Healthcare in Pakistan

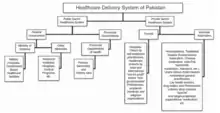

The healthcare delivery system of Pakistan (تحفّظ صحتِ عامّہ ، پاکستان) is complex because it includes healthcare subsystems by federal governments and provincial governments competing with formal and informal private sector healthcare systems.[3][2] Healthcare is delivered mainly through vertically managed disease-specific mechanisms. The different institutions that are responsible for this include: provincial and district health departments, parastatal organizations, social security institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and private sector.[4] The country's health sector is also marked by urban-rural disparities in healthcare delivery and an imbalance in the health workforce, with insufficient health managers, nurses, paramedics and skilled birth attendants in the peripheral areas.[5][6] Pakistan's gross national income per capita in 2021 was $4,990 and the total expenditure on health per capita in 2021 was Rs 657.2 Billions , constituting 1.4% of the country's GDP.[7] The health care delivery system in Pakistan consists of public and private sectors. Under the constitution, health is primarily responsibility of the provincial government, except in the federally administrated areas. Health care delivery has traditionally been jointly administered by the federal and provincial governments with districts mainly responsible for implementation. Service delivery is being organized through preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative services. The curative and rehabilitative services are being provided mainly at the secondary and tertiary care facilities. Preventive and promotive services, on the other hand, are mainly provided through various national programs; and community health workers’ interfacing with the communities through primary healthcare facilities and outreach activities. The state provides healthcare through a three-tiered healthcare delivery system and a range of public health interventions. Some government/ semi government organizations like the armed forces, Sui Gas, WAPDA, Railways, Fauji Foundation, Employees Social Security Institution and NUST provide health service to their employees and their dependents through their own system, however, these collectively cover about 10% of the population. The private health sector constitutes a diverse group of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, traditional healers, drug vendors, as well as laboratory technicians, shopkeepers and unqualified practitioners.

Despite the increase in public health facilities, Pakistan's population growth has generated an unmet need for healthcare.[8] Public healthcare institutions that address critical health issues are often only located in major towns and cities. Due to the absence of these institutions and the cost associated with transportation, impoverished people living in rural and remote areas tend to consult private doctors.[5] Studies have shown that Pakistan's private sector healthcare system is outperforming the public sector healthcare system in terms of service quality and patient satisfaction, with 70% of the population being served by the private health sector.[4][9] The private health sector operates through a fee-for-service system of unregulated hospitals, medical practitioners, homeopathic doctors, hakeems, and other spiritual healers.[8] In urban areas, some public-private partnerships exist for franchising private sector outlets and contributing to overall service delivery.[10] Very few mechanisms exist to regulate the quality, standards, protocols, ethics, or prices within the private health sector, that results in disparities in health services.[8]

Even though nurses play a key role in any country's health care field, Pakistan has only 121,245 nurses to service a population of 229 million people, leaving a shortfall of nurses as per world health organisation estimates.[11] As per the Economic Survey of Pakistan (2020-21), the country is spending 1.2% of the GDP on healthcare [12] which is less than the healthcare expenditure recommended by WHO i.e. 5% of GDP.[13]

Cancer care

Cancer information on Pakistan [14] Approximately one in every 9 Pakistani women is likely to suffer from breast cancer which is one of the highest incidence rates in Asia.[15]

Major cancer centers in Pakistan include the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center in Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar, Aga Khan University Hospital in Karachi and the National Institute of Blood Diseases (NIBD) in Karachi.

Obesity

Obesity in Pakistan is a health issue that has effected Moaz concern only in the past few years. Urbanisation and an unhealthy, energy-dense diet (the high presence of oil and fats in Pakistani cooking), as well as changing lifestyles, are among the root causes contributing to obesity in the country. According to a list of the world's "fattest countries" published on Forbes, Pakistan is ranked 165 (out of 194 countries) in terms of its overweight population, with 22.2% of individuals over the age of 15 crossing the threshold of obesity. This ratio roughly corresponds with other studies, which state one-in-four Pakistani adults as being overweight. According to the research paper published on PubMed, in Pakistan, 25% of people are either obese or overweight.[16] Moreover, according to the 2016 stats by World Health Organization (WHO), 3.3% of males and 6.4% of females in Pakistan are suffering from obesity.[17]

Research indicates that people living in large cities in Pakistan are more exposed to the risks of obesity as compared to those in the rural countryside. Women also naturally have higher rates of obesity as compared to men. Pakistan also has the highest percentage of people with diabetes in South Asia.

According to one study, fat is more dangerous for South Asians than for Caucasians because the fat tends to cling to organs like the liver instead of the skin.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition is one of the most significant public health problems in Pakistan, and especially among children. According to UNICEF, about half of children are chronically malnourished.[18] National surveys show that for almost three decades, the rates of stunting and acute undernutrition in children under five years of age have remained stagnant, at 45 percent and 16 percent, respectively.[19] Additionally, at the “national level almost 40% of these children are underweight...and about 9% [are affected] by wasting”, diseases where muscle and fat tissues degenerate as a result of malnutrition.[20] Similarly, women are also at risk, with about half suffering from anemia, which is commonly caused by iron deficiency.[21]

A significant contributing factor to this issue is food insecurity; The World Food Programme estimates that nearly one in two Pakistanis are at risk of food insecurity.[22] This in turn can be attributed in part to the rapid urbanisation and mass migrations caused by the Great Partition of India and Pakistan, and the resulting issues with infrastructure and government, as well as other factors.

For example, contamination of water sources affects water and food security, and also over a long time contribute to stunting and underweight measurements, caused by deficiencies of nutrients, lost through diarrhea, dysentery, and other water-born diseases.[23]

Some limitations to interventions and aid are due to the limitations in peer-reviewed literature on this specific topic. According to the director of the nutritional science program at Pakistan's Dow University of Health Sciences (DUHS), and president of the Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetic Society (PNDS), Dr. Safdar, “only 99 papers of nutritional research were published in Pakistan between 1965 and 2003”.[24]

Smoking

Tobacco smoking in Pakistan is legal, but under certain circumstances is banned. If calculated on per day basis, 177 million cigarettes per day were consumed in FY-14. According to the Pakistan Demographic Health Survey, 46 per cent men and 5.7 per cent women smoke tobacco. The habit is mostly found in the youth of Pakistan [25] and in farmers, and is thought to be responsible for various health problems and deaths in the country. Smoking produces many health problems in smokers. Pakistan has the highest consumption of tobacco in South Asia.

Drug addiction

In the last few decades, drug addiction has increased exponentially in Pakistan. Most of the illegal drugs come from the neighbouring Afghanistan. According to the UN estimate, 8.9 million people in the country are drug users. Cannabis is the most used drug. The rate of injection drug abuse has also increased significantly in Pakistan, sparking fears of an HIV epidemic.

Although, the increase in the problem has been alarming, the government response has been minimal at best. Few programs are active in the country to help drug addicts and smuggling and availability of the drugs in the country has gone almost unchecked.

Anti-Narcotics Force is the government agency responsible for tackling drug smuggling and use within Pakistan.

Suicide

Pakistan's suicide rate is below the worldwide average. The 2015 global rate was 6.1 per 100,000 people (in 2008, 11.6). Suicides represent some 0.9% of all deaths.

Pakistan's death rate, as given by the World Bank, is 7.28 per 1000 people in 2016 (the lowest rate in the 2006-2018 period). In 2015, the suicide rate in Pakistan was approximately 1.4 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, one seventh of the global average. Similarly, suicides represent only ~.1.2% of all deaths.

Cancer

Among Asian countries, Pakistan has the highest rates of breast and ovarian cancer. The genetic findings show that BRCA mutation (BRCA1 and BRCA2) mutations account for a substantial proportion of hereditary breast/ovarian cancer and early-onset breast and ovarian cancer cases in Pakistan.[26] Breast cancer is the most common cancer in Pakistan as different studies show it kills nearly 40,000 women every year.[27] According to World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer rates are getting worse and it is not sparing even younger age group.[28]

Reproductive Health and Rights

Introduction

Reproductive health being stigmatized through sociocultural norms remains one of the most poorly developed segments of health system in Pakistan. According to the United Nations Population Fund unmet access to sexual and reproductive health deprive women of the right to make crucial choices about their bodies and future and affect the family welfare. Poor reproductive health of adolescents leads to early childbearing and parenthood, pregnancy complications, maternal deaths and disability. According to a study of Population Council, Pakistan[29] adolescents and youth in Pakistan are at risk of experiencing poor reproductive health, which has a number of negative implications for adolescents and youth, and for society at large.

Knowledge of Reproductive Health and Rights

Pakistan do not have concrete reproductive health educational programs targeted at young population. Young boys and girls are more aware of their rights as youth but they do not know much about their Reproductive Health Rights. Adolescents and youth face barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services such as needing an elder family member to accompany them. Further country's socio-cultural background discourages the discussion about reproductive health, making it difficult to provide sex education and awareness about sexually transmitted diseases. According to latest Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18 the proportions of young married men and women who have heard about HIV/AIDS or have comprehensive knowledge about it are quite low. Moreover, health facilities predominantly focus on treatment rather than a preventive approach.

| Gender | Age | Percentage |

| Male | 15-19y | 22.3 |

| Female | 15-19y | 13.2 |

| Male | 20-24y | 51.8 |

| Female | 20-24y | 21.5 |

| Male | 25-29y | 63.3 |

| Female | 25-29y | 34.7 |

Health of Adolescent Mothers and their Children

Compared to older mothers, adolescent mothers in Pakistan are three times more likely to be anemic and have a lower pre-pregnancy body mass index.[30] As a result of this, their newborns are more prone to Preterm Birth and low birth weight and have a higher risk of neonatal death.[31]

Pediatric intensive care units are available solely in large cities where the "cost of intensive care is high and affordable only by middle-high income groups."[32] As of 2015, there didn't exist available data on Pakistani critically ill children in PICU.[32]

Family Planning

Although use of contraceptives and other modern contraceptive methods increases in recent years but still Pakistan has a high fertility rate. Level of Family Planning knowledge rises steadily with age, from about 91 percent of women in the 15 to 19 age group to nearly 99 percent among women of 25 to 29 years. But knowledge level varies greatly among different regions of the country where Balochistan and Sindh have the lowest proportion of women with knowledge of contraceptive methods and surprisingly in federally administered tribal areas a very high proportion of women even higher than the Punjab and Islamabad know about at least one contraceptive method.[33]

Mental Health

Introduction

Mental health is mostly neglected in Pakistan, where 10- 16% of the population, more than 14 million, suffers from mild to moderate psychiatric illness. The figures probably do not include a large number of people who have never seen a psychiatrist and who strongly deny the need for psychiatric consultation.[34]

Legislation and Policy

When Pakistan was created in 1947, the newly created state continued with the Lunacy Act of 1912, which had been in place in British India. The focus of the act was more on detention than on treatment and with advances in treatment, especially the introduction of psychotropic medication, updated legislation was needed but it was not until 2001 that the Lunacy Act of 1912 was replaced by the Mental Health Ordinance of 2001.[35] Following the 18th amendment in the constitution of Pakistan, health was made a provincial subject rather than a federal one. On 8 April 2010, the Federal Mental Health Authority was dissolved and responsibilities were devolved to the provinces, and it became their task to pass appropriate mental health legislation through their respective assemblies. Only the provinces of Sindh and Punjab have a mental health act in place and there is an urgent need for similar legislative frameworks in other provinces to protect the rights of those with mental illness.[35]

Pakistan's mental health policy was last revised in 2003.The disaster/emergency preparedness plan for mental health was last revised in 2006.[36] There is no policy that protects the rights of people who get convicted but are mentally ill. Recently, Pakistan's top court has ruled that schizophrenia does not fall within its legal definition of mental disorders, clearing the way for the execution of a mentally ill man convicted of murder.[37][38]

Mental Health Care Services

The allocated mental health budget is 0.4% of total health care expenditures.[39] Estimated mental health spending per capita is (US$) $0.01.[36] There are only 5 mental hospitals in Pakistan.[36]

Number of Mental health outpatient facility 4,356 and number of mental health day-treatment facility is 14.[36] There are 18 NGOs in the country involved in individual assistance activities such as counselling, housing or support groups.[40] The total number of human resources working in mental health facilities or private practices per 100,000 people is 87.023, among which 342 are psychiatrists, meaning that there is roughly one psychiatrist available per 500,000 people. Of these, 45% work for government-run mental health facilities and 51% work with non-governmental organisations and other private institutions, while 4% work in both sectors.[41][34][42]

Disease Burden of Mental Health

Burden of mental disorders in terms of Disability-adjusted life years (per 100,000 population) is 2,430.[36] Common mental health problems have been identified in both the rural and urban population which seems to have a positive association with socioeconomic adversities, relationship problems and lack of social support. Depressive and anxiety disorders appear to be highest, followed by bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosomatic disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.[43]

| MENTAL DISORDERS | DALYS |

| Schizophrenia | 0.36% |

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.47% |

| Drug use disorders | 0.70% |

| Depressive Disorders | 1.28% |

| Bipolar disorders | 0.27% |

| Anxiety disorders | 0.89% |

| Eating disorders | 0.06% |

| Autistic Spectrum | 0.33% |

| ADHD | 0.01% |

| Conduct disorder | 0.26% |

| Intellectual Disability | 0.21% |

| Other mental disorders. | 0.32% |

Depression often starts at a young age and affects women more commonly than men.[44] One or two mothers out of 10 have depression after childbirth. Depression also limits a mother's capacity to care for her child, and can seriously affect the child's growth and development. A study showed that exposure to maternal mental distress is associated with malnutrition in 9‐month infants in urban Pakistan.[45]

Pakistan is one of those countries where the mental health of children is not taken seriously by parents. As per recent stats published by one news website, almost 36% of people in Pakistan are suffering from anxiety and depression.[46] The major reason for these mental illnesses is bad relationship with friends & family. Moreover, due to the recent pandemic, poverty and unemployment also increases the depression, anxiety, and suicide rate.[47]

Almost 18,000 people in Pakistan commit suicide annually while the number of suicide attempts is almost four times greater than these figures.[48] Suicide prevalence in Pakistan is 9.3 people per 100,000 persons.[36]

According to United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) technical summary report 2012 on drug use in Pakistan, annual prevalence is estimated to be 5.8 per cent, or 6.45 million of the population in Pakistan aged between 15 and 64 used drugs in 2012. Cannabis is the most commonly used drug with an annual prevalence of 3.6 per cent or approximately four million people. Cannabis is followed by sedatives and tranquillisers, such as benzodiazepines, heroin, opium and other opiates.[40]

Challenges and Necessary Actions

The stigma against mental illness is rampant in Pakistan. It is sustained by a popular belief in spiritual cures — exorcising evil spirits, experimenting with herbal cures — and a lack of awareness about mental illness's causes, symptoms, and cures. Even when patients recognize their symptoms, overcome the stigma, gain the support of their families and start looking for medical help, there are insufficient mental healthcare facilities.[49][34]

It is concluded that the health care system's response in Pakistan is not adequate to meet the current challenges and that changes in policy are needed. Mental health care needs to be incorporated as a core service in primary care and supported by specialist services.[43] Political commitment, adequate human and financial resources, and advocacy are needed for the integration of mental health into PHC in Pakistan.[50]

There is a strong need to provide adequate training for general practitioners and postgraduate training for mental health professionals to meet the current demands. A collaborative network between stakeholders in the public and private sector, as well as non-governmental organizations are required that promotes mental health care and advocates for changes in mental health policy.[35][43]

Ongoing Programs

A number of innovative programmes to develop indigenous models of care like the 'Community Mental Health Programme' and 'Schools Mental Health Programme' have been developed by the Pakistan government. These programmes have been found effective in reducing stigma and increase awareness of mental illness amongst the adults and children living in rural areas.[51]

Recently, WHO launched a mental health Gap Action Program (mhGAP). It will call for improving political commitments and help develop policies, and legislative infrastructure, to provide integrated health care.[48]

The British BasicNeeds program, mental health focused international NGO with a global reach spanning 14 countries, began forming partnerships with Pakistani nonprofits in 2013, has already served 12,000 people in need of psychiatric attention. In addition to setting up camps where patients can see doctors, receive prescriptions for medicines and engage in therapy, the program trains citizens to recognise symptoms and side effects of mental illnesses.[52][49]

Resources

| Doctors (PMC-2022) | 274,135 |

| Dentists (PMC-2022) | 32,237 |

| Nurses (2022) | 121,245 |

| Midwives (2022) | 44,693 |

| Lady Health Workers (2022) | 22,408 |

| Registered vets | 10,600 |

| Total Health Facilities | 14,568 | 146,053 beds |

| Hospitals | 1,276 | 105,592 beds |

| Dispensaries | 5,802 | 2,845 beds |

| Rural health centers | 736 | 9,612 beds |

| Tuberculosis Centers | 416 | 184 beds |

| Basic health units | 5,558 | 6,555 beds |

| M.C.H. centers | 906 | 256 beds |

Personnel

According Dr Nasir Javed Malik, there are 274,135 doctors (2022 Statistics from Pakistan Medical Commission) and 14,568 health care facilities in 2021-22 to cater for over 229 million people. Overall, Pakistan’s SDGs Index score has increased from 53.11 in 2015 to 63.5 in 2020 i.e. 19.5 percent up from the baseline of 2015. This is a composite score. There are sectoral achievements at different levels. Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in Pakistan is 54.2 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020, while Neonatal Mortality Rate is 40.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020 from 41.2 in 2019.Maternal Mortality Ratio is 186 maternal deaths per 100,000 births (Pakistan Economic Survey-2021)

Many Pakistani doctors and medical professionals choose to migrate to other countries, contributing to a brain drain and chronic skills shortage in the country. In the United States alone, there are over 20,000 doctors of Pakistani origin.

Challenge of COVID-19 Outbreak In Pakistan : To date, Pakistan has experienced five waves of the pandemic. The Government successfully contained COVID-19 through various initiatives taken under Pakistan Preparedness and Response Plan (PPRP) 2021-22, which is a continuation of the first PPRP, launched on 23 April 2020 in response to the detection of COVID-19 in Pakistan on 26 February 2020. The PPRP 2020, was worth US$595 million. The PPRP 2021-22 highlights the achievements in the implementation of PPRP 2020, the challenges and lessons learned, and the proposed priority intervention to be implemented from June 2021 to July 2022. This plan has been developed by the M/o NHSR&C in consultation with all provinces.

Facilities

- List of hospitals in Pakistan

Professional institutes

As of 2007, there were 48 medical colleges and 21 dental colleges in the country.[53]

- List of schools of medicine in Pakistan

- List of schools of dentistry in Pakistan

- List of schools of pharmacy in Pakistan

- List of schools of nursing in Pakistan

- List of schools of veterinary medicine in Pakistan

Services

Nursing

According to Dr.Shaikh Tanveer Ahmed Nursing is a major component of health care in Pakistan. The topic has been the subject of extensive historical studies,[54] is as of 2009 a major issue in that country,[55] and has been the subject of much scholarly discussion amongst academics and practitioners.[56] In 2009, Pakistan's government stated its intent to improve the country's nursing care.[57]

Dentistry

At present there are upwards of 70 dental schools (public and private) throughout Pakistan, according to the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council the state regulatory body has upwards of 11500 registered dentists. The four-year training culminates in achieving a Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) degree, which requires a further one year compulsory internship to be a registered dentist in Pakistan.

Pharmacy

The pharmaceutical industry in Pakistan has grown during the past recent decades. At the time of the independence of Pakistan in 1947, there were few production units in the country. Currently Pakistan has more than 800 large volume pharmaceutical formulation units, including those operated by 25 multinationals present in the country. Almost all the raw materials used in making of medicine are sourced from abroad. About 50 percent of them are imported from India.

The Pakistan Pharmaceutical Industry meets around 90% of the country's demand of finished dosage forms and 4% of Active ingredients. Specialized finished dosage forms such as soft gelatin capsules, parenteral fat emulsions and Metered-dose inhalers continue to be imported. There are only a few bulk drug Active ingredient producers and Pakistan mainly depends on imports of bulk drugs for its formulation needs resulting in frequent drug shortages. Political disturbances and allegations of under-invoicing add to the uncertainty of imports and clashes with the customs and tax authorities are common.

The National pharma industry has shown growth over the years, particularly over the last decade. The industry is trying to upgrade itself and today the majority industry is following local Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) laws, with a few in accordance with international guidance. Currently the industry has the capacity to manufacture a variety of traditional products ranging from simple pills to capsules, ointments and syrups.

In 2017, World Health Organization accredit first-ever Pakistani drug formulated by Getz Pharma.

Medical tourism

Medical tourism in Pakistan is viewed as an untapped market that could be turned into a huge opportunity if the government "focuses on key issues". According to Pakistani medical experts, Pakistan has a "huge potential" in becoming a regional medical tourism hub, comparable to many other countries in its neighbourhood. Medical tourism in Pakistan has been arranging potential trips for many medical health and care procedures. A number of modern hospital facilities exist in major cities such as Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore that are fully equipped and facilitated with the latest medical technologies. Many doctors and surgeons in Pakistani hospitals tend to be foreign qualified. However, security issues and an overall below-par health infrastructure have challenged the growth of the industry.

Veterinary medicine

Veterinary medicine is widely practiced, both with and without professional supervision. Professional care is most often led by a veterinary physician (also known as a vet, veterinary surgeon or veterinarian), but also by paraveterinary workers such as veterinary nurses or technicians. This can be augmented by other paraprofessionals with specific specialisms such as animal physiotherapy or dentistry, and species relevant roles such as farriers.

Community medicine

Pakistan's government has committed to the goal of making its population healthier, as evidenced by its support for the Social Action Programme (SAP) and by the new vision for health, nutrition, and population outlined in the National Health Policy Guidelines. The National Health Policy provides guidelines to provinces for improving health infrastructure and healthcare services while maintaining the role of the federal government in coordinating key programs such as communicable disease control.[5] Initiated in 1992 by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), the Social Action Programme aims to make advances in four social sectors: primary education, primary health, water supply and sanitation, and family planning.[58] The goals of the program are to reform institutions and increase financing for social services within these sectors. SAP is largely financed by external organizations such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, Government of Netherlands, and Overseas Development Agency of UK.[58]

In 1994, the Government of Pakistan launched the National Programme for Family Planning and Primary Healthcare. The main goal of the program is to provide primary health care to underserved populations, particularly women and children, through family planning services.[3] Since its inception, the program has become one of the largest community health based programs in the world, providing primary healthcare services to 80 million people mostly in rural areas.[59] One of the program's main initiatives, the Lady Health Worker Programme, trains women to serve as community health providers in areas across the country and has turned out to be a promising community-based health worker program. Lady health workers are local, literate women who undergo approximately 15 months of training after recruitment. Once training is complete, the lady health workers serve 100 to 150 homes by visiting 5-7 homes daily.[59] The main responsibilities of lady health workers are to conduct screenings of pregnant women and refer them to clinical services if needed, distribute condoms and contraceptive pills, provide interventions for malnutrition such as nutritional counseling, and treat common diseases with special drug kits.[60][61] There are currently approximately 96,000 women serving as lady health workers. Compared to communities not served by lady health workers, communities with access to this initiative are 11% more likely to use modern family methods, 13% more likely to have a tetanus toxoid vaccination, 15% more likely to receive a medical check-up within 24 hours of birth, and 15% more likely to have immunized children below the age of three years.[62]

Despite the Lady Health Worker Programme's strengths, a study conducted in 2002 in Karachi has shown that many lady health workers feel that their salary is too low and their payment is too irregular.[63] Lady health workers are not classified as permanent government employees and, therefore, do not have government benefits. The contractual nature of their job is a constant threat and source of anxiety. Other possible improvements include skill and career development opportunities for lady health workers and a stronger patient referral system within the program.[63]

Prime Minister National Health Program

Prime Minister's National Health Program was launched on December 31, 2015.[64][65] It was a state-run health insurance program. The main aim of the program is to benefit the Pakistani citizens living under the line of poverty. Federal Health Minister was appointed to monitor the process.

Initially, the program covered 15 districts of the Punjab, Balochistan and the federally administered tribal areas and Islamabad as well.[65] Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Governments declined to become part of this scheme.[65] The free-of-cost treatment was offered for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, Burma and RTA (life and limb saving treatment, implants, prosthesis).[64] It also includes treatment of end-stage renal diseases and dialysis, chronic infections (Hepatitis), organ failure (Hepatic, Renal, Cardiopulmonary) and cancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery).[64]

Until now 3227113 have been enrolled in this program.[66] Furthermore, on January 3, 2018, the program was extended to 38 districts including the Gilgit-Baltistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir along with others.[67]

Emergence of digital healthcare

In the last decade, Pakistan has undergone massive digitization in various sectors of economy. Introduction of 3G/4G technologies, growing internet penetration, and an emerging startup ecosystem have fueled a new wave of innovation. Technology has led to a number of positive changes in healthcare delivery.

Today, Pakistan has over 12 startups that work on various service areas, from service delivery to finding the right doctor. These healthcare companies have not only attracted local audience but also attracted foreign investment.[68] 60 million Pakistanis have a smartphone,[69] and they can avail healthcare information, book appointment with the doctors, order medicines, and request lab tests from their smartphones. This emergence of digital healthcare platforms is making it easy for the people to access the right doctor and enabling them to avail the best healthcare services at their doorsteps.

In recent times, the startup culture in Pakistan has boomed with many players trying to change the healthcare segment as well.[70][71][72][73][74] These startups are helping patients to buy medicines online, order lab tests and get home sample collection done and maintain medical records so that all patient data & history is stored in one place. Beside all these facilities, these startups are also providing the online audio and video consultation services.

See also

- List of medical organizations in Pakistan

- Medical tourism in Pakistan

- Health in Pakistan

- Emergency medical services in Pakistan

- Tuberculosis control programme of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

References

- Javed, Saad Ahmed; Liu, Sifeng (2018-10-08). "Evaluation of outpatient satisfaction and service quality of Pakistan's healthcare projects". Grey Systems: Theory and Application. 8 (4): 462–480. doi:10.1108/gs-04-2018-0018. ISSN 2043-9377.

- Javed, Saad Ahmed; Liu, Sifeng; Mahmoudi, Amin; Nawaz, Muhammad (2018-08-30). "Patients' satisfaction and public and private sectors' health care service quality in Pakistan: Application of grey decision analysis approaches". The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 34 (1): e168–e182. doi:10.1002/hpm.2629. ISSN 0749-6753. PMID 30160783.

- Kurji, Zohra (2016). "Analysis of the Health Care System of Pakistan: Lessons Learnt and Way Forward". Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad. 28 (3): 601–604. PMID 28712245.

- Akbari, Ather (Summer 2009). "Demand for Public Health Care in Pakistan". The Pakistan Development Review. 48 (2): 141–153. doi:10.30541/v48i2pp.141-153.

- Akram, Muhammad (2007). "Health Care Services and Government Spending in Pakistan". Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad: 1–25.

- "WHO Country Cooperation Strategies and Briefs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2007.

- "WHO | Pakistan". WHO. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Shaikh, Babar (2015). "Private Sector in Health Care Delivery: A Reality and Challenge in Pakistan". J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 27 (2): 496–498. PMID 26411151.

- "Pakistan's healthcare system | Pakistan Today". archive.pakistantoday.com.pk. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- Shaikh, Babar (2005). "Health Seeking Behaviour and Health Service Utilization in Pakistan: Challenging the Policy Makers". Journal of Public Health. 27: 49–54. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdh207. PMID 15590705.

- "Pakistan needs 'a million more nurses'". The Express Tribune. 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- "Health expenditure: 1.2pc of GDP against WHO-recommended 5pc". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- "How Much Should Countries Spend on Health?" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2003.

- Cancer in Pakistan

- College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan Journal, Editorial 2007 http://www.cpsp.edu.pk/jcpsp/ARCHIEVE/JCPSP-2007/dec07/Editorial1.pdf

- Asif, Muhammad; Aslam, Muhammad; Altaf, Saima; Atif, Saima; Majid, Abdul (2020-03-30). "Prevalence and Sociodemographic Factors of Overweight and Obesity among Pakistani Adults". Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome. 29 (1): 58–66. doi:10.7570/jomes19039. ISSN 2508-7576. PMC 7118000. PMID 32045513.

- "World Health Organization – Diabetes country profiles" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). 2016.

- "Fighting malnutrition in Pakistan with a helping hand from children abroad". UNICEF. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- "Pakistan | Hunger Relief in Asia | Action Against Hunger". actionagainsthunger.org. 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- "Nutrition country profiles: Pakistan summary". fao.org. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- "Malnutrition in Pakistan severest in region: report". thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- "UN World Food Programme". Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- Azizullah, Azizullah; Khattak, Muhammad Nasir Khan; Richter, Peter; Häder, Donat-Peter (2011). "Water pollution in Pakistan and its impact on public health — A review". Environment International. 37 (2): 479–497. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2010.10.007. PMID 21087795.

- Yusuf, Suhail (2013-07-01). "More research in diet and nutrition urged at symposium". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- Ahmed, Rashid; Rizwan-ur-Rashid, null; McDonald, Paul W.; Ahmed, S. Wajid (November 2008). "Prevalence of cigarette smoking among young adults in Pakistan". The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 58 (11): 597–601. ISSN 0030-9982. PMID 19024129.

- Rashid MU, Zaidi A, Torres D, Sultan F, Benner A, Naqvi B, Shakoori AR, Seidel-Renkert A, Farooq H, Narod S, Amin A, Hamann U (2006). "Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Pakistani breast and ovarian cancer patients". Int J Cancer. 119 (12): 2832–9. doi:10.1002/ijc.22269. PMID 16998791.

- "Pakistan tops deaths from breast cancer in Asia". The Nation. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- "Pakistan has highest incidence of breast cancer in Asia". 25 October 2014.

- Kamran, Iram; Niazi, Rehan; Khan, Kiren; Abbas, Faisal (1 January 2019). "Situation analysis of reproductive health of adolescents and youth in Pakistan". Reproductive Health: 1. doi:10.31899/rh11.1025.

- Mubeen, Kiran; Baig, Marina (2016). "Adolescent Pregnancies: The case of Pakistan". Journal of Asian Midwives. 3 (2): 71.

- Pradhan, Rina; Wynter, Karen; Fisher, Jane (1 September 2015). "Factors associated with pregnancy among adolescents in low-income and lower middle-income countries: a systematic review". J Epidemiol Community Health. 69 (9): 918–924. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-205128. ISSN 0143-005X. PMID 26034047. S2CID 28168041.

- Siddiqui, Naveed-ur-Rehman; Ashraf, Zohaib; Jurair, Humaira; Haque, Anwarul (March 1, 2015). "Mortality patterns among critically ill children in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a developing country". Indian J Crit Care Med. 19 (3): 147–150. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.152756. ISSN 0972-5229. OCLC 5831007146. PMC 4366912. PMID 25810609. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- Kamran, Iram; Niazi, Rehan; Khan, Kiren; Abbas, Faisal (1 January 2019). "Situation analysis of reproductive health of adolescents and youth in Pakistan". Reproductive Health: 15. doi:10.31899/rh11.1025.

- Bashir, Aliya (June 1, 2018). "The state of mental health care in Pakistan". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (6): P471. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30191-3. PMID 29857845.

- Amina, Tareen (1 August 2016). "The mental health law in Pakistan". BJPsych International. 13 (3): 67–69. doi:10.1192/S2056474000001276. PMC 5618880. PMID 29093907.

- "WHO Mental health Atlas country profile 2014" (PDF).

- "Schizophrenia not a mental illness, Pakistan's Supreme Court says". 21 October 2016.

- "Ignoring Mental Illness is Among Pakistan's Misplaced Priorities".

- Muhammad Gadit, Amin A. "Is there a visible mental health policy in Pakistan?". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association.

- Routledge Handbook of Psychiatry in Asia.

- "50 million people with mental disorders in Pakistan'". 9 October 2016.

- "WHO Report on mental health system in Pakistan" (PDF).

- Khalily, Muhammad Tahir (2011). "Mental health problems in Pakistani society as a consequence of violence and trauma: a case for better integration of care". Int J Integr Care. 11 (4): e128. doi:10.5334/ijic.662. PMC 3225239. PMID 22128277.

- "Women and depression". Harvard Health. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- Rahman, A. (15 December 2003). "Mothers' mental health and infant growth: a case control study from Rawalpindi, Pakistan". Child: Care, Health and Development. 30 (1): 21–27. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00382.x. PMID 14678308.

- "Disturbing facts about mental health in Pakistan | Political Economy | thenews.com.pk". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Mamun, Mohammed A.; Ullah, Irfan (2020). "COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty? – The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 87: 163–166. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. ISSN 0889-1591. PMC 7212955. PMID 32407859.

- "World Health Day promoting mental health in global development agenda". 8 September 2018.

- "Pakistan's mental health problem". 7 October 2015.

- Hussain, Syed S. (2018). "Integration of mental health into primary healthcare: Perceptions of stakeholders in Pakistan". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 24 (2): 146–153. doi:10.26719/2018.24.2.146. PMID 29748943. S2CID 13670847.

- S., Karim (2004). "Pakistan mental health country profile". Int Rev Psychiatry. 16 (1–2): 83–92. doi:10.1080/09540260310001635131. PMID 15276941. S2CID 38383892.

- "Basic Needs".

- "Health facts". Ministry of Health, Pakistan. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- History of Nursing in Pakistan search at Google. Accessed December 10, 2009.

- "Nursing in Pakistan" search at Google. Accessed December 10, 2009.

- "Nursing in Pakistan" search at Google Scholar. Accessed December 10, 2009.

- "Press Information Department". Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- Candland, Christopher (2001). Institutional Impediments to Human Development in Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 264–283.

- Wazir, Mohammad (2013). "National Program for Family Planning and Primary Health Care Pakistan: a SWOT Analysis". Reproductive Health. 10 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-10-60. PMC 3842797. PMID 24268037.

- Farooq, Shujaat; Durr-E-Nayab; Arif, G. M. (2014-06-01). "Welfare Impact of the Lady Health Workers Programme in Pakistan". The Pakistan Development Review. 53 (2): 119–143. doi:10.30541/v53i2pp.119-143. ISSN 0030-9729.

- Khan, Ayesha (July 2011). "Lady Health Workers and Social Change in Pakistan". Economic and Political Weekly. 46: 28–31.

- "External Evaluation of the National Programme for Family Planning and Primary Health" (PDF). Oxford Policy Management. 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- Afsar, Habib (2005). "Recommendations to strengthen the role of lady health workers in the national program for family planning and primary health care in Pakistan: the health workers perspective". Journal of Ayub Medical College. 17 (1): 48–53. PMID 15929528.

- "PM launches National Health Programme". Tribune. December 31, 2015.

- Junaidi, Ikram (2016-01-01). "PM launches health scheme for the poor". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- "Index of /". pmhealthprogram.gov.pk. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- Junaidi, Ikram (2018-01-03). "PM's health programme to cover 15 more districts". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- "MyDoctor.pk raises $1.1million funding, rebrands to oladoc.com". Pakistan Today. 21 February 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Telecom Indicators". pta.gov.pk. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Find doctors with mobile app 'Marham' in Pakistan". Propakistani. June 29, 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "MyDoctor.pk raises $1.1 million in funding from Glowfish Capital". Business Recorder. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "MyDoctor.pk raises $1.1million funding, rebrands to oladoc.com". Pakistan Today. February 21, 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Sehat Kahani, a startup aiming to empower female doctors across Pakistan, raises $500,000 in seed funding". Dawn. March 24, 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Pakistan's Healthwire closes $700,000 investment for its digital healthcare platform". October 6, 2020.