Tracheoesophageal fistula

A tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF, or TOF; see spelling differences) is an abnormal connection (fistula) between the esophagus and the trachea. TEF is a common congenital abnormality, but when occurring late in life is usually the sequela of surgical procedures such as a laryngectomy.

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Presentation

Tracheoesophageal fistula is suggested in a newborn by copious salivation associated with choking, coughing, vomiting, and cyanosis coincident with the onset of feeding. Esophageal atresia and the subsequent inability to swallow typically cause polyhydramnios in utero. Rarely it may present in an adult.[1]

Complications

Surgical repair can sometimes result in complications, including:

- Stricture, due to gastric acid erosion of the shortened esophagus

- Leak of contents at the point of anastomosis

- Recurrence of fistula

- Gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- Dysphagia

- Asthma-like symptoms, such as persistent coughing/wheezing

- Recurrent chest infections

- Tracheomalacia

Associations

Neonates with TEF or esophageal atresia are unable to feed properly. Once diagnosed, prompt surgery is required to allow the food intake.[2] Some children experience problems following TEF surgery; they can develop dysphagia and thoracic problems. Children with TEF can also be born with other abnormalities, most commonly those described in VACTERL association - a group of anomalies which often occur together, including heart, kidney and limb deformities. 6% of babies with TEF also have a laryngeal cleft.[3]

Cause

Congenital TEF can arise due to failed fusion of the tracheoesophageal ridges after the fourth week of embryological development.[4]

A fistula, from the Latin meaning 'a pipe', is an abnormal connection running either between two tubes or between a tube and a surface. In tracheo-esophageal fistula it runs between the trachea and the esophagus. This connection may or may not have a central cavity; if it does, then food within the esophagus may pass into the trachea (and on to the lungs) or alternatively, air in the trachea may cross into the esophagus.

TEF can also occur due to pressure necrosis by a tracheostomy tube in apposition to a nasogastric tube (NGT).[5]

Diagnosis

TEF should be suspected once the baby fails to swallow after their first feeding during the first day of life. Esophageal atresia can be diagnosed by Ryle nasogastric tube; if the Ryle fails to pass into the stomach, then this indicates esophageal atresia and loss of communication between stomach and esophagus. TEF may be diagnosed by MRI which clarifies the atretic esophagus (if presents) and TEF, as well as its location and anatomy. Gastrograffin contrast swallow should not be used if TEF is suspected, due to its high risk of allergy and severe intractable chest infection.

Classification

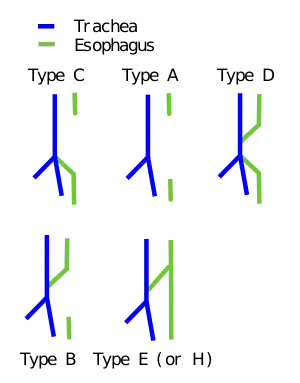

Fistulae between the trachea and esophagus in the newborn can be of diverse morphology and anatomical location.[6][7] However, various pediatric surgical publications have attempted a classification system based on the below specified types.

Not all types include both esophageal agenesis and tracheoesophageal fistula, but the most common types do.

| Gross | Vogt[8] | Description | EA? | TEF? |

| - | Type 1 | Esophageal agenesis. Very rare, and not included in the classification by Gross.[9] | Yes | No |

| Type A | Type 2 | Proximal and distal esophageal bud—a normal esophagus with a missing mid-segment. | Yes | No |

| Type B | Type 3A | Proximal esophageal termination on the lower trachea with distal esophageal bud. | Yes | Yes |

| Type C | Type 3B | Proximal esophageal atresia (esophagus continuous with the mouth ending in a blind loop superior to the sternal angle) with a distal esophagus arising from the lower trachea or carina. (Most common, up to 90% of cases.) | Yes | Yes |

| Type D | Type 3C | Proximal esophageal termination on the lower trachea or carina with distal esophagus arising from the carina. | Yes | Yes |

| Type E (or H-Type) | - | A variant of type D: if the two segments of esophagus communicate, this is sometimes termed an H-type fistula due to its resemblance to the letter H. TEF without EA. | No | Yes |

The letter codes are usually associated with the system used by Gross,[10] while number codes are usually associated with Vogt.[11]

An additional type, "blind upper segment only" has been described,[12] but this type is not usually included in most classifications. (For the purposes of this discussion, proximal esophagus indicates normal esophageal tissue arising normally from the pharynx, and distal esophagus indicates normal esophageal tissue emptying into the proximal stomach.)

Treatment

It is surgically corrected, with resection of any fistula and anastomosis of any discontinuous segments.[2] Babies often need to spend time in a neonatal intensive care unit for feeding with a stomach feeding tube.[2] Antibiotics, pain relief, a chest drain, oxygen, and ventilation may all be needed.[2]

References

- Newberry D., Sharma V., Reiff D., De Lorenzo F. (1999). "A "little cough" for 40 years". Lancet. 354 (9185): 1174. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)10014-x. PMID 10513712. S2CID 39432557.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Oesophageal atresia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula". nhs.uk. 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Bluestone, Charles D. (2003). Pediatric otolaryngology, Volume 2. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1468. ISBN 0-7216-9197-8.

- Clark DC (February 1999). "Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula". American Family Physician. 59 (4): 910–6, 919–20. PMID 10068713.

- Dr. Lorne H. Blackbourne, Advanced Surgical Recall, 3rd Ed., pg. 206.

- Spitz L (2007). "Oesophageal atresia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-24. PMC 1884133. PMID 17498283.

- Kovesi T, Rubin S (2004). "Long-term complications of congenital esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula". Chest. 126 (3): 915–25. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.915. PMID 15364774.

- "Long-term Complications of Congenital Esophageal Atresia and/or Tracheoesophageal Fistula -- Kovesi and Rubin 126 (3): 915 Figure 1 -- Chest". Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- P. Puri (2005). M. E. Höllwarth (ed.). Pediatric Surgery (Springer Surgery Atlas Series). Berlin: Springer. p. 30. ISBN 3-540-40738-3.

- Gross, RE. The surgery of infancy and childhood. Philadelphia, WB Saunders; 1953.

- Vogt EC. Congenital esophageal atresia. Am J of Roentgenol. 1929;22:463–465.

- Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 800. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.