Epididymis

The epididymis (/ɛpɪˈdɪdɪmɪs/; plural: epididymides /ɛpɪdɪˈdɪmədiːz/ or /ɛpɪˈdɪdəmɪdiːz/) is a tube that connects a testicle to a vas deferens in the male reproductive system. It is present in all male reptiles, birds, and mammals. It is a single, narrow, tightly-coiled tube in adult humans, 6 to 7 meters (20 to 23 ft) in length[1] connecting the efferent ducts from the rear of each testicle to its vas deferens.

| Epididymis | |

|---|---|

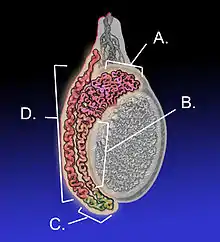

Adult human testicle with epididymis: A. Head of epididymis, B. Body of epididymis, C. Tail of epididymis, and D. Vas deferens | |

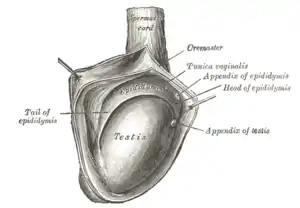

The right testis, exposed by laying open the tunica vaginalis. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Wolffian duct |

| Vein | Pampiniform plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Epididymis |

| MeSH | D004822 |

| TA98 | A09.3.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3603 |

| FMA | 18255 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

The epididymis can be divided into three main regions:

- The head (Latin: caput). The head of the epididymis receives spermatozoa via the efferent ducts of the mediastinium of the testis. It is characterized histologically by a thick epithelium with long stereocilia (described below) and a little smooth muscle.[2] It is involved in absorbing fluid to make the sperm more concentrated. The concentration of the sperm here is dilute.

- The body (Latin: corpus). This has an intermediate epithelium and smooth muscle thickness.[2]

- The tail (Latin: cauda). This has the thinnest epithelium of the three regions and the greatest quantity of smooth muscle.[2]

In reptiles, there is an additional canal between the testis and the head of the epididymis and which receives the various efferent ducts. This is, however, absent in all birds and mammals.[3]

Histology

The epididymis is covered by a two layered pseudostratified epithelium. The epithelium is separated by a basement membrane from the connective tissue wall which has smooth muscle cells. The major cell types in the epithelium are:

- Principal cells: columnar cells that, with the basal cells, form the majority of the epithelium. In the caput (head) region these cells have long stereocilia that are tuft-like extensions that project into the lumen.[4] The stereocilia are much shorter in the cauda (tail) segment.[4] They also secrete carnitine, sialic acid, glycoproteins, and glycerylphosphorylcholine into the lumen.

- Basal cells: shorter, pyramid-shaped cells which contact the basal lamina but taper off before their apical surfaces reach the lumen. These are thought to be undifferentiated precursors of principal cells.

- Apical cells: predominantly found in the head region

- Clear cells: predominant in the tail region

- Intraepithelial lymphocytes: distributed throughout the tissue.

- Intraepithelial macrophages[5][6]

Stereocilia

The stereocilia of the epididymis are long cytoplasmic projections that have an actin filament backbone.[4] These filaments have been visualized at high resolution using fluorescent phalloidin that binds to actin filaments.[4] The stereocilia in the epididymis are non-motile. These membrane extensions increase the surface area of the cell, allowing for greater absorption and secretion. It has been shown that epithelial sodium channel ENaC that allows the flow of Na+ ions into the cell is localized on stereocilia.[4]

Because sperm are initially non-motile as they leave the seminiferous tubules, large volumes of fluid are secreted to propel them to the epididymis. The core function of the stereocilia is to resorb 90% of this fluid as the spermatozoa start to become motile. This absorption creates a fluid current that moves the immobile sperm from the seminiferous tubules to the epididymis. Spermatozoa do not reach full motility until they reach the vagina, where the alkaline pH is neutralized by acidic vaginal fluids.

Development

In the embryo, the epididymis develops from tissue that once formed the mesonephros, a primitive kidney found in many aquatic vertebrates. Persistence of the cranial end of the mesonephric duct will leave behind a remnant called the appendix of the epididymis. In addition, some mesonephric tubules can persist as the paradidymis, a small body caudal to the efferent ductules.

A Gartner's duct is a homologous remnant in the female.

Function

Role in storage of sperm and ejaculant

Spermatozoa formed in the testis enter the caput epididymis, progress to the corpus, and finally reach the cauda region, where they are stored. Sperm entering the caput epididymis are incomplete—they lack the ability to swim forward (motility) and to fertilize an egg. Epididymal transit takes 2 to 6 days in humans and 10–13 in rodents.[7] During their transit in the epididymis, sperm undergo maturation processes necessary for them to acquire motility and fertility.[8] Final maturation (capacitation) is completed in the female reproductive tract.

The epididymis secretes immobilin, a large glycoprotein that is responsible for the creating of the viscoelastic luminal environment that serves to mechanically immobilize spermatozoa until ejaculation. Immobilin is predominantly secreted into the proximal caput epididymis prior to the acquisition of the potential for sperm motility.[9]

During emission, sperm flow from the cauda epididymis (which functions as a storage reservoir) into the vas deferens where they are propelled by the peristaltic action of muscle layers in the wall of the vas deferens, and are mixed with the diluting fluids of the prostate, seminal vesicles, and other accessory glands prior to ejaculation (forming semen).

Contrary to popular belief, sperm are capable of causing a pregnancy even without ever travelling through the epididymis.[10][11] This has been proven in two cases in the United States in the 1980s where a couple of men's vasa deferentia were directly surgically attached to their efferent ducts and these men both subsequently impregnated their partners within the next couple of years.[10] This has also been proven in a similar case in Western Europe in the early 1990s.[11]

Antioxidant defenses

During their transit through the epididymis, the spermatozoa undergo a series of transformations in preparation for their ultimate task of fertilizing the oocyte. In order to protect the spermatozoa during their transit through the epididymis, the epididymal epithelium produces a variety of antioxidant proteins that help protect the spermatozoa from oxidative damage[12]. The antioxidant proteins produced include catalase, glutathione peroxidases, glutathione-S-transferases, peroxiredoxins, superoxide dismutases, thioredoxin reductase and thioredoxins[12]. Deficiencies in the availability of these antioxidant proteins reduces sperm quality by affecting a variety of the proteins necessary for the motility needed to fertilize oocytes. Reduced antioxidant activity also causes increased oxidative damage to the sperm DNA[12].

Clinical significance

Inflammation

An inflammation of the epididymis is called epididymitis. It is much more common than testicular inflammation, termed orchitis.

Surgical removal

Epididymotomy is the placing of an incision into the epididymis and is sometimes considered as a treatment option for acute suppurating epididymitis. Epididymectomy is the surgical removal of the epididymis sometimes performed for post-vasectomy pain syndrome and for refractory cases of epididymitis.

Epididymectomy is also performed for sterilization on some male animals of livestock species so they can be used to detect estrus in females ready for artificially insemination.

Gallery

Human male reproductive system

Human male reproductive system Testis

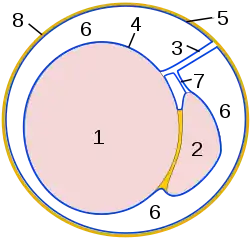

Testis Schematic drawing: cross-section through a testicle

Schematic drawing: cross-section through a testicle Micrograph of epididymis - H&E stain

Micrograph of epididymis - H&E stain Micrograph

Micrograph Deep dissection of epididymis

Deep dissection of epididymis

See also

- Epididymis evolution from reptiles to mammals

- Epididymal hypertension – Condition that arises during male sexual arousal when seminal fluid is not ejaculated

Notes

- Kim, Howard H.; Goldstein, Marc (2010). "Chapter 53: Anatomy of the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicle". In Graham, Sam D.; Keane, Thomas E.; Glenn, James F. (eds.). Glenn's urological surgery (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-7817-9141-0.

- Bacha, William; Bacha, Linda (2012). Color Atlas of Veterinary Histology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 226. ISBN 978-0470958513.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 394–395. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- Sharma S, Hanukoglu I (2019). "Mapping the sites of localization of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and CFTR in segments of the mammalian epididymis". Journal of Molecular Histology. 50 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1007/s10735-019-09813-3. PMID 30659401. S2CID 58026884.

- Da Silva N, Cortez-Retamozo V, Reinecker HC, et al. (May 2011). "A dense network of dendritic cells populates the murine epididymis". Reproduction. 141 (5): 653–63. doi:10.1530/REP-10-0493. PMC 3657760. PMID 21310816.

- Shum WW, Smith TB, Cortez-Retamozo V, et al. (May 2014). "Epithelial basal cells are distinct from dendritic cells and macrophages in the mouse epididymis". Biology of Reproduction. 90 (5): 90. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.113.116681. PMC 4076373. PMID 24648397.

- Cornwall, Gail A. (2009). "New insights into epididymal biology and function". Human Reproduction Update. 15 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmn055. ISSN 1355-4786. PMC 2639084. PMID 19136456.

- Jones RC (April 1999). "To store or mature spermatozoa? The primary role of the epididymis". International Journal of Andrology. 22 (2): 57–67. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00151.x. PMID 10194636.

- Zhou, Wei; De Iuliis, Geoffry N.; Dun, Matthew D.; Nixon, Brett (2018). "Characteristics of the Epididymal Luminal Environment Responsible for Sperm Maturation and Storage". Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9: 59. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00059. PMC 5835514. PMID 29541061.

- Silber, Sherman J. (1988). "Pregnancy caused by sperm from vasa efferentia". Fertility and Sterility. 49 (2): 373–375. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)59733-7. PMID 3338593.

- Weiske, W. H. (1994). "Pregnancy caused by sperm from vasa efferentia". Fertility and Sterility. 62 (3): 642–643. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56959-3. PMID 8062964.

- O'Flaherty C. Orchestrating the antioxidant defenses in the epididymis. Andrology. 2019 Sep;7(5):662-668. doi: 10.1111/andr.12630. Epub 2019 May 1. PMID: 31044545

External links

- Histology image: 16903loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University