HIV/AIDS in the United States

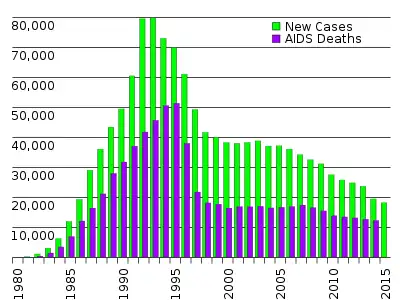

The AIDS epidemic, caused by HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus), found its way to the United States between the 1970s and 1980s,[2] but was first noticed after doctors discovered clusters of Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia in homosexual men in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco in 1981.[2][3] Treatment of HIV/AIDS is primarily via the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs, and education programs to help people avoid infection.[2]

Initially, infected foreign nationals were turned back at the United States border to help prevent additional infections.[4][5] The number of United States deaths from AIDS has declined sharply since the early years of the disease's presentation domestically. In the United States in 2016, 1.1 million people aged over 13 lived with an HIV infection, of whom 14% were unaware of their infection.[1] Gay and bisexual men, African Americans, and Latino Americans remain disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS in the United States.[1]

Mortality and morbidity

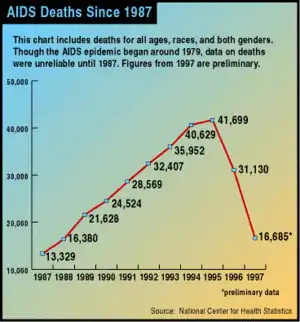

As of 2018, about 700,000 people have died of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, and nearly 13,000 people with AIDS in the United States die each year.[6]

With improved treatments and better prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, death rates have significantly declined.[7]

The overall death rate among persons diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in New York City decreased by sixty-two percent from 2001 to 2012.[8]

Containment

After the HIV/AIDS outbreak in the 1980s, various responses emerged in an effort to alleviate the issue.[9] These included new medical treatments,[10] travel restrictions,[11] and new public health policies[12] in the United States.

Medical treatment

Great progress was made in the U.S. following the introduction of three-drug anti-HIV treatments ("cocktails") that included antiretroviral drugs. David Ho, a pioneer of this approach, was honored as Time Magazine Man of the Year for 1996. Deaths were rapidly reduced by more than half, with a small but welcome reduction in the yearly rate of new HIV infections. Since this time, AIDS deaths have continued to decline, but much more slowly, and not as completely in Black Americans as in other population segments.[13][14]

Travel restrictions

In 1987, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) included HIV in its list of “communicable diseases of public health significance,” denying immigrants and short term foreign visits from anyone who tested positive for the virus.[15][4] In 1993, the US Congress passed the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, removing the HHS’ authority to dictate HIV as a “public health significance,” and explicitly including HIV as a cause for denying immigrants and foreign visitors entry into the US.[5][16] Anyone seeking US citizenship during the HIV ban was required to undergo a medical exam during the legalization process - testing positive would permanently deny the applicant entry into the country.[17] The law extended to include medication, where foreign travelers could be arrested for having antiretroviral drugs in their carry-on luggage. A famous example was in 1989, when a Dutch traveler to Minnesota was arrested for “several days” because he was carrying AZT in his luggage.[5]

During the turn of the 21st century, people who were HIV positive and seeking temporary visas or vacationing to the US had to avoid revealing their status on application forms, and either plan for their medication to be sent to the US or stop taking their medication.[18] Eventually the US began offering temporary admission waivers for people who were HIV positive. As stated in an interoffice memorandum in 2004, foreign nationals who were HIV positive could qualify for the waiver for either humanitarian/public interest reasons, or being “attendees of certain designated international events held in the United States”.[19]

In early December 2006, President George W. Bush indicated that he would issue an executive order allowing HIV positive people to enter the United States on standard visas. It was unclear whether applicants would still have to declare their HIV status.[20] However, the ban remained in effect throughout Bush's presidency.

In August 2007, Congresswoman Barbara Lee of California introduced H.R. 3337, the HIV Nondiscrimination in Travel and Immigration Act of 2007. This bill allowed travelers and immigrants entry to the United States without having to disclose their HIV status. The bill died at the end of the 110th Congress.[21]

In July 2008, President George W. Bush signed H.R. 5501 that lifted the ban in statutory law. However, the United States Department of Health and Human Services still held the ban in administrative (written regulation) law. New impetus was added to repeal efforts when Paul Thorn, a UK tuberculosis expert who was invited to speak at the 2009 Pacific Health Summit in Seattle, was denied a visa due to his HIV positive status. A letter written by Mr. Thorn, and read in his place at the Summit, was obtained by Congressman Jim McDermott, who advocated the issue to the Obama administration's Health Secretary.[21]

On October 30, 2009, President Barack Obama reauthorized the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Bill which expanded care and treatment through federal funding to nearly half a million.[22] The Department of Health and Human Services also crafted regulation that would end the HIV Travel and Immigration Ban, effective in January 2010.[22] On January 4, 2010, the United States Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention removed HIV infection from the list of "communicable diseases of public health significance," due to its not being spread by casual contact, air, food or water, and removed HIV status as a factor to be considered in the granting of travel visas, disallowing HIV status from among the diseases that could prevent people who were not U.S. citizens from entering the country.[23]

Public health policies

Since the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, several U.S. presidents have attempted to implement a national plan to control the issue. In 1987, Ronald Reagan created a Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic. This commission was recruited to investigate what steps are necessary for responding to the HIV/AIDS outbreak in the country, and the consensus was to establish more HIV testing, focus on prevention and treatment as well as expanding HIV care throughout the United States.[24] However, these changes were not implemented during this time, and the commission recommendations were largely ignored.

Another attempt to respond to the HIV/AIDS outbreak took place in 1996, when Bill Clinton established the National AIDS Strategy, which aimed to reduce number of infections, enhance research on HIV treatment, increase access to resources for people affected by AIDS, and also alleviate the racial disparities in HIV treatment and care.[25] Similarly to Reagan's plan, the National AIDS Strategy was not successfully enforced, providing only objectives without a specific action plan for implementation.

In 2010, Barack Obama created the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States (NHAS), with its three main objectives being to reduce the annual number of HIV infections, reduce health disparities, and increase access to resources and HIV care.[24] However, this new strategy differs in that it includes an Implementation Plan, with a timeline for achieving each of the three goals, as well as a document outlining the specific action plan that will be used.[26]

In 2019, Donald Trump announced a plan in his State of the Union Address to stop new HIV infections in the United States by 2030, though critics pointed to the President's policies reducing access to health insurance, anti-immigrant and anti-transgender policies as undermining this goal.[27] The Department of Health and Human Services issued grants to 32 HIV "hotspots" in 2019, and Congress earmarked over $291 million for the president's plan in FY2020.[28]

In 2022, a federal judge ruled that the U.S. military could not discharge personnel nor bar them from becoming officers on the basis of HIV status.[29]

Public perception

During the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, LGBTQ communities were further stigmatized as they became the focus of mass hysteria, suffered isolation and marginalization, and were targeted with extreme acts of violence in the United States.[32] One of the best known works on the history of HIV/AIDS is the 1987 book And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts, which contends that Ronald Reagan's administration dragged its feet in dealing with the crisis due to homophobia, while the gay community viewed early reports and public health measures with corresponding distrust, thus allowing the disease to spread further and infect hundreds of thousands more. This resulted in the formation of ACT-UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power by Larry Kramer. Galvanized by the U.S. federal government's inactivity, the movement led by AIDS activists to gain funding for AIDS research, which on a per-patient basis out-paced funding for more prevalent diseases such as cancer and heart disease, was used as a model for future lobbying for health research funding. [33]

The Shilts work popularized the misconception that the disease was introduced by a gay flight attendant named Gaëtan Dugas, referred to as "Patient Zero," although the author did not actually make this claim in the book. However, subsequent research has revealed that there were cases of AIDS much earlier than initially known. HIV-infected blood samples have been found from as early as 1959 in Africa (see HIV main entry), and HIV has been shown to have caused the 1969 death of Robert Rayford, a 16-year-old St. Louis male, who could have contracted it as early as 7 years old due to sexual abuse, suggesting that HIV had been present, at very low prevalence, in the U.S. since before the 1970s.

An early theory asserted that a series of inoculations against hepatitis B that were performed in the gay community of San Francisco were tainted with HIV. Although there was a high correlation between recipients of that vaccination and initial cases of AIDS, this theory has long been discredited. However, the theory has never been officially proven or disproven. HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are bloodborne diseases with very similar modes of transmission, and those at risk for one are at risk for the others.[34]

Activists and critics of current AIDS policies allege that another preventable impediment to stemming the spread of the disease and/or finding a treatment was the vanity of "celebrity" scientists. Robert Gallo, an American scientist involved in the search for a new virus in the people affected by the disease, became embroiled in a legal battle with French scientist Luc Montagnier, who had first discovered such a virus in tissue cultures derived from a patient suffering from enlargement of the lymphnodes (an early sign of AIDS). Montagnier had named the new virus LAV (Lymphoadenopathy-Associated Virus).

Gallo, who appeared to question the primacy of the French scientist's discovery, refused to recognize the "French virus" as the cause of AIDS, and tried instead to claim the disease was caused by a new member of a retrovirus family, HTLV, which he had discovered. Critics claim that because some scientists were more interested in trying to win a Nobel prize than in helping patients, research progress was delayed and more people needlessly died. After a number of meetings and high-level political intervention, the French scientists and Gallo agreed to "share" the discovery of HIV, although eventually Montagnier and his group were recognized as the true discoverers, and won the 2008 Nobel Prize for it.

Publicity campaigns were started in attempts to counter the incorrect and often vitriolic perception of AIDS as a "gay plague". These included the Ryan White case, red ribbon campaigns, celebrity dinners, the 1993 film version of And the Band Played On, sex education programs in schools, and television advertisements. Announcements by various celebrities that they had contracted HIV (including actor Rock Hudson, basketball star Magic Johnson, tennis player Arthur Ashe and singer Freddie Mercury) were significant in arousing media attention and making the general public aware of the dangers of the disease to people of all sexual orientations.[35]

Perspective of doctors

AIDS was met with great fear and concern by the nation, much like any other epidemic, and those who were primarily affected were homosexuals, African-Americans, Latinos, and intravenous drug users. The general thought of the population was to create distance and establish boundaries from these people, and some doctors were not immune from such impulses. During the epidemic, doctors began to not treat AIDS patients, not only to create distance from these groups of people, but also because they were afraid to contract the disease themselves. A surgeon in Milwaukee stated, "I've got to be selfish. It's an incurable disease that's uniformly fatal, and I'm constantly at risk for getting it. I've got to think about myself. I've got to think about my family. That responsibility is greater than to the patient."[36]

Some doctors thought it was their duty to stay away from the virus because they had other patients to think of. In a survey of doctors in the mid to late 1980s, a substantial number of physicians indicated that they didn't have an ethical obligation to treat and care for those patients with HIV/AIDS.[37] A study of primary care providers showed that half would not care for patients if they were given a choice.[38] In 1990, a national survey of doctors showed that "only 24% believed that office-based practitioners should be legally required to provide care to individuals with HIV infection."[36] However, there were many doctors who chose to care for these patients with AIDS for different reasons: they shared the same sexual orientation as the infected, a commitment to providing care to the diseased, an interest in the mysteries of infectious disease, or a desire to tame the awful threat.[36] Treating patients infected with the AIDS virus changed some doctors' personal lives, as it caused them to have to deal with some of the same stigmas that their patients had. This disease also weighed on their minds, because they often had to deal with witnessing the death of patients and most often those patients were as young or even younger than they were.

By race/ethnicity

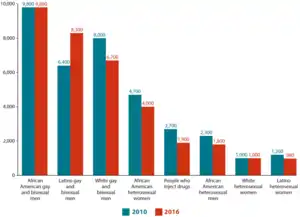

African Americans continue to experience the most severe burden of HIV, compared with other races and ethnicities. They represent approximately 13% of the U.S. population, but accounted for an estimated 43% of new HIV infections in 2017.[39] Furthermore, they make up nearly 52% of AIDS-related deaths in America. While the overall rates of HIV incidences and prevalence have decreased, they have increased in one particular demographic: African American gay and bisexual men (a 4% increase). In America, Black households were reported to have the lowest median income, leading to lower rates of individuals with health insurance. This creates cost barriers to antiretroviral treatments. The racial disparities between women afflicted with HIV/AIDS have been made clear in a 2010 study as well, which showed that 64% of women infected with HIV that year were Black women.[40] The trend is longstanding: CDC data from 2006 revealed that about half of the 1 million Americans living with HIV were Black.[41] This unequal distribution has led researchers to studying the long-term effects of racial and gender discrimination along with HIV-related stigma, and how this plays a role in people's lives. In 2019, Black and African American and Multiracial populations experienced the highest reported homelessness rates of any other racial group diagnosed with HIV.[42]

Hispanic/Latinx populations are also disproportionately affected by HIV. Hispanics/Latinos represented 16% of the population but accounted for 21% of new HIV infections in 2010. This disparity is even more apparent among Latina women, which represent 13% of the population but account for 20% of reported HIV cases among women in the United States.[43] Hispanics/Latinos accounted for 20% of people living with HIV infection in 2011. Disparities persist in the estimated rate of new HIV infections in Hispanics/Latinos. In 2010, the rate of new HIV infections for Latino males was 2.9 times that for white males, and the rate of new infections for Latinas was 4.2 times that for white females. Since the epidemic began, more than 100,888 Hispanics/Latinos with an AIDS diagnosis have died, including 2,863 in 2016.[44]

American Indian/Alaskan Native communities in the United States see a higher rate of HIV/AIDS in comparison to whites, Asians, and Native Hawaiians/other Native Pacific Islanders. Although AI/AN with HIV/AIDS only represent roughly 1% of positive cases in the U.S.,[45] the number of diagnoses among AI/AN gay and bisexual men rose by 54% between 2011 and 2015. Additionally, the survival rate of diagnosed AI/AN was the lowest of all races in the United States between 1998 and 2005.[46] In recent years, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have put in place a "high impact prevention approach"[47] in partnership with the Indian Health Service and the CDC Tribal Advisory Committee to tackle the growing rates in a culturally appropriate way. The higher rate of HIV/AIDS cases among AI/AN people have been attributed to a number of factors including socioeconomic disadvantages faced by AI/AN communities, which may result in difficulty accessing healthcare and high-quality housing. It may be more difficult for gay and bisexual AI/AN men to access healthcare due to living in rural communities, or due to stigma attached to their sexualities. AI/AN people have been reported to have higher rates of other STIs, including chlamydia and gonorrhea, which also increases likeliness of contracting or transmitting HIV.[48] Furthermore, as there are over 560 federally recognized AI/AN tribes, there is some difficulty in creating outreach programs which effectively appeal to all tribes whilst remaining culturally appropriate. As well as fear of stigma from within AI/AN communities, there may also be a fear among LGBTQ+ AI/AN of a lack of understanding from health professionals in the United States, particularly among Two Spirit people. A 2013 NASTAD report calls for the inclusion of LGBT and Two Spirit AI/AN in HIV/AID program planning and asserts that "health departments should utilize local experts to better understand regional definitions of "Two Spirit" and incorporate modules on Native gay men and Two Spirit people into cultural sensitivity courses for public health service providers".[49]

HIV/AIDS Racial Disparities in the U.S.

Health varies greatly by race and ethnicity demonstrating the long lasting impacts of historical and present day systemic racism in the U.S. The HIV/AIDS field is no exception to this. While there is no cure for HIV as of yet, prevention methods and access to medical care are major ways to know one's HIV status, become virally undetectable, and prevent transmission of HIV. There are prevention methods to help reduce HIV rates in the U.S. but these methods are not equally available or accessed. One prevention method is PrEP which is an intervention taken orally or an injection that prevents HIV. According to the CDC, Pre-exposure prophlyaxis or PrEP usage rates varied significantly by reported race and ethnicity in 2019. [50] For example, out of all the total number of individuals on PrEP, 63% of them identified as White, 8% identified as Black or African American, 14% identified as Hispanic/Latinx, and 9% identified as other. [50]

Additionally, healthcare access varies greatly by race and ethnicity in the U.S. Out of those living with HIV who received care only 63% of American Indian/Alaska Native people, 61% of Black/African American people, 65% of Hispanic/Latinx people, and 85% of Native Hawaiian and other pacific Islander people were virally suppressed in 2019. [42] This is in comparison to 71% of White people who were virally suppressed in 2019 according to the CDC. [50] Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and Multiracial populations were significantly more likely to miss at least one medical appointment in the past year compared with White populations.[42] Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and Multiracial populations that were diagnosed with HIV in the U.S. in 2019 all experienced higher need of dental care, SNAP or WIC benefits, shelter or housing services, and/or mental health services than White populations according to the CDC. [42]

National HIV/AIDs Strategy

The 2022-2025 National HIV/AIDs Strategy "recognizes racism as a serious public health threat that drives and affects both HIV outcomes and disparities" and while every part of the U.S. is threatened with HIV, "certain populations bear most of the burden signaling where our HIV prevention, care, and treatment efforts must be focused." [51] The 2022-2025 National HIV/AIDS strategy focuses on five priority populations including: gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, in particular, Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native men; Black women; transgender women; youth aged 13-24 years; and people who inject drugs. [51]

"Down-low" subculture among Black MSM

Down-low is an African-American slang term[52] specifically used within the African-American community that typically refers to a sexual subculture of Black men who usually identify as heterosexual but actively seek sexual encounters and relations with other men, practice gay cruising, and frequently adopt a specific hip-hop attire during these activities.[53][54] They generally avoid disclosing their same-sex sexual activities, and often have female sexual partner(s), and may be married or single.[55][56][57][58]

According to a study published in the Journal of Bisexuality, "[t]he Down Low is a lifestyle predominately practiced by young, urban Black men who have sex with other men and women, yet do not identify as gay or bisexual".[59]

In this context, "being on the down-low" is more than just men having sex with men in secret, or a variant of closeted homosexuality or bisexuality—it is a sexual identity that is, at least partly, defined by its "cult of masculinity" and its rejection of what is perceived as White American culture (including what is perceived as White American LGBT culture) and terms.[56][60][61][62] A 2003 cover story in The New York Times Magazine on the down-low phenomenon explains that the American Black community sees "homosexuality as a white man's perversion."[60] It then goes on to describe the down-low subculture as follows:

Rejecting a gay culture they perceive as white and effeminate, many black men have settled on a new identity, with its own vocabulary and customs and its own name: Down Low. There have always been men – black and white – who have had secret sexual lives with men. But the creation of an organized, underground subculture largely made up of black men who otherwise live straight lives is a phenomenon of the last decade. ... Most date or marry women and engage sexually with men they meet only in anonymous settings like bathhouses and parks or through the Internet. Many of these men are young and from the inner city, where they live in a hypermasculine thug culture. Other DL men form romantic relationships with men and may even be peripheral participants in mainstream gay culture, all unknown to their colleagues and families. Most DL men identify themselves not as gay or bisexual but first and foremost as black. To them, as to many blacks, that equates to being inherently masculine.[60]

The CDC cited three findings that relate to African-American men who operate on the down-low (engage in MSM activity but don't disclose to others):

- African American men who have sex with men (MSM), but who do not disclose their sexual orientation (nondisclosers), have a high prevalence of HIV infection (14%); nearly three times higher than nondisclosing MSMs of other races/ethnicities (5%).

- Confirming previous research, the study of 5,589 MSM, aged 15–29 years, in six U.S. cities found that African American MSM were more likely not to disclose their sexual orientation compared with white MSM (18% vs. 8%).

- HIV-infected nondisclosers were less likely to know their HIV status (98% were unaware of their infection compared with 75% of HIV-positive disclosers), and more likely to have had recent female sex partners.[63]

Risk factors contributing to the Black HIV rate

Access to healthcare is very important in preventing and treating HIV/AIDS. It can be affected by health insurance which is available to people through private insurers, Medicare and Medicaid which leaves some people still vulnerable. Historically, African-Americans have faced discrimination when it comes to receiving healthcare.[64]

Homosexuality is viewed negatively in the African-American Community. "In a qualitative study of 745 racially and ethnic diverse undergraduates attending a large Midwestern university, Calzo and Ward (2009) determined that parents of African-American participants discussed homosexuality more frequently than the parents of other respondents. In analyses of the values communicated, Calzo and Ward (2009) reported that Black parents offered greater indication that homosexuality is perverse and unnatural".[65]

Homosexuality is seen as a threat to the African-American empowerment.[66] Masculinity is seen as important for the African-American community because it shows that the community is in control of their own destiny. Since the stigma circling homosexuality is that it is "effeminate", then homosexuality is seen as a threat to masculinity. "Black manhood, then, depends on men's ability to be provider, progenitor, and protector. But, as the Black male performance of parts of this script is thwarted by economic and cultural factors, the performance of Black masculinity becomes predicated on a particular performance of Black sexuality and avoidance of weakness and femininity. If sexuality remains one of the few ways that Black men can recapture a masculinity withheld from them in the marketplace, endorsing Black homosexuality subverts the cultural project of reinscribing masculinity within the Black community." This critical view is influenced by Internalized homophobia. "Internalized homophobia is defined as the lesbian, gay, or bisexual individual's inward direction of society's homophobic attitudes (Meyer 1995)."[65]

A homophobic culture is sustained in the African-American community through the church because religion is a vital part of the African-American community: "As reported by Peterson and Jones (2009), AA MSM tended to be more involved with religious communities than NHW MSM." Because the church reiterates this stigma of homosexuality, the African-American community has higher rates of internalized homophobia. This internalized homophobia causes a lower chance of HIV/AIDS education on prevention and care within the African-American community.[65]

Sex education varies throughout the United States and in some areas could use more informative measures. African-Americans and Hispanic/Latinos experience higher rates of lower socioeconomic statuses and fewer opportunities than white people. This causes limited access to (higher) education in lower socioeconomic areas. Sex education on HIV prevention has decreased from 64% (2000) to 41% (2014). Out of the 50 states, 26 put a larger emphasis on abstinence sex education. Abstinence-only sex education is correlated to increasing rates of HIV especially in teenagers and young adults.[67]

With mass incarceration of the African-American community, HIV has been spreading rapidly throughout jails and prisons. "Among jail populations, African American men are 5 times as likely as white men, and twice as likely as Hispanic/Latino men, to be diagnosed with HIV." Since most people contract HIV before being incarcerated, it is hard to know who has the disease and to keep it from spreading. Typical prison culture often makes transmission of HIV nearly an endemic problem to deal with. Many prisoners will either force themselves upon or be forced into sexual encounters, which coupled with a lack of condoms, often results in many prisoners contracting and spreading the disease further. Many inmates do not disclose their high-risk behaviors, such as injection drug use, because they fear being stigmatized and ostracized by other inmates. There is also a lack of educational programs on disease prevention for inmates. Because "nine out of ten jail inmates are released in under 72 hours which makes it hard to test them for HIV and help them find treatment," the problem persists outside of prison.[68]

Activism and response

Starting in the early 1980s, AIDS activist groups and organizations began to emerge and advocate for people infected with HIV in the United States. Though it was an important aspect of the movement, activism went beyond the pursuit of funding for AIDS research. Groups acted to educate and raise awareness of the disease and its effects on different populations, even those thought to be at low-risk of contracting HIV. This was done through publications and "alternative media" created by those living with or close to the disease.[69]

In contrast to this "alternative media" created by activist groups, mass media reports on AIDS were not as prevalent, most likely due to the stigma surrounding the topic. The general public was therefore not exposed to information regarding the disease. In addition, the federal government and laws in place essentially prevented individuals afflicted with AIDS from getting sufficient information about the disease. Risk reduction education was not easily accessible, so activist groups took action in releasing information to the public through these publications.[70]

Activist groups worked to prevent spread of HIV by distributing information about safe sex. They also existed to support people living with HIV/AIDS, offering therapy, support groups, and hospice care.[71] Organizations like Gay Men's Health Crisis, Proyecto ContraSIDA por Vida, the Lesbian AIDS Project, and SisterLove were created to address the needs of certain populations living with HIV/AIDS. Other groups, like the NAMES Project, emerged as a way of memorializing those who had passed, refusing to let them be forgotten by the historical narrative. One group, the Association for Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment (ADAPT), headed by Yolanda Serrano, coordinated with their local prison, Riker's Island Correctional Facility, to advocate for those imprisoned and AIDS positive to be released early, so that they could pass away in the comfort of their own homes.[72]

Both men and women, heterosexual and queer populations were active in establishing and maintaining these parts of the movement. Because AIDS was initially thought only to impact gay men, most narratives of activism focus on their contributions to the movement. However, women also played a significant role in raising awareness, rallying for change, and caring for those impacted by the disease. Lesbians helped organize and spread information about transmission between women, as well as supporting gay men in their work. Narratives of activism also tend to focus on organizing done in coastal cities, but AIDS activism was present and widespread across both urban and more rural areas of the United States. Organizers sought to address needs specific to their communities, whether that was working to establish needle exchange programs, fighting against housing or employment discrimination, or issues faced primarily by people identified as members of specific groups (such as sex workers, mothers and children, or incarcerated people).

Initially when the AIDS epidemic surfaced in the United States, a large proportion of patients were LGBT community members, leading to stigmatization of the disease. Because of this, the AIDS activist groups took initiative in testing and experimenting with new possible medications for treating HIV, after researchers outside of the community refused. This research originally done by early activist groups contributed to treatments still being used today.[73]

Among the landmark legal cases in gay rights on the topic of AIDS is Braschi vs. Stahl. Litigant Miguel Braschi sued his landlord for the right to continue living in their rent controlled apartment after his gay partner Leslie Blanchard died of AIDS.[74] The NY Court of Appeals became the first American appellate court to conclude that same-sex relationships are entitled to legal recognition.[75] The case was litigated at the height of the AIDS crisis and the plaintiff himself died only a year after his groundbreaking court victory. The case focused on emotional and economic interdependency rather than on the existence of legal formalities; the verdict more difficult for government officials to reject the notion that same-sex couples could constitute families and that they were entitled to at least some of the protections afforded by law.[76]

Catholic Church

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops was the first church body to address the pandemic in 1987 with a document entitled "On "The Many Faces of AIDS: A Gospel Response."[77] In the document they said the church must provide pastoral care to those infected with HIV as well as medical care.[78][79] It called discrimination against people with AIDS "unjust and immoral.",[79] but rejected extra-marital sex and the use of condoms to halt the spread of the disease.[79] They reiterated the Church's teaching that human sexuality was a gift and was to be used in monogamous marriages.[79]

The Catholic Church, with over 117,000 health centers, is the largest private provider of HIV/AIDS care.[80] Individual dioceses around the United States began hiring staff in the 1980s to coordinate AIDS ministry.[81] By 2008, Catholic Charities USA had 1,600 agencies providing services to AIDS sufferers, including housing and mental health services.[82] The Archdiocese of New York opened a shelter for AIDS patients in 1985.[83] In the same year, they opened a hotline for people to call for resources and information.[83] The Missionaries of Charity, led by Mother Teresa, opened hospices in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York, Washington D.C., and San Francisco in the 1980s.[84][83] Individual parishes began opening hospices for AIDS patients, with the first being in New Orleans in 1985.[83][85]

The bishops of the United States issued a pastoral letter in the 1980s titled, "A Call to Compassion," saying those with AIDS "deserve to remain within our communal consciousness and to be embraced with unconditional love."[86] In Always Our Children, their 1997 pastoral letter on homosexuality, the American bishops noted "an importance and urgency" to minister to those with AIDS, especially considering the impact it had on the gay community.[87] They encouraged church ministers to include prayers at Mass for those with AIDS and those who care for them, those who have died from AIDS, and all of their friends, families, and companions.[87] They recommended special masses be said for healing with anointing of the sick or other events to take place around the time of World AIDS Day.[87] They asked every Catholic to stand in solidarity with those who were affected by the disease.[88]

In 1987, the bishops of California issued a document saying that just as Jesus loved and healed lepers, the blind, the lame, and others, so too should Catholics care for those with AIDS.[83] The year before, they publicly denounced Proposition 64, a measure pushed by Lyndon H. LaRouche to forcibly quarantine those with AIDS, and encouraged Catholics to vote against it.[84] Joseph L. Bernardin, the Archbishop of Chicago, issued a 12-page policy paper in 1986 that outlined "sweeping pastoral initiatives" his archdiocese would be undertaking.[84]

Present day activism

An effective response to HIV/AIDS requires that groups of vulnerable populations have access to HIV prevention programs with information and services that are specific to them.[89] In the present day, some activist groups and AIDS organizations that were established during the height of the epidemic are still present and working to assist people living with AIDS.[71] They may offer any combination of the following: health education, counseling and support, or advocacy for law and policy. AIDS organizations also continue to call for public awareness and support through participation in events like pride parades, World AIDS Day, or AIDS walks. Newer activism has appeared in advocacy for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), which has shown to significantly limit transmission of HIV.

Current status

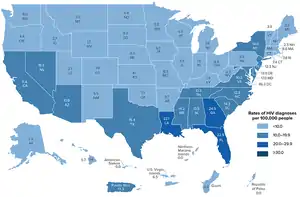

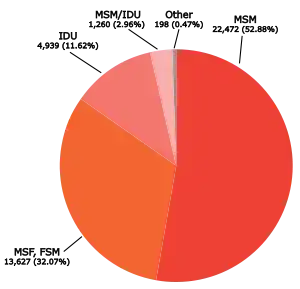

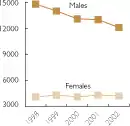

The CDC estimates at the end of 2017, there were 1,018,346 adults and adolescents with diagnosed HIV in the US and dependent areas.[1] Since 2010, the number of people living with HIV has increased, while the annual number of new HIV infections has declined to 37,832 diagnosed in 2018.[1] Within the overall estimates, however, some groups are affected more than others. 70% of 2018 diagnoses were among men who have sex with men, 7% were among injection drug users, and new infections disproportionately occurred among heterosexual women and African Americans.[1]

The most recent CDC HIV Surveillance Report estimates that 38,281 new cases of HIV were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, a rate of 11.8 per 100,000 population.[90] This rate is a decrease from the previous year's estimates, which indicated 39,589 new infections and a rate of 12.2 per 100,000 population.[90] Individuals in the age range 25–29 years-old had the highest rates of new infection, with a rate of 32.9 per 100,000.[90] With regard to race and ethnicity, the highest rates of new infections in 2017 occurred in the black/African-American population, with a new infection rate of 41.1 per 100,000. This more than doubled the next highest rate for a racial or ethnic group, which was Hispanic/Latino with a rate of 16.6 per 100,000.[90] The lowest rates of new infection in 2017 occurred in the white population and Asian population, which each had a new infection rate of 5.1 per 100,000.[90]

According to CDC estimates, the most common transmission category of new infections remained male-to-male sexual contact, which accounted for roughly 66.6% of all new infections in the United States in 2017.[90] With regard to region of residence, the highest rates of new infections in 2017 occurred in the United States South, with 19,968 total new infections and 16.1 infections per 100,000.[90] The region identified as 'South' includes Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.[90]

In the United States, men who have sex with men (MSM), described as gay and bisexual,[91] make up about 55% of the total HIV-positive population, and 83% of the estimated new HIV diagnoses among all males aged 13 and older, and approximately 92% of new HIV diagnoses among all men in their age group. 1 in 6 gay and bisexual men are therefore expected to be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime if current rates continue. Among the proportion of new HIV positive gay and bisexual men in 2017, 39% are African American, 32% are white, and 24% are Hispanic/Latino.[91] The CDC estimates that more than 600,000 gay and bisexual men are currently living with HIV in the United States.[91] A review of four studies in which trans women in the United States were tested for HIV found that 27.7% tested positive.[92]

In a 2008 study, the Center for Disease Control found that, of the study participants who were men who had sex with men ("MSM"), almost one in five (19%) had HIV and "among those who were infected, nearly half (44 percent) were unaware of their HIV status." The research found that white MSM "represent a greater number of new HIV infections than any other population, followed closely by black MSM—who are one of the most disproportionately affected subgroups in the U.S." and that most new infections among white MSM occurred among those aged 30–39 followed closely by those aged 40–49, while most new infections among black MSM have occurred among young black MSM (aged 13–29).[93][94]

In 2015, a major HIV outbreak, Indiana's largest-ever, occurred in two largely rural, economically depressed and poor counties in the southern portion of the state, due to the injection of a relatively new opioid-type drug called Opana (oxymorphone), which is designed be taken in pill form but is ground up and injected intravenously using needles. Because of the lack of HIV cases in that area beforehand and the youth of many but not all of those affected, the relative unavailability in the local area of treatment centers capable of dealing with long-term health needs, HIV care, and drug addiction during the initial phases of the outbreak, and political opposition to needle exchange programs, the outbreak expanded for months, resulting in up to 127 preventable cases. Under pressure, officials eventually declared a state of emergency, but much of the damage had already been done.[95]

See also

- Criminal transmission of HIV in the United States

- Adult Industry Medical Health Care Foundation

- AIDS Education and Training Centers (AETCs)

- People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement

- HIV/AIDS in New York City

- Hank M. Tavera

- President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (international)

- HIV/AIDS activism

- HIV/AIDS activists

International:

References

- "HIV/AIDS Basic Statistics". Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 18, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- McDow, Thomas F. (October 2018). "A Century of HIV". Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- "A Timeline of HIV and AIDS". HIV.gov. May 11, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- "United States Code: Immigration and Nationality" (PDF). Library of Congress. Office of the Law Revision Counsel. 1988. p. 1246. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Nieburg, Phillip; Morrison, J. Stephen (March 1, 2007). Moving Beyond the U.S. Government Policy of Inadmissibility of HIV-Infected Noncitizens (PDF) (PDF) (Report). pp. 7–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- "The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Basics". KFF.org. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- NCHHSTP, CDC (February 14, 2017). "New HIV Infections Drop 18 Percent in Six Years". HIV.gov.

- HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2013 (PDF). New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Padamsee, Tasleem J (August 1, 2020). "Fighting an Epidemic in Political Context: Thirty-Five Years of HIV/AIDS Policy Making in the United States". Social History of Medicine. 33 (3): 1001–1028. doi:10.1093/shm/hky108. ISSN 0951-631X. PMC 7784248. PMID 33424441.

- Gambardella, Alfonso; Gambardella, Professor of Economics and Management Laboratory of Economics and Management Alfonso (March 9, 1995). Science and Innovation: The US Pharmaceutical Industry During the 1980s. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45118-5.

- Henry, Martha (July 21, 2016). "Florence Revisited: America's History of HIV Travel Restrictions".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Lazzarini, Zita; Galletly, Carol L.; Mykhalovskiy, Eric; Harsono, Dini; O’Keefe, Elaine; Singer, Merrill; Levine, Robert J. (June 13, 2013). "Criminalization of HIV Transmission and Exposure: Research and Policy Agenda". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (8): 1350–1353. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301267. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3966663. PMID 23763428.

- Wilson, Phill; Wright, Kai; Isbell, Michael T. (August 2008). "Left Behind: Black America: a Neglected Priority in the Global AIDS Epidemic" (PDF). Black AIDS Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- "Deaths in New York City Reached Historic Low in 2002" (Press release). New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. January 30, 2004. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- "Federal Register Volume 52, Issue 167 (August 28, 1987)". govinfo.gov. Office of the Federal Register. pp. 32540–32544. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act No. Sec. 2007 of 1993. 103rd Congress.

- Morin, Stephen F; Carrillo, Héctor; Steward, Wayne T; Maiorana, Andre; Trautwein, Mark; Gómez, Cynthia A (November 2004). "Policy Perspectives on Public Health For Mexican Migrants in California". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 37: S252–S259. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000141254.61840.05. PMID 15722867. S2CID 1962566.

- Mahto, M; Ponnusamy, K; Schuhwerk, M; Richens, J; Lambert, N; Wilkins, E; Churchill, DR; Miller, RF; Behrens, RH (May 2006). "Knowledge, attitudes and health outcomes in HIV-infected travellers to the USA". HIV Medicine. 7 (4): 201–204. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00371.x. PMID 16630031. S2CID 23404829.

- R. Yates, William (November 2, 2004). Exception to Nonimmigrant HIV Waiver Policy for K and V Nonimmigrants (PDF) (PDF) (Report). U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Russell, Sabin (December 2, 2006). "Bush to ease rule limiting HIV-positive foreign visitors". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- "Activist helps US HIV law change". BBC News. July 6, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- Crowley, Jeffrey (October 30, 2009). "Honoring the Legacy of Ryan White". whitehouse.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2010 – via National Archives.

- "Final Rule Removing HIV Infection from U.S. Immigration Screening". United States Department of State. January 19, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- Yehia, Baligh; Frank, Ian (2011). "Battling AIDS in America: An Evaluation of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (9): e4–e8. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300259. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3154226. PMID 21778507.

- Collins, Chris. (2007). Improving outcomes blueprint for a national AIDS plan for the United States. Open Society Institute. OCLC 1100047917.

- United States. Office of National AIDS Policy. (2010). National HIV/AIDS strategy : federal implementation plan. White House Office of National AIDS Policy. OCLC 656320879.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "Halting U.S. HIV Epidemic By 2030: Difficult But Doable". NPR.org.

- "Some Big Health Care Policy Changes Are Hiding In The Federal Spending Package". NPR.org.

- Lavoie, Denise (April 11, 2022). "Judge Rules U.S. Military Can't Discharge HIV-Positive Troops". HuffPost. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- "HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: U.S. HIV and AIDS cases reported through December 2001" (PDF). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Vol. 13, no. 2. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- "HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2012–2013" (PDF). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Vol. 24. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 23, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- Westengard, Laura (2019). "Monstrosity: Melancholia, Cannibalism, and HIV/AIDS". Gothic Queer Culture: Marginalized Communities and the Ghosts of Insidious Trauma. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 99–103. ISBN 978-1-4962-0204-8. LCCN 2018057900.

- Kahn Best, Rachel (2012). "Disease Politics and Medical Research Funding: Three Ways Advocacy Shapes Policy". American Sociological Review. 77 (5): 780–803. doi:10.1177/0003122412458509.

- "Bloodborne Infectious Diseases HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus". US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. March 10, 2010. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- Small, Neil. "Dying in a Public Place: AIDS Deaths." The Sociological Review 40, no. 1_suppl (May 1992): 87–111.

- Bayer, Ronald (2000). Aids Doctors Voices from the Epidemic. Oxford University. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-19-512681-5.

- Link, Nathan (April 1988). "Concerns of Medical and Pediatric House Officers about Acquiring AIDS from their Patients". American Journal of Public Health: 445–459.

- Gerbert, Barbara (1991). "Primary Care Physicians and AIDS". Journal of the American Medical Association. 266 (20): 2837–2842. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03470200049033.

- "HIV and African Americans | Race/Ethnicity | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. March 19, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- Steiner, Riley J.; Finocchario-Kessler, Sarah; Dariotis, Jacinda K. (2013). "Engaging HIV Care Providers in Conversations With Their Reproductive-Age Patients About Fertility Desires and Intentions: A Historical Review of the HIV Epidemic in the United States". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (8): 1357–1366. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301265. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 4007857. PMID 23763424.

- "Report: Black U.S. AIDS rates rival some African nations - CNN.com". www.cnn.com. July 29, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- CDC (July 1, 2022). "HIV in the United States by Race/Ethnicity: Viral Suppression". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- Peragallo (2005). "A Randomized Clinical Trial of an HIV-Risk-Reduction Intervention Among Low-Income Latino Women". Nursing Research. 54 (4): 264. doi:10.1097/00006199-200507000-00008. ISSN 0029-6562.

- "HIV and Hispanics/Latinos". CDC.gov. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. August 21, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "HIV and American Indians and Alaska Natives". CDC.gov. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- "A Briefing on HIV/AIDS in Indian Country - Fall 2017" (PDF). nihb.org. National Indian Health Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- "HIV among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States". cdc.org. August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- "HIV in American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States". cdc.org. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- "Issue Brief: Native Gay Men and Two Spirit People" (PDF). nastad.org. National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- CDC (April 14, 2022). "HIV in the United States by Race/Ethnicity: PrEP Coverage". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- "Impact on Racial and Ethnic Minorities". HIV.gov. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- Green, Jonathon (2006). Cassell's Dictionary of Slang. Sterling Publishing. p. 893. ISBN 978-0-304-36636-1. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

down low n. [1990s+] (US Black) a state of secrecy. down low adj. [1990s+] () covert, secret (i.e. keeping a low profile)

- Bond, Lisa; Wheeler, Darrell P.; Millett, Gregorio A.; LaPollo, Archana B.; Carson, Lee F.; Liau, Adrian (April 2009). Morabia, Alfredo (ed.). "Black Men Who Have Sex With Men and the Association of Down-Low Identity With HIV Risk Behavior". American Journal of Public Health. American Public Health Association. 99 (Suppl 1): S92–S95. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.127217. eISSN 1541-0048. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 2724949. PMID 19218177. S2CID 40119540.

- Hovey, Jaime (2007). "Sexual subcultures". In Malti-Douglas, Fedwa (ed.). Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender. Macmillan Social Science Library. Vol. 4. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 1372–1374. ISBN 9780028661155. OCLC 922889305.

- King, J.L.; Carreras, Courtney (April 25, 2006). "Coming Up from the Down Low: The Journey to Acceptance, Healing and Honest Love". Three Rivers Press. p. 36. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Johnson, Jason (May 1, 2005). "Secret gay encounters of black men could be raising women's infection rate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Mutua, Athena (September 28, 2006). Progressive Black Masculinities. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-415-97687-9. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Bennett, Jessica (May 19, 2008). "Outing Hip-Hop". Newsweek. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- Heath, Jessie; Goggin, Kathy (January 2009). "Attitudes Towards Male Homosexuality, Bisexuality, and the Down Low Lifestyle: Demographic Differences and HIV Implications". Journal of Bisexuality. 9 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1080/15299710802659997. S2CID 143995029.

- Denizet-Lewis, Benoit (August 3, 2003). "Double Lives On The Down Low". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- Wright, Kaimeans (June 5, 2001). "The Great Down-Low Debate: A New Black Sexual Identity May Be an Incubator for AIDS". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- "Sex, lies and the "down low"". Salon.com. August 16, 2004. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- "CDC: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report". CDC: US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. February 7, 2003. Archived from the original on October 5, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

- Armstrong, Katrina; Putt, Mary; Halbert, Chanita H.; Grande, David; Schwartz, Jerome Sanford; Liao, Kaijun; Marcus, Noora; Demeter, Mirar B.; Shea, Judy A. (February 2013). "Prior Experiences of Racial Discrimination and Racial Differences in Health Care System Distrust". Medical Care. 51 (2): 144–150. doi:10.1097/mlr.0b013e31827310a1. ISSN 0025-7079. PMC 3552105. PMID 23222499.

- Hill, William Allen; McNeely, Clea (2013). "HIV/AIDS Disparity between African-American and Caucasian Men Who Have Sex with Men: Intervention Strategies for the Black Church". Journal of Religion and Health. 52 (2): 475–487. doi:10.1007/s10943-011-9496-2. JSTOR 24484999. PMID 21538178. S2CID 9557761.

- Robertson, Gil (2006). Not In My Family. Canada: Agate. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-1-932841-24-4.

- "HIV and AIDS in the United States of America (USA)". AVERT. July 21, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "HIV Among Incarcerated Populations in the United States".

- Juhasz, Alexandra (1995). AIDS TV: Identity, Community, and Alternative Video. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1695-4.

- HEREK, GREGORY M. (1999). "AIDS and Stigma". American Behavioral Scientist. 42 (7): 1106–1116. doi:10.1177/0002764299042007004. ISSN 0002-7642. S2CID 143610161.

- Ross, Loretta (2017). Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28820-1.

- Carter, Zoe (May 9, 1988). ADAPT and Survive. New York Magazine.

- Corburn, Jason. (2005). Street science : community knowledge and environmental health justice. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03333-X. OCLC 58830060.

- Gutis, Philip S.; Times, Special To the New York (July 7, 1989). "New York Court Defines Family To Include Homosexual Couples". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "From the Closet to the Courtroom | Rutgers Magazine". ucmweb.rutgers.edu. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Courts, Author Historical Society of the New York (September 12, 2019). "The Braschi Breakthrough: 30 Years Later, Looking Back on the Relationship Recognition Landmark". Historical Society of the New York Courts. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Gravend-Tirole, Xavier (November 30, 2008). "Catholicism and the AIDS Pandemic". In Sharma, Arvind (ed.). The World's Religions after September 11. ABC-CLIO. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-275-99622-2. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Kasza 2007, p. 170.

- Smith, Raymond A. (August 27, 1998). Encyclopedia of AIDS: A Social, Political, Cultural, and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-135-45754-9. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Catholic AIDS workers: Pope echoing us on condoms". The Mercury News. Associated Press. December 1, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education 1993, p. 139-140.

- "AIDS and the Catholic Church - Pavement Pieces". Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education 1993, p. 139.

- Hyer, Marorie (October 31, 1986). "Bishop Urges Church Action On AIDS Care". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Finney Jr., Peter (May 4, 2019). "New Orleans priest founded first Catholic AIDS hospice". Crux. Catholic News Service. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Reinhld, RObert (September 17, 1987). "AIDS Issue at Fore as Pope Visits San Francisco Today". The New York Times. p. 33. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Kasza 2007, p. 171.

- Kasza 2007, p. 172.

- "Key Affected Populations, HIV and AIDS". Avert: Global Information and Education on HIV and AIDS. July 24, 2015.

- "HIV Surveillance | Reports| Resource Library | HIV/AIDS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "Gay and Bisexual Men – HIV by Group". www.cdc.gov. February 27, 2018.

- Herbst, J. H; Jacobs, E. D; Finlayson, T. J; McKleroy, V. S; Neumann, M. S; Crepaz, N; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team (January 2008). "Estimating HIV Prevalence and Risk Behaviors of Transgender Persons in the United States: A Systematic Review" (PDF). AIDS Behav. 12 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3. PMID 17694429. S2CID 22946778. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- "CDC Fact Sheet – HIV and AIDS among Gay and Bisexual Men – Sept 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- "CDC: One In Five Gay Men HIV-Positive". Kaiser Health News. September 24, 2010.

- Gonsalves, Greg; Crawford, Forrest (March 2, 2020). "How Mike Pence Made Indiana's HIV Outbreak Worse". Politico. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

Bibliography

- Cante, Richard C. (March 2008). Gay Men and the Forms of Contemporary US Culture. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-7230-2.

- Bogart, Laura; Thorburn, Sheryl (February 2005). "Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans?". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 38 (2): 213–8. doi:10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014. PMID 15671808. S2CID 9659696.

- Walker, Robert Searles (1994). AIDS: Today, Tomorrow : an Introduction to the HIV Epidemic in America (2nd ed.). Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press Intl. ISBN 978-0-391-03859-2. OCLC 30399464.

- Siplon, Patricia (2002). AIDS and the policy struggle in the United States. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-378-3. OCLC 48964730.

- National Research Council; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Panel on Monitoring the Social Impact of the AIDS Epidemic (February 1, 1993). The Social Impact of AIDS in the United States. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-04628-2. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

Further reading

- Buso, Michael Alan (2017). "Here There Is No Plague": The Ideology and Phenomenology of AIDS in Gay Literature AIDS in Gay Literature. University of West Virginia. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020. - Document ID 5291