Denosumab

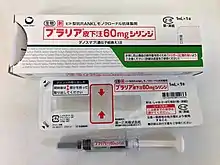

Denosumab (trade names Prolia and Xgeva) is a human monoclonal antibody for the treatment of osteoporosis, treatment-induced bone loss, metastases to bone, and giant cell tumor of bone.[1][2]

Denosumab injection | |

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Human |

| Target | RANK ligand |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Prolia, Xgeva |

| Other names | AMG-162 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a610023 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | N/A |

| Metabolism | proteolysis |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6404H9912N1724O2004S50 |

| Molar mass | 144722.80 g·mol−1 |

| | |

Denosumab is contraindicated in people with low blood calcium levels. The most common side effects are joint and muscle pain in the arms or legs.[3]

Denosumab is a inhibitor of RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand),[1] which works by preventing the development of osteoclasts, which are cells that break down bone. It was developed by the biotechnology company Amgen.[4]

Medical uses

Denosumab is used for those with osteoporosis at high risk for fractures, bone loss due to certain medications, and in those with bone metastases.[5]

Cancer

A 2012 meta-analysis found that denosumab was better than placebo, zoledronic acid and pamidronate, in reducing the risk of fractures in those with cancer.[6]

Adverse effects

The most common side effects are joint and muscle pain in the arms or legs.[3] There is an increased risk of infections such as cellulitis, hypocalcemia (low blood calcium), hypersensitivity allergy reactions, osteonecrosis of the jaw, and atypical femur fractures.[3][10] Another trial showed significantly increased rates of eczema and hospitalization due to infections of the skin.[11] It has been proposed that the increase in infections under denosumab treatment might be connected to the role of RANKL in the immune system.[12] RANKL is expressed by T helper cells, and is thought to be involved in dendritic cell maturation.[13]

Discontinuation of denosumab is associated with a rebound increase in bone turnover. In rare cases this has led to severe hypercalcemia, especially in children.[14] Vertebral compression fractures have also occurred in some people after discontinuing treatment.[14]

Contraindications and interactions

It is contraindicated in people with hypocalcemia; sufficient calcium and vitamin D levels must be reached before starting on denosumab therapy.[10] Data regarding interactions with other drugs are missing. It is unlikely that denosumab exhibits any clinically relevant interactions.[10]

Denosumab works by lowering the hormonal message that leads to excessive osteoclast-driven bone removal and is active in the body for only six months. Similarly to bisphosphonates, denosumab appears to be implicated in increasing the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) following extraction of teeth or oral surgical procedures but, unlike bisphosphonate, the risk declines to zero approximately 6 months after injection.[15] Invasive dental procedures should be avoided during this time.

Mechanism of action

Bone remodeling is the process by which the body continuously removes old bone tissue and replaces it with new bone. It is driven by various types of cells, most notably osteoblasts (which secrete new bone) and osteoclasts (which break down bone); osteocytes are also present in bone.

Precursors to osteoclasts, called pre-osteoclasts, express surface receptors called RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B). RANK is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily. RANK is activated by RANKL (the RANK-Ligand), which exists as cell surface molecules on osteoblasts. Activation of RANK by RANKL promotes the maturation of pre-osteoclasts into osteoclasts. Denosumab inhibits this maturation of osteoclasts by binding to and inhibiting RANKL. Denosumab mimics the natural action of osteoprotegerin, an endogenous RANKL inhibitor, that presents with decreasing concentrations (and perhaps decreased effectiveness) in patients with osteoporosis. This protects bone from degradation, and helps to counter the progression of the disease.[2]

Regulatory approval

United States

On 13 August 2009, a meeting was held between Amgen and the Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs (ACRHD) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to review the potential uses of denosumab.[16]

In October 2009, the FDA delayed approval of denosumab, stating that they needed more information.[17]

On 2 June 2010, denosumab was approved by the FDA for use in postmenopausal women with risk of osteoporosis[18] under the trade name Prolia,[19] and in November 2010 as Xgeva for the prevention of skeleton-related events in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors.[20] Denosumab is the first RANKL inhibitor to be approved by the FDA.[18]

On 13 June 2013, the FDA approved denosumab for treatment of adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumor of bone that is unresectable or where resection would result in significant morbidity.[21]

Europe

On 17 December 2009, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) issued a positive opinion for denosumab for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in women and for the treatment of bone loss in men with hormone ablation therapy for prostate cancer.[3] Denosumab was approved for marketing by the European Commission on 28 May 2010.

References

- Pageau SC (2009). "Denosumab". mAbs. 1 (3): 210–5. doi:10.4161/mabs.1.3.8592. PMC 2726593. PMID 20065634.

- McClung MR, Lewiecki EM, Cohen SB, Bolognese MA, Woodson GC, Moffett AH, et al. (February 2006). "Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (8): 821–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044459. PMID 16495394.

- "European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) for Prolia" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. October 16, 2014.

- "Prolia (denosumab)". Products. Amgen. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Denosumab". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Mar 16, 2015.

- Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, Henry DH, Brown JE, Yardley DA, et al. (November 2012). "Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials". European Journal of Cancer. 48 (16): 3082–92. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.002. PMID 22975218.

- Zhou Z, Chen C, Zhang J, Ji X, Liu L, Zhang G, et al. (2014). "Safety of denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low bone mineral density: a meta-analysis". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 7 (5): 2113–22. PMC 4069896. PMID 24966919.

- Josse R, Khan A, Ngui D, Shapiro M (March 2013). "Denosumab, a new pharmacotherapy option for postmenopausal osteoporosis". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 29 (3): 205–16. doi:10.1185/03007995.2013.763779. PMID 23297819. S2CID 206967103.

- Nayak S, Greenspan SL (March 2017). "Osteoporosis Treatment Efficacy for Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 65 (3): 490–495. doi:10.1111/jgs.14668. PMC 5358515. PMID 28304090.

- Haberfeld, H, ed. (2017). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Prolia-Injektionslösung in einer Fertigspritze. ISBN 978-3-85200-196-8.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, et al. (August 2009). "Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (8): 756–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.3489. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. PMID 19671655.

- Khosla S (August 2009). "Increasing options for the treatment of osteoporosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (8): 818–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMe0905480. PMC 3901579. PMID 19671654.

- EntrezGene 8600 TNFSF11 tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11; Homo sapiens

also known as RANKL. This protein was shown to be a dentritic cell survival factor and is involved in the regulation of T cell-dependent immune response.

- Boyce AM (August 2017). "Denosumab: an Emerging Therapy in Pediatric Bone Disorders". Current Osteoporosis Reports. 15 (4): 283–292. doi:10.1007/s11914-017-0380-1. PMC 5554707. PMID 28643220.

- "Injectable Prolia — Osteoporosis Update".

- "Amgen Issues Statement on Outcomes of Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs (ACRHD) Meeting". PRNewswire/FirstCall. August 13, 2009. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- Pollack A (19 October 2009). "F.D.A. Says No to an Amgen Bone Drug". The New York Times.

- "FDA Approves Denosumab for Osteoporosis". 2 June 2010.

- Matthew Perrone (June 2, 2010). "FDA clears Amgen's bone-strengthening drug Prolia". BioScience Technology. Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- "Amgen's Denosumab Cleared by FDA for Second Indication". 19 Nov 2010.

- "FDA Approval for Denosumab". Archived from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

Further reading

- Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Kostenuik PJ, Dougall WC, Sullivan JK, et al. (May 2012). "Bench to bedside: elucidation of the OPG-RANK-RANKL pathway and the development of denosumab". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 11 (5): 401–19. doi:10.1038/nrd3705. PMID 22543469. S2CID 7875371.

- Walker EP (February 7, 2012). "Benefit of Bone Drug in Prostate Cancer in Doubt". MedPage Today.

External links

- "Denosumab". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.