Health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health professionals and allied health fields. Medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, midwifery, nursing, optometry, audiology, psychology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, athletic training, and other health professions all constitute health care. It includes work done in providing primary care, secondary care, and tertiary care, as well as in public health.

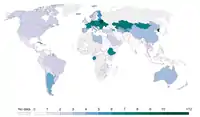

Access to health care may vary across countries, communities, and individuals, influenced by social and economic conditions as well as health policies. Providing health care services means "the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes".[3] Factors to consider in terms of health care access include financial limitations (such as insurance coverage), geographical and logistical barriers (such as additional transportation costs and the possibility to take paid time off work to use such services), sociocultural expectations, and personal limitations (lack of ability to communicate with health care providers, poor health literacy, low income).[4] Limitations to health care services affects negatively the use of medical services, the efficacy of treatments, and overall outcome (well-being, mortality rates).

Health systems are organizations established to meet the health needs of targeted populations. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a well-functioning health care system requires a financing mechanism, a well-trained and adequately paid workforce, reliable information on which to base decisions and policies, and well-maintained health facilities to deliver quality medicines and technologies.

An efficient health care system can contribute to a significant part of a country's economy, development, and industrialization. Health care is conventionally regarded as an important determinant in promoting the general physical and mental health and well-being of people around the world.[5] An example of this was the worldwide eradication of smallpox in 1980, declared by the WHO as the first disease in human history to be eliminated by deliberate health care interventions.[6]

Delivery

The delivery of modern health care depends on groups of trained professionals and paraprofessionals coming together as interdisciplinary teams.[7] This includes professionals in medicine, psychology, physiotherapy, nursing, dentistry, midwifery and allied health, along with many others such as public health practitioners, community health workers and assistive personnel, who systematically provide personal and population-based preventive, curative and rehabilitative care services.

While the definitions of the various types of health care vary depending on the different cultural, political, organizational, and disciplinary perspectives, there appears to be some consensus that primary care constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process and may also include the provision of secondary and tertiary levels of care.[8] Health care can be defined as either public or private.

Primary care

Primary care refers to the work of health professionals who act as a first point of consultation for all patients within the health care system.[8][10] Such a professional would usually be a primary care physician, such as a general practitioner or family physician. Another professional would be a licensed independent practitioner such as a physiotherapist, or a non-physician primary care provider such as a physician assistant or nurse practitioner. Depending on the locality, health system organization the patient may see another health care professional first, such as a pharmacist or nurse. Depending on the nature of the health condition, patients may be referred for secondary or tertiary care.

Primary care is often used as the term for the health care services that play a role in the local community. It can be provided in different settings, such as Urgent care centers that provide same-day appointments or services on a walk-in basis.

Primary care involves the widest scope of health care, including all ages of patients, patients of all socioeconomic and geographic origins, patients seeking to maintain optimal health, and patients with all types of acute and chronic physical, mental and social health issues, including multiple chronic diseases. Consequently, a primary care practitioner must possess a wide breadth of knowledge in many areas. Continuity is a key characteristic of primary care, as patients usually prefer to consult the same practitioner for routine check-ups and preventive care, health education, and every time they require an initial consultation about a new health problem. The International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) is a standardized tool for understanding and analyzing information on interventions in primary care based on the reason for the patient's visit.[11]

Common chronic illnesses usually treated in primary care may include, for example, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, COPD, depression and anxiety, back pain, arthritis or thyroid dysfunction. Primary care also includes many basic maternal and child health care services, such as family planning services and vaccinations. In the United States, the 2013 National Health Interview Survey found that skin disorders (42.7%), osteoarthritis and joint disorders (33.6%), back problems (23.9%), disorders of lipid metabolism (22.4%), and upper respiratory tract disease (22.1%, excluding asthma) were the most common reasons for accessing a physician.[12]

In the United States, primary care physicians have begun to deliver primary care outside of the managed care (insurance-billing) system through direct primary care which is a subset of the more familiar concierge medicine. Physicians in this model bill patients directly for services, either on a pre-paid monthly, quarterly, or annual basis, or bill for each service in the office. Examples of direct primary care practices include Foundation Health in Colorado and Qliance in Washington.

In the context of global population aging, with increasing numbers of older adults at greater risk of chronic non-communicable diseases, rapidly increasing demand for primary care services is expected in both developed and developing countries.[13][14] The World Health Organization attributes the provision of essential primary care as an integral component of an inclusive primary health care strategy.[8]

Secondary care

Secondary care includes acute care: necessary treatment for a short period of time for a brief but serious illness, injury, or other health condition. This care is often found in a hospital emergency department. Secondary care also includes skilled attendance during childbirth, intensive care, and medical imaging services.[16]

The term "secondary care" is sometimes used synonymously with "hospital care". However, many secondary care providers, such as psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, most dental specialties or physiotherapists, do not necessarily work in hospitals. Some primary care services are delivered within hospitals. Depending on the organization and policies of the national health system, patients may be required to see a primary care provider for a referral before they can access secondary care.[17][18]

In countries that operate under a mixed market health care system, some physicians limit their practice to secondary care by requiring patients to see a primary care provider first. This restriction may be imposed under the terms of the payment agreements in private or group health insurance plans. In other cases, medical specialists may see patients without a referral, and patients may decide whether self-referral is preferred.

In other countries patient self-referral to a medical specialist for secondary care is rare as prior referral from another physician (either a primary care physician or another specialist) is considered necessary, regardless of whether the funding is from private insurance schemes or national health insurance.

Allied health professionals, such as physical therapists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and dietitians, also generally work in secondary care, accessed through either patient self-referral or through physician referral.

Tertiary care

Tertiary care is specialized consultative health care, usually for inpatients and on referral from a primary or secondary health professional, in a facility that has personnel and facilities for advanced medical investigation and treatment, such as a tertiary referral hospital.[19]

Examples of tertiary care services are cancer management, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, plastic surgery, treatment for severe burns, advanced neonatology services, palliative, and other complex medical and surgical interventions.[20]

Quaternary care

The term quaternary care is sometimes used as an extension of tertiary care in reference to advanced levels of medicine which are highly specialized and not widely accessed. Experimental medicine and some types of uncommon diagnostic or surgical procedures are considered quaternary care. These services are usually only offered in a limited number of regional or national health care centers.[20][21]

Home and community care

Many types of health care interventions are delivered outside of health facilities. They include many interventions of public health interest, such as food safety surveillance, distribution of condoms and needle-exchange programs for the prevention of transmissible diseases.

They also include the services of professionals in residential and community settings in support of self-care, home care, long-term care, assisted living, treatment for substance use disorders among other types of health and social care services.

Community rehabilitation services can assist with mobility and independence after the loss of limbs or loss of function. This can include prostheses, orthotics, or wheelchairs.

Many countries, especially in the west, are dealing with aging populations, so one of the priorities of the health care system is to help seniors live full, independent lives in the comfort of their own homes. There is an entire section of health care geared to providing seniors with help in day-to-day activities at home such as transportation to and from doctor's appointments along with many other activities that are essential for their health and well-being. Although they provide home care for older adults in cooperation, family members and care workers may harbor diverging attitudes and values towards their joint efforts. This state of affairs presents a challenge for the design of ICT (information and communication technology) for home care.[22]

Because statistics show that over 80 million Americans have taken time off of their primary employment to care for a loved one,[23] many countries have begun offering programs such as the Consumer Directed Personal Assistant Program to allow family members to take care of their loved ones without giving up their entire income.

With obesity in children rapidly becoming a major concern, health services often set up programs in schools aimed at educating children about nutritional eating habits, making physical education a requirement and teaching young adolescents to have a positive self-image.

Ratings

Health care ratings are ratings or evaluations of health care used to evaluate the process of care and health care structures and/or outcomes of health care services. This information is translated into report cards that are generated by quality organizations, nonprofit, consumer groups and media. This evaluation of quality is based on measures of:

- hospital quality

- health plan quality

- physician quality

- quality for other health professionals

- of patient experience

Related sectors

Health care extends beyond the delivery of services to patients, encompassing many related sectors, and is set within a bigger picture of financing and governance structures.

Health system

A health system, also sometimes referred to as health care system or healthcare system, is the organization of people, institutions, and resources that deliver health care services to populations in need.

Healthcare industry

The healthcare industry incorporates several sectors that are dedicated to providing health care services and products. As a basic framework for defining the sector, the United Nations' International Standard Industrial Classification categorizes health care as generally consisting of hospital activities, medical and dental practice activities, and "other human health activities." The last class involves activities of, or under the supervision of, nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, scientific or diagnostic laboratories, pathology clinics, residential health facilities, patient advocates[24] or other allied health professions.

In addition, according to industry and market classifications, such as the Global Industry Classification Standard and the Industry Classification Benchmark, health care includes many categories of medical equipment, instruments and services including biotechnology, diagnostic laboratories and substances, drug manufacturing and delivery.

For example, pharmaceuticals and other medical devices are the leading high technology exports of Europe and the United States.[25][26] The United States dominates the biopharmaceutical field, accounting for three-quarters of the world's biotechnology revenues.[25][27]

Health care research

The quantity and quality of many health care interventions are improved through the results of science, such as advanced through the medical model of health which focuses on the eradication of illness through diagnosis and effective treatment. Many important advances have been made through health research, biomedical research and pharmaceutical research, which form the basis for evidence-based medicine and evidence-based practice in health care delivery. Health care research frequently engages directly with patients, and as such issues for whom to engage and how to engage with them become important to consider when seeking to actively include them in studies. While single best practice does not exist, the results of a systematic review on patient engagement suggest that research methods for patient selection need to account for both patient availability and willingness to engage.[28]

Health services research can lead to greater efficiency and equitable delivery of health care interventions, as advanced through the social model of health and disability, which emphasizes the societal changes that can be made to make populations healthier.[29] Results from health services research often form the basis of evidence-based policy in health care systems. Health services research is also aided by initiatives in the field of artificial intelligence for the development of systems of health assessment that are clinically useful, timely, sensitive to change, culturally sensitive, low-burden, low-cost, built into standard procedures, and involve the patient.[30]

Health care financing

There are generally five primary methods of funding health care systems:[32]

- General taxation to the state, county or municipality

- Social health insurance

- Voluntary or private health insurance

- Out-of-pocket payments

- Donations to health charities

In most countries, there is a mix of all five models, but this varies across countries and over time within countries. Aside from financing mechanisms, an important question should always be how much to spend on health care. For the purposes of comparison, this is often expressed as the percentage of GDP spent on health care. In OECD countries for every extra $1000 spent on health care, life expectancy falls by 0.4 years.[33] A similar correlation is seen from the analysis carried out each year by Bloomberg.[34] Clearly this kind of analysis is flawed in that life expectancy is only one measure of a health system's performance, but equally, the notion that more funding is better is not supported.

In 2011, the health care industry consumed an average of 9.3 percent of the GDP or US$ 3,322 (PPP-adjusted) per capita across the 34 members of OECD countries. The US (17.7%, or US$ PPP 8,508), the Netherlands (11.9%, 5,099), France (11.6%, 4,118), Germany (11.3%, 4,495), Canada (11.2%, 5669), and Switzerland (11%, 5,634) were the top spenders, however life expectancy in total population at birth was highest in Switzerland (82.8 years), Japan and Italy (82.7), Spain and Iceland (82.4), France (82.2) and Australia (82.0), while OECD's average exceeds 80 years for the first time ever in 2011: 80.1 years, a gain of 10 years since 1970. The US (78.7 years) ranges only on place 26 among the 34 OECD member countries, but has the highest costs by far. All OECD countries have achieved universal (or almost universal) health coverage, except the US and Mexico.[35][36] (see also international comparisons.)

In the United States, where around 18% of GDP is spent on health care,[34] the Commonwealth Fund analysis of spend and quality shows a clear correlation between worse quality and higher spending.[37]

Administration and regulation

The management and administration of health care is vital to the delivery of health care services. In particular, the practice of health professionals and the operation of health care institutions is typically regulated by national or state/provincial authorities through appropriate regulatory bodies for purposes of quality assurance.[38] Most countries have credentialing staff in regulatory boards or health departments who document the certification or licensing of health workers and their work history.[39]

Health information technology

Health information technology (HIT) is "the application of information processing involving both computer hardware and software that deals with the storage, retrieval, sharing, and use of health care information, data, and knowledge for communication and decision making."[40]

Health information technology components:

- Electronic Health Record (EHR) - An EHR contains a patient's comprehensive medical history, and may include records from multiple providers.[41]

- Electronic Medical Record (EMR) - An EMR contains the standard medical and clinical data gathered in one's provider's office.[41]

- Personal Health Record (PHR) - A PHR is a patient's medical history that is maintained privately, for personal use.[42]

- Medical Practice Management software (MPM) - is designed to streamline the day-to-day tasks of operating a medical facility. Also known as practice management software or practice management system (PMS).

- Health Information Exchange (HIE) - Health Information Exchange allows health care professionals and patients to appropriately access and securely share a patient's vital medical information electronically.[43]

See also

- Category:Health care by country

- Healthcare system / Health professionals

- Health equity

- Health policy

- Tobacco control laws

- Universal health care

By country:

References

- "Hospital beds per 1,000 people". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams Announce Plan for SPARC Kips Bay, First-of-Its-Kind Job and Education Hub for Health and Life Sciences Innovation". State of New York. October 13, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services; Millman, M. (1993). Access to Health Care in America. The National Academies Press, US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. doi:10.17226/2009. ISBN 978-0-309-04742-5. PMID 25144064.

- "Healthcare Access in Rural Communities Introduction". Rural Health Information Hub. 2019. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- "Health Topics: Health Systems". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- World Health Organization. Anniversary of smallpox eradication. Geneva, 18 June 2010.

- United States Department of Labor. Employment and Training Administration: Health care Archived 2012-01-29 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- Thomas-MacLean R et al. No Cookie-Cutter Response: Conceptualizing Primary Health Care. Archived 2019-04-12 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "June 2014". Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- World Health Organization. Definition of Terms. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2). Archived 2020-12-22 at the Wayback Machine Geneva. Accessed 24 June 2011.

- St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. (January 2013). "Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population". Mayo Clin. Proc. 88 (1): 56–67. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.020. PMC 3564521. PMID 23274019.

- World Health Organization. Aging and life course: Our aging world. Archived 2019-06-11 at the Wayback Machine Geneva. Accessed 24 June 2011.

- Simmons J. Primary Care Needs New Innovations to Meet Growing Demands. Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine HealthLeaders Media, May 27, 2009.

- "100 of the largest hospitals and health systems in America," Becker's Hospital Review

- "Health Care System". the Free Medical Dictionary. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- "Secondary Care". MS Trust. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "Difference between primary, secondary and tertiary health care". EInsure. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Patient Care: Tertiary Care Definition. Archived 2017-07-11 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 27 June 2011.

- Emory University. School of Medicine. Archived 2011-04-23 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 27 June 2011.

- Alberta Physician Link. Levels of Care. Archived 2014-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- Christensen, L.R.; Grönvall, E. (2011). "ECSCW 2011: Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 24-28 September 2011, Aarhus Denmark". In S. Bødker; N. O. Bouvin; W. Letters; V. Wulf; L. Ciolfi (eds.). ECSCW 2011: Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 24–28 September 2011, Aarhus Denmark. London: Springer. pp. 61–80. doi:10.1007/978-0-85729-913-0_4. ISBN 978-0-85729-912-3.

- Porter, Eduardo (2017-08-29). "Home Health Care: Shouldn't It Be Work Worth Doing?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- Dorothy Kamaker (2015-09-21). "Patient advocacy services ensure optimum health outcomes". Archived from the original on 2017-12-20. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- "The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures" (pdf). European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. 2007. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- 2008 Annual Report. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. 2008.

- "Europe's competitiveness". European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- Domecq, Juan Pablo; Prutsky, Gabriela; Elraiyah, Tarig; Wang, Zhen; Nabhan, Mohammed; Shippee, Nathan; Brito, Juan Pablo; Boehmer, Kasey; Hasan, Rim; Firwana, Belal; Erwin, Patricia (2014-02-26). "Patient engagement in research: a systematic review". BMC Health Services Research. 14 (1): 89. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-89. ISSN 1472-6963. PMC 3938901. PMID 24568690.

- Bond J.; Bond S. (1994). Sociology and Health Care. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-04059-7.

- Erik Cambria; Tim Benson; Chris Eckl; Amir Hussain (2012). "Sentic PROMs: Application of Sentic Computing to the Development of a Novel Unified Framework for Measuring Health-Care Quality". Expert Systems with Applications, Elsevier. Vol. 39. pp. 10533–10543. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.120.

- Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (22 August 2016). "Global Health". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- World Health Organization. "Regional Overview of Social Health Insurance in South-East Asia.' Archived 2012-09-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 02, 2014.

- "Improve operational efficiency in healthcare with RPA". NuAIg. 2021-03-02. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- "These Are the Economies With the Most (and Least) Efficient Health Care". BloombergQuint. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- "Health at a Glance 2013 - OECD Indicators" (PDF). OECD. 2013-11-21. pp. 5, 39, 46, 48. (link). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Health Status, Life expectancy, Total population at birth, 2011" (online statistics). stats.oecd.org/. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- Commonwealth Fund (2018). "Health Care Quality-Spending Interactive | Commonwealth Fund". www.commonwealthfund.org. doi:10.26099/bf4n-8j57. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- World Health Organization, 2003. Quality and accreditation in health care services. Geneva http://www.who.int/hrh/documents/en/quality_accreditation.pdf Archived 2020-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Tulenko et al., "Framework and measurement issues for monitoring entry into the health workforce." Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2012.

- "Health information technology — HIT". HealthIT.gov. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- "Definition and Benefits of Electronic Medical Records (EMR) | Providers & Professionals | HealthIT.gov". www.healthit.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- "What is a personal health record? | FAQs | Providers & Professionals | HealthIT.gov". www.healthit.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- "Official Information about Health Information Exchange (HIE) | Providers & Professionals | HealthIT.gov". www.healthit.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

External links

| Library resources about Health care |

Media related to Health care at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Health care at Wikimedia Commons Travel health travel guide from Wikivoyage

Travel health travel guide from Wikivoyage