Microcytic anemia

Microcytic anaemia is any of several types of anaemia characterized by small red blood cells (called microcytes). The normal mean corpuscular volume (abbreviated to MCV on full blood count results, and also known as mean cell volume) is approximately 80–100 fL. When the MCV is <80 fL, the red cells are described as microcytic and when >100 fL, macrocytic (the latter occurs in macrocytic anemia). The MCV is the average red blood cell size.

| Microcytic anaemia | |

|---|---|

| |

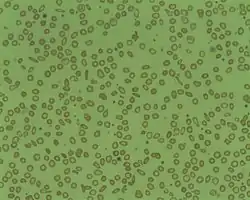

| Microcytosis is the presence of red cells that are smaller than normal. Normal adult red cell has a diameter of 7.2 µm. Microcytes are common seen in with hypochromia in iron-deficiency anaemia, thalassaemia trait, congenital sideroblastic anaemia and sometimes in anaemia of chronic diseases. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

In microcytic anaemia, the red blood cells (erythrocytes) contain less hemoglobin and are usually also hypochromic, meaning that the red blood cells appear paler than usual. This can be reflected by a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), a measure representing the amount of hemoglobin per unit volume of fluid inside the cell; normally about 320–360 g/L or 32–36 g/dL. Typically, therefore, anemia of this category is described as "microcytic, hypochromic anaemia".

Causes

Typical causes of microcytic anemia include:

- Childhood

- Iron deficiency anemia[1] by far the most common cause of anemia in general and of microcytic anemia in particular

- Thalassemia

- Adulthood

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Thalassemia

- Anemia of chronic disease[2]

Rare hereditary causes of microcytic anemia include sideroblastic anemia and other X-linked anemias, hereditary hypotransferrinemia, hereditary aceruloplasminemia, erythropoietic protoporphyria, iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia, and other thalassemic mutations (such as hemoglobin E and hemoglobin Lepore syndrome).[3]

Rare acquired causes of microcytic anemia include lead poisoning, zinc deficiency, copper deficiency, alcohol, and certain medications.[3]

Other causes that are typically thought of as causing normocytic anemia or macrocytic anemia must also be considered, as the presence of two or more causes of anemia can distort the typical picture.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

Nearly half of all anemia cases are due to iron deficiency as it is the most common nutritional disorder.[4] Although it is a common nutritional disorder, most causes of iron deficiency anemia (IDA) are due to blood loss.[4] It is also more common to occur among children and females who are menstruating but can occur to any individual of any age.[5] As well as a low MCV, diagnostic criteria includes low serum ferritin levels and transferrin saturation may also be used.[4] Non-pharmacological measures to treat IDA include increasing sources of dietary iron, especially from heme sources such are liver, seafood, and red meats.[4] However, these measures often take a great deal of time longer to replete iron stores compared to pharmacological agents such as iron supplements which are the mainstay of treatment.[4] Pharmacological agents may also be required in cases where deficiency is more severe, in cases where iron loss exceeds dietary intake, and in individuals who follow a plant-based diet as non-heme sources often have lower bioavailability.[4] When oral iron supplements are used, they should be taken on an empty stomach to increase absorption[4] This might increase the risk of side effects however, such as nausea and epigastric pain.

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Anemia of chronic disease (ACD) is the second most common cause of anemia after IDA.[6] It usually occurs in individuals that have chronic inflammation due to a medical condition.[7] Both diagnosis and treatment can be difficult as there may be an overlap with iron deficiency and thus it is a diagnosis of exclusion.[6][7] Since ACD is caused by an underlying disorder, complete resolution of the condition is unlikely and we focus on controlling the inflammatory disorder rather than treating the ACD itself.[6] Potential inflammatory conditions that can cause ACD are pulmonary tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and malignancies among many others.[7]

Thalassemia

Thalassemia is an inherited condition that has variants in alpha or beta globin genes that result in lower levels of globin chains required to make hemoglobin, resulting in alpha thalassemia or beta thalassemia, respectively.[8] Diagnosis is made by DNA analysis for alpha thalassemia and hemoglobin analysis for beta thalassemia.[8] Management of thalassemia involves chronic transfusions that maintain a hemoglobin level that reduces symptoms of anemia as well as suppresses extramedullary hematopoiesis which can lead to multiple morbidities.[9] Folic acid supplements are also recommended for some cases of thalassemia.[9]

Evaluation and Diagnosis

In theory, the three most common microcytic anemias (iron deficiency anemia, anemia of chronic disease, and thalassemia) can be differentiated by their red blood cell (RBC) morphologies. Anemia of chronic disease shows unremarkable RBCs, iron deficiency shows anisocytosis, anisochromia and elliptocytosis, and thalassemias demonstrate target cells and coarse basophilic stippling. In practice, though elliptocytes and anisocytosis are often seen in thalassemia and target cells occasionally in iron deficiency.[10] All three may show unremarkable RBC morphology. Basophilic stippling is one morphologic finding of thalassemia which does not appear in iron deficiency or anemia of chronic disease. The patient should be in an ethnically at-risk group and the diagnosis is not confirmed without a confirmatory method such as hemoglobin HPLC, H body staining, molecular testing or another reliable method. Coarse basophilic stippling occurs in other cases as seen in Table 1.[10]

As IDA and ACD can often be confused, it is important to evaluate their laboratory parameters. IDA is associated with low hemoglobin, ferritin, transferrin saturation, and MCV.[11] It is also associated with a normal C-reactive protein and high transferrin.[11] ACD is associated as well with low hemoglobin but ferritin may be normal-high, and transferrin saturation, transferrin, and MCV may be low-normal.[11] An additional difference between IDA and ACD is that ACD is often associated with high C-reactive protein.[11]

See also

References

- Iolascon A, De Falco L, Beaumont C (January 2009). "Molecular basis of inherited microcytic anemia due to defects in iron acquisition or heme synthesis". Haematologica. 94 (3): 395–408. doi:10.3324/haematol.13619. PMC 2649346. PMID 19181781.

- Weng, CH; Chen JB; Wang J; Wu CC; Yu Y; Lin TH (2011). "Surgically Curable Non-Iron Deficiency Microcytic Anemia: Castleman's Disease". Onkologie. 34 (8–9): 456–8. doi:10.1159/000331283. PMID 21934347. S2CID 23953242.

- Camaschella, Clara; Brugnara, Carlo (Mar 2022). "Microcytosis/Microcytic anemia". UpToDate. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Lim, Wendy (April 21, 2021). "Common Anemias". Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- Camaschella, Clara; Brugnara, Carlo (Mar 2022). "Microcytosis/Microcytic anemia". UpToDate. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Lim, Wendy (April 21, 2021). "Common Anemias". Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- Camaschella, Clara; Brugnara, Carlo (Mar 2022). "Microcytosis/Microcytic anemia". UpToDate. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Camaschella, Clara; Brugnara, Carlo (Mar 2022). "Microcytosis/Microcytic anemia". UpToDate. Retrieved 2022-04-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Benz, Edward J; Angelucci, Emanuele (Mar 2022). "Management of thalassemia". UpToDate. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- Ford, J. (June 2013). "Red blood cell morphology". International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 35 (3): 351–357. doi:10.1111/ijlh.12082. PMID 23480230.

- Lim, Wendy (April 21, 2021). "Common Anemias". Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Retrieved 2022-04-21.