human Services reports that for each year between 2000 and 2005, "female parents acting alone" were most common perpetrators of child abuse.[40]

When it comes to domestic violence towards children involving physical abuse, research in the UK by the NSPCC indicated that "most violence occurred at home" (78%). Forty to sixty percent of men and women who abuse other adults also abuse their children.[41] Girls whose fathers batter their mothers are 6.5 times more likely to be sexually abused by their fathers than are girls from non-violent homes.[42] In China in 1989, 39,000 baby girls died during their first year of life because they did not receive the same medical care that would be given to a male child.[16]

In Asia alone, about one million children working in the sex trade are held in slavery-like conditions.[16]

Between teenagers

Teen dating violence is a pattern of controlling behavior by one teenager over another teenager in the context of a dating relationship. While there are many similarities to "traditional" domestic violence, there are also some differences. Teens are much more likely than adults to become isolated from their peers as a result of controlling behavior by their romantic partner. Also, for many teens the abusive relationship may be their first dating experience, and so they may lack a "normal" dating experience with which to compare it. While teenagers are trying to establish their sexual identities, they are also confronting violence in their relationships and exposure to technology. Studies document that teenagers are experiencing significant amounts of dating or domestic violence. Depending on the population studied and the way dating violence is defined, between 9 and 35% of teens have experienced domestic violence in a dating relationship. When a broader definition of abuse that encompasses physical, sexual, and emotional abuse is used, one in three teen girls is subjected to dating abuse."[43]

Additionally, a significant number of teens are victims of stalking by intimate partners. Although involvement with romantic relationships is a critical aspect of adolescence, these relationships also present serious risks for teenagers. Unfortunately, adolescents in dating relationships are at greater risk of intimate partner violence than any other age group. Approximately one-third of adolescent girls are victims of physical, emotional, or verbal abuse from a dating partner. Estimates of sexual victimization range from 14% to 43% of girls and 0.3% to 36% for boys. According to the Center for Disease Control, in 2009, nearly 10% of students nationwide had been intentionally hit, slapped, or physically hurt by their boyfriend or girlfriend. Twenty-six percent of girls in a relationship reported being threatened with violence or experiencing verbal abuse; 13% reported being physically hurt or hit.[43]

Measuring

Measures of the incidence of violence in intimate relationships can differ markedly in their findings depending on the measures used. Care is needed when using domestic violence statistics to ensure that both gender bias and under-reporting issues do not affect the inferences that are drawn from the statistics.

Some researchers, such as Michael P. Johnson, suggest that where and how domestic violence is measured also affects findings, and caution is needed to ensure statistics drawn from one class of situations are not applied to another class of situations in a way that might have fatal consequences.[44] Other researchers, such as David Murray Fergusson, counter that domestic violence prevention services, and statistics that they produce, target the extreme end of domestic violence and preventing child abuse rather than domestic violence between couples.[45]

Europe

A 1992 Council of Europe study on domestic violence against women found that one in four women experience domestic violence over their lifetimes and between 6 and 10% of women suffer domestic violence in a given year.

In the European Union, DV is a serious problem in the Baltic States. These three countries – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – have also lagged behind most post-communist countries in their response to DV.[46] The problem in these countries is severe, and in 2013 a DV victim won a European Court of Human Rights case against Lithuania.[47][48]

United Kingdom

The British Crime Survey for 2006–2007 reported that 0.5% of people (0.6% of women and 0.3% of men) reported being victims of domestic violence during that year and 44.3% of domestic violence was reported to the police. According to the survey, 312,000 women and 93,000 men were victims of domestic violence.[49]

The Northern Ireland Crime Survey for 2005 reported that 13% of people (16% of women and 10% of men) reported being victims of domestic violence at some point in their lives.[50]

The National Study of Domestic Abuse for 2005 reported that 213,000 women and 88,000 men reported being victims of domestic violence at some point in their lives. According to the study, one in seven women and one in sixteen men were victims of severe physical abuse, severe emotional abuse, or sexual abuse.[5]

In the United Kingdom, the police estimate that around 35% of domestic violence against women is actually reported. A 2002 Women's Aid study found that 74% of separated women suffered from post-separation violence.

Canada

In Canada, the Assembly of First Nations evaluation of the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program conducted by CIET offers an inclusive and relatively unbiased national estimate. It documented domestic violence in a random sample of 85 First Nations across Canada: 22% (523 of 2,359) of mothers reported suffering abuse in the year prior to being interviewed; of these, 59% reported physical abuse.[51]

Results of studies which estimate the prevalence of domestic violence vary significantly, depending on specific wording of survey questions, how the survey is conducted, the definition of abuse or domestic violence used, the willingness or unwillingness of victims to admit that they have been abused and other factors. For instance, Straus (2005) conducted a study which estimated that the rate of minor assaults by women in the United States was 78 per 1,000 couples, compared with a rate for men of 72 per 1,000 and the severe assault rate was 46 per 1,000 couples for assaults by women and 50 per 1,000 for assaults by men. Neither difference is statistically significant. He claimed that since these rates were based exclusively on information provided by women respondents, the near-equality in assault rates could not be attributed to a gender bias in reporting.[52]

One analysis found that "women are as physically aggressive or more aggressive than men in their relationships with their spouses or male partners".[5] However, studies have shown that women are more likely to be injured. Archer's meta-analysis[53] found that women in the United States suffer 65% of domestic violence injuries. A Canadian study showed that 7% of women and 6% of men were abused by their current or former partners, but female victims of spousal violence were more than twice as likely to be injured as male victims, three times more likely to fear for their life, twice as likely to be stalked, and twice as likely to experience more than ten incidents of violence.[54] However, Straus notes that Canadian studies on domestic violence have simply excluded questions that ask men about being victimized by their wives.[52]

According to a 2004 survey in Canada, the percentages of males being physically or sexually victimized by their partners was 6% versus 7% for women. However, females reported higher levels of repeated violence and were more likely than men to experience serious injuries; 23% of females versus 15% of males were faced with the most serious forms of violence including being beaten, choked, or threatened with or having a gun or knife used against them. Also, 21% of women versus 11% of men were likely to report experiencing more than 10 violent incidents. Women who often experience higher levels of physical or sexual violence from their current partner were 44%, compared with 18% of men to suffer from an injury. Cases in which women are faced with extremely abusive partners result in the females having to fear for their lives due to the violence. In addition, statistics show that 34% of women feared for their lives, and 10% of men feared for theirs.[55]

Some studies show that lesbian relationships have similar levels of violence as heterosexual relationships.[56]

United States

Approximately 1.3 million women and 835,000 men report being physically assaulted by an intimate partner annually in the United States.[57] In the United States, domestic violence is the leading cause of injury to women between the ages of 15 and 44.[58]

Victims of DV are offered legal remedies, which include the criminal law, as well as obtaining a protection order. The remedies offered can be both of a civil nature (civil orders of protection and other protective services) and of a criminal nature (charging the perpetrator with a criminal offense). People perpetrating DV are subject to criminal prosecution, most often under assault and battery laws.[59]

Russia

In Russia, according to a representative of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, one in four families experiences domestic violence.[60] Domestic violence is not a specific criminal offense: it can be charged under various crimes of the criminal code (e.g. assault), but in practice cases of domestic violence turn into criminal cases only when they involve severe injuries, or the victim has died.[61] For more details see Domestic violence in Russia.

Asia

In Turkey 42% of women over 15 have suffered physical or sexual violence.[62]

Fighting the prevalence of domestic violence in Kashmir has brought Hindu and Muslim activists together.[63] According to some Islamic clerics and women's advocates, women from Muslim-majority cultures often face extra pressure to submit to domestic violence, as their husbands may manipulate Islamic law to exert their control.[64]

One study found that half of Palestinian women have been the victims of domestic violence.[65]

A study on Bedouin women in Israel found that most have experienced DV, most accepted it as a decree from God, and most believed they were to blame themselves for the violence. The study also showed that the majority of women were not aware of existing laws and policies which protect them: 60% said they did not know what a restraining order was.[66]

In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".[67]

In Jordan, part of article 340 of the Penal Code states that "he who discovers his wife or one of his female relatives committing adultery and kills, wounds, or injures one of them, is exempted from any penalty."[68] This has twice been put forward for cancellation by the government, but was retained by the Lower House of the Parliament, in 2003: a year in which at least seven honor killings took place.[69] Article 98 of the Penal Code is often cited alongside Article 340 in cases of honor killings. "Article 98 stipulates that a reduced sentence is applied to a person who kills another person in a 'fit of fury'".[70]

The Human Rights Watch found that up to 90% of women in Pakistan were subject to some form of maltreatment within their own homes.[71] Honor killings in Pakistan are a very serious problem, especially in northern Pakistan.[72][73] In Pakistan, honour killings are known locally as karo-kari. Karo-kari is a compound word literally meaning "black male" (Karo) and "black female" (Kari).

Domestic violence in India is widespread, and is often related to the custom of dowry.[74] Honor killings are more common in some regions of India, particularly in northern regions of the country. Honor killings have been reported in the states of Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar, as a result of people marrying without their family's acceptance, and sometimes for marrying outside their caste or religion.[75][76]

Africa

A UN report compiled from a number of different studies conducted in at least 71 countries found domestic violence against women to be most prevalent in Ethiopia.[77]

Up to two-thirds of women in certain communities in Nigeria's Lagos State say they are victims to domestic violence.[78]

80% of women surveyed in rural Egypt said that beatings were common and often justified, particularly if the woman refused to have sex with her husband.[12]

Australia

Statistics published in 2004, show that the rate of domestic violence victimisation for Indigenous women in Australia may be 40 times the rate for non-Indigenous women.[79]

Findings from the 2006 Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey show that among the female victims of physical assault, 31% were assaulted by a current or previous partner. Among male victims, 4.4% were assaulted by a current or previous partner. Thirty percent of people who had experienced violence by a current partner since the age of 15 were male, and seventy percent were female.[80]

References

- Watts C, Zimmerman C (April 2002). "Violence against women: global scope and magnitude". Lancet. 359 (9313): 1232–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. PMID 11955557. S2CID 38436965.

- Waits, Kathleen (1984–1985). "The Criminal Justice System's Response to Battering: Understanding the Problem, Forging the Solutions". Washington Law Review. 60: 267–330.

- Capaldi, Deborah; et al. (April 2012). "A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence". Partner Abuse. 3 (2): 231–280. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. PMC 3384540. PMID 22754606.

- Bachman, Ronet; Linda E. Saltzman (August 1995). "Violence against Women: Estimates from the Redesigned Survey" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived from the original (PDFNCJ 154348) on July 26, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|format= - "References Examining Assaults By Women On Their Spouses Or Male Partners: An Annotated Bibliography". Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- Tonia L. Nicholls; Hamel, John (2007). Family interventions in domestic violence: a handbook of gender-inclusive theory and treatment. New York: Springer Pub. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-8261-0245-4.

- Andrew Karmen (2010). Crime Victims: An Introduction to Victimology. Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 978-0495599296. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- Robert L. Hampton, Thomas P. Gullotta (2010). Interpersonal Violence in the African-American Community: Evidence-Based Prevention and Treatment Practices. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 49. ISBN 978-0387295985. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - "Ending Violence Against Women—Population Reports" (PDF). Series L, Number 11. Center for Health and Gender Equity (CHANGE). December 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Domestic Violence in Australia—an Overview of the Issues Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Parliamentary Library.

- Widespread violence against women in Africa documented Archived December 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Source: UNFPA.

- Half of Nigeria's women experience domestic violence. afrol News.

- "Behind the veil". The Economist. May 12, 2011.

- India tackles domestic violence. BBC News. October 26, 2006.

- Kristof, Nicholas D.; WuDunn, Sheryl (August 17, 2009). "The Women's Crusade". The New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- Rennison, Callie Marie (February 2003). "Intimate Partner Violence, 1993–2001" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived from the original (PDFNCJ 197838) on July 26, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); External link in|format= - Bureau of Justice Statistics, Sex Differences in Violent Victimization, 1994 Archived July 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, September 1997, NCJ-164508.

- Bacchus, Lorraine; Mezey, Gill; Bewley, Susan; Haworth, Alison (May 2004). "Prevalence of Domestic Violence When Midwives Routinely Enquire in Pregnancy". BJOG. 111 (5): 441–5. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00108.x. PMID 15104607. S2CID 23716418.

- Huth-Bocks, A. C.; Levendosky, A. A.; Bogat, G. A. (April 2002). "The Effects of Domestic Violence During Pregnancy on Maternal and Infant Health". Violence & Victims. 17 (2): 169–85. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.2.169.33647. PMID 12033553. S2CID 24217972.

- Torres, Sara; Campbell, Jacquelyn; Campbell, Doris W.; et al. (2000). "Abuse During and Before Pregnancy: Prevalence and Cultural Correlates". Violence & Victims. 15 (3): 303–21. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.15.3.303. PMID 11200104. S2CID 41026527.

- O'Donnell S.; Fitzpatrick M.; McKenna P. (November 2000). "Abuse in Pregnancy – The Experience of Women". Irish Medical Journal. 93 (8): 229–30. PMID 11133053.

- Parker, Barbara; McFarlane, Judith; Soeken, Karen; Torres, Sarah; Campbell, Doris (1993). "Physical and Emotional Abuse in Pregnancy: A Comparison of Adult and Teenage Women". Nursing Research. 42 (3): 173–8. doi:10.1097/00006199-199305000-00009. PMID 8506167. S2CID 33380396.

- Gielen, Andrea Carlson; O'Campo, Patricia J.; Faden, Ruth R.; Kass, Nancy E.; Xue, Xiaonan (September 1994). "Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year". Social Science and Medicine. 39 (6): 781–87. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90039-6. PMID 7802853.

- Harrykissoon, Samantha D.; Rickert, Vaughn I.; Wiemann, Constance M. (April 2002). "Prevalence and Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence Among Adolescent Mothers During the Postpartum Period". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 156 (4): 325–30. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.4.325. PMID 11929364.

- Yost, Nicole P.; Bloom, Steven L.; McIntire, Donald D.; Leveno, Kenneth J. (July 2005). "A Prospective Observational Study of Domestic Violence During Pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 106 (1): 61–65. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000164468.06070.2a. PMID 15994618. S2CID 35316404.

- Riviello, Ralph (July 1, 2009). Manual of Forensic Emergency Medicine. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 129. ISBN 978-0763744625. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017.

- Finley, Laura (July 16, 2013). Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence and Abuse. ABC-CLIO. p. 163. ISBN 978-1610690010. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017.

- Hess, Kären; Orthmann, Christine; Cho, Henry (January 1, 2016). Criminal Investigation. Cengage Learning. p. 323. ISBN 978-1435469938. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017.

- In D.R. Loseke, R.J. Gelles & M.M. Cavanaugh (Eds.), Current controversies on family violence (2nd edition, pp. 55–77). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Chan, Ko Ling (March–April 2011). "Gender differences in self-reports of intimate partner violence: a review". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 16 (2): 167–175. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2011.02.008. hdl:10722/134467. Pdf.

- Nadal KL (2017). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Psychology and Gender. SAGE Publications. p. 1297. ISBN 978-1483384276.

Research has indicated that females and males engage in comparable rates of physical aggression within intimate relationships, though the severity of the violence appears to be moderated by sex. Men tend to perpetrate more severe forms of violence against their partners; however, less severe violence (i.e., that which does not warrant medical attention) is often reciprocal and committed at equivalent rates.

- Desmarais, Sara L. Reeves, Kim A. Nicholls, Tonia L. Telford, Robin P. Fiebert, Martin S. "Prevalence of Physical Violence in Intimate Relationships, Part 1: Rates of Male and Female Victimization." Partner Abuse, Volume 3, Number 2, 2012. DOI: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.140

- Esquivel-Santovena, Esteban Eugenio; Lambert, Teri; Hamel, John (January 2013). "Partner abuse worldwide" (PDF). Partner Abuse. 4 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1891/1946-6560.4.1.e14.

- Hamby, Sherry. "A Scientific Answer to a Scientific Question: The Gender Debate on Intimate Partner Violence." July 2015 Trauma Violence & Abuse 18(2)DOI: 10.1177/1524838015596963

- "Gender Differences in Risk Markers for Perpetration of Physical. Partner Violence: Results from a Meta-Analytic Review." by Spencer et al. J Fam Viol (2016) 31:981–984 DOI 10.1007/s10896-016-9860-9.

- Bonnie S. Fisher, Steven P. Lab (2010). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society, Volume 1. SAGE. p. 312. ISBN 978-1412960472. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Canadian Government—Abuse in Lesbian Relationships

- "[A 1991 study] reported, in a survey of 350 lesbians, that rates of verbal, physical and sexual abuse were all significantly higher in lesbian relationships than in heterosexual relationships: 56.8% had been sexually victimized by a female, 45% had experienced physical aggression, and 64.5% experienced physical or emotional aggression. Of this sample of women, 78.2% had been in a prior relationship with a man. Reports of violence by men were all lower than reports of violence in prior relationships with women (sexual victimization, 41.9% (vs. 56.8% with women); physical victimization 32.4% (vs. 45%) and emotional victimization 55.1% (vs. 64.5%)." Dutton, 1994

- Stats for 2000 "Figure 4-2 Percentage of Victims by Type of Perpetrator, 2000 (DCDC, Child File)". Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2010.; for 2001 "Figure 4-4 Victims by Parental Status of Perpetrator, 2001 (Child File)". Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010.; for 2002 "Figure 3-6 Victims by Parental Status of Perpetrator, 2002". Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2010. for 2003 "Figure 4-2 Percentage of Victims by Type of Perpetrator, 2000 (DCDC, Child File)". Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2010.; for 2004 "Child Maltreatment 2004 : Figure 3-6 Victims by Perpetrator Relationship, 2004". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2010. for 2005 Archived March 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- American Psychological Association. Violence and the Family: Report of the American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Violence and the Family. 1996

- Bowker LH, Arbitell M, Mcferron JR (1988). "On the Relationship Between Wife Beating and Child Abuse". In Bograd ML, Yllö K (eds.). Feminist perspectives on wife abuse. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-8039-3053-4.

- King-Ries, Andrew (2011). "Teens, Technology, and Cyberstalking: The Domestic Violence Wave of the Future?". Texas Journal of Women and the Law. 20: 131–164.

- New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Katalin Fabian. "Mobilizing against Domestic Violence in Postcommunist Europe: Successes and Continuing Challenges | European Conference on Politics and Gender". Ecpg-barcelona.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Domestic violence victim wins European Court of Human Rights case against Lithuania | en.15min.lt". 15min.lt. May 30, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Lithuania – EU Court Judgment – Failure to Investigate Domestic Violence". Wunrn.com. March 28, 2013. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- Crime in England and Wales 2006/07 Archived November 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Andersson N, Nahwegahbow A (2010). "Family violence and the need for prevention research in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities. Pimatisiwin". Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 8 (2): 9–33. PMC 2962655. PMID 20975851.

- Straus, 2005

- Archer, J. (2000). "Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 126 (5): 651–680. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. PMID 10989615.

- "CBC News – Canada – Domestic violence rate unchanged, Statistics Canada finds". Cbc.ca. July 14, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- O'Grady William (2011). Crime in Canadian Context: debates and controversies. Oxford University Press ISBN 0195433785.

- Fact Sheet: Lesbian Partner Violence. Musc.edu. Retrieved on 2011-12-23.

- "Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey | National Institute of Justice". Ojp.usdoj.gov. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Domestic Violence: Fast Facts on Domestic Violence". Clarkprosecutor.org. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Protecting Victims of Domestic Violence (U.S.)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice / International Association of Chiefs of Police. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- "VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION" (PDF). ANNA National Centre for the Prevention of Violence.

- "BBC News – The silent nightmare of domestic violence in Russia". bbc.co.uk. March 1, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Behind the veil". The Economist. May 12, 2011.

- "Independent Appeal: Safe haven for women beaten and abused in Kashmir". The Independent. December 28, 2009.

- Constable, Pamela. "For Some Muslim Wives, Abuse Knows No Borders." The Washington Post (May 8, 2007).

- Alexander, Doug. "Addressing Violence Against Palestinian Women". Archived November 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine International Development Research Centre (June 23, 2000).

- Khoury, Jack (April 30, 2012). "Study: Most Bedouin victims of domestic violence believe it's a 'decree from God' Israel News Broadcast". Haaretz. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Altstein, Howard; Simon, Rita James (2003). Global perspectives on social issues: marriage and divorce. Lexington, Mass: Lexington Books. p. 11. ISBN 0-7391-0588-4.

- "Jordan quashes 'honour crimes' law". Al Jazeera. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- "Jordan: Special Report on Honour Killings". Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- "PAKISTAN: Domestic violence endemic, but awareness slowly rising". IRIN UN. March 11, 2008.

- "BBC News – Pakistani women shot in 'honour killings'". bbc.co.uk. June 27, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- http://www.af.org.pk/pub_files/1366345831.pdf

- Ash, Lucy (July 16, 2003). "Programmes | Crossing Continents | India's dowry deaths". BBC News. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Honour killing: SC notice to Centre, Haryana and 6 other states". The Times of India. June 21, 2010. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- Chaitra Arjunpuri. "'Honour killings' bring dishonour to India – Features". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Africa | Ethiopian women are most abused". BBC News. October 11, 2006. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- "Half of Nigeria's women experience domestic violence". Afrol News.

- "Domestic Violence in Australia—an Overview of the Issues Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Parliamentary Library.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey

External links

- World Report on Violence Against Children, Secretary-General of the United Nations

- Hidden in Plain Sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children, UNICEF