Meniscus (anatomy)

A meniscus is a crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous anatomical structure that, in contrast to an articular disc, only partly divides a joint cavity.[1] In humans they are present in the knee, wrist, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, and temporomandibular joints;[2] in other animals they may be present in other joints.

| Meniscus | |

|---|---|

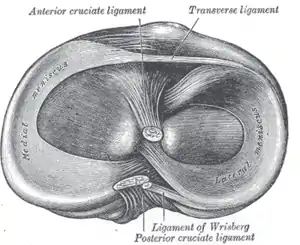

Head of right tibia seen from above, showing menisci and attachments of ligaments | |

Left knee-joint from behind, showing interior ligaments | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Menisci |

| Greek | μηνίσκος ("meniskos") |

| MeSH | D000072600 |

| TA98 | A03.0.00.033 |

| TA2 | 1544 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Generally, the term "meniscus" is used to refer to the cartilage of the knee, either to the lateral or medial meniscus. Both are cartilaginous tissues that provide structural integrity to the knee when it undergoes tension and torsion. The menisci are also known as "semi-lunar" cartilages, referring to their half-moon, crescent shape.

The term "meniscus" is from the Ancient Greek word μηνίσκος (meniskos), meaning "crescent".[3]

Structure

The menisci of the knee are two pads of fibrocartilaginous tissue which serve to disperse friction in the knee joint between the lower leg (tibia) and the thigh (femur). They are concave on the top and flat on the bottom, articulating with the tibia. They are attached to the small depressions (fossae) between the condyles of the tibia (intercondyloid fossa), and towards the center they are unattached and their shape narrows to a thin shelf.[4] The blood flow of the meniscus is from the periphery (outside) to the central meniscus. Blood flow decreases with age and the central meniscus is avascular by adulthood, which slows healing.

Menisci shows low-intensity on MRI images.[5]

Function

The menisci act to disperse the weight of the body and reduce friction during movement. Since the condyles of the femur and tibia meet at one point (which changes during flexion and extension), the menisci spread the load of the body's weight.[6] This differs from sesamoid bones, which are made of osseous tissue and whose function primarily is to protect the nearby tendon and to increase its mechanical effect.

Clinical significance

Injury

In sports and orthopedics, people sometimes speak of "torn cartilage" and will actually be referring to an injury to one of the menisci. There are two general types of meniscus injuries: acute tears that are often the result of trauma or a sports injury and chronic or wear-and-tear type tears. Acute tears have many different shapes (vertical, horizontal, radial, oblique, complex) and sizes. They are often treated with surgical repair depending upon the patient's age as they rarely heal on their own. Chronic tears are treated symptomatically: physical therapy with or without the addition of injections and anti-inflammatory medications. If the tear causes continued pain, swelling, or knee dysfunction, then the tear can be removed or repaired surgically. The unhappy triad is a set of commonly co-occurring knee injuries which includes injury to the medial meniscus.

Conservative management

Conservative management is often considered first for a smaller or chronic tear that does not appear to require surgical repair. It consists of activity modification or physical therapy to strengthen and increase the range of motion.

Surgical treatment

Two surgeries of the meniscus are most common. Depending on the type and location of the tear, the patient's age, and physician's preference, injured menisci are usually either repaired or removed, in part or completely (meniscectomy). Each has its advantages and disadvantages. Many studies show the meniscus serves a purpose and therefore doctors will attempt to repair when possible. However, the meniscus has poor blood supply, and, therefore, healing can be difficult. Traditionally it was thought that if there is no chance of healing, then it is best to remove the damaged and non-functional meniscus, although at least one study has shown that there is little significance if a meniscectomy is done.[7] However, resuming high intensity activities may be impossible without surgery as the tear may flap around, causing the knee to lock.

A 2017 clinical practice guideline strongly recommends against surgery in nearly all patients with degenerative knee disease.[8]

Etymology

The term meniscus derives from Greek μηνίσκος meniskos, meaning "crescent". The word was used for curved things in general, such as a necklace or a line of battle.[3]

Additional images

See also

References

- Platzer (2004), p 208

- "Meniscus", Stedman's (27th ed.)

- Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology, p. 199

- Gray's (1918), 7b

- Nguyen, Jie C.; De Smet, Arthur A.; Graf, Ben K.; Rosas, Humberto G. (July 2014). "MR Imaging–based Diagnosis and Classification of Meniscal Tears". RadioGraphics. 34 (4): 981–999. doi:10.1148/rg.344125202. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 25019436.

- Cluett, Meniscus Tear — Torn Cartilage

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, Kalske J, Järvinen TL (December 26, 2013). "Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy versus Sham Surgery for a Degenerative Meniscal Tear". The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (26): 2504–2514. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1305189. PMID 24369076.

- Siemieniuk, Reed A. C.; Harris, Ian A.; Agoritsas, Thomas; Poolman, Rudolf W.; Brignardello-Petersen, Romina; Velde, Stijn Van de; Buchbinder, Rachelle; Englund, Martin; Lytvyn, Lyubov (2017-05-10). "Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline". British Medical Journal. 357: j1982. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1982. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC 5426368. PMID 28490431.

- Sources

- "Meniscus". Stedman's Medical Dictionary, 27th edition. eMedicine - Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Cluett, Jonathan (February 10, 2008). "Meniscus Tear — Torn Cartilage". About.com. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Diab, Mohammad (1999). Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 90-5702-597-3.

- Gray, Henry (1918). "7b. The Knee-joint". Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.