Immunoglobulin G

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation.[1] IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG antibody has two paratopes.

Function

Antibodies are major components of humoral immunity. IgG is the main type of antibody found in blood and extracellular fluid, allowing it to control infection of body tissues. By binding many kinds of pathogens such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, IgG protects the body from infection.

It does this through several mechanisms:

- IgG-mediated binding of pathogens causes their immobilization and binding together via agglutination; IgG coating of pathogen surfaces (known as opsonization) allows their recognition and ingestion by phagocytic immune cells leading to the elimination of the pathogen itself;

- IgG activates all the classical pathway of the complement system, a cascade of immune protein production that results in pathogen elimination;

- IgG also binds and neutralizes toxins;

- IgG also plays an important role in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and intracellular antibody-mediated proteolysis, in which it binds to TRIM21 (the receptor with greatest affinity to IgG in humans) in order to direct marked virions to the proteasome in the cytosol;[2]

- IgG is also associated with type II and type III hypersensitivity reactions.

IgG antibodies are generated following class switching and maturation of the antibody response, thus they participate predominantly in the secondary immune response. [3]

IgG is secreted as a monomer that is small in size allowing it to easily perfuse tissues. It is the only antibody isotype that has receptors to facilitate passage through the human placenta, thereby providing protection to the fetus in utero. Along with IgA secreted in the breast milk, residual IgG absorbed through the placenta provides the neonate with humoral immunity before its own immune system develops. Colostrum contains a high percentage of IgG, especially bovine colostrum. In individuals with prior immunity to a pathogen, IgG appears about 24–48 hours after antigenic stimulation.

Therefore, in the first six months of life, the newborn has the same antibodies as the mother and the child can defend itself against all the pathogens that the mother encountered in her life (even if only through vaccination) until these antibodies are degraded. This repertoire of immunoglobulins is crucial for the newborns who are very sensitive to infections, especially within the respiratory and digestive systems.

IgG are also involved in the regulation of allergic reactions. According to Finkelman, there are two pathways of systemic anaphylaxis:[4][5] antigens can cause systemic anaphylaxis in mice through classic pathway by cross-linking IgE bound to the mast cell receptor FcεRI, stimulating the release of both histamine and platelet activating factor (PAF). In the alternative pathway antigens form complexes with IgG, which then cross-link macrophage receptor FcγRIII and stimulates only PAF release.[4]

IgG antibodies can prevent IgE mediated anaphylaxis by intercepting a specific antigen before it binds to mast cell–associated IgE. Consequently, IgG antibodies block systemic anaphylaxis induced by small quantities of antigen but can mediate systemic anaphylaxis induced by larger quantities.[4]

Structure

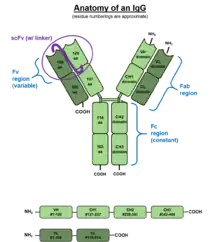

IgG antibodies are large globular proteins with a molecular weight of about 150 kDa made of four peptide chains.[6] It contains two identical γ (gamma) heavy chains of about 50 kDa and two identical light chains of about 25 kDa, thus a tetrameric quaternary structure.[7] The two heavy chains are linked to each other and to a light chain each by disulfide bonds. The resulting tetramer has two identical halves, which together form the Y-like shape. Each end of the fork contains an identical antigen binding site. The various regions and domains of a typical IgG are depicted in the figure to the left. The Fc regions of IgGs bear a highly conserved N-glycosylation site at asparagine 297 in the constant region of the heavy chain.[8] The N-glycans attached to this site are predominantly core-fucosylated biantennary structures of the complex type.[9] In addition, small amounts of these N-glycans also bear bisecting GlcNAc and α-2,6-linked sialic acid residues.[10] The N-glycan composition in IgG has been linked to several autoimmune, infectious and metabolic diseases.[11]

Subclasses

There are four IgG subclasses (IgG1, 2, 3, and 4) in humans, named in order of their abundance in serum (IgG1 being the most abundant). [12]

| Name | Percentage | Crosses placenta easily | Complement activator | Binds to Fc receptor on phagocytic cells | Half life[13] |

| IgG1 | 66% | yes (1.47)* | second-highest | high affinity | 21 days |

| IgG2 | 23% | no (0.8)* | third-highest | extremely low affinity | 21 days |

| IgG3 | 7% | yes (1.17)* | highest | high affinity | 7 days |

| IgG4 | 4% | yes (1.15)* | no | intermediate affinity | 21 days |

| * Quota cord/maternity concentrations blood. Based on data from a Japanese study on 228 mothers.[14] | |||||

Note: IgG affinity to Fc receptors on phagocytic cells is specific to individual species from which the antibody comes as well as the class. The structure of the hinge regions (region 6 in the diagram) contributes to the unique biological properties of each of the four IgG classes. Even though there is about 95% similarity between their Fc regions, the structure of the hinge regions is relatively different.

Given the opposing properties of the IgG subclasses (fixing and failing to fix complement; binding and failing to bind FcR), and the fact that the immune response to most antigens includes a mix of all four subclasses, it has been difficult to understand how IgG subclasses can work together to provide protective immunity. In 2013, the Temporal Model of human IgE and IgG function was proposed.[15] This model suggests that IgG3 (and IgE) appear early in a response. The IgG3, though of relatively low affinity, allows IgG-mediated defences to join IgM-mediated defences in clearing foreign antigens. Subsequently, higher affinity IgG1 and IgG2 are produced. The relative balance of these subclasses, in any immune complexes that form, helps determine the strength of the inflammatory processes that follow. Finally, if antigen persists, high affinity IgG4 is produced, which dampens down inflammation by helping to curtail FcR-mediated processes.

The relative ability of different IgG subclasses to fix complement may explain why some anti-donor antibody responses do harm a graft after organ transplantation.[16]

In a mouse model of autoantibody mediated anemia using IgG isotype switch variants of an anti erythrocytes autoantibody, it was found that mouse IgG2a was superior to IgG1 in activating complement. Moreover, it was found that the IgG2a isotype was able to interact very efficiently with FcgammaR. As a result, 20 times higher doses of IgG1, in relationship to IgG2a autoantibodies, were required to induce autoantibody mediated pathology.[17] Since mouse IgG1 and human IgG1 are not entirely similar in function, and the inference of human antibody function from mouse studies must be done with great care. However, both human and mouse antibodies have different abilities to fix complement and to bind to Fc receptors.

Role in diagnosis

The measurement of immunoglobulin G can be a diagnostic tool for certain conditions, such as autoimmune hepatitis, if indicated by certain symptoms.[18] Clinically, measured IgG antibody levels are generally considered to be indicative of an individual's immune status to particular pathogens. A common example of this practice are titers drawn to demonstrate serologic immunity to measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), hepatitis B virus, and varicella (chickenpox), among others.[19]

Testing of IgG is not indicated for diagnosis of allergy, and there is no evidence that it has any relationship to food intolerances.[20][21][22]

See also

- Epitope

- IgG4-related disease

References

- Vidarsson, Gestur; Dekkers, Gillian; Rispens, Theo (2014). "IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 520. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4202688. PMID 25368619.

- Mallery DL, McEwan WA, Bidgood SR, Towers GJ, Johnson CM, James LC (2010). "Antibodies mediate intracellular immunity through tripartite motif-containing 21 (TRIM21)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 107 (46): 19985–19990. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10719985M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014074107. PMC 2993423. PMID 21045130.

- Vidarsson, Gestur; Dekkers, Gillian; Rispens, Theo (2014). "IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 520. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4202688. PMID 25368619.

- Finkelman, Fred D. (September 2007). "Anaphylaxis: Lessons from mouse models". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 120 (3): 506–515. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.033. PMID 17765751.

- Khondoun MV, Strait R, Armstrong L, Yanase N, Finkelman FD (2011). "Identification of markers that distinguish IgE-from IgG mediated anaphylaxis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 108 (30): 12413–12418. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10812413K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1105695108. PMC 3145724. PMID 21746933.

- Janeway CA Jr; Travers P; Walport M; et al. (2001). "Ch3 Antigen Recognition by B-Cell and T-cell Receptors". Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease (5th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

- "Antibody Basics". Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- Cobb, Brian A. (2019-08-27). "The History of IgG Glycosylation and Where We Are Now". Glycobiology. 30 (4): 202–213. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwz065. ISSN 1460-2423. PMC 7109348. PMID 31504525.

- Parekh, R. B.; Dwek, R. A.; Sutton, B. J.; Fernandes, D. L.; Leung, A.; Stanworth, D.; Rademacher, T. W.; Mizuochi, T.; Taniguchi, T.; Matsuta, K. (1–7 August 1985). "Association of rheumatoid arthritis and primary osteoarthritis with changes in the glycosylation pattern of total serum IgG". Nature. 316 (6027): 452–457. Bibcode:1985Natur.316..452P. doi:10.1038/316452a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 3927174.

- Stadlmann J, Pabst M, Kolarich D, Kunert R, Altmann F (2008). "Analysis of immunoglobulin glycosylation by LC-ESI-MS of glycopeptides and oligosaccharides". Proteomics. 8 (14): 2858–2871. doi:10.1002/pmic.200700968. PMID 18655055. S2CID 22821543.

- de Haan, Noortje; Falck, David; Wuhrer, Manfred (2019-07-08). "Monitoring of Immunoglobulin N- and O-glycosylation in Health and Disease". Glycobiology. 30 (4): 226–240. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwz048. ISSN 1460-2423. PMC 7225405. PMID 31281930.

- Vidarsson, Gestur; Dekkers, Gillian; Rispens, Theo (2014). "IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 520. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00520. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4202688. PMID 25368619.

- Bonilla FA Immuno Allergy Clin N Am 2008; 803–819

- Hashira S, Okitsu-Negishi S, Yoshino K (August 2000). "Placental transfer of IgG subclasses in a Japanese population". Pediatrics International. 42 (4): 337–342. doi:10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01245.x. PMID 10986861. S2CID 24750352.

- Collins, Andrew M.; Katherine J.L. Jackson (2013-08-09). "A temporal model of human IgE and IgG antibody function". Frontiers in Immunology. 4: 235. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00235. PMC 3738878. PMID 23950757.

- Gao, ZH; McAlister, VC; Wright Jr., JR; McAlister, CC; Peltekian, K; MacDonald, AS (2004). "Immunoglobulin-G subclass antidonor reactivity in transplant recipients". Liver Transplantation. 10 (8): 1055–1059. doi:10.1002/lt.20154. PMID 15390333.

- Azeredo da Silveira S, Kikuchi S, Fossati-Jimack L, Moll T, Saito T, Verbeek JS, Botto M, Walport MJ, Carroll M, Izui S (2002-03-18). "Complement activation selectively potentiates the pathogenicity of the IgG2b and IgG3 isotypes of a high affinity anti-erythrocyte autoantibody". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 195 (6): 665–672. doi:10.1084/jem.20012024. PMC 2193744. PMID 11901193.

- Lakos G, Soós L, Fekete A, Szabó Z, Zeher M, Horváth IF, Dankó K, Kapitány A, Gyetvai A, Szegedi G, Szekanecz Z (Mar–Apr 2008). "Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody isotypes in rheumatoid arthritis: association with disease duration, rheumatoid factor production and the presence of shared epitope". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 26 (2): 253–260. PMID 18565246. Archived from the original on 2014-12-11. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- Teri Shors (August 2011). "Ch5 Laboratory Diagnosis of Viral Diseases and Working with Viruses in the Research Laboratory". Understanding Viruses (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-7637-8553-6.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- Cox L, Williams B, Sicherer S, Oppenheimer J, Sher L, Hamilton R, Golden D (2008). "Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 101 (6): 580–592. doi:10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60220-7. PMID 19119701.

- Stapel, Steven O.; Asero, R.; Ballmer-Weber, B. K.; Knol, E. F.; Strobel, S.; Vieths, S.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; EAACI Task Force (July 2008). "Testing for IgG4 against foods is not recommended as a diagnostic tool: EAACI Task Force Report". Allergy. 63 (7): 793–796. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01705.x. ISSN 1398-9995. PMID 18489614. S2CID 14061223.