Foreskin restoration

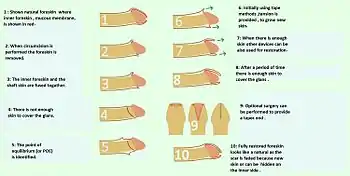

Foreskin restoration is the process of expanding the skin on the penis to reconstruct an organ similar to the foreskin, which has been removed by circumcision or injury. Foreskin restoration is primarily accomplished by stretching the residual skin of the penis, but surgical methods also exist. Restoration creates a facsimile of the foreskin, but specialized tissues removed during circumcision cannot be reclaimed. Actual regeneration of the foreskin is experimental at this time. Some forms of restoration involve only partial regeneration in instances of a high-cut wherein the circumcisee feels that the circumciser removed too much skin and that there is not enough skin for erections to be comfortable.[1]

_applied.jpg.webp)

History

In the Greco-Roman world intact genitals, including the foreskin, were considered a sign of beauty, civility, and masculinity.[2] In Classical Greek and Roman societies (8th century BC to 6th century AD), exposure of the glans was considered disgusting and improper, and did not conform to the Hellenistic ideal of gymnastic nudity.[2] Men with short foreskins would wear the kynodesme to prevent exposure.[3] As a consequence of this social stigma, an early form of foreskin restoration known as epispasm was practiced among some Jews in Ancient Rome (8th century BC to 5th century AD).[4]

Foreskin restoration is of ancient origin and dates back to the reign of the Roman Emperor Tiberius (AD 14-37), when surgical means were taken to lengthen the foreskin of individuals born with either a short foreskin that did not cover the glans completely[2] or a completely exposed glans as a result of circumcision.[5] Again, during World War II some European Jews sought foreskin restoration to avoid Nazi persecution.[6]

Non-surgical techniques

Tissue expansion

Non-surgical foreskin restoration, accomplished through tissue expansion, is the more commonly used method.[7]

Tissue expansion has long been known to stimulate mitosis, and research shows that regenerated human tissues have the attributes of the original tissue.[8]

Methods and devices

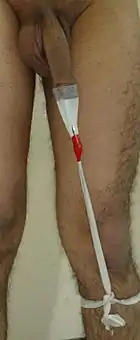

During restoration via tissue expansion, the remaining penile skin is pulled forward over the glans, and tension is maintained either manually or through the aid of a foreskin restoration device.[9]

Many specialized foreskin restoration devices that grip the skin with or without tape are also commercially available. Tension from these devices may be applied by weights, elastic straps, or inflation as a means to either push the skin forward on the penis, or by a combination of these methods.

Surgical techniques

Foreskin reconstruction

Surgical methods of foreskin restoration, known as foreskin reconstruction, usually involve a method of grafting skin onto the distal portion of the penile shaft. The grafted skin is typically taken from the scrotum, which contains the same smooth muscle (known as dartos fascia) as does the skin of the penis. One method involves a four-stage procedure in which the penile shaft is buried in the scrotum for a period of time.[10] Such techniques are costly, and have the potential to produce unsatisfactory results or serious complications related to the skin graft. The frenulum can also be reconstructed.[11]

British Columbia resident Paul Tinari was held down and circumcised at the age of eight in what he stated was "a routine form of punishment" for masturbation at residential schools. Following a lawsuit Tinari's surgical foreskin restoration was covered by the British Columbia Ministry of Health. The plastic surgeon who performed the restoration was the first in Canada to have done such an operation, and used a technique similar to that described above.[12][13]

Results

Time required

The amount of time required to restore a foreskin using non-surgical methods depends on the amount of skin present at the start of the process, the subject's degree of commitment, the techniques used, the body's natural degree of plasticity, and the length of foreskin the individual desires.

The results of surgical restoration are immediate, but often described as unsatisfactory and most restoration groups advise against surgery.

Physical aspects

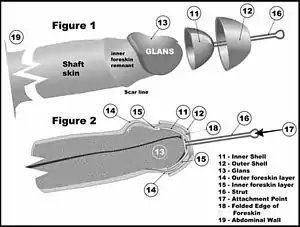

Restoration creates a facsimile of the prepuce, but specialized tissues removed during circumcision cannot be reclaimed. Surgical procedures exist to reduce the size of the opening once restoration is complete (as depicted in the image above),[14] or it can be alleviated through a longer commitment to the skin expansion regime to allow more skin to collect at the tip.

The natural foreskin is composed of smooth dartos muscle tissue (called the peripenic muscle[15]), large blood vessels, extensive innervation, outer skin, and inner mucosa.[16]

The natural foreskin has three principal components, in addition to blood vessels, nerves, and connective tissue: skin, which is exposed exteriorly; mucous membrane, which is the surface in contact with the glans penis when the penis is flaccid; and a band of muscle within the tip of the foreskin. Generally, the skin grows more readily in response to stretching than does the mucous membrane. The ring of muscle which normally holds the foreskin closed is completely removed in the majority of circumcisions and cannot be regrown, so the covering resulting from stretching techniques is usually looser than that of a natural foreskin. Nonetheless, according to some observers, it is difficult to distinguish a restored foreskin from a natural foreskin because restoration produces a "nearly normal-appearing prepuce".[17]

The process of foreskin restoration seeks to regenerate some of the tissue removed by circumcision, as well as provide coverage of the glans. According to research, the foreskin comprises over half of the skin and mucosa of the human penis.[18]

In some men, foreskin restoration may alleviate certain problems they attribute to their circumcision. Such problems include prominent scarring (33%), insufficient penile skin for comfortable erection (27%), erectile curvature from uneven skin loss (16%), and pain and bleeding upon erection/manipulation (17%). The poll also asked about awareness of or involvement in foreskin restoration and included an open comment section. Many respondents and their wives "reported that restoration resolved the unnatural dryness of the circumcised penis, which caused abrasion, pain or bleeding during intercourse, and that restoration offered unique pleasures, which enhanced sexual intimacy."[19] One man reported he had a great loss of sensation in the glans because his foreskin was not present.[20]

Emotional, psychological and psychiatric aspects

Foreskin restoration has been reported as having beneficial emotional results in some men, and has been proposed as a treatment for negative feelings in some adult men about their infant circumcisions that someone else decided to have performed on them.[10][17][21][22]

Organizations

Various groups have been founded since the late 20th century, especially in North America where circumcision has been routinely performed on infants. In 1989, the National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM) was founded as a non-profit support group for men undertaking foreskin restoration. In 1991, the group UNCircumcising Information and Resource Centers (UNCIRC) was formed,[23] which was incorporated into NORM in 1994.[24] NORM chapters have been founded throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany. In France, there are two associations about this. The "Association contre la Mutilation des Enfants" AME (association against child mutilation), and more recently "Droit au Corps" (right to the body).[25]

See also

- Circumcision controversies

- Regeneration in humans

- Restoration device

- Tissue expansion

References

- Lerman SE, Liao JC (December 2001). "Neonatal circumcision". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 48 (6): 1539–57. doi:10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70390-4. PMID 11732129.

-

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

— Jacob Neusner, Approaches to Ancient Judaism, New Series: Religious and Theological Studies (1993), p. 149, Scholars Press. - Hodges FM (2001). "The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Johns Hopkins University Press. 75 (3): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193.

- Rubin JP (July 1980). "Celsus' decircumcision operation: medical and historical implications". Urology. 16 (1): 121–4. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325.

- Money J (1991). "Sexology, body image, foreskin restoration, and bisexual status". Journal of Sex Research. Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality. 28 (1): 145–56. doi:10.1080/00224499109551600.

- Tushmet L (1965). "Uncircumcision". Medical Times. 93 (6): 588–93. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23.

- Collier R (December 2011). "Whole again: the practice of foreskin restoration". CMAJ. 183 (18): 2092–3. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4009. PMC 3255154. PMID 22083672.

- Cordes S, Calhoun KH, Quinn FB (1997-10-15). "Tissue Expanders". University of Texas Medical Branch Department of Otolaryngology Grand Rounds. Archived from the original on 2004-10-11.

- Goodwin, Willard E. (1990-11-01). "Uncircumcision: A Technique for Plastic Reconstruction of a Prepuce after Circumcision". Journal of Urology. 144 (5): 1203–1205. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39693-3. PMID 2231896.

- Greer Jr DM, Mohl PC, Sheley KA (2010). "A technique for foreskin reconstruction and some preliminary results". The Journal of Sex Research. 18 (4): 324–30. doi:10.1080/00224498209551158. JSTOR 3812166.

- Song B, Hou ZH, Liu QL, Qian WP (February 2015). "[Penile frenulum lengthening for premature ejaculation]". Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue = National Journal of Andrology (in Chinese). 21 (2): 149–52. PMID 25796689.

- Euringer A (2006-07-25). "BC Health Pays to Restore Man's Foreskin". The Tyee.

- Laliberté J (2006). "BC man's foreskin op a success". Natl Rev Med. 3 (12). Archived from the original on 2006-08-15.

- Griffith RW (1992). "Finishing Touches to the Foreskin". In Bigelow J (ed.). The Joy of Uncircumcising! (1998 ed.). pp. 188–192. ISBN 0-9630482-1-X.

- Jefferson G (1916). "The peripenic muscle: some observations on the anatomy of phimosis". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 23: 177–81.

- Cold CJ, Taylor JR (January 1999). "The prepuce". BJU International. 83 (Suppl 1): 34–44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. PMID 10349413. S2CID 30559310.

- Goodwin WE (November 1990). "Uncircumcision: a technique for plastic reconstruction of a prepuce after circumcision". The Journal of Urology. 144 (5): 1203–5. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39693-3. PMID 2231896.

- Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ (February 1996). "The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision". British Journal of Urology. 77 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.1996.85023.x. PMID 8800902.

- Hammond T (January 1999). "A preliminary poll of men circumcised in infancy or childhood". BJU International. 83 (Suppl 1): 85–92. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1085.x. PMID 10349419. S2CID 13397416.

- Kirby RS (1994). "The Joy of Uncircumcising! Restore Your Birthright and Maximize Sexual Pleasure". BMJ. 309 (6955): 676–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6955.679a. PMC 2541521.

- Penn J (July 1963). "PENILE REFORM". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 16: 287–8. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(63)80123-X. PMID 14042759.

- Boyle GJ, Goldman R, Svoboda JS, Fernandez E (May 2002). "Male circumcision: pain, trauma and psychosexual sequelae". Journal of Health Psychology. 7 (3): 329–43. doi:10.1177/135910530200700310. PMID 22114254. S2CID 22036469.

- Bigelow J (Summer 1994). "Uncircumcising: undoing the effects of an ancient practice in a modern world". Mothering: 36–60.

- Griffiths RW. "NORM - History". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- "Qui sommes-nous?". Droit au Corps. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

Further reading

- Griffin GM (1992). Decircumcision: Foreskin Restoration, Methods and Circumcision Practices. Los Angeles: Added Dimensions Publishing. ISBN 1-879967-05-7.

- Bigelow J (1992). The Joy of Uncircumcising!: Exploring Circumcision: History, Myths, Psychology, Restoration, Sexual Pleasure, and Human Rights. Aptos, California: Hourglass Book Publishing. ISBN 0-9630482-1-X. (foreword by James L. Snyder)

- Payne RM, Fryer L (March 2001). "My responses to a few Frequently Asked Questions about Non-Surgical Foreskin Restoration" (PDF).

- Brandes SB, McAninch JW (January 1999). "Surgical methods of restoring the prepuce: a critical review". BJU International. 83 (Suppl. 1): 109–13. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1109.x. PMID 10349422.

- Schultheiss D, Truss MC, Stief CG, Jonas U (June 1998). "Uncircumcision: a historical review of preputial restoration". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 101 (7): 1990–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-199806000-00037. PMID 9623850.