Epigenetics of neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are a heterogeneous group of complex disorders linked by the degeneration of neurons in either the peripheral nervous system or the central nervous system. Their underlying causes are extremely variable and complicated by various genetic and/or environmental factors. These diseases cause progressive deterioration of the neuron resulting in decreased signal transduction and in some cases even neuronal death. Peripheral nervous system diseases may be further categorized by the type of nerve cell (motor, sensory, or both) affected by the disorder. Effective treatment of these diseases is often prevented by lack of understanding of the underlying molecular and genetic pathology. Epigenetic therapy is being investigated as a method of correcting the expression levels of misregulated genes in neurodegenerative diseases.

.gif)

Neurodengenerative diseases of motor neurons can cause degeneration of motor neurons involved in voluntary muscle control such as muscle contraction and relaxation. This article will cover the epigenetics and treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). See the Motor Neuron Fact Sheet for details regarding other motor neuron diseases. Neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system can affect the brain and/or spinal cord. This article will cover the epigenetics and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD). These diseases are characterized by chronic and progressive neuronal dysfunction, sometimes leading to behavioral abnormalities (as with PD), and, ultimately, neuronal death, resulting in dementia.

Neurodegenerative diseases of sensory neurons can cause degeneration of sensory neurons involved in transmitting sensory information such as hearing and seeing. The main group of sensory neuron diseases are hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies (HSAN) such as HSAN I, HSAN II, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 2B (CMT2B).[1][2] Though some sensory neuron diseases are recognized as neurodegenerative, epigenetic factors have not yet been clarified in the molecular pathology.

Epigenetics and epigenetic drugs

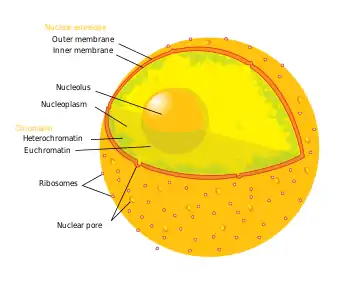

The term epigenetics refers to three levels of gene regulation: (1) DNA methylation, (2) histone modifications, and (3) non-coding RNA (ncRNA) function. Briefly, histone-mediated transcriptional control occurs by the wrapping of DNA around a histone core. This DNA-histone structure is called a nucleosome; the more tightly the DNA is bound by the nucleosome, and the more tightly a string of nucleosomes are compressed among each other, the greater the repressive effect on transcription of genes in the DNA sequences near or wrapped around the histones, and vice versa (i.e. looser DNA binding and relaxed compaction leads to a comparatively derepressed state, resulting in facultative heterochromatin or, even further derepressed, euchromatin). At its most repressive state, involving many folds into itself and other scaffolding proteins, DNA-histone structures form constitutive heterochromatin. This chromatin structure is mediated by these three levels of gene regulation. The most relevant epigenetic modifications to treatment of neurodegenerative diseases are DNA methylation and histone protein modifications via methylation or acetylation.[3][4]

- In mammals, methylation occurs on DNA and histone proteins. DNA methylation occurs on the cytosine of CpG dinucleotides in the genomic sequence, and protein methylation occurs on the amino termini of the core histone proteins - most commonly on lysine residues.[4] CpG refers to a dinucleotide composed of a cytosine deoxynucleotide immediately adjacent to a guanine deoxynucleotide. A cluster of CpG dinucleotides clustered together is called a CpG island, and in mammals, these CpG islands are one of the major classes of gene promoters, onto or around which transcription factors may bind and transcription can begin. Methylation of CpG dinucleotides and/or islands within gene promoters is associated with transcriptional repression via interference of transcription factor binding and recruitment of transcriptional repressors with methyl binding domains. Methylation of intragenic regions is associated with increased transcription. The group of enzymes responsible for addition of methyl groups to DNA are called DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). The enzyme responsible for removal of methyl group are called DNA demethylases. The effects of histone methylation are residue dependent (e.g. which amino acid on which histone tail is methylated) therefore the resulting transcriptional activity and chromatin regulation can vary.[4] The enzymes responsible for the addition of methyl groups to histones are called histone methyltransferases (HMTs). The enzymes responsible for the removal of methyl groups from histone are histone demethylases.

- Acetylation occurs on the lysine residues found at the amino N-terminal of histone tails. Histone acetylation is most commonly associated with relaxed chromatin, transcriptional derepression, and thus actively transcribed genes.[4] Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) are enzymes responsible for the addition of acetyl groups, and histone deacetylases (HDACs) are enzymes responsible for the removal of acetyl groups. Therefore, the addition or removal of an acetyl group to a histone can alter the expression of nearby genes. The majority of drugs being investigated are inhibitors of proteins that remove acetyl from histones or histone deacetylases (HDACs).

- Briefly, ncRNAs are involved in signaling cascades with epigenetic marking enzymes such as HMTs, and/or with RNA interference(RNAi) machinery. Frequently these signaling cascades result in epigenetic repression (for one example, see X-chromosome inactivation), though there are some cases in which the opposite is true. For example, BACE1-AS ncRNA expression is upregulated in Alzheimer's disease patients and results in increased stability of BACE1 - the mRNA precursor to an enzyme involved in Alzheimer's disease.[5]

Epigenetic drugs target the proteins responsible for modifications on DNA or histone. Current epigenetic drugs include but are not limited to: HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), HAT modulators, DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, and histone demethylase inhibitors.[6][7] The majority of epigenetic drugs tested for use against neurodegenerative diseases are HDAC inhibitors; however, some DNMT inhibitors have been tested as well. While the majority of epigenetic drug treatments have been conducted in mouse models, some experiments have been performed on human cells as well as in human drug trials (see table below). There are inherent risks in using epigenetic drugs as therapies for neurodegenerative disorders as some epigenetic drugs (e.g. HDACis such as sodium butyrate) are non-specific in their targets, which leaves potential for off-target epigenetic marks causing unwanted epigenetic modifications.

| Function | Classification | Drug | ALS | AD | HD | PD | SMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-methylation inhibitor | chemical analogue of cytidine | Azathioprine | M (ny) | M (ny) | |||

| HDAC inhibitor (small molecule) | benzamide | M344 | MC 19 | ||||

| fatty acid | Sodium butyrate | M (y) 5, 6, 7 ; H (ny) | D (y) 11 | M (y) 14; R (y) 15;

D (y) 16, 18; H (ny) |

MC 20; M (y) 21; H (ny) | ||

| Sodium phenylbutyrate | M (y) 1; H (y) 2 | M (y) 8; H (ny) | H (ys) 12 | MC 20; H (v) 21, 22 | |||

| Valproic acid | M (y) 2; H (ni) 3 | M (y) 9; H (ny) | D (y) 11 | R (y) 17; H (ny) | MC 23, 24; M (y) 25;

H (v) 26, 27, 28, 29 | ||

| hydroxamic acid | Trichostatin A | M (y) 4; H (ny) | M (y) 10; H (ny) | MC 13; D (y) 11 | M (y) 30, 31; H (ny) | ||

| Vorinostat (suberanilohydroxamic acid-SAHA) | M (y) 9; H (ny) | MC 13; D (y) 11 | D (y) 18 | MC 32, 33; M (y) 34; H (ny) |

- Disease: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington's disease (HD), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), Parkinson's disease (PD)

- Tested on: mouse (M), only mouse cells (MC), human (H), Drosophila (D), rat (R)

- Successful treatment: yes (y), yes but with side effects (ys), not yet (ny), variable (v), no improvement (ni)

- References: listed by column (disease) and by ascending row (drug) order

- ALS: (1)[8][9] (2)[10] (3)[11] (4)[12]

- AD: (5)[13] (6)[14] (7)[15] (8)[14] (9)[16] (10)[17]

- HD: (11)[18] (12)[19] (13)[20]

- PD: (14)[21] (15)[22] (16)[23] (17)[24] (18)[25]

- SMA: (19)[26] (20)[27] (21)[28] (22)[29] (23)[30] (24)[31] (25)[32] (26)[33] (27)[34] (28)[35] (29)[36] (30)[37] (31)[38] (32)[39] (33)[40] (34)[41]

Neurodegenerative diseases of motor neurons

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, is a motor neuron disease that involves neurogeneration. All skeletal muscles in the body are controlled by motor neurons that communicate signals from the brain to the muscle through a neuromuscular junction. When the motor neurons degenerate, the muscles no longer receive signals from the brain and begin to waste away. ALS is characterized by stiff muscles, muscle twitching, and progressive muscle weakness from muscle wasting. The parts of the body affected by early symptoms of ALS depend on which motor neurons in the body are damaged first, usually the limbs. As the disease progresses most patients are unable to walk or use their arms and eventually develop difficulty speaking, swallowing and breathing. Most patients retain cognitive function and sensory neurons are generally unaffected. Patients are often diagnosed after the age of 40 and the median survival time from onset to death is around 3–4 years. In the final stages, patients can lose voluntary control of eye muscles and often die of respiratory failure or pneumonia as a result of degeneration of the motor neurons and muscles required for breathing. Currently there is no cure for ALS, only treatments that may prolong life.

Genetics and underlying causes

To date, multiple genes and proteins have been implicated in ALS. One of the common themes between many of these genes and their causative mutations is the presence of protein aggregates in motor neurons.[42] Other common molecular features in ALS patients are altered RNA metabolism[43] and general histone hypoacetylation.[44]

- SOD1

- The SOD1 gene on chromosome 21 that codes for the superoxide dismutase protein is associated with 2% of cases and is believed to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner.[45] Many different mutations in SOD1 have been documented in ALS patients with varying degrees of progressiveness. SOD1 protein is responsible for destroying naturally occurring, but harmful superoxide radicals produced by the mitochondria. Most of the SOD1 mutations associated with ALS are gain-of-function mutations in which the protein retains its enzymatic activity, but aggregate in motor neurons causing toxicity.[46][47] Normal SOD protein is also implicated in other cases of ALS due to potentially cellular stress.[48] An ALS mouse model through gain-of-function mutations in SOD1 has been developed.[49]

- c9orf72

- A gene called c9orf72 was found to have a hexanucleotide repeat in the non-coding region of the gene in association with ALS and ALS-FTD.[50] These hexanucleotide repeats may be present in up 40% of familial ALS cases and 10% of sporadic cases. C9orf72 likely functions as a guanine exchange factor for a small GTPase, but this is likely not related to the underlying cause of ALS.[51] The hexanucleotide repeats are likely causing cellular toxicity after they are spliced out of the c9orf72 mRNA transcripts and accumulate in the nuclei of affected cells.[50]

- UBQLN2

- The UBQLN2 gene encodes the protein ubiquilin 2 which is responsible for controlling the degradation of ubiquitinated proteins in the cell. Mutations in UBQLN2 interfere with protein degradation resulting in neurodegeneration through abnormal protein aggregation.[52] This form of ALS is X chromosome-linked and dominantly inherited and can also be associated with dementia.

Epigenetic treatment with HDAC inhibitors

ALS patients and mouse models show general histone hypoacetylation that can ultimately trigger apoptosis of cells.[53] In experiments with mice, HDAC inhibitors counteract this hypoacetylation, reactivate aberrantly down-regulated genes, and counteract apoptosis initiation.[12][54] Furthermore, HDAC inhibitors are known to prevent SOD1 protein aggregates in vitro.[55]

- Sodium phenylbutyrate

- Sodium phenylbutyrate treatment in a SOD1 mouse model of ALS showed improved motor performance and coordination, decreased neural atrophy and neural loss, and increased weight gain.[8][9] Release of pro-apoptotic factors was also abrogated as well as a general increase in histone acetylation.[54] A human trial using phenylbuturate in ALS patients showed some increase in histone acetylation, but the study did not report whether ALS symptoms improved with treatment.[10]

- Valproic scid

- Valproic acid in mice studies restored histone acetylation levels, increased levels of pro-survival factors, and mice showed improved motor performance.[56] However, while the drug delayed the onset of ALS, it did not increase lifespan or prevent denervation.[57] Human trials of valproic acid in ALS patients did not improve survival or slow progression.[11]

- Trichostatin A

- Trichostatin A trials in mouse ALS models restored histone acetylation in spinal neurons, decreased axon demyelination, and increased survival of mice.[12]

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)

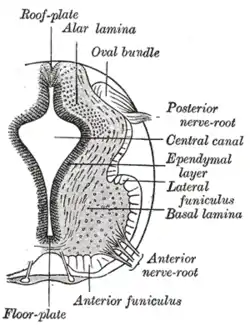

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive motor neuron disease caused by mutations in the SMN1 gene.[58] Symptoms vary greatly with each subset of SMA and the stage of the disease. General symptoms include overall muscle weakness and poor muscle tone including extremities and respiratory muscles leading to difficulty walking, breathing, and feeding. Depending on the type of SMA, the disease can present itself from infancy through adulthood. As SMN protein generally promotes the survival of motor neurons, mutations in SMN1 results in slow degeneration motor neurons leading to progressive system-wide muscle wasting. Specifically, over time, decreased levels of SMN protein results in gradual death of the alpha motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and brain. Muscles depend on connections to motor neurons and the central nervous system to stimulate muscle maintenance and therefore degeneration of motor neurons and subsequent denervation of muscles lead to loss of muscle control and muscle atrophy. The muscles of the lower extremities are often affected first followed by upper extremities and sometimes the muscles of respiration and mastication. In general, proximal muscle is always affected more than distal muscle.

Genetic cause

Spinal muscular atrophy is linked to genetic mutations in the SMN1 (Survival of Motor Neuron 1) gene. The SMN protein is widely expressed in neurons and serves many functions within neurons including spliceosome construction, mRNA axon transport, neurite outgrowth during development, and neuromuscular junction formation. The causal function loss in SMA is currently unknown.

SMN1 is located in a telomeric region of human chromosome 5 and also contains SMN2 in a centromeric region. SMN1 and SMN2 are nearly identical except for a single nucleotide change in SMN2 resulting in an alternative splicing site where intron 6 meets exon 8. This single base pair change leads to only 10-20% of SMN2 transcripts resulting in fully functional SMN protein and 80-90% of transcripts leading to a truncated protein that is rapidly degraded. Most SMA patients have 2 or more copies of the SMN2 gene with more copies resulting in a decrease in disease severity.[59] Most SMA patients have either point mutations or a deletion in exon 7 often leading to a protein product similar to the truncated and degraded version of the SMN2 protein. In SMA patients this small amount of functional SMN2 protein product allows for some neurons to survive.

Epigenetic treatment through SMN2 gene activation

Although SMA is not caused by an epigenetic mechanism, therapeutic drugs that target epigenetic marks may provide SMA patients with some relief, halting or even reversing the progression of the disease. As SMA patients with higher copy numbers of the SMN2 gene have less severe symptoms, researchers predicted that epigenetic drugs that increased SMN2 mRNA expression would increase the amount of functional SMN protein in neurons leading to a reduction in SMA symptoms. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors are the main compounds that have been tested to increase SMN2 mRNA expression. Inhibiting HDACs would allow for hyperacetylation of the SMN2 gene loci theoretically resulting in an increase in SMN2 expression.[40] Many of these HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) are first tested in mouse models of SMA created through a variety of mutations in the mouse SMN1 gene. If the mice show improvement and the drug does not cause very many side effects or toxicity, the drug may be used in human clinical trials. Human trials with all of the below HDAC inhibitors are extremely variable and often impacted by the patient's exact SMA subtype.

- Quisinostat (JNJ-26481585)

- Quisinostat is effective at low doses resulting in some improved neuromuscular function in mouse model of SMA, but survival was not increased.[60] No human trials have been conducted.

- Sodium butyrate

- Sodium butyrate was the first HDAC inhibitor tested in SMA mouse models. It prolonged SMA mouse life span by 35% and showed increased levels of SMN protein in spinal cord tissue.[27][28] However, sodium butyrate has not been used in human trials to date.

- Sodium phenylbutyrate

- Sodium phenylbutyrate increases SMN2 full length mRNA transcripts in cell culture but drug application must be repeated in order to maintain results.[27] Human trials show mixed results with one study showing increased SMA transcript levels in blood and improved motor function,[29] but a larger trial showing no effects on disease progression or motor function.[28]

- Valproic acid

- Valproic acid added to cells from SMA patients increased SMN2 mRNA and protein levels and that the drug directly activates SMN2 promoter.[30][31] In a SMA mouse model, valproic acid was added to the drinking water and restored motor neuron density and increased motor neuron number over a period of 8 months.[32] Human trials are extremely variable showing increased SMN2 levels and increased muscle strength in some trials and absolutely no effects in other trials.[34][33][35][36]

- M344

- M344 is a benzamide that shows promising results in fibroblast cell culture and increases level of splicing factors known to modulate SMN2 transcripts, but the drug was determined toxic and research has not progressed to in vivo testing.[26]

- Trichostatin A

- Trichostatin A treatment shows promising results in mice. In one study, Trichostatin A combined with extra nourishment in early onset mouse SMA models resulted in improved motor function and survival and delays progressive denervation of muscles.[37] A second study in a SMA mouse model showed increased SMN2 transcripts with daily injections.[38] No human trials have been conducted.

- Vorinostat (SAHA)

- Vorinostat is a second generation inhibitor that is fairly non-toxic and found to be effective in cell culture at low concentrations[39] and increases histone acetylation at the SMN2 promoter.[40] In a SMA mouse model, SAHA treatment resulted in weight gain, increased SMN2 transcripts levels in muscles and spinal cord, and motor neuron loss and denervation were halted.[41] No human trials have been conducted.

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease affecting synapses at the neuromuscular junction, whereby antibodies produced primarily in the thymus gland by B-cells associate with postsynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR), along with other NMJ post-synaptic receptors (MuSK-R and low-density lipoprotein receptor). These antibodies include acetylcholine receptor antibodies, MuSK antibodies, and low-density lipoprotein receptor related protein 4 antibodies (LRP4-Ab).[61] Antibody binding to their respective receptors causes the destruction of those receptors, leading to a reduction in the number of postsynaptic acetylcholinergic receptors and a reduction in overall acetylcholine transport. Disease symptoms include muscular weakness that fatigues due to overuse, but improves with rest. Hallmark symptoms due to muscular weakness include ptosis, double vision, dysphagia, as well as aberrant speech.[62]

Myasthenia gravis is a relatively rare disease, occurring in about 3-30 individuals per 100,000, but has been rising over the past couple decades. There exists two variations of myasthenia gravis with respect to age and gender demographics: early-onset myasthenia gravis, which has a higher incidence among females, and late-onset myasthenia gravis, which has a higher incidence among males.[62]

Epigenetic Factors

There has been extensive research on the genetic basis of myasthenia gravis, however evidence does not suggest that it is an inherited disease.[63] There has also been extensive research on the epigenetic contribution to myasthenia gravis.[64] DNA methylation and noncoding RNA, such as miRNA (micro RNA) and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), are epigenetic factors that play a significant role in increasing the likelihood of acquiring myasthenia gravis. In addition, the thymus is a key organ in the immune response that is often negatively affected by abnormal miRNA expression and DNA methylation.

miRNA

Micro RNA (miRNA) are single-stranded non-coding RNAs that bind their target mRNAs. From there, they can regulate gene expression by inhibiting translation or degrading the mRNA strand, oftentimes in B-cells and T-cells of the immunological process. With respect to myasthenia gravis, abnormal miRNA function is associated with immunoregulatory pathogenesis, and each miRNA has its own unique downstream effects.

The thymus is an important endocrine organ implicated in myasthenia gravis. In normal, healthy development, the thymus shrinks in size over time. In those with thymus-associated myasthenia gravis there are correlations with thymomas in late-onset myasthenia gravis as well as thymic hyperplasia with germinal centers in early-onset myasthenia gravis, and each of these conditions can be attributed partly to irregular miRNA function.[65] In late-onset myasthenia gravis subjects, it was shown that miRNA-12a-5p expression was increased in thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis. MiRNA-12a-5p inhibits expression of the gene FoxP3, a gene known to be associated with normal thymus development and whose alteration is attributed to thymomas.[66] Additionally, an association between thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis and decreased miR-376a/miR-376c expression was found. Autoimmune regulation is known to be downregulated in thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis, and in thymus cells with downregulated autoimmune regulation there was simultaneous downregulation in miR-376a, miR-376c, and miRNA-12a-5p expression.[66] In early-onset myasthenia gravis patients, 61 miRNA's were found to be either significantly downregulated or upregulated. The most downregulated miRNA was found to be miR-7-5p, whose target gene is CCL21. CCL21 is known to aberrantly recruit B-cells in the thymus of early-onset myasthenia gravis patients, and was found to be highly expressed in early-onset myasthenia gravis patients, potentially explaining the abnormally large amounts of B cells found in thymic hyperplasia.[67]

Aside from miRNA's corresponding to altered thymus function, there are other several key miRNA's that are correlated with myasthenia gravis. MiR-15 cluster (miR-15a, miR-15b, and miR-15c) was shown to be associated with autoimmunity, in that its downregulation increased CXCL10 expression, a target gene involved in T-cell signaling. CXCL10 expression was also shown to be increased in the thymus of myasthenia gravis patients.[68] Additionally, miR-146 was found to be upregulated in myasthenia gravis patients. In these patients with upregulated miR-146, there was a concurrent increase in proteins that correspond to a wide array of immune responses, specifically TLR4, CD40, and CD80.[69]

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is the epigenetic process by which methyl groups are added to either adenine or cytosine bases, which results in the repression of that sequence when cytosine methylation occurs.[70] DNA methylation was found to be a factor in increasing the likelihood of acquiring myasthenia gravis, albeit this topic has not been widely researched. Research in China has identified the gene CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4) as being highly methylated in myasthenia gravis patients compared to control groups throughout the entire span of the disease. The CTLA-4 gene produces an antigen of the same name that is presented on killer T-cells and allows for the suppression of the immune response. Methylation of this gene represses production of the antigen CTLA-4—a pattern seen in a significant majority of myasthenia gravis patients—and can explain the elevated immune response seen in myasthenia gravis.[71] Furthermore, myasthenia gravis patients with thymic abnormalities (approximately 10-20% of all myasthenia gravis patients)[72] had even higher levels of CTLA-4 methylation than other myasthenia gravis patients. It is not extensively researched why certain genes are hypermethylated in these cases, but information on myasthenia gravis largely points to upregulation of the DNA methyltransferase genes DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B in patients with myasthenia gravis.[73]

In addition to CTLA-4 methylation, hypermethylation of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor gene was seen in patients with thymoma-associated late-onset myasthenia gravis.[74] Growth hormone secretagogue receptor hypermethylation is detected in a wide variety of cancers, however only recently has been correlated with the development of thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis. Although it is seen in approximately 1/4 of thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis subjects, it is not a reliable biomarker for the disease, and its relevance to disease progression is not well known.

Long ncRNA

Long ncRNA (lncRNA) are a second type of non-coding RNA that are key post-transcriptional modifiers of protein-coding gene expression. These also play a significant role in myasthenia gravis. Their aberrant regulation can cause differential expression in downstream genes. For instance, the differential expression of lncRNA interferon gamma antisense RNA negatively regulates the expression of HLA-DRB and HLA-DOB,[74] two genes implicated in the body's autoimmune response by differentiating endogenous and foreign proteins.[75] As seen in myasthenia gravis patients with downregulated lethal (let)-7 lncRNA, it was also found that the level of let-7 lncRNA was negatively correlated with levels of interleukin (IL)-10, a gene responsible for inhibiting cytokine secretion/activation, antigen presentation, and macrophage activity,[76] but also for exhibiting anti-tumor effects.[77] Therefore, the negative correlation between let-7 lncRNA and IL-10 levels and its specific effects on myasthenia gravis development are ambiguous.

In addition to aberrant regulation of downstream target genes, lncRNA also affect expression by acting as competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA). The competing endogenous RNA theory states that transcripts sharing common miRNA binding sites can compete to bind these identical miRNAs, and in this way lncRNAs can bind miRNAs, regulating their downstream binding activity and affecting their function. In the case of myasthenia gravis, the lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene (SNHG) 16 regulates the expression of IL-10 by adsorbing let-7c-5p, a miRNA that commonly associates with IL-10, as a competing endogenous RNA.

Epigenetic Treatments

Diagnosis of myasthenia gravis, individual prognosis, and the level of treatment needed can be determined by detecting the amounts of circulating miRNA.

Immunosuppressants represent a large category in clinical studies for myasthenia gravis treatment, as they reduce the hyperactive immunological response in T-cells presenting acetylcholine receptor-binding antigens.[65] By overexpressing miR-146, studies show that patients with early-onset myasthenia gravis can have antigen-specific suppressive effects. This has implications in reducing the immune response of myasthenia gravis patients and improving prognosis. Likewise, miR-155 is proven to be correlated with myasthenia gravis-associated thymic inflammation and immune response. Research is being conducted whereas repression of miR-155 could reduce these aberrant effects.[65] Lastly, the miRNA's miR-150-5p and miR-21-5p are consistently shown to be elevated in myasthenia gravis patients with acetylcholinergic receptor antibodies (in contrast to the MuSK-binding variant of myasthenia gravis), therefore these two miRNA's are reliable biomarkers in detecting this variant of myasthenia gravis.[78]

Neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system

Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia among the elderly. The disease is characterized behaviorally by chronic and progressive decline in cognitive function, beginning with short-term memory loss, and neurologically by buildup of misfolded tau protein and associated neurofibrillary tangles, and by amyloid-beta senile plaques amyloid-beta senile plaques. Several genetic factors have been identified as contributing to AD, including mutations to the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilins 1 and 2 genes, and familial inheritance of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4. In addition to these common factors, there are a number of other genes that have shown altered expression in Alzheimer's disease, some of which are associated with epigenetic factors.

Epigenetic factors

- ncRNA

- ncRNA that is encoded antisense from an intron within the beta-amyloid cleaving enzyme gene, BACE1, is involved in AD.[5] This ncRNA, BACE1-AS (for antisense), which overlaps exon 6 of BACE1, is involved in increasing the stability of the BACE1 mRNA transcript. As that gene's name suggests, BACE1 is an enzymatic protein that cleaves the Amyloid Precursor Protein into the insoluble amyloid beta form, which then aggregates into senile plaques. With increased stability of BACE1 mRNA resulting from BACE1-AS, more BACE1 mRNA is available for translation into BACE1 protein.

- miRNA

- factors have not consistently been shown to play a role in progression of AD. miRNAs are involved in post-transcriptional gene silencing via inhibiting translation or involvement in RNAi pathways. Some studies have shown upregulation of miRNA-146a, which differentially regulates neuroimmune-related Interleukin-1R associated kinases IRAK1 and IRAK2 expression, in human AD brain, while other studies have shown upregulation or downregulation of miRNA-9 in brain.[79]

- DNA methylation

- In Alzheimer's disease cases, global DNA hypomethylation and gene-specific hypermethylation has been observed, though findings have varied between studies, especially in studies of human brains. Hypothetically, global hypomethylation should be associated with global increases in transcription, since CpG islands are most prevalent in gene promoters; gene-specific hypermethylation, however, would indicate that these hypermethylated genes are repressed by the methylation marks. Generally, repressive hypermethylation of genes related to learning and memory has been observed in conjunction with derepressive hypomethylation of neuroinflammatory genes and genes related to pathological expression of Alzheimer's disease. Reduced methylation has been found in the long-term memory-associated temporal neocortex neurons in monozygotic twins with Alzheimer's disease compared to the healthy twin.[80] Global hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides has also been observed in hippocampus[81] and in entorhinal cortex layer II[82] of human AD patients, both of which are susceptible to AD pathology. These results, found by probing with immunoassays, have been challenged by studies that interrogate DNA sequence by bisulfite sequencing, a CpG transformation technique which is sensitive to CpG methylation status, in which global hypomethylation has been observed.[83][84]

- COX-2

- At the individual gene level, hypomethylation and thus derepression of COX-2 occurs, inhibition of which reduces inflammation and pain, and hypermethylation of BDNF, a neurotrophic factor important for long-term memory.[84] Expression of CREB, an activity-dependent transcription factor involved in regulating BDNF among many other genes, has also been shown to be hypermethylated, and thus repressed, in AD brains, further reducing BDNF transcription.[84] Furthermore, synaptophysin (SYP), the major synaptic vesicle protein-encoding gene, has been shown to be hypermethylated and thus repressed, and transcription factor NF-κB, which is involved in immune signaling, has been shown to be hypomethylated and thus derepressed.[84] Taken together, these results have elucidated a role for dysregulation of genes involved in learning and memory and synaptic transmission, as well as with immune response.

- Hypomethylation

- has been observed in promoters of presenilin 1,[85] GSK3beta, which phosphorylates tau protein,[86] and BACE1,[87] an enzyme that cleaves APP into the amyloid-beta form, which in turn aggregates into insoluble senile plaques. Repressive hypermethylation caused by amyloid-beta has been observed at the promoter of NEP, the gene for neprilysin, which is the major amyloid-beta clearing enzyme in the brain.[88] This repression of NEP could result in a feed-forward buildup of senile plaques; combined with the observed increase in AD brains of BACE1-AS and corresponding increases in BACE1 protein and amyloid beta,[5] multiple levels of epigenetic regulation may be involved in controlling amyloid-beta formation, clearance or aggregation, and senile plaque deposition. There may be some effect of age in levels of DNA methylation at specific gene promoters, as one study found greater levels of methylation at APP promoters in AD patients up to 70 years old, but lower levels of methylation in patients greater than 70 years old.[89] Studies on differential DNA methylation in human AD brains remain largely inconclusive possibly owing to the high degree of variability between individuals and to the numerous combinations of factors that may lead to AD.

- Histone marks

- Acetylation of lysine residues on histone tails is typically associated with transcriptional activation, whereas deacetylation is associated with transcriptional repression. There are few studies investigating specific histone marks in AD. These studies have elucidated a decrease in acetylation of lysines 18 and 23 on N-terminal tails of histone 3 (H3K18 and H3K23, respectively)[90] and increases in HDAC2 in AD brains[91] - both marks related to transcriptional repression. Age-related cognitive decline has been associated with deregulation of H4K12 acetylation, a cognitive effect that was restored in mice by induction of this mark.[92]

Treatments

Treatment for prevention or management of Alzheimer's disease has proven troublesome since the disease is chronic and progressive, and many epigenetic drugs act globally and not in a gene-specific manner. As with other potential treatments to prevent or ameliorate symptoms of AD, these therapies do not work to cure, but only ameliorate symptoms of the disease temporarily, underscoring the chronic, progressive nature of AD, and the variability of methylation in AD brains.

- Folate and other B vitamins

- B vitamins are involved in the metabolic pathway that leads to SAM production. SAM is the donor of the methyl group utilized by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) to methylate CpGs. Using animal models, Fuso et al. have demonstrated restoration of methylation at previously hypomethylated promoters of presenilin 1, BACE1 and APP[93] - a hypothetically stable epigenetic modification that should repress those genes and slow the progression of AD. Dietary SAM supplementation has also been shown to reduce oxidative stress and delay buildup of neurological hallmarks of AD such as amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau protein in transgenic AD mice.

- AZA

- Khan and colleagues have demonstrated a potential role for neuroglobinin attenuating amyloid-related neurotoxicity.[94] 5-aza-2' deoxycitidine (AZA, or decitabine), a DNMT inhibitor, has shown some evidence for regulating neuroglobin expression, though this finding has not been tested in AD models.[95]

- Histone-directed treatments

- Though studies of histone marks in AD brains are few in number, several studies have looked at the effects of HDACis in treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Class I and II HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A, vorinostat, and sodium butyrate, and Class III HDACis, such as nicotinamide, have been effective at treating symptoms in animal models of AD. While promising as a therapeutic in animal models, studies on the long-term efficacy of HDACis and human trials have yet to be conducted.

- Sodium butyrate

- Sodium butyrate is a class I and II HDACi and has been shown to recover learning and memory after 4 weeks,[13] decrease phosphorylated tau protein, and restore dendritic spine density in the hippocampus of AD transgenic mice.[14] Histone acetylation resulting from diffuse sodium butyrate application is especially prevalent in the hippocampus, and genes involved in learning and memory showed increased acetylation in AD mice treated with this drug.[15]

- Trichostatin A

- Trichostatin A is also a class I and II HDACi that rescues fear learning in a fear conditioning paradigm in transgenic AD mice to wild type levels via acetylation on histone 4 lysine tails.[17]

- Vorinostat

- Vorinostat is a class I and II HDACi that has been shown to be especially effective at inhibiting HDAC2 and restoring memory functions in non-AD models of learning deficits.[96] One study showed vorinostat is effective at reversing contextual memory deficits in transgenic AD mice.[16]

Huntington's (HD)

Huntington's disease (HD) is an inherited disorder that causes progressive degeneration of neurons within the cerebral cortex and striatum of the brain[97] resulting in loss of motor functions (involuntary muscle contractions), decline in cognitive ability (eventually resulting in dementia), and changes in behavior.[6]

Genetics and underlying causes

Huntington's is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation expanding the number of glutamine codon repeats (CAG) within the Huntingtin gene (Htt).[97] The Htt gene encodes for the huntingtin protein which plays a role in normal development but its exact function remains unknown.[98] The length of this CAG repeat correlates with the age-of-onset of the disease. The average person without Huntington's has less than 36 CAG repeats present within the Htt gene. When this repeat length exceeds 36, the onset of neuronal degradation and the physical symptoms of Huntington's can range from as early as 5 years of age (CAG repeat > 70) to as late as 80 years of age (CAG repeat < 39).[99]

This CAG expansion results in mRNA downregulation of specific genes, decreased histone acetylation, and increased histone methylation.[100][101] The exact mechanism of how this repeat causes gene dysregulation is unknown, but epigenome modification may play a role. For early-onset Huntington's (ages 5–15), both transgenic mice and mouse striatal cell lines show brain specific histone H3 hypoacetylation and decreased histone association at specific downregulated genes within the striatum (namely Bdnf, Cnr1, Drd2 - dopamine 2 receptor, and Penk1 - preproenkephalin).[102] For both late- and early-onset Huntington's, the H3 and H4 core histones associated with these downregulated genes in Htt mutants have hypoacetylation (decreased acetylation) compared to wild-type Htt.[101][102] This hypoacetylation is sufficient to cause tighter chromatin packing and mRNA downregulation.[101]

Along with H3 hypoacetylation, both human patients and mice with the mutant Htt have increased levels of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation.[100] This increase in H3-K9 trimethylation is linked to an increased expression of the methyltransferase ESET/SETDB1 (ERG-associated protein with SET domain (ESET)), which targets and trimethylates H3-K9 residues.[100] It is proposed that this hypermethylation may account for the onset of specific gene repression in Htt mutants.[100]

HDAC inhibitors

Huntington patients and both mouse and Drosophila models show histone H3 and H4 hypoacetylation. There are currently no treatments for the disease but numerous HDAC inhibitors have been tested and shown to reverse the certain symptoms caused by the Htt mutation.

- Sodium Butyrate

- Sodium butyrate treatment slowed neuronal degeneration in Drosophila models.[18] Sodium butyrate treatment also increased histone H3 acetylation and normalized mRNA levels for mutant Htt downregulated genes.[102]

- Valproic acid

- Valproic acid treatment increased mutant Htt H3 and H4 acetylation levels comparable to wild-type Htt in Drosophila models.[18]

- Sodium Phenylbutyrate

- Sodium phenylbutyrate phase II human triasl with 12 to 15 g/day showed restored mRNA levels of Htt mutant repressed genes but also had adverse side effects such as nausea, headaches, and gain instability.[103] Phenylbutyrate has also been shown to increase histone acetylation, decrease histone methylation, increase survival rate, and decrease the rate of neuronal degradation in Htt mutant mouse models.[19]

- Trichostatin A

- Trichostatin A (TSA) treatment increased mutant Htt H3 and H4 acetylation levels comparable to wild-type Htt in Drosophila models.[18] TSA treatment has also been shown to increase alpha-tubulin lysine 40 acetylation in mouse striatal cells and increase intracellular transport of BDNF, a brain-derived neurotrophic factor that function in nerve growth and maintenance within the brain.[104][20]

- Vorinostat (SAHA)

- Vorinostat treatment slowed photoreceptor degeneration and improved longevity of adult Htt mutant Drosophila.[18] Like TSA, SAHA treatment increased alpha-tubulin lysine 40 acetylation in mouse striatal cells and also increased intracellular transport of BDNF.

Parkinson's Disease (PD)

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra by causes unknown. Several genes and environmental factors (e.g. pesticide exposure) may play a role in onset of PD. Hallmarks include mutations to the alpha-synuclein gene, SNCA, as well as PARK2, PINK1, UCHL1, DJ1, and LRRK2 genes, and fibrillar accumulation of Lewy bodies from misfolded alpha-synuclein. Symptoms are most noticeably manifested in disorders of movement, including shaking, rigidity, deficits in making controlled movements, and slow and difficult walking. The late stages of the disease result in dementia and depression. Levodopa and dopaminergic therapy may ameliorate symptoms, though there is no treatment to halt progression of the disease.

Epigenetic factors

- ncRNA

- Reductions of miR-133b correlated to decreased numbers of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain of PD patients.[105] miR-132, meanwhile, is negatively correlated with dopaminergic neuron differentiation in the midbrain.[106] miR-7 and miR-153 act to reduce alpha-synuclein levels (a hallmark of PD) but are reduced in PD brain.[107]

- DNA methylation

- Neurons of PD patients show hypomethylation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha encoding sequence, overexpression of which leads to apoptosis of neurons.[108] Cerebrospinal fluid of PD patients also shows elevated TNF alpha.[109] Research indicates there may be a link between DNA methylation and SNCA expression.[110][111] Furthermore, human and mouse models have shown reduction of nuclear DNMT1 levels in PD subjects, resulting in hypomethylated states associated with transcriptional repression.[112]

- Histone marks

- alpha-synuclein, the protein encoded by SNCA, can associate with histones and prevent their acetylation in concert with the HDACs HDAC1 and Sirt2.[25][113] Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that alpha-synuclein binds histone 3 and inhibits its acetylation in Drosophila.[25] Dopamine depletion in Parkinson's disease is associated with repressive histone modifications, including reduced H3K4me3, and lower levels of H3 and H4 lysine acetylation after levodopa therapy (a common treatment of PD).

Treatments

Epigenetic treatments tested in models of PD are few, though some promising research has been conducted. Most treatments investigated thus far are directed at histone modifications and analysis of their roles in mediating alpha-synuclein expression and activity. Pesticides and paraquat increase histone acetylation, producing neurotoxic effects similar to those seen in PD, such as apoptosis of dopaminergic cells.[114] Despite this, treatment with HDACis[115] seems to have a neuroprotective effect.

- Sodium butyrate

- Several studies using different animal models have demonstrated that sodium butyrate may be effective in reducing alpha-synuclein-related neurotoxicity.[21][22] In Drosophila, sodium butyrate improved locomotor impairment and reduced early mortality rates.[23]

- Valproic acid

- In an inducible rat model of PD, valproic acid had a neuroprotective effect by preventing translocation of alpha-synuclein into cell nuclei.[24]

- Vorinostat

- In an alpha-synuclein overexpressing Drosophila model of PD, vorinostat (as well as sodium butyrate) reduced alpha-synuclein-mediated neurotoxicity.[25]

- siRNA inhibition of SIRT2

- Treatment with SIRT2 inhibiting siRNA leads to reduced alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity AK-1 or AGK-2.[113]

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating neurodegenerative disease that does not have a confirmed cause, but is widely considered to be an autoimmune disease in nature.[116] It is indicated by demyelination of the nerves of the brain and spinal cord. Its symptoms are unique in nature and vary, but include those that have degenerative effects in the eyes and limbs. These can present themselves as numbness or atrophy, shock like sensations, paralysis, as well as lack of coordination or tremors, within the extremities. Within the eye, multiple sclerosis can cause blurriness, double vision, pain, or vision loss. Multiple sclerosis effects can be presented throughout other realms of the body, but is largely characterized by these main symptoms. Some of these can include loss of sexual or excretory function and epilepsy. While there are a few subcategories of multiple sclerosis, in most instances, the disease afflicts in a relapsing nature, where relapses of symptoms might not occur for extended periods of time, yielding more to the uncertainty of the disease. There is no known cure for MS, but measures can be taken post relapse to regain loss of function and the symptoms can be mitigated via therapeutic or medicinal means.[117]

Epigenetic Factors

Because of the outside factors that precede multiple sclerosis and the heritability typically occurring within the mother, it is thought to have an epigenetic cause. Some factors that may increase the incidence of MS are smoking, vitamin deficiency, and a history of some viral infections—which are factors that can induce epigenetic change.[118]

Human Leukocyte Antigen-DRB1*15 Allele

Human leukocyte antigen-DRB1*15 haplotype is a potential risk factor of MS. Because of the increased likelihood of the mother's human leukocyte antigen-DRB1*15 allele being passed onto their children, this contributes to the instances of MS being more prevalent from the mother. HLA-DRB1 is thought to be regulated via epigenetic means. The correlation of MS and this allele is speculated to be due to the presence of hypomethylation in the CpG island of HLA-DRB1, and those that carry the allele tend to exhibit this hypomethylation. HLA-DRB1 exon 2 is a particular region where evidence has shown that methylation is shown to be important in regulation. Research has furthered the evidence that variation in HLA-DRB1 DMR, which is a mechanism that is methylation regulated, that in turn regulates increased HLA-DRB1 expression, displays an increased risk for MS, and the exhibition of the disease.[118][119]

miRNA

Higher levels of expression of specific types of miRNA are often seen in the brain of those afflicted, showing an association of these types of miRNA and MS. Higher expression of miR-155 and miR-326 is often associated with CD4+T cell differentiation, and with this differentiation, instances of autoimmune encephalitis occur, which is the link with which it is thought that smoking can induce epigenetic changes that increase susceptibility to MS. Higher expression levels of miR-18b, miR-493, miR-599, and miR-96 are often seen in patients diagnosed with MS. miR-145 detection appears to be a promising future diagnostic tool due to its high specificity of 90% and sensitivity of 89.5% in whole blood testing due to its capability of distinguishing healthy patients versus those with MS. A symptom associated with MS patients is white matter lesions in the brain, and these lesions when biopsied showed higher expression of miR-155, miR-326 and miR-34a. These are especially notable due to the fact that overexpression of these miRNA's cause downregulation of CD47, leading to myelin phagocytosis, because of CD47's role of inhibiting macrophage activity.[120]

DNA Methylation

MS patients can be identified through observation of abnormal DNA methylation patterns in genes responsible for inflammation and myelination factor expression. Methylation occurs in the genomic region, CpG island, and is imperative in regulation of transcription. A methylated CpG region typically is the mechanism that will silence a gene, whereas a hypomethylated region is able to induce transcription. Using methylation inhibitors it has been shown that allowing higher proliferation of T cells can be achieved by preventing silencing. Abnormalities in methylation patterns increase the generation of CD4+T auto reactive. Hypomethylation of CpG regions of the PAD2 gene, a regulator of MBP which in turn regulates myelin, is also associated with higher instances of MS. This hypomethylation leads to overexpression of the PAD2 gene. These patterns have been observed in the white matter of patients with MS. While methylation is an indicator of MS, its effects are more specialized to location in MS, for example, where these patterns are observed in white matter.[120]

Histone Modifications

Association of abnormal histone modification in MS patients can be found in lesions located in the brain, with most instances of this being observed in patients over time and in lesions located in the frontal lobe. Higher instance of histone acetylation can be seen in patients afflicted over time, but this is counteracted by lower instances of histone acetylation in lesions found on the brain early in the course of the disease. The mechanisms by which histone modifications work in the progression of MS are unconfirmed, but changes in acetylation are often associated with the disease.

HDAC Inhibitors

Trichostatin

Positive responses were observed in animal trials utilizing this HDAC inhibitor, associated with mediation of inflammatory pathways and thus resulting in lower instances of inflammatory responses in the brain. It was also shown to be effective in decreasing levels of disability when the mice were in a relapsing stage of MS. Trichostatin's mediation of symptoms is not well known but is thought to work in increasing acetylation at the H3 and H4 histones in CD4+T cells where MS patients often display differences in acetylation levels at these histones that control patients do not.

Vorinostat

Animal trials were utilized along with the testing of human myeloid dendritic cells. Not much is known about the mechanisms of Vorinostat, however regulation of Th1/Th17 cytokine expression, which are responsible for inducing inflammation, were observed, thereby decreasing instances of inflammation and demyelination. Decreased patterns of T cell proliferation were also observed, similar to how Trichostatin mediates disease symptoms.[121]

Valpropic Acid

Valpropic acid has been shown to have positive results in animal trials, in the mitigation of the disease by regulating the severity and duration of MS. Its mechanism is decreasing the presentation of miRNA. Its mechanism for such has been observed in rats by shifting Th1 and Th17 to Th2 (responsible for inducing inflammation), thereby downregulating miRNA expression in inflammatory cytokines, tumor mediating mechanisms, and the spine. This is another instance in which T cell expression regulation is present, by preventing proliferation through interference of its pathway, similar to Trichostatin and Vorinostat. Another effect of VPA is its prevention of macrophage and lymphocyte proliferation in the spinal cords of MS rats. Currently, no HDAC inhibitors are in use for the mitigation of symptoms in MS patients however, some are in pre-clinical trials at this time. [120]

See also

References

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 600882 Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease, Axonal, Type 2B; CMT2B - 600882

- Sghirlanzoni A, Pareyson D, Lauria G (June 2005). "Sensory neuron diseases". review. The Lancet. Neurology. 4 (6): 349–61. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70096-X. PMID 15907739. S2CID 35053543.

- Goll MG, Bestor TH (2005). "Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74: 481–514. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. PMID 15952895.

- Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES (February 2007). "The mammalian epigenome". review. Cell. 128 (4): 669–81. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. PMID 17320505. S2CID 2722988.

- Faghihi MA, Modarresi F, Khalil AM, Wood DE, Sahagan BG, Morgan TE, Finch CE, St Laurent G, Kenny PJ, Wahlestedt C (July 2008). "Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase". primary. Nature Medicine. 14 (7): 723–30. doi:10.1038/nm1784. PMC 2826895. PMID 18587408.

- Urdinguio RG, Sanchez-Mut JV, Esteller M (November 2009). "Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological diseases: genes, syndromes, and therapies". The Lancet. Neurology. 8 (11): 1056–72. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70262-5. PMID 19833297. S2CID 25946604.

- Peedicayil J (April 2013). "Epigenetic drugs for Alzheimer's disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 75 (4): 1152–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04444.x. PMC 3612735. PMID 22905989.

- Del Signore SJ, Amante DJ, Kim J, Stack EC, Goodrich S, Cormier K, Smith K, Cudkowicz ME, Ferrante RJ (April 2009). "Combined riluzole and sodium phenylbutyrate therapy in transgenic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice". primary. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 10 (2): 85–94. doi:10.1080/17482960802226148. PMID 18618304. S2CID 24124109.

- Petri S, Kiaei M, Kipiani K, Chen J, Calingasan NY, Crow JP, Beal MF (April 2006). "Additive neuroprotective effects of a histone deacetylase inhibitor and a catalytic antioxidant in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Neurobiology of Disease. 22 (1): 40–9. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2005.09.013. PMID 16289867. S2CID 22794616.

- Cudkowicz ME, Andres PL, Macdonald SA, Bedlack RS, Choudry R, Brown RH, Zhang H, Schoenfeld DA, Shefner J, Matson S, Matson WR, Ferrante RJ (April 2009). "Phase 2 study of sodium phenylbutyrate in ALS". primary. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. 10 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1080/17482960802320487. PMID 18688762. S2CID 12390136.

- Piepers S, Veldink JH, de Jong SW, van der Tweel I, van der Pol WL, Uijtendaal EV, Schelhaas HJ, Scheffer H, de Visser M, de Jong JM, Wokke JH, Groeneveld GJ, van den Berg LH (August 2009). "Randomized sequential trial of valproic acid in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". primary. Annals of Neurology. 66 (2): 227–34. doi:10.1002/ana.21620. PMID 19743466. S2CID 44949619.

- Yoo YE, Ko CP (September 2011). "Treatment with trichostatin A initiated after disease onset delays disease progression and increases survival in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". primary. Experimental Neurology. 231 (1): 147–59. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.003. PMID 21712032. S2CID 42608157.

- Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Wang X, Dobbin M, Tsai LH (May 2007). "Recovery of learning and memory is associated with chromatin remodelling". primary. Nature. 447 (7141): 178–82. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..178F. doi:10.1038/nature05772. PMID 17468743. S2CID 36395789.

- Ricobaraza A, Cuadrado-Tejedor M, Marco S, Pérez-Otaño I, García-Osta A (May 2012). "Phenylbutyrate rescues dendritic spine loss associated with memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease". primary. Hippocampus. 22 (5): 1040–50. doi:10.1002/hipo.20883. PMID 21069780. S2CID 20052391.

- Govindarajan N, Agis-Balboa RC, Walter J, Sananbenesi F, Fischer A (2011). "Sodium butyrate improves memory function in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model when administered at an advanced stage of disease progression". primary. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 26 (1): 187–97. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110080. PMID 21593570.

- Kilgore M, Miller CA, Fass DM, Hennig KM, Haggarty SJ, Sweatt JD, Rumbaugh G (March 2010). "Inhibitors of class 1 histone deacetylases reverse contextual memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease". primary. Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (4): 870–80. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.197. PMC 3055373. PMID 20010553.

- Francis YI, Fà M, Ashraf H, Zhang H, Staniszewski A, Latchman DS, Arancio O (2009). "Dysregulation of histone acetylation in the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 18 (1): 131–9. doi:10.3233/JAD-2009-1134. PMC 8962655. PMID 19625751.

- Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, Poelman M, McCampbell A, Apostol BL, Kazantsev A, Schmidt E, Zhu YZ, Greenwald M, Kurokawa R, Housman DE, Jackson GR, Marsh JL, Thompson LM (October 2001). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila". primary. Nature. 413 (6857): 739–43. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..739S. doi:10.1038/35099568. PMID 11607033. S2CID 4419980.

- Gardian G, Browne SE, Choi DK, Klivenyi P, Gregorio J, Kubilus JK, Ryu H, Langley B, Ratan RR, Ferrante RJ, Beal MF (January 2005). "Neuroprotective effects of phenylbutyrate in the N171-82Q transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease". primary. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (1): 556–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.M410210200. PMID 15494404.

- Dompierre JP, Godin JD, Charrin BC, Cordelières FP, King SJ, Humbert S, Saudou F (March 2007). "Histone deacetylase 6 inhibition compensates for the transport deficit in Huntington's disease by increasing tubulin acetylation". primary. The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (13): 3571–83. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0037-07.2007. PMC 6672116. PMID 17392473.

- Zhou W, Bercury K, Cummiskey J, Luong N, Lebin J, Freed CR (April 2011). "Phenylbutyrate up-regulates the DJ-1 protein and protects neurons in cell culture and in animal models of Parkinson disease". primary. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (17): 14941–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.211029. PMC 3083206. PMID 21372141.

- Rane P, Shields J, Heffernan M, Guo Y, Akbarian S, King JA (June 2012). "The histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, alleviates cognitive deficits in pre-motor stage PD". primary. Neuropharmacology. 62 (7): 2409–12. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.01.026. PMID 22353286. S2CID 23078279.

- St Laurent R, O'Brien LM, Ahmad ST (August 2013). "Sodium butyrate improves locomotor impairment and early mortality in a rotenone-induced Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease". primary. Neuroscience. 246: 382–90. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.037. PMC 3721507. PMID 23623990.

- Monti B, Gatta V, Piretti F, Raffaelli SS, Virgili M, Contestabile A (February 2010). "Valproic acid is neuroprotective in the rotenone rat model of Parkinson's disease: involvement of alpha-synuclein". primary. Neurotoxicity Research. 17 (2): 130–41. doi:10.1007/s12640-009-9090-5. PMID 19626387. S2CID 40159513.

- Kontopoulos E, Parvin JD, Feany MB (October 2006). "Alpha-synuclein acts in the nucleus to inhibit histone acetylation and promote neurotoxicity". primary. Human Molecular Genetics. 15 (20): 3012–23. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl243. PMID 16959795.

- Riessland M, Brichta L, Hahnen E, Wirth B (August 2006). "The benzamide M344, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, significantly increases SMN2 RNA/protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy cells". primary. Human Genetics. 120 (1): 101–10. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0186-1. PMID 16724231. S2CID 24804136.

- Andreassi C, Angelozzi C, Tiziano FD, Vitali T, De Vincenzi E, Boninsegna A, Villanova M, Bertini E, Pini A, Neri G, Brahe C (January 2004). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN expression in vitro: relevance for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy". European Journal of Human Genetics. 12 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201102. PMID 14560316.

- Mercuri E, Bertini E, Messina S, Solari A, D'Amico A, Angelozzi C, Battini R, Berardinelli A, Boffi P, Bruno C, Cini C, Colitto F, Kinali M, Minetti C, Mongini T, Morandi L, Neri G, Orcesi S, Pane M, Pelliccioni M, Pini A, Tiziano FD, Villanova M, Vita G, Brahe C (January 2007). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of phenylbutyrate in spinal muscular atrophy". primary. Neurology. 68 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000249142.82285.d6. PMID 17082463. S2CID 30429093.

- Brahe C, Vitali T, Tiziano FD, Angelozzi C, Pinto AM, Borgo F, Moscato U, Bertini E, Mercuri E, Neri G (February 2005). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN gene expression in spinal muscular atrophy patients". primary. European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (2): 256–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201320. PMID 15523494.

- Sumner CJ, Huynh TN, Markowitz JA, Perhac JS, Hill B, Coovert DD, Schussler K, Chen X, Jarecki J, Burghes AH, Taylor JP, Fischbeck KH (November 2003). "Valproic acid increases SMN levels in spinal muscular atrophy patient cells". primary. Annals of Neurology. 54 (5): 647–54. doi:10.1002/ana.10743. PMID 14595654. S2CID 7983521.

- Brichta L, Hofmann Y, Hahnen E, Siebzehnrubl FA, Raschke H, Blumcke I, Eyupoglu IY, Wirth B (October 2003). "Valproic acid increases the SMN2 protein level: a well-known drug as a potential therapy for spinal muscular atrophy". primary. Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (19): 2481–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg256. PMID 12915451.

- Tsai LK, Tsai MS, Lin TB, Hwu WL, Li H (November 2006). "Establishing a standardized therapeutic testing protocol for spinal muscular atrophy". primary. Neurobiology of Disease. 24 (2): 286–95. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.004. PMID 16952456. S2CID 31974628.

- Weihl CC, Connolly AM, Pestronk A (August 2006). "Valproate may improve strength and function in patients with type III/IV spinal muscle atrophy". primary. Neurology. 67 (3): 500–1. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000231139.26253.d0. PMID 16775228. S2CID 13138072.

- Piepers S, Cobben JM, Sodaar P, Jansen MD, Wadman RI, Meester-Delver A, Poll-The BT, Lemmink HH, Wokke JH, van der Pol WL, van den Berg LH (August 2011). "Quantification of SMN protein in leucocytes from spinal muscular atrophy patients: effects of treatment with valproic acid". primary. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 82 (8): 850–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2009.200253. PMID 20551479. S2CID 27844635.

- Swoboda KJ, Scott CB, Crawford TO, Simard LR, Reyna SP, Krosschell KJ, Acsadi G, Elsheik B, Schroth MK, D'Anjou G, LaSalle B, Prior TW, Sorenson SL, Maczulski JA, Bromberg MB, Chan GM, Kissel JT (August 2010). "SMA CARNI-VAL trial part I: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of L-carnitine and valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy". primary. PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e12140. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512140S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012140. PMC 2924376. PMID 20808854.

- Darbar IA, Plaggert PG, Resende MB, Zanoteli E, Reed UC (March 2011). "Evaluation of muscle strength and motor abilities in children with type II and III spinal muscle atrophy treated with valproic acid". primary. BMC Neurology. 11: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-36. PMC 3078847. PMID 21435220.

- Narver HL, Kong L, Burnett BG, Choe DW, Bosch-Marcé M, Taye AA, Eckhaus MA, Sumner CJ (October 2008). "Sustained improvement of spinal muscular atrophy mice treated with trichostatin A plus nutrition". primary. Annals of Neurology. 64 (4): 465–70. doi:10.1002/ana.21449. PMID 18661558. S2CID 5595968.

- Avila AM, Burnett BG, Taye AA, Gabanella F, Knight MA, Hartenstein P, Cizman Z, Di Prospero NA, Pellizzoni L, Fischbeck KH, Sumner CJ (March 2007). "Trichostatin A increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy". primary. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (3): 659–71. doi:10.1172/JCI29562. PMC 1797603. PMID 17318264.

- Hahnen E, Eyüpoglu IY, Brichta L, Haastert K, Tränkle C, Siebzehnrübl FA, Riessland M, Hölker I, Claus P, Romstöck J, Buslei R, Wirth B, Blümcke I (July 2006). "In vitro and ex vivo evaluation of second-generation histone deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy". primary. Journal of Neurochemistry. 98 (1): 193–202. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03868.x. PMID 16805808.

- Kernochan LE, Russo ML, Woodling NS, Huynh TN, Avila AM, Fischbeck KH, Sumner CJ (May 2005). "The role of histone acetylation in SMN gene expression". primary. Human Molecular Genetics. 14 (9): 1171–82. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi130. PMID 15772088.

- Riessland M, Ackermann B, Förster A, Jakubik M, Hauke J, Garbes L, Fritzsche I, Mende Y, Blumcke I, Hahnen E, Wirth B (April 2010). "SAHA ameliorates the SMA phenotype in two mouse models for spinal muscular atrophy". primary. Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (8): 1492–506. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq023. PMID 20097677.

- Dewey CM, Cenik B, Sephton CF, Johnson BA, Herz J, Yu G (June 2012). "TDP-43 aggregation in neurodegeneration: are stress granules the key?". review. Brain Research. 1462: 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.032. PMC 3372581. PMID 22405725.

- Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, Bennett CF, Cleveland DW, Yeo GW (June 2012). "Misregulated RNA processing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". review. Brain Research. 1462: 3–15. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.059. PMC 3707312. PMID 22444279.

- Rouaux C, Jokic N, Mbebi C, Boutillier S, Loeffler JP, Boutillier AL (December 2003). "Critical loss of CBP/p300 histone acetylase activity by caspase-6 during neurodegeneration". primary. The EMBO Journal. 22 (24): 6537–49. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg615. PMC 291810. PMID 14657026.

- Battistini S, Ricci C, Lotti EM, Benigni M, Gagliardi S, Zucco R, Bondavalli M, Marcello N, Ceroni M, Cereda C (June 2010). "Severe familial ALS with a novel exon 4 mutation (L106F) in the SOD1 gene". primary. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 293 (1–2): 112–5. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2010.03.009. PMID 20385392. S2CID 24895265.

- Bruijn LI, Houseweart MK, Kato S, Anderson KL, Anderson SD, Ohama E, Reaume AG, Scott RW, Cleveland DW (September 1998). "Aggregation and motor neuron toxicity of an ALS-linked SOD1 mutant independent from wild-type SOD1". primary. Science. 281 (5384): 1851–4. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1851B. doi:10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. PMID 9743498.

- Furukawa Y, Fu R, Deng HX, Siddique T, O'Halloran TV (May 2006). "Disulfide cross-linked protein represents a significant fraction of ALS-associated Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase aggregates in spinal cords of model mice". primary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (18): 7148–53. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.7148F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0602048103. PMC 1447524. PMID 16636274.

- Boillée S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW (October 2006). "ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors". review. Neuron. 52 (1): 39–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. PMID 17015226. S2CID 12968143.

- Cudkowicz ME, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PE, Chin W, Geller B, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Hosler BA, Horvitz HR, Brown RH (February 1997). "Epidemiology of mutations in superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". primary. Annals of Neurology. 41 (2): 210–21. doi:10.1002/ana.410410212. PMID 9029070. S2CID 25595595.

- Todd TW, Petrucelli L (August 2016). "Insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) repeat expansions". review. Journal of Neurochemistry. 138 Suppl 1: 145–62. doi:10.1111/jnc.13623. PMID 27016280.

- Yoshimura S, Gerondopoulos A, Linford A, Rigden DJ, Barr FA (October 2010). "Family-wide characterization of the DENN domain Rab GDP-GTP exchange factors". primary. The Journal of Cell Biology. 191 (2): 367–81. doi:10.1083/jcb.201008051. PMC 2958468. PMID 20937701.

- Deng HX, Chen W, Hong ST, Boycott KM, Gorrie GH, Siddique N, et al. (August 2011). "Mutations in UBQLN2 cause dominant X-linked juvenile and adult-onset ALS and ALS/dementia". primary. Nature. 477 (7363): 211–5. Bibcode:2011Natur.477..211D. doi:10.1038/nature10353. PMC 3169705. PMID 21857683.

- Rouaux C, Loeffler JP, Boutillier AL (September 2004). "Targeting CREB-binding protein (CBP) loss of function as a therapeutic strategy in neurological disorders". review. Biochemical Pharmacology. 68 (6): 1157–64. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.035. PMID 15313413.

- Ryu H, Smith K, Camelo SI, Carreras I, Lee J, Iglesias AH, Dangond F, Cormier KA, Cudkowicz ME, Brown RH, Ferrante RJ (June 2005). "Sodium phenylbutyrate prolongs survival and regulates expression of anti-apoptotic genes in transgenic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice". primary. Journal of Neurochemistry. 93 (5): 1087–98. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03077.x. PMID 15934930.

- Corcoran LJ, Mitchison TJ, Liu Q (March 2004). "A novel action of histone deacetylase inhibitors in a protein aggresome disease model". primary. Current Biology. 14 (6): 488–92. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.003. PMID 15043813. S2CID 6465499.

- Crochemore C, Virgili M, Bonamassa B, Canistro D, Pena-Altamira E, Paolini M, Contestabile A (April 2009). "Long-term dietary administration of valproic acid does not affect, while retinoic acid decreases, the lifespan of G93A mice, a model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". primary. Muscle & Nerve. 39 (4): 548–52. doi:10.1002/mus.21260. PMID 19296491. S2CID 26101773.

- Rouaux C, Panteleeva I, René F, Gonzalez de Aguilar JL, Echaniz-Laguna A, Dupuis L, Menger Y, Boutillier AL, Loeffler JP (May 2007). "Sodium valproate exerts neuroprotective effects in vivo through CREB-binding protein-dependent mechanisms but does not improve survival in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model". primary. The Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (21): 5535–45. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1139-07.2007. PMC 6672753. PMID 17522299.

- Brzustowicz LM, Lehner T, Castilla LH, Penchaszadeh GK, Wilhelmsen KC, Daniels R, Davies KE, Leppert M, Ziter F, Wood D (April 1990). "Genetic mapping of chronic childhood-onset spinal muscular atrophy to chromosome 5q11.2-13.3". primary. Nature. 344 (6266): 540–1. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..540B. doi:10.1038/344540a0. PMID 2320125. S2CID 4259327.

- Prior TW, Krainer AR, Hua Y, Swoboda KJ, Snyder PC, Bridgeman SJ, Burghes AH, Kissel JT (September 2009). "A positive modifier of spinal muscular atrophy in the SMN2 gene". primary. American Journal of Human Genetics. 85 (3): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.002. PMC 2771537. PMID 19716110.

- Schreml J, Riessland M, Paterno M, Garbes L, Roßbach K, Ackermann B, Krämer J, Somers E, Parson SH, Heller R, Berkessel A, Sterner-Kock A, Wirth B (June 2013). "Severe SMA mice show organ impairment that cannot be rescued by therapy with the HDACi JNJ-26481585". primary. European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (6): 643–52. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.222. PMC 3658191. PMID 23073311.

- Lazaridis, Konstantinos; Tzartos, Socrates J. (2020). "Autoantibody Specificities in Myasthenia Gravis; Implications for Improved Diagnostics and Therapeutics". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 212. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00212. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 7033452. PMID 32117321.

- Avidan, Nili; Le Panse, Rozen; Berrih-Aknin, Sonia; Miller, Ariel (2014-08-01). "Genetic basis of myasthenia gravis – A comprehensive review". Journal of Autoimmunity. Myasthenia Gravis: A Comprehensive Review. 52: 146–153. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2013.12.001. ISSN 0896-8411. PMID 24361103.

- "Myasthenia Gravis". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- Golfinopoulou, Rebecca; Papageorgiou, Louis; Efthimiadou, Aspasia; Bacopoulou, Flora; Chrousos, George P.; Eliopoulos, Elias; Vlachakis, Dimitrios (2021-07-01). "Clinical Genomic, phenotype and epigenetic insights into the pathology, autoimmunity and weight management of patients with Myasthenia Gravis (Review)". Molecular Medicine Reports. 24 (1): 1–9. doi:10.3892/mmr.2021.12151. ISSN 1791-2997. PMID 34225443. S2CID 235744938.

- Wang, Lin; Zhang, Lijuan (2020). "Emerging Roles of Dysregulated MicroRNAs in Myasthenia Gravis". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 14: 507. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00507. ISSN 1662-453X. PMC 7253668. PMID 32508584.

- Ströbel, Philipp; Rosenwald, Andreas; Beyersdorf, Niklas; Kerkau, Thomas; Elert, Olaf; Murumägi, Astrid; Sillanpää, Niko; Peterson, Pärt; Hummel, Vera; Rieckmann, Peter; Burek, Christof (2004). "Selective loss of regulatory T cells in thymomas". Annals of Neurology. 56 (6): 901–904. doi:10.1002/ana.20340. ISSN 0364-5134. PMID 15562414. S2CID 43398892.

- Cron, Mélanie A.; Maillard, Solène; Delisle, Fabien; Samson, Nolwenn; Truffault, Frédérique; Foti, Maria; Fadel, Elie; Guihaire, Julien; Berrih-Aknin, Sonia; Le Panse, Rozen (2018). "Analysis of microRNA expression in the thymus of Myasthenia Gravis patients opens new research avenues". Autoimmunity Reviews. 17 (6): 588–600. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.008. ISSN 1873-0183. PMID 29655674. S2CID 4882702.

- Liu, Xiao-Fang; Wang, Run-Qi; Hu, Bo; Luo, Meng-Chuan; Zeng, Qiu-Ming; Zhou, Hao; Huang, Kun; Dong, Xiao-Hua; Luo, Yue-Bei; Luo, Zhao-Hui; Yang, Huan (2016-03-01). "MiR-15a contributes abnormal immune response in myasthenia gravis by targeting CXCL10". Clinical Immunology. 164: 106–113. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2015.12.009. ISSN 1521-6616. PMID 26845678.

- Lu, Jiayin; Yan, Mei; Wang, Yuzhong; Zhang, Junmei; Yang, Huan; Tian, Fa-fa; Zhou, Wenbin; Zhang, Ning; Li, Jing (2013-10-25). "Altered expression of miR-146a in myasthenia gravis". Neuroscience Letters. 555: 85–90. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2013.09.014. ISSN 0304-3940. PMID 24036458. S2CID 5317928.

- Vanyushin, B. F. (2004). "Enzymatic DNA Methylation Is an Epigenetic Control for Genetic Functions of the Cell". Biochemistry (Moscow). 70 (5): 488–499. doi:10.1007/s10541-005-0143-y. PMID 15948703. S2CID 25973184.

- Fang, Ti-Kun; Yan, Cheng-Jun; Du, Juan (2018). "CTLA-4 methylation regulates the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis and the expression of related cytokines". Medicine. 97 (18): e0620. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010620. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC 6393147. PMID 29718870.

- Cron, Mélanie A.; Guillochon, Émilie; Kusner, Linda; Le Panse, Rozen (2020-06-10). "Role of miRNAs in Normal and Myasthenia Gravis Thymus". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 1074. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01074. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 7297979. PMID 32587589.

- Fang, Ti-Kun; Yan, Cheng-Jun; Du, Juan (2018). "CTLA-4 methylation regulates the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis and the expression of related cytokines". Medicine. 97 (18): e0620. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010620. ISSN 1536-5964. PMC 6393147. PMID 29718870.

- Xu, Si; Wang, Tianfeng; Lu, Xiaoyu; Zhang, Huixue; Liu, Li; Kong, Xiaotong; Li, Shuang; Wang, Xu; Gao, Hongyu; Wang, Jianjian; Wang, Lihua (2021). "Identification of LINC00173 in Myasthenia Gravis by Integration Analysis of Aberrantly Methylated- Differentially Expressed Genes and ceRNA Networks". Frontiers in Genetics. 12: 726751. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.726751. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 8481885. PMID 34603387.

- "HLA-DRB1 gene: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- De Waal Malefyt, R.; Abrams, J.; Bennett, B.; Figdor, C. G.; De Vries, J. E. (1991-11-01). "Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 174 (5): 1209–1220. doi:10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. ISSN 0022-1007. PMC 2119001. PMID 1940799.

- Fujii, Shin-ichiro; Shimizu, Kanako; Shimizu, Takashi; Lotze, Michael T. (2001-10-01). "Interleukin-10 promotes the maintenance of antitumor CD8+ T-cell effector function in situ". Blood. 98 (7): 2143–2151. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.7.2143. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 11568001.

- Punga, Anna Rostedt; Andersson, Mats; Alimohammadi, Mohammad; Punga, Tanel (2015-09-15). "Disease specific signature of circulating miR-150-5p and miR-21-5p in myasthenia gravis patients". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 356 (1): 90–96. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.06.019. ISSN 0022-510X. PMID 26095457. S2CID 9099858.

- Bennett DA, Yu L, Yang J, Srivastava GP, Aubin C, De Jager PL (January 2015). "Epigenomics of Alzheimer's disease". review. Translational Research. 165 (1): 200–20. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2014.05.006. PMC 4233194. PMID 24905038.

- Mastroeni D, McKee A, Grover A, Rogers J, Coleman PD (August 2009). "Epigenetic differences in cortical neurons from a pair of monozygotic twins discordant for Alzheimer's disease". primary. PLOS ONE. 4 (8): e6617. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6617M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006617. PMC 2719870. PMID 19672297.

- Chouliaras L, Mastroeni D, Delvaux E, Grover A, Kenis G, Hof PR, Steinbusch HW, Coleman PD, Rutten BP, van den Hove DL (September 2013). "Consistent decrease in global DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation in the hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease patients". primary. Neurobiology of Aging. 34 (9): 2091–9. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.021. PMC 3955118. PMID 23582657.

- Mastroeni D, Grover A, Delvaux E, Whiteside C, Coleman PD, Rogers J (December 2010). "Epigenetic changes in Alzheimer's disease: decrements in DNA methylation". primary. Neurobiology of Aging. 31 (12): 2025–37. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.12.005. PMC 2962691. PMID 19117641.