Osteonecrosis of the jaw

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a severe bone disease (osteonecrosis) that affects the jaws (the maxilla and the mandible). Various forms of ONJ have been described since 1861, and a number of causes have been suggested in the literature.

| Osteonecrosis of the jaws | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Osteonecrosis of the mandible |

| |

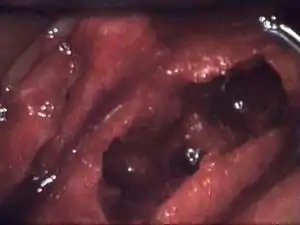

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw of the upper left jaw in a patient diagnosed with chronic venous insufficiency | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with bisphosphonate therapy, which is required by some cancer treatment regimens, has been identified and defined as a pathological entity (bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw) since 2003.[1] The possible risk from lower oral doses of bisphosphonates, taken by patients to prevent or treat osteoporosis, remains uncertain.[2]

Treatment options have been explored; however, severe cases of ONJ still require surgical removal of the affected bone.[3] A thorough history and assessment of pre-existing systemic problems and possible sites of dental infection are required to help prevent the condition, especially if bisphosphonate therapy is considered.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The definitive symptom of ONJ is the exposure of mandibular or maxillary bone through lesions in the gingiva that do not heal.[4] Pain, inflammation of the surrounding soft tissue, secondary infection or drainage may or may not be present. The development of lesions is most frequent after invasive dental procedures, such as extractions, and is also known to occur spontaneously. There may be no symptoms for weeks or months, until lesions with exposed bone appear.[5] Lesions are more common on the mandible than the maxilla.

- Pain and neuropathy[6]

- Erythema and suppuration

- Bad breath

Post radiation maxillary bone osteonecrosis is something that is found more in the lower jaw (mandible) rather than the maxilla (upper jaw) this is because there are many more blood vessels in the upper jaw.[7]

The symptoms of this are very similar to the symptoms of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). Patients are in a lot of pain, the area may swell up, bone may be seen and fractures may take place. The patients may also have a dry mouth and find it difficult to keep their mouth clean. A patient that has osteonecrosis may also be susceptible to bacterial and fungal infections.

The osteoblasts, which form the bone tissue are destroyed due to the radiation with increased activity of osteoclasts.

This condition cannot be treated by antibiotics as there is no blood supply to the bone, making it difficult for the antibiotics to reach the potential infection.

This condition makes eating and drinking very difficult, and surgical management removing the necrotic bone improves circulation and decreases microorganisms.

Causes

Toxic agents

Other factors such as toxicants can adversely impact bone cells. Infections, chronic or acute, can affect blood flow by inducing platelet activation and aggregation, contributing to a localized state of excess coagulability (hypercoagulability) that may contribute to clot formation (thrombosis), a known cause of bone infarct and ischaemia. Exogenous estrogens, also called hormonal disruptors, have been linked with an increased tendency to clot (thrombophilia) and impaired bone healing.[8]

Heavy metals such as lead and cadmium have been implicated in osteoporosis. Cadmium and lead promotes the synthesis of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) which is the major inhibitor of fibrinolysis (the mechanism by which the body breaks down clots) and shown to be a cause of hypofibrinolysis.[9] Persistent blood clots can lead to congestive blood flow (hyperemia) in bone marrow, impaired blood flow and ischaemia in bone tissue resulting in lack of oxygen (hypoxia), bone cell damage and eventual cell death (apoptosis). Of significance is the fact that the average concentration of cadmium in human bones in the 20th century has increased to about 10 times above the pre-industrial level.[10]

Bisphosphonates

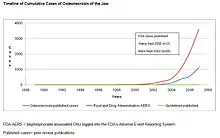

The first three reported cases of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw were spontaneously reported to the FDA by an oral surgeon in 2002, with the toxicity being described as a potentially late toxicity of chemotherapy.[11] In 2003 and 2004, three oral surgeons independently reported to the FDA information on 104 cancer patients with bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw seen in their referral practices in California, Florida, and New York.[12][13][14] These case series were published as peer-reviewed articles – two in the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and one in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Subsequently, numerous instances of persons with this adverse drug reaction were reported to the manufacturers and to the FDA. By December 2006, 3607 cases of people with this ADR had been reported to the FDA and 2227 cases had been reported to the manufacturer of intravenous bisphosphonates.

The International Myeloma Foundation's web-based survey included 1203 respondents, 904 patients with myeloma and 299 with breast cancer and an estimate that after 36 months, osteonecrosis of the jaw had been diagnosed in 10% of 211 patients on zoledronate and 4% of 413 on pamidronate.[15] A population based study in Germany identified more than 300 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw, 97% occurring in cancer patients (on high-dose intravenous bisphosphonates) and 3 cases in 780,000 patients with osteoporosis for an incidence of 0.00038%. Time to event ranged from 23 to 39 months and 42–46 months with high dose intravenous and oral bisphosphonates.[16] A prospective, population based study by Mavrokokki et al.. estimated an incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw of 1.15% for intravenous bisphosphonates and 0.04% for oral bisphosphonates. Most cases (73%) were precipitated by dental extractions. In contrast, safety studies sponsored by the manufacturer reported bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw rates that were much lower.

Although the majority of cases of ONJ have occurred in cancer patients receiving high dose intravenous bisphosphonates, almost 800 cases have been reported in oral bisphosphonate users for osteoporosis or Pagets disease. In terms of severity most cases of ONJ in oral bisphosphonate users are stage 1–2 and tend to progress to resolution with conservative measures such as oral chlorhexidine rinses.

Owing to prolonged embedding of bisphosphonate drugs in the bone tissues, the risk for BRONJ is high even after stopping the administration of the medication for several years.[17][18]

This form of therapy has been shown to prevent loss of bone mineral density (BMD) as a result of a reduction in bone turnover. However, bone health entails quite a bit more than just BMD. There are many other factors to consider.

In healthy bone tissue there is a homeostasis between bone resorption and ossification. Diseased or damaged bone is resorbed through the osteoclasts mediated process while osteoblasts form new bone to replace it, thus maintaining healthy bone density. This process is commonly called remodelling.

However, osteoporosis is essentially the result of a lack of new bone formation in combination with bone resorption in reactive hyperemia, related to various causes and contributing factors, and bisphosphonates do not address these factors at all.

In 2011, a proposal incorporating both the reduced bone turnover and the infectious elements of previous theories has been put forward. It cites the impaired functionality of affected macrophages as the dominant factor in the development of ONJ.[19]

In a systematic review of cases of bisphosphonate-associated ONJ up to 2006, it was concluded that the mandible is more commonly affected than the maxilla (2:1 ratio), and 60% of cases are preceded by a dental surgical procedure. According to Woo, Hellstein and Kalmar, oversuppression of bone turnover is probably the primary mechanism for the development of this form of ONJ, although there may be contributing co-morbid factors (as discussed elsewhere in this article). It is recommended that all sites of potential jaw infection should be eliminated before bisphosphonate therapy is initiated in these patients to reduce the necessity of subsequent dentoalveolar surgery. The degree of risk for osteonecrosis in patients taking oral bisphosphonates, such as alendronate (Fosamax), for osteoporosis is uncertain and warrants careful monitoring.[20] Patients taking dexamethasone and other glucocorticoids are at increased risk.[21]

Matrix metalloproteinase 2 may be a candidate gene for bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw, since it is the only gene known to be associated with bone abnormalities and atrial fibrillation, both of which are side effects of bisphosphonates.[22]

Pathophysiology

Histopathological alterations

Persons with ONJ may have either necrotic bone or bone marrow that has been slowly strangulated or nutrient-starved. Bone with chronically poor blood flow develops either a fibrous marrow since fibres can more easily live in nutrient starved areas, a greasy, dead fatty marrow (wet rot), a very dry, sometimes leathery marrow (dry rot), or a completely hollow marrow space (osteocavitation), also typical of ONJ. The blood flow impairment occurs following a bone infarct, a blood clot forming inside the smaller blood vessels of cancellous bone tissue.

Under ischaemic conditions numerous pathological changes in the bone marrow and trabeculae of oral cancellous bone have been documented. Microscopically, areas of "apparent fatty degeneration and/or necrosis, often with pooled fat from destroyed adipose cells (oil cysts) and with marrow fibrosis (reticular fatty degeneration)" are seen. These changes are present even if "most bony trabeculae appear at first glance viable, mature and otherwise normal, but closer inspection demonstrates focal loss of osteocytes and variable micro cracking (splitting along natural cleavage planes). The microscopic features are similar to those of ischaemic or aseptic osteonecrosis of long bones, corticosteroid-induced osteonecrosis, and the osteomyelitis of caisson (deep-sea diver's) disease".[23]

In the cancellous portion of femoral head it is not uncommon to find trabeculae with apparently intact osteocytes which seem to be "alive" but are no longer synthetizing collagen. This appears to be consistent with the findings in alveolar cancellous bone.[24]

Osteonecrosis can affect any bone, but the hips, knees and jaws are most often involved. Pain can often be severe, especially if teeth and/or a branch of the trigeminal nerve is involved, but many patients do not experience pain, at least in the earlier stages. When severe facial pain is purported to be caused by osteonecrosis, the term NICO, for neuralgia-inducing cavitational osteonecrosis, is sometimes used, but this is controversial and far from completely understood.[25]

ONJ, even in its mild or minor forms, creates a marrow environment that is conducive to bacterial growth. Since many individuals have low-grade infections of the teeth and gums, this probably is one of the major mechanisms by which the marrow blood flow problem can worsen; any local infection / inflammation will cause increased pressures and clotting in the area involved. No other bones have this mechanism as a major risk factor for osteonecrosis. A wide variety of bacteria have been cultured from ONJ lesions. Typically, they are the same microorganisms as those found in periodontitis or devitalized teeth. However, according to special staining of biopsied tissues, bacterial elements are rarely found in large numbers. So while ONJ is not primarily an infection, many cases have a secondary, very low-level of bacterial infection and chronic non-suppurative osteomyelitis can be associated with ONJ. Fungal infections in the involved bone do not seem to be a problem, but viral infections have not been studied. Some viruses, such as the smallpox virus (no longer existent in the wild) can produce osteonecrosis.

Effects of persistent ischaemia on bone cells

Cortical bone is well vascularized by the surrounding soft tissues thus less susceptible to ischaemic damage. Cancellous bone, with its mesh like structure and spaces filled with marrow tissue is more susceptible to damage by bone infarcts, leading to hypoxia and premature cell apoptosis.[14][15][26][27] The mean life-span of osteocytes has been estimated to be 15 years in cancellous bone,[28] and 25 years in cortical bone.[29] while the average lifespan of human osteoclasts is about 2 to 6 weeks and the average lifespan of osteoblasts is approximately 3 months.[30] In healthy bone these cells are constantly replaced by differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSC).[31] However, in both non-traumatic osteonecrosis and alcohol-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head, a decrease in the differentiation ability of mesenchymal stem into bone cells has been demonstrated,[32][33] and altered osteoblastic function plays a role in ON of the femoral head.[34] If these results are extrapolated to ONJ the altered differentiation potential of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) combined with the altered osteoblastic activity and premature death of existing bone cells would explain the failed attempts at repair seen in ischaemic-damaged cancellous bone tissue in ONJ.

The rapidity with which premature cell death can occur depends on the cell type and the degree and duration of the anoxia. Haematopoietic cells, in bone marrow, are sensitive to anoxia and are the first to die after reduction or removal of the blood supply. In anoxic conditions they usually die within 12 hours. Experimental evidence suggests that bone cells composed of osteocytes, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts die within 12–48 hours, and marrow fat cells die within 120 hours.[16] The death of bone does not alter its radiographic opacity nor its mineral density. Necrotic bone does not undergo resorption; therefore, it appears relatively more opaque.

Attempts at repair of ischaemic-damaged bone will usual occur in 2 phases. First, when dead bone abuts live marrow, capillaries and undifferentiated mesenchymal cells grow into the dead marrow spaces, while macrophages degrade dead cellular and fat debris. Second, mesenchymal cells differentiate into osteoblasts or fibroblasts. Under favorable conditions, layers of new bone form on the surface of dead spongy trabeculae. If sufficiently thickened, these layers may decrease the radiodensity of the bone; therefore, the first radiographic evidence of previous osteonecrosis may be patchy sclerosis resulting from repair. Under unfavorable conditions repeated attempts at repair in ischaemic conditions can be seen histologically and are characterized by extensive delamination or microcracking along cement lines as well as the formation of excessive cement lines.[35] Ultimate failure of repair mechanisms due to persistent and repeated ischaemic events is manifested as trabecular fractures that occur in the dead bone under functional load. Later followed by cracks and fissures leading to structural collapse of the area involved (osteocavitation).[16]

Diagnosis

Classification

| Grade | Size (diameter*) |

|---|---|

| 1A | Single lesion, <0.5 cm |

| 1B | Multiple lesions, largest <0.5 cm |

| 2A | Single lesion <1.0 cm |

| 2B | Multiple lesions, largest <1.0 cm |

| 3A | Single lesion, ≤2.0 cm |

| 3B | Multiple lesions, largest ≤2.0 cm |

| 4A | Single lesion >2.0 cm |

| 4B | Multiple lesions, largest >2.0 cm |

| *Lesion size measured as the largest diameter | |

| Grade | Severity |

|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic |

| 2 | Mild |

| 3 | Moderate |

| 4 | Severe |

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is classified based on severity, number of lesions, and lesion size. Osteonecrosis of greater severity is given a higher grade, with asymptomatic ONJ designated as grade 1 and severe ONJ as grade 4.

Treatment

The treatment should be tailored to the cause involved and the severity of the disease process. With oral osteoporosis the emphasis should be on good nutrient absorption and metabolic wastes elimination through a healthy gastro-intestinal function, effective hepatic metabolism of toxicants such as exogenous estrogens, endogenous acetaldehyde and heavy metals, a balanced diet, healthy lifestyle, assessment of factors related to potential coagulopathies, and treatment of periodontal diseases and other oral and dental infections.

In cases of advanced oral ischaemic osteoporosis and/or ONJ that are not bisphosphonates related, clinical evidence has shown that surgically removing the damaged marrow, usually by curettage and decortication, will eliminate the problem (and the pain) in 74% of patients with jaw involvement.[3] Repeat surgeries, usually smaller procedures than the first, may be required. Almost a third of jawbone patients will need surgery in one or more other parts of the jaws because the disease so frequently present multiple lesions, i.e., multiple sites in the same or similar bones, with normal marrow in between. In the hip, at least half of all patients will get the disease in the opposite hip over time; this pattern occurs in the jaws as well. Recently, it has been found that some osteonecrosis patients respond to anticoagulation therapies alone. The earlier the diagnosis the better the prognosis. Research is ongoing on other non-surgical therapeutic modalities that could alone or in combination with surgery further improve the prognosis and reduce the morbidity of ONJ. A greater emphasis on minimizing or correcting known causes is necessary while further research is conducted on chronic ischaemic bone diseases such as oral osteoporosis and ONJ.

In patients with bisphosphonates-associated ONJ, the response to surgical treatment is usually poor.[36] Conservative debridement of necrotic bone, pain control, infection management, use of antimicrobial oral rinses, and withdrawal of bisphosphonates are preferable to aggressive surgical measures for treating this form of ONJ.[37] Although an effective treatment for bisphosphonate-associated bone lesions has not yet been established,[38] and this is unlikely to occur until this form of ONJ is better understood, there have been clinical reports of some improvement after 6 months or more of complete cessation of bisphosphonate therapy.[39]

History

ONJ is not a new disease: around 1850, forms of "chemical osteomyelitis" resulting from environmental pollutants, such as lead and the white phosphorus used in early (non-safety) matches (Phossy jaw), as well as from popular medications containing mercury, arsenic or bismuth, were reported in the literature.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46] This disease apparently did not often occur in individuals with good gingival health, and usually targeted the mandible first.[41] It was associated with localized or generalized deep ache or pain, often of multiple jawbone sites. The teeth often appeared sound and suppuration was not present. Even so, the dentist often began extracting one tooth after another in the region of pain, often with temporary relief but usually to no real effect.[42]

Today a growing body of scientific evidence indicates that this disease process, in the cancellous bone and bone marrow, is caused by bone infarcts mediated by a range of local and systemic factors. Bone infarcts as well as damage to the deeper portion of the cancellous bone is an insidious process. It is certainly not visible clinically and routine imaging techniques such as radiographs are not effective for that sort of damage. "An important and often incompletely understood principle of radiography is the amount of bone destruction that goes undetected by routine x-rays procedures; this has been demonstrated by numerous investigators. Destruction confined to the cancellous portion of the bone cannot be detected radiographically, as radiolucencies appear only when there is internal or external erosion or destruction of the bone cortex."[47] In fact no radiographic findings are specific for bone infarction / osteonecrosis. A variety of pathologies may mimic bone infarction, including stress fractures, infections, inflammations, and metabolic and neoplastic processes. The limitations apply to all imaging modalities, including plain radiography, radionuclide studies, CT scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Through-transmission alveolar ultrasound, based on quantitative ultrasound (QUS) in combination with panoramic dental radiography (orthopantomography) is helpful in assessing changes in jawbone density.[48][49] When practitioners have an up-to-date understanding of the disease process and a good medical history is combined with detailed clinical findings, the diagnosis, with the help of various imaging modalities, can be achieved earlier in most patients.

In the modern dental profession, it is only recently, when severe cases associated with bisphosphonates came to light, that the issue of ONJ has been brought to the attention of a majority of dentists. At present, the focus is mostly on bisphosphonate-associated cases, and is sometimes referred to colloquially as "phossy jaw", a similar, earlier occupational disease.[50][51] However, the pharmaceutical manufacturers of bisphosphonates drugs such as Merck and Novartis have stated that ONJ in patients on this class of drug, can be related to a pre-existing condition, coagulopathy, anemia, infection, use of corticosteroids, alcoholism and other conditions already known to be associated with ONJ in the absence of bisphosphonate therapy. The implication is that bisphosphonates may not be the initiating cause of ONJ and that other pre-existing or concurrent systemic and/or local dental factors are involved.[52][53]

Since ONJ has been diagnosed in many patients who did not take bisphosphonates, it is thus logical to assume that bisphosphonates are not the only factor in ONJ. While the oversuppression of bone turnover seems to play a major role in aggravating the disease process, other factors can and do initiate the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for ONJ. In non-bisphosphonate cases of ONJ, it is mainly the cancellous portion of the bone and its marrow content that are involved in the disease process. The first stage is an oedema of the bone marrow initiated by a bone infarct, which is itself modulated by numerous causes, leading to myelofibrosis as a result of hypoxia and gradual loss of bone density characteristic of ischaemic osteoporosis. Further deterioration can be triggered by additional bone infarcts leading to anoxia and localized areas of osteonecrosis within the osteoporotic cancellous bone. Secondary events such as dental infection, injection of local anaesthetics with vasoconstrictors, such as epinephrine, and trauma can add further complications to the disease process and chronic non-pus forming bone infection osteomyelitis can also be associated with ONJ.[54][55][56]

However, in patients on bisphosphonates, the cortical bone is frequently involved as well. Spontaneous exposure of necrotic bone tissue through the oral soft tissues or following non-healing bone exposure after routine dental surgery, characteristics of this form of ONJ, may be the result of late diagnosis of a disease process that has been masked by the oversuppression of osteoclastic activity, allowing pre-existing factors to further aggravate bone damage.

References

- Alexandru Bucur, Tiberiu Niță, Octavian Dincă, Cristian Vlădan, Mihai Bogdan Bucur (November 2011). "Bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw". Rev. chir. oro-maxilo-fac. implantol. (in Romanian). 2 (3): 24–27. ISSN 2069-3850. 43. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)(webpage has a translation button) - Woo S; Hellstein J; Kalmar J (2006). "Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws". Ann Intern Med. 144 (10): 753–61. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. PMID 16702591. S2CID 53091343.

- Bouquot JE; Christian J (1995). "Long-term effects of jawbone curettage on the pain of facial neuralgia". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 53 (4): 387–97, discussion 397–9. doi:10.1016/0278-2391(95)90708-4. PMID 7699492.

- Journal of Bone and Minerl Research, 2007, Bisphosphonate-Associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw: Report of a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research

- American Dental Association, Osteonecrosis of the Jaw Archived 3 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Zadik Y, Benoliel R, Fleissig Y, Casap N (February 2012). "Painful trigeminal neuropathy induced by oral bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a new etiology for the numb-chin syndrome". Quintessence Int. 43 (2): 97–104. PMID 22257870.

- Auto fluorescence image of post-radiation maxillary bone osteonecrosis in a 64-year-old patient – Case Report Aleksandra Szczepkowska1, Paweł Milner1, Anna Janas 1 Institute of Dental Surgery, Medical University, Łódź, Poland

- Glueck C; McMahon R; Bouquot J; Triplett D (1998). "Exogenous estrogen may exacerbate thrombophilia, impair bone healing and contribute to development of chronic facial pain". Cranio. 16 (3): 143–53. doi:10.1080/08869634.1998.11746052. PMID 9852807.

- Yamamoto C (May 2000). "[Toxicity of cadmium and lead on vascular cells that regulate fibrinolysis]". Yakugaku Zasshi. 120 (5): 463–73. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.120.5_463. PMID 10825810.

- Jaworowski Z; Barbalat F; Blain C; Peyre E (1985). "Heavy metals in human and animal bones from ancient and contemporary France". Sci. Total Environ. 43 (1–2): 103–26. Bibcode:1985ScTEn..43..103J. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(85)90034-8. PMID 4012292.

- Lewis RJ; Johnson RD; Angier MK; Vu NT (2004). "Ethanol formation in unadulterated postmortem tissues". Forensic Sci. Int. 146 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.03.015. PMID 15485717.

- Yajima D; Motani H; Kamei K; Sato Y; Hayakawa M; Iwase H (2006). "Ethanol production by Candida albicans in postmortem human blood samples: effects of blood glucose level and dilution". Forensic Sci. Int. 164 (2–3): 116–21. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.009. PMID 16427751.

- Cordts PR; Kaminski MV; Raju S; Clark MR; Woo KM (2001). "Could gut-liver function derangements cause chronic venous insufficiency?". Vasc Surg. 35 (2): 107–14. doi:10.1177/153857440103500204. PMID 11668378. S2CID 24476409.

- Marcus R; Feldman D; Kelsey J (1996). Osteoporosis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. Vol. 81. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550734. ISBN 978-0-12-470863-1. PMID 8550734.

- Bullough PG (1997). Orthopaedic pathology (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Wolfe-Mosby.

- Bone infarct at eMedicine

- Zadik Y, Abu-Tair J, Yarom N, Zaharia B, Elad S (September 2012). "The importance of a thorough medical and pharmacological history before dental implant placement". Australian Dental Journal. 57 (3): 388–392. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01717.x. PMID 22924366.

- Rodan GA; Reszka AA (2003). "Osteoporosis and bisphosphonates". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 85-A (Suppl 3): 8–12. doi:10.2106/00004623-200300003-00003. PMID 12925603.

- Pazianas M (February 2011). "Osteonecrosis of the jaw and the role of macrophages". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103 (3): 232–40. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq516. PMID 21189409.

- Woo SB; Hellstein JW; Kalmar JR (2006). "Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws". Ann. Intern. Med. 144 (10): 753–61. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. PMID 16702591. S2CID 53091343.

- Marx RE; Sawatari Y; Fortin M; Broumand V (November 2005). "Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 63 (11): 1567–75. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. PMID 16243172.

- Lehrer S; Montazem A; Ramanathan L; et al. (January 2009). "Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws, bone markers, and a hypothesized candidate gene". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 67 (1): 159–61. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.015. PMID 19070762.

- Neville BW; Damn D; Allen C; Bouquot JE (1995). "Facial pain and neuromuscular diseases.". Oral and maxillofacial pathology. Head and Neck Pathology. Vol. 1. W.B Saunders Co. pp. 631–632. doi:10.1007/s12105-007-0007-4. PMC 2807501. PMID 20614286.

- Arlet J; Durroux R; Fauchier C; Thiechart M. "Topographic and evolutive aspects". In Arlet J; Ficat PR; Hungerford DS. (eds.). Histophatology of the nontraumatic necrosis of the femoral head.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CA, Bouquot JE (2002). Oral & maxillofacial pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 746. ISBN 978-0721690032.

- Kanus JA. (1996). Textbook of osteoporosis. Osford: Blackwell Science Ltd.

- Vigorita VJ. (1999). Orthopaedic pathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Parfitt AM (1994). "Osteonal and hemi-osteonal remodeling: the spatial and temporal framework for signal traffic in adult human bone". J. Cell. Biochem. 55 (3): 273–86. doi:10.1002/jcb.240550303. PMID 7962158. S2CID 25933384.

- Parfin AM; Kleerekoper M; Villanueva AR (1987). "Increased bone age: mechanisms and consequences". Osteoporosis. Copenhagen: Osteopress. pp. 301–308.

- Frost HM (1963). Bone Remodeling Dynamics. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Owen M; Friedenstein AJ (1988). "Stromal stem cells: marrow- derived osteogenic precursors". Ciba Found Symp. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 136: 42–60. doi:10.1002/9780470513637.ch4. ISBN 9780470513637. PMID 3068016.

- Lee JS; Lee JS; Roh HL; Kim CH; Jung JS; Suh KT (2006). "Alterations in the differentiation ability of mesenchymal stem cells in patients with nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: comparative analysis according to the risk factor". J. Orthop. Res. 24 (4): 604–9. doi:10.1002/jor.20078. PMID 16514658.

- Suh KT; Kim SW; Roh HL; Youn MS; Jung JS (2005). "Decreased osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in alcohol-induced osteonecrosis". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 431 (431): 220–5. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000150568.16133.3c. PMID 15685079. S2CID 24313981.

- Gangji V; Hauzeur JP; Schoutens A; Hinsenkamp M; Appelboom T; Egrise D (2003). "Abnormalities in the replicative capacity of osteoblastic cells in the proximal femur of patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head". J. Rheumatol. 30 (2): 348–51. PMID 12563694.

- Adams WR; Spolnik KJ; Bouquot JE (1999). "Maxillofacial osteonecrosis in a patient with multiple "idiopathic" facial pains". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 28 (9): 423–32. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02101.x. PMID 10535367.

- Zarychanski R; Elphee E; Walton P; Johnston J (2006). "Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with pamidronate therapy". Am. J. Hematol. 81 (1): 73–5. doi:10.1002/ajh.20481. PMID 16369966. S2CID 11830192.

- Abu-Id MH; Açil Y; Gottschalk J; Kreusch T (2006). "[Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw]". Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir (in German). 10 (2): 73–81. doi:10.1007/s10006-005-0670-0. PMID 16456688. S2CID 43852043.

- Merigo E; Manfredi M; Meleti M; Corradi D; Vescovi P (2005). "Jaw bone necrosis without previous dental extractions associated with the use of bisphosphonates (pamidronate and zoledronate): a four-case report". Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 34 (10): 613–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00351.x. PMID 16202082.

- Gibbs SD; O'Grady J; Seymour JF; Prince HM (2005). "Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw requires early detection and intervention". Med. J. Aust. 183 (10): 549–50. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07172.x. PMID 16296983. S2CID 27182893.

- Bond TE Jr. (1848). A practical treatise on dental medicine. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston.

- "Necrosis of the lower jaw in makers of Lucifer matches". Am J Dent Science. 1 (series 3): 96–7. 1867.

- "The History of Maxillofacial Osteonecrosis (NICO)" Archived 16 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Bouquot J.E.

- Ferguson W (1868). "New treatment of necrosis". Am J Dent Science. 1 (series 3): 189.

- Noel HR (1868). "A lecture on caries and necrosis of bone". Am J Dent Science. 1 (series 3): 425, 482.

- Barrett WC (1898). Oral pathology and practice. Philadelphia: S.S. White Dental Mfg Co.

- Black GV (1915). A work on special dental pathology (2nd ed.). Chicago: Medico_Dental Publ Co.

- Burns RC; Cohen S (1980). Pathways of the pulp (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby. pp. 55–7. ISBN 978-0-8016-1009-7.

- Imbeau J (2005). "Introduction to through-transmission alveolar ultrasonography (TAU) in dental medicine". Cranio. 23 (2): 100–12. doi:10.1179/crn.2005.015. PMID 15898566. S2CID 19092618.

- Bouquot J; Margolis M; Shankland WE; Imbeau J (April 2002). "Through-transmission alveolar sonography (TTAS) – a new technology for evaluation of medullary diseases, correlation with histopathology of 285 scanned jaw sites". 56th annual meeting of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology.

- Purcell PM; Boyd IW (2005). "Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw". Med. J. Aust. 182 (8): 417–8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06762.x. PMID 15850440. S2CID 45055845.

- Carreyrou J (12 April 2006). "Fosamax Drug Could Become Next Merck Woe". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones.

- "Statement by Merck regarding Fosamax and rare cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw". Merck.

- "Osteonecrosis of the Jaw". Novartis.

- Bouquot J; Wrobleski G; Fenton S (2000). "The most common osteonecrosis? Prevalence of maxillofacial osteonecrosis (MFO)". J Oral Pathol Med. 29: 345.

- Glueck CJ; McMahon RE; Bouquot J; et al. (1996). "Thrombophilia, hypofibrinolysis, and alveolar osteonecrosis of the jaws". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 81 (5): 557–66. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80047-3. PMID 8734702.

- Gruppo R; Glueck C; McMahon R; Bouquot J; Rabinovich B; Becker A; Tracy T; Wang P (1996). "The pathophysiology of alveolar osteonecrosis of the jaw: anticardiolipin antibodies, thrombophilia, and hypofibrinolysis". J Lab Clin Med. 127 (5): 481–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-2143(96)90065-7. PMID 8621985.