Abfraction

Abfraction is a theoretical concept explaining a loss of tooth structure not caused by tooth decay (non-carious cervical lesions). It is suggested that these lesions are caused by forces placed on the teeth during biting, eating, chewing and grinding; the enamel, especially at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), undergoes large amounts of stress, causing micro fractures and tooth tissue loss. Abfraction appears to be a modern condition, with examples of non-carious cervical lesions in the archaeological record typically caused by other factors.[1]

Definition

Abfraction is a form of non-carious tooth tissue loss that occurs along the gingival margin.[2] In other words, abfraction is a mechanical loss of tooth structure that is not caused by tooth decay, located along the gum line. There is theoretical evidence to support the concept of abfraction, but little experimental evidence exists.[3]

The term abfraction was first published in 1991 in a journal article dedicated to distinguishing the lesion. The article was titled "Abfractions: A New Classification of Hard Tissue Lesions of Teeth" by John O. Grippo.[4] This article introduced the definition of abfraction as a "pathologic loss of hard tissue tooth substance caused by bio mechanical loading forces". This article was the first to establish abfraction as a new form of lesion, differing from abrasion, attrition, and erosion.[2]

Tooth tissue is gradually weakened causing tissue loss through fracture and chipping or successively worn away leaving a non-carious lesion on the tooth surface. These lesions occur in both the dentine and enamel of the tooth. These lesions generally occur around the cervical areas of the dentition.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Abfraction lesions will generally occur in the region on the tooth where the greatest tensile stress is located. In statements such as these there is no comment on whether the lesions occur above or below the CEJ. One theory suggests that the abfraction lesions will only form above the CEJ.[6][7][8][9] However, it is assumed that the abfraction lesions will occur anywhere in the cervical areas of affected teeth. It is important to note that studies supporting this configuration of abfraction lesions also state that when there is more than one abnormally large tensile stress on a tooth two or more abfraction lesions can result on the one surface.[3]

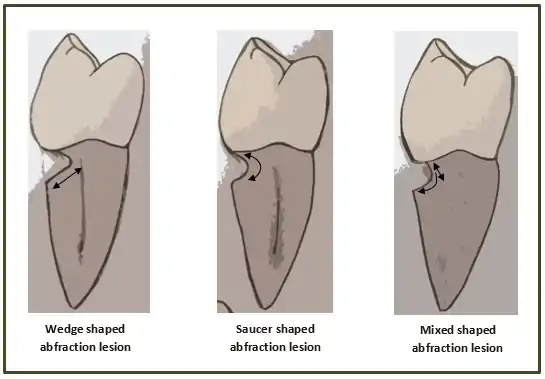

When looking at abfraction lesions there are generally three shapes in which they appear, appearing as either wedge, saucer or mixed patterns.[6] Wedge and saucer shaped lesions are the most common, whereas mixed lesions are less frequently identified in the oral cavity.[6] In reference to figure 1, wedge shaped lesions have the sharpest internal line angles and saucer/mixed shaped lesions are either smooth internally, or a variety.

Clinically, people with abfraction lesions can also present with tooth sensitivity in the associated areas. This occurs because as the abfraction lesions appear, dentine/cementum is exposed.[10] The dentine and cementum are less dense than tooth enamel and therefore more susceptible to sensation from thermal/mechanical sources.[10]

Causes

As abfraction is still a controversial theory there are various ideas on what causes the lesions. Because of this controversy the true causes of abfraction also remain disputable.[11] Researchers have proposed that abfraction is caused by forces on the tooth from the teeth touching together, occlusal forces, when chewing and swallowing.[4][12] These lead to a concentration of stress and flexion at the area where the enamel and cementum meet (CEJ).[3][5] This theoretical stress concentration[13] and flexion over time causes the bonds in the enamel of the tooth to break down and either fracture or be worn away from other stressors such as erosion or abrasion.[3][5][11][12] The people who initially proposed the theory of abfraction believe the occlusal forces alone cause the lesions[13] without requiring the added abrasive components such as toothbrush and paste or erosion.[13]

If teeth come together in a non-ideal bite the researchers state that this would create further stress in areas on the teeth.[12] Teeth that come together too soon or come under more load than they are designed for could lead to abfraction lesions.[12] The impacts of restorations on the chewing surfaces of the teeth being the incorrect height has also been raised as another factor adding to the stress at the CEJ.[11]

Further research has shown that the normal occlusal forces from chewing and swallowing are not sufficient to cause the stress and flexion required to cause abfraction lesions.[3] However, these studies have shown that the forces are sufficient in a person who grinds their teeth (bruxism).[3] Several studies have suggested that it is more common among those who grind their teeth,[11][13] as the forces are greater and of longer duration. Yet further studies have shown that these lesions do not always appear in people with bruxism and others without bruxism have these lesions.[5]

There are other researchers who would state that occlusal forces have nothing to do with the lesions along the CEJ and that it is the result of abrasion from toothbrush with toothpaste that causes these lesions.[3][5][11]

Being theoretical in nature there is more than one idea on how abfraction presents clinically in the mouth. One theory of its clinical features suggests that the lesions only form above the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) (which is where the enamel and cementum meet on a tooth).[6][7][8][9] If this is kept in mind, it serves as a platform for it to be distinguished from other non-carious lesions, such as tooth-brush abrasion.

Treatment

Treatment of abfraction lesions can be difficult due to the many possible causes. To provide the best treatment option the dental clinician must determine the level of activity and predict possible progression of the lesion.[3][13] A No.12 scalpel is carefully used by the dental clinician to make a small indentation on the lesion, this is then closely monitored for changes. Loss of a scratch mark signifies that the lesion is active and progressing.

It is usually recommended when an abfraction lesion is less than 1 millimeter, monitoring at regular intervals is a sufficient treatment option. If there are concerns around aesthetics or clinical consequences such as dentinal hypersensitivity, a dental restoration (white filling) may be a suitable treatment option.

Aside from restoring the lesion, it is equally important to remove any other possible causative factors.[2] Adjustments to the biting surfaces of the teeth alter the way the upper and lower teeth come together, this may assist by redirecting the occlusal load.[2] The aim of this is to redirect the force of the load to the long axis of the tooth, therefore removing the stress on the lesion. This can also be achieved by altering the tooth surfaces such as cuspal inclines, reducing heavy contacts and removing premature contacts.[2] If bruxism is deemed a contributing factor an occlusal splint can be an effective treatment for eliminating the irregular forces placed on the tooth.[3][13]

Controversy

Abfraction has been a controversial subject since its creation in 1991.[11] This is due to the clinical presentation of the tooth loss, which often presents in a manner similar to that of abrasion or erosion. The major reasoning behind the controversy is the similarity of abfraction to other non carious lesions and the prevalence of multiple theories to potentially explain the lesion. One of the most prevalent theories is called "the theory of non-carious cervical lesions" which suggests that tooth flexion, occurring due to occlusion factors, impacts on the vulnerable area near the cementoenamel junction.[11] This theory is not widely accepted among the professional community as it suggests that the only factor is occlusion. Many researchers argue that this is inaccurate as they contend that the abfraction lesion is a multifactorial (has many causative factors) lesion with other factors such as abrasion or erosion.[5] This controversy around the causative factors, along with the recency of the lesion classification, are some of the reasons why many dental clinicians are looking at the lesion with some scepticism. More research is needed to fully clear up the controversy surrounding the abfraction lesion.

See also

References

- "Root grooves on two adjacent anterior teeth of Australopithecus africanus". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- Bartlett, D.W.; Shah, P (April 2006). "A Critical Review of Non-carious Cervical (Wear) Lesions and the Role of Abfraction, Erosion, and Abrasion". Journal of Dental Research. 85 (4): 306–312. doi:10.1177/154405910608500405. PMID 16567549. S2CID 41159919.

- Michael, JA; Townsend, GC; Greenwood, LF; Kaidonis, JA (March 2009). "Abfraction: separating fact from fiction". Australian Dental Journal. 54 (1): 2–8. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.01080.x. PMID 19228125.

- Grippo, John O (January–February 1991). "Abfractions: A New Classification of Hard Tissue Lesions of Teeth". Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 3 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8240.1991.tb00799.x. PMID 1873064.

- Sarode, Gargi S; Sarode, Sachin C (May 2013). "Abfraction: A review". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 17 (2): 222–227. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.119788. PMC 3830231. PMID 24250083.

- Hur, B; Kim, HC; Park, JK; Versluis, A (2011). "Characteristics of non-carious cervical lesions – an ex vivo study using micro computed tomography". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 38 (6): 469–74. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02172.x. PMID 20955394.

- Lee, HE; Lin, CL; Wang, CH; Cheng, CH; Chang, CH (2002). "Stresses at the cervical lesion of maxillary premolar—a finite element investigation". Journal of Dentistry. 30 (7): 283–90. doi:10.1016/s0300-5712(02)00020-9. PMID 12554108.

- Dejak, B; Młotkowski, A; Romanowicz, M (2003). "Finite element analysis of stresses in molars during clenching and mastication". Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 90 (6): 591–7. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2003.08.009. PMID 14668761.

- Borcic, J; Anic, I; Smojver, I; Catic, A; Miletic, I; Ribaric, SP (2005). "3D finite element model and cervical lesion formation in normal occlusion and in malocclusion". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 32 (7): 504–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01455.x. PMID 15975130.

- Bamise, Cornelius T.; Olusile, Adeyemi O.; Oginni, Adeleke O. (2008). "An Analysis of the Etiological and Predisposing Factors Related to Dentin Hypersensitivity". The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice. 9 (5): 9.

- Antonelli JR, Hottel TL, Garcia-Godoy F. Abfraction Lesions – Where do They Come From? A Review of the Literature. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2013; 93(1):14-19

- Grippo, JO; Simring, M; Coleman, TA (2012). "Abfraction, Abrasion, Biocorrosion, and the Enigma of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: A 20-Year Perspective". Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 24 (1): 10–23. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8240.2011.00487.x. PMID 22296690.

- Shetty, SM; Shetty, RG; Mattigatti, S; Managoli, NA; Rairam, SG; Patil, AM (2013). "No Carious Cervical Lesions". J Int Oral Health. 5 (5): 142–145.

- Summit, James B., J. William Robbins, and Richard S. Schwartz. Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A Contemporary Approach. 2nd edition. Carol Stream, Illinois, Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc, 2001. ISBN 0-86715-382-2.

- Lee, WC.; Eakle, WS. (1984). "Possible role of tensile stress in the etiology of cervical erosive lesions of teeth". Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 52 (3): 374–380. doi:10.1016/0022-3913(84)90448-7. PMID 6592336.