Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MON, MRONJ) is progressive death of the jawbone in a person exposed to a medication known to increase the risk of disease, in the absence of a previous radiation treatment. It may lead to surgical complication in the form of impaired wound healing following oral and maxillofacial surgery, periodontal surgery, or endodontic therapy.[1]

| Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw | |

|---|---|

| Other names | MON of the jaw, Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), Medication-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw (MIONJ), Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) (formerly) |

| |

| Specialty | Oral and maxillofacial surgery |

| Symptoms | Exposed bone after extraction, pain |

| Complications | Osteomyelitis of the jaw |

| Usual onset | After dental extractions |

| Duration | Variable |

| Types | Stage 1-Stage 3 |

| Causes | Medications related to cancer therapy, and osteoporosis in combination with dental surgery |

| Risk factors | Duration of anti-resorptive or anti-angiogenic drugs, intravenous vs by-mouth |

| Diagnostic method | Exposed bone >8 weeks |

| Differential diagnosis | Osteomyelitis, Osteoradionecrosis |

| Prevention | No definitive. Drug holiday for some patients. |

| Treatment | antibacterial rinses, antibiotics, removal exposed bone |

| Prognosis | good |

| Frequency | 0.2% for those on biphosphonate type drugs >4 years |

Particular medications can result in MRONJ, a serious but uncommon side effect in certain individuals. Such medications are frequently used to treat diseases that cause bone resorption such as osteoporosis, or to treat cancer. The main groups of drugs involved are anti-resorptive drugs, and anti-angiogenic drugs.

This condition was previously known as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BON or BRONJ) because osteonecrosis of the jaw correlating with bisphosphonate treatment was frequently encountered, with its first incident occurring in 2003.[2][3][4][5] Osteonecrotic complications associated with denosumab, another antiresorptive drug from a different drug category, were soon determined to be related to this condition. Newer medications such as anti-angiogenic drugs have been potentially implicated causing a very similar condition and consensus shifted to refer to the related conditions as MRONJ; however, this has not been definitively demonstrated.[4]

There is no known prevention for bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw.[6] Avoiding the use of bisphosphonates is not a viable preventive strategy on a general-population basis because the medications are beneficial in the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis (including prevention of bony fractures) and treatment of bone cancers. Current recommendations are for a 2-month drug holiday prior to dental surgery for those who are at risk (intravenous drug therapy, greater than 4 years of by-mouth drug therapy, other factors that increase risk such as steroid therapy).[7]

It usually develops after dental treatments involving exposure of bone or trauma, but may arise spontaneously. Patients who develop MRONJ may experience prolonged healing, pain, swelling, infection and exposed bone after dental procedures, though some patients may have no signs/symptoms.[8]

Definition

According to the updated 2014 AAOMS position paper (modified from 2009), in order to distinguish MRONJ, the working definition claims patients may be considered to have MRONJ if all the following characteristics are present:

- 1. Current or previous treatment with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agents.

- 2. Exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for longer than 8 weeks.

- 3. No history of radiation therapy to the jaws or obvious metastatic disease to the jaws.[7]

Osteonecrosis, or localized death of bone tissue, of the jaws, is a rare potential complication in cancer patients receiving treatments including radiation, chemotherapy, or in patients with tumors or infectious embolic events. In 2003,[9][10] reports surfaced of the increased risk of osteonecrosis in patients receiving these therapies concomitant with intravenous bisphosphonate.[11] Matrix metalloproteinase-2 may be a candidate gene for bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws, since it is the only gene known to be associated with both bone abnormalities and atrial fibrillation, another side effect of bisphosphonates.[12]

In response to the growing base of literature on this association, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a broad drug class warning of this complication for all bisphosphonates in 2005.[13]

Signs and symptoms

Classically, MRONJ will cause an ulcer or areas of necrotic bone for weeks, months, or even years following a tooth extraction.[14] While the exposed, dead bone does not cause symptoms these areas often have mild pain from the inflammation of the surrounding tissues.[15] Clinical signs and symptoms associated with, but not limited to MRONJ, include:

- Jaw pain and neuropathy[16]

- Loose teeth[17]

- Mucosal swelling[17]

- Erythema

- Suppuration[17]

- Soft tissue ulceration[17] persisting for more than 8 weeks[18]

- Trismus[17]

- Non-healing extraction sockets[17]

- Paraesthesia or numbness in the jaw[19]

- Bad breath

- Exposed necrotic jaw bone[15]

Cause

Cases of MRONJ have also been associated with the use of the following two intravenous and three oral bisphosphonates, respectively: zoledronic acid and pamidronate and alendronate, risedronate, and ibandronate.[20][21] Despite the fact that it remains vague as to what the actual cause is, scientists and doctors believe that there is a correlation between the necrosis of the jaw and time of exposure to bisphosphonates.[22] Causes are also thought to be related to bone injury in patients using bisphosphonates as stated by Remy H Blanchaert in an article about the matter.

Risk factors

The overwhelming majority of MRONJ diagnoses, however, were associated with intravenous administration of bisphosphonates (94%). Only the remaining 6% of cases arose in patients taking bisphosphonates orally.[6]

Although the total United States prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates exceeded 30 million in 2006, less than 10% of MRONJ cases were associated with patients taking oral bisphosphonate drugs.[23] Studies have estimated that BRONJ occurs in roughly 20% of patients taking intravenous zoledronic acid for cancer therapy and in between 0–0.04% of patients taking orally administered bisphosphonates.[24]

Owing to prolonged embedding of bisphosphonate drugs in the bone tissues, the risk for MRONJ is elevated even after stopping the administration of the medication for several years.[25]

Patients who stopped taking anti-angiogenic drugs are exposed to the same risk as patients who have never taken the drugs because anti-angiogenic drugs do not normally reside in the body for a long period of time.[8]

Risk factors include:[8]

- Dental treatment (e.g. dentoalveolar surgery/procedure that impacts bone) – it is possible for MRONJ to occur spontaneously without any recent invasive dental treatment

- Duration of bisphosphonate drug therapy – increased risk with increased cumulative dose of drug

- Other concurrent medication – use of chronic systemic glucocorticoid increases risk when they are taken in combination with anti-resorptive drugs

- Dental implants

- Drug holidays – no evidence to support a reduction in MRONJ risk if patients stop taking bisphosphonates temporarily/permanently, as drugs can persist in skeletal tissues for many years

- Treatment in the past with anti-resorptive/anti-angiogenic drugs

- Patient being treated for cancer – higher risk

- Patients being treated for osteoporosis/non-malignant bone diseases (e.g. Paget's disease) – lower risk

Research findings

‘The risk of MRONJ after dental extraction was significantly higher in patients treated with ARD (antiresorptive drugs) for oncological reasons (3.2%) than in those treated with ARD for OP (osteoporosis) (0.15%) (p < 0.0001). Dental extraction performed with adjusted extraction protocols decreased MRONJ development significantly. Potential risk indicators such as concomitant medications and pre-existing osteomyelitis were identified.’[26]

Patient risk categories

Low:[8]

- Treatment of osteoporosis or non-malignant bone disease with oral bisphosphonates for <5 years (not taking systemic glucocorticoids)

- Treatment of osteoporosis or non-malignant bone disease with quarterly/yearly infusions of intravenous bisphosphonates for <5 years (not taking systemic glucocorticoids)

- Treatment of osteoporosis or non-malignant bone disease with denosumab (not taking systemic glucocorticoids)

High:

- Patients being treated for osteoporosis or non-malignant bone disease with oral bisphosphonates/quarterly or yearly infusions of intravenous bisphosphonates for >5 years

- Patients being treated for osteoporosis or non-malignant bone disease with bisphosphonates/denosumab for any length of time as well as being treated with systemic glucocorticoids

- Patients being treated with anti-resorptive/anti-angiogenic drugs/both as part of cancer management

- Previous MRONJ diagnosis

"N.B. Patients who have taken bisphosphonate drugs at any time in the past and those who have taken denosumab in the last nine months are allocated to a risk group as if they are still taking the drug."[8]

Anti-resorptive drugs

Anti-resorptive drugs inhibit osteoclast differentiation and function, slowing down the breakdown of bone.[27] They are usually prescribed for patients with osteoporosis or other metastatic bone diseases, such as Paget's disease, osteogenesis imperfecta and fibrous dysplasia.[28][29]

The two main types of anti-resorptive drugs are bisphosphonate and denosumab. These drugs help to decrease the risk of bone fracture and bone pain.

Because the mandible has a faster remodeling rate compared to other bones in the body, it is more affected by the effects of these drugs.[30]

- Bisphosphonate

- Bisphosphonates are either administrated orally or intravenously. They reduces bone resorption.[31]

- Mechanism of action: Bisphosphonate binds to the mineral component of the bone and inhibits enzymes (i.e. farnesyl-pyrophosphate synthase) responsible for bone formation, osteoclast recruitment and osteoclast function.[29][31]

- This type of drug has a high affinity for hydroxyapatite[28] and stays in bone tissue for a long period of time,[29] with alendronate, it has a half-life of approximately ten years.[30]

- The risk of a patient having MRONJ after discontinuing this medication is unknown.[30]

- There are suggestions that bisphosphonate may inhibit the proliferation of soft tissue cells and increases apoptosis. This may result in delayed soft tissue healing.[30]

- Examples of bisphosphonates: : Zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa), Risedronate (Actonel), Alendronate (Fosamax), Etidronate (Didronel), Ibandronate (Boniva), Pamidronate (Aredia), Tiludronate (Skelid).[32]

- Denosumab

- Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody[33][34] which is administrated subcutaneously. It inhibits osteoclast differentiation and activation, reduces bone resorption, improves bone density and lessens skeletal-related events associated with metastasis.[31]

- Mechanism of action: The drug binds to receptor activator nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL), preventing the interaction with RANK.[33][31][34]

- It does not bind to bone and its effect on bone diminishes in 9 months.[30]

Anti-angiogenic drugs

Osteonecrosis of the jaw has been identified as one of the possible complications of taking anti-angiogenic drugs; the association of the disease with the medication is known as MRONJ. This has been stated in the Drug Safety Updates by the MHRA.[8]

Angiogenesis inhibitors interfere with blood vessel formation by interfering with the angiogenesis signalling cascade. They are used primarily to treat cancer. These cancer-fighting agents tend to hinder the growth of blood vessels that supply the tumour, rather than killing tumour cells directly.[35] They prevent the tumour from growing. For example, bevacizumab/aflibercept is a monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), preventing VEGF from binding to receptors on the surface of normal endothelial cells.[36] Sunitinib is a different example of an anti-angiogenic drug; it inhibits cellular signalling by targeting multiple receptor tyrosine kinases. It reduces the blood supply to the tumour by inhibiting new blood vessel formation in the tumor.[37] The tumour may stop growing or even shrink.[38]

Pathogenesis

Although the methods of action are not yet completely understood, it is hypothesized that medication-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw is related to a defect in jaw bone healing and remodelling.

The inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and function, precipitated by drug therapy, leads to decreased bone resorption and remodelling.[31][39] Evidence also suggests bisphosphonates induce apoptosis of osteoclasts.[40] Another suggested factor is inhibition of angiogenesis due to bisphosphonates; this effect remains uncertain.[41][42][43] Several studies have proposed that bisphosphonates cause excessive reduction of bone turnover, resulting in a higher risk of bone necrosis when repair is needed.[44][45][46]

It is also thought that bisphosphonates bind to osteoclasts and interfere with the remodeling mechanism in bone. To be more specific, the drug interferes with the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway through the inhibition of farnesyl diphosphate synthase. Over time, the cytoskeleton of the osteoclasts loses its function and the essential border needed for bone resorption does not form.[7] Like aminobisphosphonates, bisphosphonates have shown to have antiangiogenic properties. Therefore, effects include an overall decrease in bone recycling/turnover as well as an increased inhibition of the absorptive bone abilities.

One theory is that because bisphosphonates are preferentially deposited in bone with high turnover, it is possible that the levels of bisphosphonate within the jaw are selectively elevated. To date, there have been no reported cases of bisphosphonate-associated complications within bones outside the craniofacial skeleton.[13]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw relies on three criteria:[6]

- the patient possesses an area of exposed bone in the jaw persisting for more than 8 weeks,

- the patient must present with no history of radiation therapy to the head and neck

- the patient must be taking or have taken bisphosphonate medication.

According to the updated 2009 BRONJ Position Paper published by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, both the potency of and the length of exposure to bisphosphonates are linked to the risk of developing bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw.[47]

In the 2014 AAOMS update[7] on MRONJ, a staging and treatment strategies table was created:

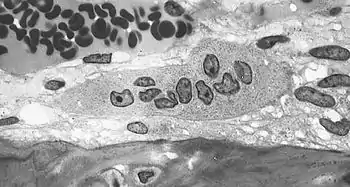

| MRONJ Staging | Criteria* (>8 weeks) | Treatment Strategies** | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|

| At risk | No apparent necrotic bone in patients who have been treated with either oral or IV bisphosphonates | No treatment indicated, Patient education | N/A |

| Stage 0 | No clinical evidence of necrotic bone, but non-specific clinical findings, radiographic changes and symptoms | Systemic management, including the use of pain medication and antibiotics | N/A |

| Stage 1 | Exposed and necrotic bone, or fistulae that probes to bone, in patients who are asymptomatic and have no evidence of infection | Antibacterial mouth rinse, Clinical follow-up on a quarterly basis, Patient education and review of indications for continued bisphosphonate therapy |  |

| Stage 2 | Exposed and necrotic bone, or fistulae that probes to bone, associated with infection as evidenced by pain and erythema in the region of the exposed bone with or without purulent drainage | Symptomatic treatment with oral antibiotics, Oral antibacterial mouth rinse, Pain control, Debridement to relieve soft tissue irritation and infection control |  |

| Stage 3 | Exposed and necrotic bone or a fistula that probes to bone in patients with pain, infection, and one or more of the following: exposed and necrotic bone extending beyond the region of alveolar bone,(i.e., inferior border and ramus in the mandible, maxillary sinus and zygoma in the maxilla) resulting in pathologic fracture, extra-oral fistula, oral antral/oral nasal communication, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border of the mandible of sinus floor | Antibacterial mouth rinse, Antibiotic therapy and pain control, Surgical debridement/resection for longer term palliation of infection and pain |   |

Prevention

Tooth extraction is the major risk factor for development of MRONJ. Prevention including the maintenance of good oral hygiene, comprehensive dental examination and dental treatment including extraction of teeth of poor prognosis and dentoalveolar surgery should completed prior to commencing any medication which is likely to cause osteonecrosis (ONJ). Patients with removable prostheses should be examined for areas of mucosal irritation. Procedures which are likely to cause direct osseous trauma, e.g. tooth extraction, dental implants, complex restoration, deep root planning, should be avoided in preference of other dental treatments. There are limited data to support or refute the benefits of a drug holiday for osteoporotic patients receiving antiresorptive therapy. However, a theoretical benefit may still apply for those patients with extended exposure histories (>4 yr), and current recommendations are for a 2 month holiday for those at risk.[7] There was low quality evidence suggesting taking antibiotics prior to the dental extraction, as well as the use of post operative techniques for wound closure lowered the risk of patients developing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw compared with the usual standard care received for regular dental extractions. Post operative wound closure has been suggested to prevent the contamination of the underlying bone. More evidence is needed to assess the use of antibiotics prior to treatment and the use of wound closure to prevent contamination of the bone, as the quality of evidence evaluated was low.[49]

Patients may be advised to limit alcohol consumption, stop smoking, and practice good dental hygiene. It is also advised for individuals who take bisphosphonates to never allow the tablet to dissolve in the mouth as this causes damage to the oral mucosa.

Management

Treatment usually involves antimicrobial mouth washes and oral antibiotics to help the immune system fight the attendant infection, and it also often involves local resection of the necrotic bone lesion. Many patients with MRONJ have successful outcomes after treatment, meaning that the local osteonecrosis is stopped, the infection is cleared, and the mucosa heals and once again covers the bone.

The treatment the person receives depends on the severity of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Conservative

Indicated in patients who have evidence of exposed bone but no evidence of infection. It may not necessarily eliminate all the lesions, but it may provide patients with long term relief. This approach involves a combination of antiseptic mouthwashes and analgesics and the use of teriparatide.[50] Splints may be used to protect sites of exposed necrotic bone.

Non-surgical

Indicated for people with exposed bone with symptoms of infection. This treatment modality may also be utilised for patients with other co-morbidities which precludes invasive surgical methods. This approach requires antimicrobial mouthwashes, systemic antibiotics and antifungal medication and analgesics.[51]

Surgery

Surgical intervention is indicated in patients with symptomatic exposed bone with fistula formation and one or more of the following: exposed and necrotic bone extending beyond the alveolar bone resulting in pathological fracture; extra-oral fistula; oral antral communication or osteolysis extending from the inferior border of the mandible or the sinus floor. Surgical management involves necrotic bone resection, removal of loose sequestra of necrotic bone and reconstructive surgery. The objective of surgical management is to eliminate areas of exposed bone to prevent the risk of further inflammation and infection. The amount of surgical debridement required remains controversial.

Other

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

- Ultrasonic therapy[52][53]

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used to treat cases involving infections. Penicillin is the first line of choice, although if this is contraindicated commonly used antimicrobials are: clindamycin, fluoroquinolones and/or metronidazole.

Intravenous antibiotics may be used if the infection resists oral treatment. However, there is little evidence of intravenous antibiotics being more efficacious than other methods of treatment.[54]

Epidemiology

The likelihood of this condition developing varies widely from less than 1/10,000 to 1/100, as many other factors need to be considered, such as the type, dose and frequency of intake of drug, how long it has been taken for, and why it has been taken.[55]

In patients taking drugs for cancer, the likelihood of MRONJ development varies from 0 - 12%. This again, varies with the type of cancer, although prostate cancer and multiple myeloma are reported to be at a higher risk.[8]

In patients taking oral drugs for osteoporosis, the likelihood of MRONJ development varies from 0 - 0.2%.[7]

See also

- C-terminal telopeptide, commonly known as CTX, a serum biomarker for bone turnover rate and a tool used to evaluate patient risk for complications due to BRONJ

- Osteonecrosis of the jaw, see section on Bisphosphonates

- Osteoradionecrosis, a term for osteonecrosis caused by radiotherapy

- Phossy jaw

References

- Nase JB, Suzuki JB (August 2006). "Osteonecrosis of the jaw and oral bisphosphonate treatment". Journal of the American Dental Association. 137 (8): 1115–9, quiz 1169–70. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0350. PMID 16873327. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- Marx RE (September 2003). "Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 61 (9): 1115–7. doi:10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. PMID 12966493.

- Migliorati CA (November 2003). "Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 21 (22): 4253–4. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. PMID 14615459.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, O'Ryan F (October 2014). "American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 72 (10): 1938–56. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. PMID 25234529.

- Sigua-Rodriguez EA, da Costa Ribeiro R, de Brito AC, Alvarez-Pinzon N, de Albergaria-Barbosa JR (2014). "Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of the literature". International Journal of Dentistry. 2014: 192320. doi:10.1155/2014/192320. PMC 4020455. PMID 24868206.

- Osteoporosis medications and your dental health pamphlet #W418, American Dental Association/National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2008

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, O'Ryan F (October 2014). "American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 72 (10): 1938–56. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. PMID 25234529.

- "Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw" (PDF). Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. March 2017.

- Marx RE (September 2003). "Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 61 (9): 1115–7. doi:10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00720-1. PMID 12966493.

- Migliorati CA (November 2003). "Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 21 (22): 4253–4. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. PMID 14615459.

- Appendix 11: Expert Panel Recommendation for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw

- Lehrer S, Montazem A, Ramanathan L, Pessin-Minsley M, Pfail J, Stock RG, Kogan R (January 2009). "Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws, bone markers, and a hypothesized candidate gene". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 67 (1): 159–61. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.015. PMID 19070762.

- Ruggiero SL (March 2008). "Bisphosphonate-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws". Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 29 (2): 97–105. PMID 18429424.

- Allen MR, Ruggiero SL (July 2009). "Higher bone matrix density exists in only a subset of patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 67 (7): 1373–7. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.048. PMID 19531405.

- Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, Felsenberg D, McCauley LK, O'Ryan F, et al. (January 2015). "Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 30 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2405. PMID 25414052.

- Zadik Y, Benoliel R, Fleissig Y, Casap N (February 2012). "Painful trigeminal neuropathy induced by oral bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a new etiology for the numb-chin syndrome". Quintessence International. 43 (2): 97–104. PMID 22257870.

- Sharma D, Ivanovski S, Slevin M, Hamlet S, Pop TS, Brinzaniuc K, et al. (January 2013). "Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaw (BRONJ): diagnostic criteria and possible pathogenic mechanisms of an unexpected anti-angiogenic side effect". Vascular Cell. 5 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/2045-824X-5-1. PMC 3606312. PMID 23316704.

- Goodell GG (Fall 2012). "Endodontics: Colleagues for Excellence" (PDF). American Association of Endodontists. 211 E. Chicago Ave., Suite 1100 Chicago, IL 60611-2691: American Association of Endodontists.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Otto S, Hafner S, Grötz KA (March 2009). "The role of inferior alveolar nerve involvement in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 67 (3): 589–92. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.028. PMID 19231785.

- American Dental Association Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Archived 2009-08-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and drug treatments for osteoporosis" (PDF). nos.org.uk. The National Osteoporosis Society.

- Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, Moulopoulos LA, Melakopoulos I, Bozas G, et al. (December 2005). "Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (34): 8580–7. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. PMID 16314620.

- Grbic JT, Landesberg R, Lin SQ, Mesenbrink P, Reid IR, Leung PC, et al. (January 2008). "Incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis in the health outcomes and reduced incidence with zoledronic acid once yearly pivotal fracture trial". Journal of the American Dental Association. 139 (1): 32–40. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0017. PMID 18167382. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11.

- Cartsos VM, Zhu S, Zavras AI (January 2008). "Bisphosphonate use and the risk of adverse jaw outcomes: a medical claims study of 714,217 people". Journal of the American Dental Association. 139 (1): 23–30. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0016. PMID 18167381. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- Zadik Y, Abu-Tair J, Yarom N, Zaharia B, Elad S (September 2012). "The importance of a thorough medical and pharmacological history before dental implant placement". Australian Dental Journal. 57 (3): 388–92. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01717.x. PMID 22924366.

- Gaudin E, Seidel L, Bacevic M, Rompen E, Lambert F (October 2015). "Occurrence and risk indicators of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after dental extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 42 (10): 922–32. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12455. PMID 26362756.

- "Anti-resorptive Medical Definition". Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S (September 2008). "Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 83 (9): 1032–45. doi:10.4065/83.9.1032. PMC 2667901. PMID 18775204.

- Martin TJ (2000-06-01). "Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology: Bisphosphonates - mechanisms of action". Australian Prescriber. 23 (6): 130–132. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2000.144.

- Macluskey M, Sammut S (March 2017). Oral Health Management of Patients at Risk of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Dental Clinical Guidance. SDCEP. pp. 4, 5.

- Baron R, Ferrari S, Russell RG (April 2011). "Denosumab and bisphosphonates: different mechanisms of action and effects". Bone. 48 (4): 677–92. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.11.020. PMID 21145999.

- Durham S, Miller R, Davis C, Shepler BM (May 20, 2010). "Bisphosphonate Nephrotoxicity Risks and Use in CKD Patients". U.S. Pharmacist. 35 (5).

- Dahiya N, Khadka A, Sharma AK, Gupta AK, Singh N, Brashier DB (January 2015). "Denosumab: A bone antiresorptive drug". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 71 (1): 71–5. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.02.001. PMC 4297848. PMID 25609868.

- McClung MR (March 2017). "Denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis". Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia. 3 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.afos.2017.01.002. PMC 6372782. PMID 30775498.

- "Angiogenesis Inhibitors". National Cancer Institute. May 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

- Rosella D, Papi P, Giardino R, Cicalini E, Piccoli L, Pompa G (2016). "Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Clinical and practical guidelines". Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 6 (2): 97–104. doi:10.4103/2231-0762.178742. PMC 4820581. PMID 27114946.

- Al-Husein B, Abdalla M, Trepte M, Deremer DL, Somanath PR (December 2012). "Antiangiogenic therapy for cancer: an update". Pharmacotherapy. 32 (12): 1095–111. doi:10.1002/phar.1147. PMC 3555403. PMID 23208836.

- Hao Z, Sadek I (2016-09-08). "Sunitinib: the antiangiogenic effects and beyond". OncoTargets and Therapy. 9: 5495–505. doi:10.2147/OTT.S112242. PMC 5021055. PMID 27660467.

- Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ (June 2008). "Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy". Osteoporosis International. 19 (6): 733–59. doi:10.1007/s00198-007-0540-8. PMID 18214569. S2CID 24975272.

- Lindsay R, Cosman F. Osteoporosis. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York:McGraw-Hill, 2001:2226-37.

- Wood J, Bonjean K, Ruetz S, Bellahcène A, Devy L, Foidart JM, et al. (September 2002). "Novel antiangiogenic effects of the bisphosphonate compound zoledronic acid". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 302 (3): 1055–61. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.035295. PMID 12183663. S2CID 10313598.

- Vincenzi B, Santini D, Dicuonzo G, Battistoni F, Gavasci M, La Cesa A, et al. (March 2005). "Zoledronic acid-related angiogenesis modifications and survival in advanced breast cancer patients". Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 25 (3): 144–51. doi:10.1089/jir.2005.25.144. PMID 15767788.

- Santini D, Vincenzi B, Dicuonzo G, Avvisati G, Massacesi C, Battistoni F, et al. (August 2003). "Zoledronic acid induces significant and long-lasting modifications of circulating angiogenic factors in cancer patients". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (8): 2893–7. PMID 12912933.

- Chapurlat RD, Arlot M, Burt-Pichat B, Chavassieux P, Roux JP, Portero-Muzy N, Delmas PD (October 2007). "Microcrack frequency and bone remodeling in postmenopausal osteoporotic women on long-term bisphosphonates: a bone biopsy study". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 22 (10): 1502–9. doi:10.1359/jbmr.070609. PMID 17824840. S2CID 33483793.

- Stepan JJ, Burr DB, Pavo I, Sipos A, Michalska D, Li J, et al. (September 2007). "Low bone mineral density is associated with bone microdamage accumulation in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis". Bone. 41 (3): 378–85. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.198. PMID 17597017.

- Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR (May 2006). "Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws". Annals of Internal Medicine. 144 (10): 753–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.501.6469. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. PMID 16702591. S2CID 53091343.

- Medical News Today AAOMS Updates BRONJ Position Paper, January 23, 2009

- "Table 6. ONJ Staging System". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board, National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. 16 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Beth-Tasdogan, Natalie H.; Mayer, Benjamin; Hussein, Heba; Zolk, Oliver; Peter, Jens-Uwe (2022-07-12). "Interventions for managing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (7): CD012432. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012432.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 9309005. PMID 35866376.

- Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, Felsenberg D, McCauley LK, O'Ryan F, et al. (January 2015). "Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: a systematic review and international consensus". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 30 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2405. PMID 25414052.

- Svejda B, Muschitz C, Gruber R, Brandtner C, Svejda C, Gasser RW, et al. (February 2016). "[Position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ)]". Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 166 (1–2): 68–74. doi:10.1007/s10354-016-0437-2. PMID 26847441.

- Fliefel R, Tröltzsch M, Kühnisch J, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S (May 2015). "Treatment strategies and outcomes of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) with characterization of patients: a systematic review". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 44 (5): 568–85. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2015.01.026. PMID 25726090.

- Blus C, Szmukler-Moncler S, Giannelli G, Denotti G, Orrù G (23 August 2013). "Use of Ultrasonic Bone Surgery (Piezosurgery) to Surgically Treat Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws (BRONJ). A Case Series Report with at Least 1 Year of Follow-Up". The Open Dentistry Journal. 7 (1): 94–101. doi:10.2174/1874210601307010094. PMC 3772575. PMID 24044030.

- Management of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw, An Issue of Oral and Maxillofacial Clinics of North America 27-4. 7 Jan 2016. Salvatore L. Ruggiero

- Dodson TB (November 2015). "The Frequency of Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and its Associated Risk Factors". Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America. 27 (4): 509–16. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2015.06.003. PMID 26362367.