Meridian (Chinese medicine)

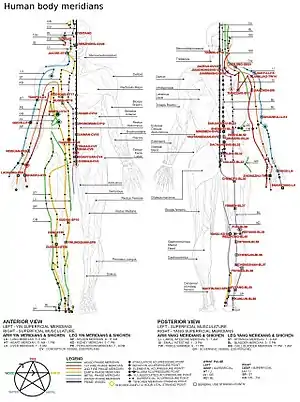

The meridian system (simplified Chinese: 经络; traditional Chinese: 經絡; pinyin: jīngluò, also called channel network) is a concept in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Meridians are paths through which the life-energy known as "qi" (ch'i) flows.[1]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Meridians are not real anatomical structures: scientists have found no evidence that supports their existence.[2] One historian of medicine in China says that the term is "completely unsuitable and misguided, but nonetheless it has become a standard translation."[3] Major proponents of their existence have not come to any consensus as to how they might work or be tested in a scientific context.

History

The concept of meridians are first attested in two works recovered from the Mawangdui and Zhangjiashan tombs of the Han-era Changsha Kingdom, the Cauterization Canon of the Eleven Foot and Arm Channels (足臂十一脈灸經, Zúbì Shíyī Mài Jiǔjīng) and the Cauterization Canon of the Eleven Yin and Yang Channels (陰陽十一脈灸經, Yīnyáng Shíyī Mài Jiǔjīng). In the texts, the meridians are referenced as mài (脈) rather than jīngmài.

Main concepts

The meridian network is typically divided into two categories, the jingmai (經脈) or meridian channels and the luomai (絡脈) or associated vessels (sometimes called "collaterals"). The jingmai contain the 12 tendinomuscular meridians, the 12 divergent meridians, the 12 principal meridians, the eight extraordinary vessels as well as the Huato channel, a set of bilateral points on the lower back whose discovery is attributed to the ancient physician Hua Tuo. The collaterals contain 15 major arteries that connect the 12 principal meridians in various ways, in addition to the interaction with their associated internal organs and other related internal structures. The collateral system also incorporates a branching expanse of capillary-like vessels which spread throughout the body, namely in the 12 cutaneous regions as well as emanating from each point on the principal meridians. If one counts the number of unique points on each meridian, the total comes to 361, which matches the number of days in a year, in the moon calendar system. Note that this method ignores the fact that the bulk of acupoints are bilateral, making the actual total 670.

There are about 400 acupuncture points (not counting bilateral points twice) most of which are situated along the major 20 pathways (i.e. 12 primary and eight extraordinary channels). However, by the second Century AD, 649 acupuncture points were recognized in China (reckoned by counting bilateral points twice).[4][5] There are "12 Principal Meridians" where each meridian corresponds to either a hollow or solid organ; interacting with it and extending along a particular extremity (i.e. arm or leg). There are also "Eight Extraordinary Channels", two of which have their own sets of points, and the remaining ones connecting points on other channels.

12 standard meridians

The 12 standard meridians, also called Principal Meridians, are divided into Yin and Yang groups. The Yin meridians of the arm are the Lung, Heart, and Pericardium. The Yang meridians of the arm are the Large Intestine, Small Intestine, and Triple Burner. The Yin Meridians of the leg are the Spleen, Kidney, and Liver. The Yang meridians of the leg are Stomach, Bladder, and Gall Bladder.[6]

The table below gives a more systematic list of the 12 standard meridians:[7]

| Meridian name (Chinese) | Quality of Yin or Yang | Extremity | Five Elements | Organ | Time of Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiyin Lung Channel of Hand (手太阴肺经) or Hand's Major Yin Lung Meridian | Greater Yin (taiyin, 太阴) | Hand (手) | Metal (金) | Lung (肺) | 寅; yín; 3 a.m. to 5 a.m. |

| Shaoyin Heart Channel of Hand (手少阴心经) or Hand's Minor Yin Heart Meridian | Lesser Yin (shaoyin, 少阴) | Hand (手) | Fire (火) | Heart (心) | 午; wǔ; 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. |

| Jueyin Pericardium Channel of Hand (手厥阴心包经) or Hand's Absolute Yin Heart Protector Meridian | Faint Yin (jueyin – 厥阴) | Hand (手) | Fire (火) | Pericardium (心包) | 戌; xū; 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. |

| Shaoyang Sanjiao Channel of Hand (手少阳三焦经) or Hand's Minor Yang Triple Burner Meridian | Lesser Yang (shaoyang, 少阳) | Hand (手) | Fire (火) | Triple Burner (三焦) | 亥; hài; 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. |

| Taiyang Small Intestine Channel of Hand (手太阳小肠经) or Hand's Major Yang Small Intestine Meridian | Greater Yang (taiyang, 太阳) | Hand (手) | Fire (火) | Small Intestine (小肠) | 未; wèi; 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. |

| Yangming Large Intestine Channel of Hand (手阳明大肠经) or Hand's Yang Supreme Large Intestine Meridian | Yang Bright (yangming, 阳明) | Hand (手) | Metal (金) | Large Intestine (大腸) | 卯; mǎo; 5 a.m. to 7 a.m. |

| Taiyin Spleen Channel of Foot (足太阴脾经) or Foot's Major Yin Spleen Meridian | Greater Yin (taiyin, 太阴) | Foot (足) | Earth (土) | Spleen (脾) | 巳; sì; 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. |

| Shaoyin Kidney Channel of Foot (足少阴肾经) or Foot's Minor Yin Kidney Meridian | Lesser Yin (shaoyin, 少阴) | Foot (足) | Water (水) | Kidney (腎) | 酉; yǒu; 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. |

| Jueyin Liver Channel of Foot (足厥阴肝经) or Foot's Absolute Yin Liver Meridian | Faint Yin (jueyin, 厥阴) | Foot (足) | Wood (木) | Liver (肝) | 丑; chǒu; 1 a.m. to 3 a.m. |

| Shaoyang Gallbladder Channel of Foot (足少阳胆经) or Foot's Minor Yang Gallbladder Meridian | Lesser Yang (shaoyang, 少阳) | Foot (足) | Wood (木) | Gall Bladder (膽) | 子; zǐ; 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. |

| Taiyang Bladder Channel of Foot (足太阳膀胱经) or Foot's Major Yang Urinary Bladder Meridian | Greater Yang (taiyang, 太阳) | Foot (足) | Water (水) | Urinary bladder (膀胱) | 申; shēn; 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. |

| Yangming Stomach Channel of Foot (足阳明胃经) or Foot's Yang Supreme Stomach Meridian | Yang Bright (yangming, 阳明) | Foot (足) | Earth (土) | Stomach (胃) | 辰; chén; 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. |

Eight extraordinary meridians

The eight extraordinary meridians are of pivotal importance in the study of Qigong, Taijiquan and Chinese alchemy.[8] These eight extra meridians differ from the standard twelve organ meridians in that they are considered to be storage vessels or reservoirs of energy and are not associated directly with the Zang Fu, i.e. internal organs. These channels were studied in the "Spiritual Axis" chapters 17, 21 and 62, the "Classic of Difficulties" chapters 27, 28 and 29 and the "Study of the 8 Extraordinary vessels" (Qi Jing Ba Mai Kao), written in 1578.[9]

The eight extraordinary vessels are (奇經八脈; qí jīng bā mài):[10]

- Conception Vessel (Ren Mai) – 任脈; rèn mài

- Governing Vessel (Du Mai) – 督脈; dū mài

- Penetrating Vessel (Chong Mai) – 衝脈; chōng mài

- Girdle Vessel (Dai Mai) – 帶脈; dài mài

- Yin linking vessel (Yin Wei Mai) – 陰維脈; yīn wéi mài

- Yang linking vessel (Yang Wei Mai) – 陽維脈; yáng wéi mài

- Yin Heel Vessel (Yin Qiao Mai) – 陰蹻脈; yīn qiāo mài

- Yang Heel Vessel (Yang Qiao Mai) – 陽蹻脈; yáng qiāo mài

Scientific view of meridian theory

Scientists have found no evidence that supports their existence.[2] The historian of medicine in China Paul U. Unschuld adds that there "is no evidence of a concept of 'energy' -- either in the strictly physical sense or even in the more colloquial sense -- anywhere in Chinese medical theory." [11]

Some advocates of traditional Chinese medicine believe that meridians function as electrical conduits based on observations that the electrical impedance of a current through meridians is lower than other areas of the body. A 2008 review of studies found that the studies were of poor quality and could not support the claims.[12]

Some proponents of the Primo Vascular System propose that the putative primo vessels, very thin (less than 30 μm wide) conduits found in many mammals, may be a factor explaining some of the suggested effects of the meridian system.[13][14]

According to Steven Novella, neurologist involved in the Skeptical movement, "there is no evidence that the meridians actually exist. At the risk of sounding redundant, they are as made up and fictional as the ether, phlogiston, Bigfoot, and unicorns."[1]

The National Council Against Health Fraud concluded that "[t]he meridians are imaginary; their locations do not relate to internal organs, and therefore do not relate to human anatomy."[15]

See also

- Acupuncture point

- Chakra

- List of acupuncture points

- Marma adi

- Nadi (yoga)

- Pressure points

- Glossary of alternative medicine

References

- Novella, Steven (25 January 2012). "What Is Traditional Chinese Medicine?". sciencebasedmedicine.org. Society for Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- Singh, S.; Ernst, E. (2008). Trick Or Treatment: The Undeniable Facts about Alternative Medicine. Norton paperback. W. W. Norton. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-393-06661-6. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Unschuld, Paul U. (2018). Traditional Chinese medicine : heritage and adaptation. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780231175005.

- Standard Acupuncture Nomenclature Archived 2006-03-18 at the Wayback Machine, World Health Organization

- Needham, Joseph; Lu Gwei-Djen (1980). Celestial Lancets. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-521-21513-7.

- Dillman, George and Chris, Thomas. Advanced Pressute Point Fighting of Ryukyu Kempo. A Dillman Karate International Book, 1994. ISBN 0-9631996-3-3

- Peter Deadman and Mazin Al-Khafaji with Kevin Baker. "A Manual of Acupuncture" Journal of Chinese Medicine, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9510546-5-9

- T'ai Chi Ch'uan and Meditation by Da Liu, pages 35–41 – Routledge and Keegan Paul 1987 ISBN 0-14-019217-4

- Ceurvels, Will (2021). An Archaeology of the Qiao Vessels. Purple Cloud Press. ISBN 979-8505103401.

- The foundations of Chinese Medicine by Giovanni Maciocia, pages 355–365 – Churchill Livingstone 1989. ISBN 0-443-03980-1

- Unschuld (2018), p. 125.

- Ahn, Andrew C.; Colbert, Agatha P.; Anderson, Belinda J.; Martinsen, Orjan G.; Hammerschlag, Richard; Cina, Steve; Wayne, Peter M.; Langevin, Helene M. (May 2008). "Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review". Bioelectromagnetics. 29 (4): 245–256. doi:10.1002/bem.20403. ISSN 1521-186X. PMID 18240287.

- Stefanov, Miroslav; Potroz, Michael; Kim, Jungdae; Lim, Jake; Cha, Richard; Nam, Min-Ho (24 October 2013). "The Primo Vascular System as a New Anatomical System". Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies. 6 (6): 331–338. doi:10.1016/j.jams.2013.10.001. ISSN 2005-2901. PMID 24290797.

- Chikly, Bruno; Roberts, Paul; Quaghebeur, Jörgen (January 2016). "Primo Vascular System: A Unique Biological System Shifting a Medical Paradigm". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 116 (1): 12–21. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2016.002. PMID 26745560. S2CID 3809039.

- "NCAHF Position Paper on Acupuncture (1990)". National Council Against Health Fraud. 16 September 1990. Retrieved 13 May 2015.