Esophageal atresia

Esophageal atresia is a congenital medical condition (birth defect) that affects the alimentary tract. It causes the esophagus to end in a blind-ended pouch rather than connecting normally to the stomach. It comprises a variety of congenital anatomic defects that are caused by an abnormal embryological development of the esophagus. It is characterized anatomically by a congenital obstruction of the esophagus with interruption of the continuity of the esophageal wall.[2]

| Esophageal atresia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Oesophageal atresia |

| |

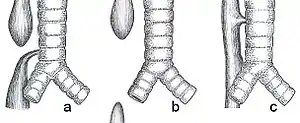

| Common anatomical types of esophageal atresia a) Esophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula (86%), Gross C. b) Isolated esophageal atresia without tracheoesophageal fistula (7%), Gross A. c) H-type tracheoesophageal fistula (4%), Gross E.[1] | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

Signs and symptoms

This birth defect arises in the fourth fetal week, when the trachea and esophagus should begin to separate from each other.[3]

It can be associated with disorders of the tracheoesophageal septum.[4]

Complications

Any attempt at feeding could cause aspiration pneumonia as the milk collects in the blind pouch and overflows into the trachea and lungs. Furthermore, a fistula between the lower esophagus and trachea may allow stomach acid to flow into the lungs and cause damage. Because of these dangers, the condition must be treated as soon as possible after birth.[5]

Associated birth defects

Other birth defects may co-exist, particularly in the heart, but sometimes also in the anus, spinal column, or kidneys. This is known as VACTERL association because of the involvement of Vertebral column, Anorectal, Cardiac, Tracheal, Esophageal, Renal, and Limbs. It is associated with polyhydramnios in the third trimester.[6]

Diagnosis

This condition may be visible, after about 26 weeks, on an ultrasound. On antenatal USG, the finding of an absent or small stomach in the setting of polyhydramnios was considered a potential symptom of esophageal atresia. However, these findings have a low positive predictive value. The upper neck pouch sign is another sign that helps in the antenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia and it may be detected soon after birth as the affected infant will be unable to swallow its own saliva.[7]

On plain X-ray, a feeding tube will not be seen pass through the esophagus and remain coiled in the upper oesophageal pouch.[8]

Classification

This condition takes several different forms, often involving one or more fistulas connecting the trachea to the esophagus (tracheoesophageal fistula).

| Gross[9] | Vogt[10] | Ladd[11] | Name(s) | Description | Frequency[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Type 1 | - | Esophageal Agenesis | Very rare complete absence of the esophagus, not included in classification by Gross or Ladd | N/A |

| Type A | Type 2 | I | "Long Gap", "Pure" or "Isolated" Esophageal Atresia | Characterized by the presence of a "gap" between the two esophageal blind pouches with no fistula present. | 7% |

| Type B | Type 3A | II | Esophageal Atresia with proximal TEF (tracheoesophageal fistula) | The upper esophageal pouch connects abnormally to the trachea. The lower esophageal pouch ends blindly. | 2-3% |

| Type C | Type 3B | III, IV | Esophageal Atresia with distal TEF (tracheoesophageal fistula) | The lower esophageal pouch connects abnormally to the trachea. The upper esophageal pouch ends blindly. | 86% |

| Type D | Type 3C | V | Esophageal Atresia with both proximal and distal TEFs (two tracheoesophageal fistulas) | Both the upper and lower esophageal pouch make an abnormal connection with the trachea in two separate, isolated places. | <1% |

| Type E | Type 4 | - | TEF (tracheoesophageal fistula) ONLY with no Esophageal Atresia, H-Type | Esophagus fully intact and capable of its normal functions, however, there is an abnormal connection between the esophagus and the trachea. Not included in classification by Ladd | 4% |

Treatment

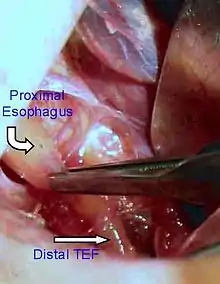

Treatments for the condition vary depending on its severity. The most immediate and effective treatment in the majority of cases is a surgical repair to close the fistula/s and reconnect the two ends of the esophagus to each other. Although this is usually done through an incision between the ribs on right side of the baby, a technique using three small incisions (thoracoscopy) is being used at some centers.[12]

In a minority of cases, the gap between upper and lower esophageal segments may be too long to bridge. In these situations traditional surgical approaches include gastrostomy followed by gastric pull-up, colonic transposition and jejunum transposition.[13] Gastric pull-up has been the preferred approach at many specialized centers, including Great Ormond Street (London) and Mott Children's Hospital (Ann Arbor).[14] Gastrostomy, or G-tube, allows for tube feedings into the stomach through the abdominal wall. Often a cervical esophagostomy will also be done, to allow the saliva which is swallowed to drain out a hole in the neck. Months or years later, the esophagus may be repaired, sometimes by using a segment of bowel brought up into the chest, interposing between the upper and lower segments of esophagus.[15]

In some of these so-called long gap cases, though, an advanced surgical treatment developed by John Foker, MD,[16] may be utilized to elongate and then join the short esophageal segments. Using the Foker technique, surgeons place traction sutures in the tiny esophageal ends and increase the tension on these sutures daily until the ends are close enough to be sewn together. The result is a normally functioning esophagus, virtually indistinguishable from one congenitally well formed. Unfortunately, the results have been somewhat difficult to replicate by other surgeons and the need for multiple operations has tempered enthusiasm for this approach. The optimal treatment in cases of long gap esophageal atresia remains controversial.[17]

Magnetic compression method is another method for repairing long-gap esophageal atresia. This method does not require replacing the missing section with grafts of the intestine or other body parts. Using electromagnetic force to attract the upper and lower ends of the esophagus together was first tried in the 1970s by using steel pellets attracted to each other by applying external electromagnets to the patient. In the 2000s a further refinement was developed by Mario Zaritzky's group and others.[18] The newer method uses permanent magnets and a balloon.

- The magnets are inserted into the upper pouch via the baby's mouth or nose, and the lower via the gastrotomy feeding tube hole (which would have had to be made anyway to feed the baby, therefore not requiring any additional surgery).

- The distance between the magnets is controlled by a balloon in the upper pouch, between the end of the pouch and the magnet. This also controls the force between the magnets so it is not strong enough to cause damage.

- After the ends of the esophagus have stretched enough to touch, the upper magnet is replaced by one without a balloon and the stronger magnetic attraction causes the ends to fuse (anastomosis).[19][20][21][22]

In April 2015 Annalise Dapo became the first patient in the United States to have their esophageal atresia corrected using magnets.[19][23]

Complications

Postoperative complications may include a leak at the site of closure of the esophagus. Sometimes a stricture, or tight spot, will develop in the esophagus, making it difficult to swallow. Esophageal stricture can usually be dilated using medical instruments. In later life, most children with this disorder will have some trouble with either swallowing or heartburn or both. Esophageal dismotility occurs in 75-100% of patients. After esophageal repair (anastomosis) the relative flaccidity of former proximal pouch (blind pouch, above) along with esophageal dysmotility can cause fluid buildup during feeding. Owing to proximity, pouch ballooning can cause tracheal occlusion. Severe hypoxia ("dying spells") follows and medical intervention can often be required.

Tracheomalacia a softening of the trachea, usually above the carina (carina of trachea), but sometimes extensive in the lower bronchial tree as well—is another possible serious complication. A variety of treatments for tracheomalacia associated with esophageal atresia are available. If not severe, the condition can be managed expectantly since the trachea will usually stiffen as the infant matures into the first year of life. When only the trachea above the carina is compromised, one of the "simplest" interventions is aortopexy wherein the aortic loop is attached to the rear of the sternum, thereby mechanically relieving pressure from the softened trachea. An even simpler intervention is stenting. However, epithelial cell proliferation and potential incorporation of the stent into the trachea can make subsequent removal dangerous.

The incidence of asthma, bronchitis, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and recurrent infections in adolescent and adult esophageal atresia survivors far exceeds that of their healthy peers.[24] During the first decade of surgical repair of EA, as much as 20% of patients died from pneumonia. From there on, pneumonia has remained as a major pulmonary complication and a reason for readmissions after repair of EA.[24][25] The risk factors of pneumonia within the first five years of life include other acute respiratory infections and high number of esophageal dilatations.[26]

Epidemiology

It occurs in approximately 1 in 3000 live births.[1]

Congenital esophageal atresia (EA) represents a failure of the esophagus to develop as a continuous passage. Instead, it ends as a blind pouch. Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) represents an abnormal opening between the trachea and esophagus. EA and TEF can occur separately or together. EA and TEF are diagnosed in the ICU at birth and treated immediately.

The presence of EA is suspected in an infant with excessive salivation (drooling) and in a newborn with drooling that is frequently accompanied by choking, coughing and sneezing. When fed, these infants swallow normally but begin to cough and struggle as the fluid returns through the nose and mouth. The infant may become cyanotic (turn bluish due to lack of oxygen) and may stop breathing as the overflow of fluid from the blind pouch is aspirated (sucked into) the trachea. The cyanosis is a result of laryngospasm (a protective mechanism that the body has to prevent aspiration into the trachea). Over time respiratory distress will develop.

If any of the above signs/symptoms are noticed, a catheter is gently passed into the esophagus to check for resistance. If resistance is noted, other studies will be done to confirm the diagnosis. A catheter can be inserted and will show up as white on a regular x-ray film to demonstrate the blind pouch ending. Sometimes a small amount of barium (chalk-like liquid) is placed through the mouth to diagnose the problems.

Treatment of EA and TEF is surgery to repair the defect. If EA or TEF is suspected, all oral feedings are stopped and intravenous fluids are started. The infant will be positioned to help drain secretions and decrease the likelihood of aspiration. Babies with EA may sometimes have other problems. Studies will be done to look at the heart, spine and kidneys. Surgery to repair EA is essential as the baby will not be able to feed and is highly likely to develop pneumonia. Once the baby is in condition for surgery, an incision is made on the side of the chest. The esophagus can usually be sewn together. Following surgery, the baby may be hospitalized for a variable length of time. Care for each infant is individualized. It's very commonly seen in a newborn with imperforate anus.

References

- Spitz L (May 2007). "Oesophageal atresia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2: 24. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-24. PMC 1884133. PMID 17498283.

- Edwards, Nicole A.; Shacham-Silverberg, Vered; Weitz, Leelah; Kingma, Paul S.; Shen, Yufeng; Wells, James M.; Chung, Wendy K.; Zorn, Aaron M. (2021). "Developmental basis of trachea-esophageal birth defects". Developmental biology. 477: 85–97. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2021.05.015. ISSN 0012-1606. PMC 8277759. PMID 34023332.

- CDC (2019-12-04). "Facts about Esophageal Atresia | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Clark DC (February 1999). "Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula". American Family Physician. 59 (4): 910–6, 919–20. PMID 10068713.

- "default - Stanford Medicine Children's Health". www.stanfordchildrens.org. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Yang, Lin; Li, Shu; Zhong, Lin; Qiu, Li; Xie, Liang; Chen, Lina (2019-10-18). "VACTERL association complicated with multiple airway abnormalities". Medicine. 98 (42): e17413. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000017413. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC 6824793. PMID 31626096.

- Garg, Mukesh Kumar (2009). "Case report: Upper neck pouch sign in the antenatal diagnosis of esophageal atresia". The Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging. 19 (3): 252–254. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.54875. ISSN 0971-3026. PMC 2766887. PMID 19881098.

- Higano NS, Bates AJ, Tkach JA, Fleck RJ, Lim FY, Woods JC, Kingma PS (February 2018). "Pre- and post-operative visualization of neonatal esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula via magnetic resonance imaging". Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 29: 5–8. doi:10.1016/j.epsc.2017.10.001. PMC 5794017. PMID 29399473.

- Gross RE (1953). The Surgery of Infancy and Childhood. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

- Vogt EC (November 1929). "Congenital esophageal atresia". American Journal of Roentgenology. 22: 463–465.

- Ladd WE (1944). "The surgical treatment of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistulas". The New England Journal of Medicine. 230 (21): 625–637. doi:10.1056/nejm194405252302101.

- Ke, Mingyao; Wu, Xuemei; Zeng, Junli (2015). "The treatment strategy for tracheoesophageal fistula". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 7 (Suppl 4): S389–S397. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.11. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4700364. PMID 26807286.

- "Esophageal Atresia Treatment Program". Children's Hospital Boston. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Hirschl RB, Yardeni D, Oldham K, Sherman N, Siplovich L, Gross E, et al. (October 2002). "Gastric transposition for esophageal replacement in children: experience with 41 consecutive cases with special emphasis on esophageal atresia". Annals of Surgery. 236 (4): 531–9, discussion 539–41. doi:10.1097/00000658-200210000-00016. PMC 1422608. PMID 12368682.

- Kaman, Lileswar; Iqbal, Javid; Kundil, Byju; Kochhar, Rakesh (2010). "Management of Esophageal Perforation in Adults". Gastroenterology Research. 3 (6): 235–244. doi:10.4021/gr263w. ISSN 1918-2805. PMC 5139851. PMID 27942303.

- "Esophageal atresia - symptoms, tests, Foker treatment". Children's Hospital Boston. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Kunisaki SM, Foker JE (June 2012). "Surgical advances in the fetus and neonate: esophageal atresia". Clinics in Perinatology. 39 (2): 349–61. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2012.04.007. PMID 22682384.

- "| Department of Radiology | The University of Chicago". radiology.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Mims B (10 April 2015). "Pioneering WakeMed procedure corrects infant's rare disorder". WRAL.com. Raleigh-Durham: Capitol Broadcasting.

- "Dr Zaritzky Pioneers Non-surgical Option for Babies with Esophageal Atresia". Department of Radiology. University of Chicago. 13 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

- Oehlerking A, Meredith JD, Smith IC, Nadeau PM, Gomez T, Trimble ZA, Mooney DP, Trumper DL (June 2011). "A hydraulically controlled nonoperative magnetic treatment for long gap esophageal atresia" (PDF). Journal of Medical Devices. 5 (2): 027511. doi:10.1115/1.3589828. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- Lovvorn III HN, Baron CM, Danko ME, Novotny NM, Bucher BT, Johnston KK, Zaritzky MF (2014). "Staged repair of esophageal atresia: Pouch approximation and catheter-based magnetic anastomosis". Journal of Pediatric Surgery Case Reports. 2 (4): 170–175. doi:10.1016/j.epsc.2014.03.004.

- "New, non-invasive procedure for infant at WakeMed is first of its kind in U.S." WTVD-TV. Raleigh-Durham. 10 April 2015.

- Sistonen S, Malmberg P, Malmström K, Haahtela T, Sarna S, Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP (November 2010). "Repaired oesophageal atresia: respiratory morbidity and pulmonary function in adults". The European Respiratory Journal. 36 (5): 1106–12. doi:10.1183/09031936.00153209. PMID 20351029.

- Louhimo I, Lindahl H (1983). "Esophageal atresia: primary results of 500 consecutively treated patients". J Pediatr Surg. 18 (3): 217–229. doi:10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80089-x. PMID 6875767.

- Nurminen P, Koivusalo A, Hukkinen M, Pakarinen M (December 2019). "Pneumonia after Repair of Esophageal Atresia-Incidence and Main Risk Factors". European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 29 (6): 504–509. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1675775. hdl:10138/300624. PMID 30469161. S2CID 53719974.

Further reading

- Harmon CM, Coran AG (1998). "Congenital Anomalies of the Esophagus". Pediatric Surgery (5th ed.). St Louis, KY: Elsevier Science Health Science Division. ISBN 0-8151-6518-8.