Musculoskeletal injury

Musculoskeletal injury refers to damage of muscular or skeletal systems, which is usually due to a strenuous activity and includes damage to skeletal muscles, bones, tendons, joints, ligaments, and other affected soft tissues.[3][4] In one study, roughly 25% of approximately 6300 adults received a musculoskeletal injury of some sort within 12 months—of which 83% were activity-related.[3] Musculoskeletal injury spans into a large variety of medical specialties including orthopedic surgery (with diseases such as arthritis requiring surgery), sports medicine,[5] emergency medicine (acute presentations of joint and muscular pain) and rheumatology (in rheumatological diseases that affect joints such as rheumatoid arthritis).

| Musculoskeletal injury | |

|---|---|

| |

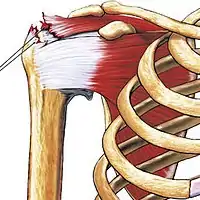

| A rotator cuff tear injury results in the muscles, ligaments and tendons being disturbed which in-turn restricts regular movement. | |

| Specialty | Physiotherapy |

| Symptoms | Mild to severe aches and pains, numbness, weakness, tingling and atrophy |

| Complications | Loss of movement, disability |

| Duration | Dependent on injury, 2-10 weeks[1][2] |

| Types | Bone, muscle, ligament and tendons |

| Causes | overuse, incorrect posture, car accidents, high impact collisions |

| Risk factors | Long term disability |

| Diagnostic method | Pain and numbness |

| Prevention | Maintain correct posture, limit |

| Treatment | Heat and cold packs, immobilisation, rest |

| Deaths | Unknown |

Musculoskeletal injuries can affect any part of the human body including; bones, joints, cartilages, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and other soft tissues.[1] Symptoms include mild to severe aches, low back pain, numbness, tingling, atrophy and weakness.[1][2] These injuries are a result of repetitive motions and actions over a period of time.[6] Tendons connect muscle to bone whereas ligaments connect bone to bone.[7] Tendons and ligaments play an active role in maintain joint stability and controls the limits of joint movements, once injured tendons and ligaments detrimentally impact motor functions.[2][8] Continuous exercise or movement of a musculoskeletal injury can result in chronic inflammation with progression to permanent damage or disability.[9]

In many cases, during the healing period after a musculoskeletal injury, a period in which the healing area will be completely immobile, a cast-induced muscle atrophy can occur. Routine sessions of physiotherapy after the cast is removed can help return strength in limp muscles or tendons. Alternately, there exist different methods of electrical stimulation of the immobile muscles which can be induced by a device placed underneath a cast, helping prevent atrophies[10] Preventative measures include correcting or modifying one’s postures and avoiding awkward and abrupt movements.[1] It is beneficial to rest post injury to prevent aggravation of the injury.[11]

There are three stages of progressing from a musculoskeletal injury; Cause, Disability and Decision.[12] The first stage arises from the injury itself whether it be overexertion, fatigue or muscle degradation.[12] The second stage involves how the individual’s ability is detrimentally affected as disability affects both physical and cognitive functions of an individual.[12][9] The final stage, decision, is the individual’s decision to return to work post recovery as Musculoskeletal injuries compromise movement and physical ability which ultimately degrades one’s professional career.[12]

Repetitive use injuries

Injury can be described as a ‘mechanical disruption of tissues resulting in pain.'[13] Despite the fact tissues can self-repair, muscle degradation occurs after repeated and prolonged use.[13] Overuse and strain injuries can occur at work, physical activity and daily life.[11] Repetitive motions strain our musculoskeletal systems, if continued in an improper form can result in chronic inflammation with progression to permanent damage.[1][6] These injuries can compromise an individual’s posture or other physical abilities, including fine motor movements.[6][1]

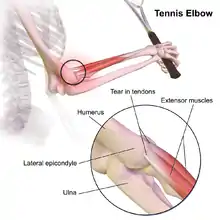

Nerves play an important role in repetitive strain injuries as it is nerves that get pulled in injured soft tissues ultimately affecting motor functions.[2] Pressure on the nerve will impair blood flow which can impair either distal or proximal points to the first injury and cause pain.[8] Tendons connect muscle to bone whereas ligaments connect bone to bone.[7] Tendons and ligaments play an active role in maintain joint stability and controls the limits of joint movements, once injured tendons and ligaments detrimentally impact motor functions.[14][2] Injuries associated with repetitive-use activities include: tennis elbow, tendonitis, wrist injuries, myelopathy, low back injuries and lower leg and ankle injuries.[1]

Repetitive use injuries are a result of rapid and continuous movements, long duration postures without adequate support.[1] Excessive muscle use results in fatigue which limits movement of limbs.[14]

Forms of musculoskeletal injuries

An acute injury can be traced back to a specific incident, causing immediate pain and often swelling.[15][16] On the other hand, a Chronic injury does not have a distinct origin, it develops slowly, is persistent and long lasting, and it is accompanied by dull pain, aches or soreness.[15]

Neck and shoulder injury

The shoulder is a joint which allows your arm to move[2] Poor posture can lead to nerve damage.[2] Repetitive shoulder movements, overhead, swinging, throwing or circling movement can cause musculoskeletal injury.[16] Some cases can result in spinal cord damage at the C3-C5 levels, producing a myelopathy which can dramatically compromise overall movements in arm and legs as well as other fine motor functions.[1] Injury to the rotator cuff Is a result of trauma and old age, complete and partial tears are more frequent in older patients caused by degeneration of the tendons.[7]

Wrist and hand injury

Wrist mobility is often restricted due to inflammation of the forearm muscles as they contract and tighten due to injury.[2] Most wrist dislocations occur between the capitate and the lunate.[17][18] Carpal fractures are caused by falling on an outstretched hand the wrist is hyper-extended in ulnar deviation with a component of rotation.[18] Swelling of the Median nerve tissue leads to nerve entrapment ultimately resulting in restriction of movement, other symptoms include; pain, numbness and weakness.[1] DeQuervain’s Tenosynovitis is a form of tendinitis of the muscles that move the thumb.[2]

Leg and foot injury

Most leg pain is transferred pain from our backs or hips.[1] Foot injuries including plantar fasciitis is another source of pain which is associated with-standing for long periods.[1][6] There are three major tendons that maintain stability at the ankle joint; anterior extensors, medial flexors and lateral peroneal, these tendons facilitate movement around the ankle, foot and toes.[18] Malleolar fractures are related to ankle twisting or shearing injury, these fractures are often associated with ligament injury.[18] An ankle sprain can lead to a spectrum of soft tissue impingement reducing motion in the ankle.[18]

Spinal and neck injury

The spinal column has five sections consisting of thirty three individual vertebrae separated by cushioning discs, the upper three sections are movable and the lower two are fixed.[2] Nerve compression is a result of poor posture, prolonged computer use is an example of repetitive strain injury which affects the musculoskeletal system.[16][2] Whiplash injury, whereby the force causes strain to the capsule and ligaments of the apophyseal joints of the cervical spine.[7] Hyper-flexion is a common mechanism of injury in the cervical spine associated with an anterior compression vector and a posterior distraction vector.[18] These injuries are associated with diving injuries, falls and car accidents.[18] Anterior compression vector results in mild height loss, whereas hyper-extension often occurs with the posterior displacement of the head in car crashes.[18] Severe hyper-extension injury leads to pinching of the spinal cord along the posterior margin of the body.[18]

Elbow injury

The upper arm and the forearm meet to form the elbow joint.[2] Examples of injuries affected on an elbow include; Carpal tunnel syndrome, Radial Tunnel Syndrome and tennis elbow, all of which are due to tendon and ligament damage from overuse or strain.[7][2] Distal humeral fractures are related to high energy trauma from falling from a height or in a motor vehicle accident, this results in stiffness and restricted range of motion.[18] Elbow dislocation and radial head or neck fractures are common when one falls on an outstretched hand.[18] Elbow Dislocations are divided into two categories; Simple and complex. Simple dislocations are defined as soft tissue injury whereas complex involves a fracture.[18]

Injury prevention

Preventing injuries to workers is essential to maintain an effective organisational management.[20] Repetitive injuries can be prevented by early medical intervention as an effective way to prevent permanent injury.[1] Injuries can be prevented by understanding proper body mechanics.[19] Correcting one’s postures, avoiding abrupt and awkward movements will avoid acute injury.[1] Taking breaks to change your position and moving about instead of remaining static can also reduce risk of injury.[21] Daily body stretches can help elevate pain from hamstrings, back and neck.[16] Creating healthy awareness through social media and celebrities further allow individuals to create healthy practices which ultimately prevent injury.[22][23] It is essential for a work environment to comply with safety standards. Workplaces should have upper management implement safety precautions making health and safety the primary goal.[20] Implementation of company policies and procedures in case of serious incident or fatality.[20] Other strategies such as substances abuse programs are effective at reducing the potential for injuries.[20]

If musculoskeletal injuries are not prevented, they can develop and become debilitating.[1] Heat and cold are used to facilitate the healing process, if applied immediately after an acute injury or overuse strain, it will reduce pain and swelling.[8] A healthy workspace is also substantially important including; floor surfaces, ergonomic seating, working heights, working rates and task variability.[16] Understanding the symptoms of repetitive strain injuries such as; Numbness of arms, hands or legs, aches and pains of joints, shoulder and back pain and tingling or burning of arms, legs and feet, allow an individual to self-diagnose and seek medical attention to prevent further aggravation.[1] Pain is the body’s natural way to alert an individual to rest.[2] It is important to rest, if ignored can lead to further problems. It is crucial not to further aggravate the injury and compromise one’s physical movement as it can detrimentally impact general health.[16] Sustaining a secondary injury has a large risk whilst recovering from an initial injury.[21]

Injury recovery

Injuries often limit physical activity and result in immobilisation which is a significant factor in recovery.[16][15] Symptoms vary from, numbness, tingling, atrophy and weakness which can ultimately lead to permanent damage and disability.[9][2] Neural injury recovery in acute strokes are compensated with the help of medical drugs.[24]

Repeating motions and actions whilst performing an activity increases an individual’s risk of accumulating acute musculoskeletal injuries. Factors that affect sustaining these injuries include; duration of activity, the force required to complete the activity, the environment of the workplace and work postures.[1][16] Although, specially advised exercises with stretching promotes blood circulation and increase range of motion and ultimately help decrease muscle tension.[14]

Our immune system is our natural mechanism which manages injuries to the musculoskeletal system. Inflammation, redness, swollen tissue are all part of the healing process, during this process new cells are generated to form new tissue.[15][8] Macro-nutrients are essential components for tissue regeneration.[15] Proteins, carbohydrates and fats are crucial for new muscle tissues. Water allows all biochemical processes to take place including, elimination of waste and toxins via sweat and urination.[16][15]

On the other hand, Micro nutrients include; vitamins, minerals, enzymes, protect cells and DNA from oxidation damages which is evident in the inflammation response and recovery process.[15]

Decision to return to work

Recovery is enhanced by doing activities that make an individual feel better.[25] Recovery from an injury also consists of returning to work or physical exercise. Employers are legally required to provide suitable duties for the person returning to work.[26] It is important to get medical advise on when to return to work.[12] It is important to consider the physical demands of the job, the work environment when deciding to return to work.[27] Once you are approved to return to work or physical exercise it is crucial to maintain both physical and psychological relapse.[12][1]

References

- Siegel, Jerome H. (October 2007). "Risk of Repetitive-Use Syndromes and Musculoskeletal Injuries". Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 9 (4): 200–204. doi:10.1016/j.tgie.2007.08.010.

- Pascarelli, Emil F (2004). Dr. Pascarelli's complete guide to repetitive strain injury what you need to know about RSI and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons. p. 23. ISBN 9780471656197.

- Hootman, Jennifer M.; Macera, Carol A.; Ainsworth, Barbara E.; Addy, Cheryl L.; Martin, Malissa; Blair, Steven N. (May 2002). "Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among sedentary and physically active adults". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 34 (5): 838–844. doi:10.1097/00005768-200205000-00017. PMID 11984303.

- Gimigliano, Francesca; Resmini, Giuseppina; Moretti, Antimo; Aulicino, Milena; Gargiulo, Fiorinda; Gimigliano, Alessandra; Liguori, Sara; Paoletta, Marco; Iolascon, Giovanni (2021-10-17). "Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Adult Athletes: A Scoping Review" (PDF). Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 57 (10): 1118. doi:10.3390/medicina57101118. ISSN 1648-9144. PMC 8539527. PMID 34684155. Archived from the original on 2022-09-05.

- Koutras, Christos; Buecking, Benjamin; Jaeger, Marcus; Ruchholtz, Steffen; Heep, Hansjoerg (November 2014). "Musculoskeletal Injuries in Auto Racing: A Retrospective Study of 137 Drivers". The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 42 (4): 80–86. doi:10.3810/psm.2014.11.2094. PMID 25419891. S2CID 22425278.

- Wardle, Sophie L.; Greeves, Julie P. (November 2017). "Mitigating the risk of musculoskeletal injury: A systematic review of the most effective injury prevention strategies for military personnel". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 20: S3–S10. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2017.09.014. PMID 29103913.

- Crouch, Robert; Charters, Alan; Dawood, Mary; Bennett, Paula, eds. (2016). "Musculoskeletal injuries". Oxford Handbook of Emergency Nursing (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199688869.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-176805-7.

- Frievalds, A. (2011). Biomechanics of the Upper Limbs : Mechanics, Modeling and Musculoskeletal Injuries, Second Edition (2nd edition.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, an imprint of Taylor and Francis.

- Booth-Kewley, Stephanie; Schmied, Emily A.; Highfill-McRoy, Robyn M.; Sander, Todd C.; Blivin, Steve J.; Garland, Cedric F. (June 2014). "A Prospective Study of Factors Affecting Recovery from Musculoskeletal Injuries". Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 24 (2): 287–296. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.995.7437. doi:10.1007/s10926-013-9456-7. PMID 23797182. S2CID 2199186.

- "Casting new energy onto broken limbs - ISRAEL21c". www.israel21c.org. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05.

- Podlog, Leslie; Wadey, Ross; Stark, Andrea; Lochbaum, Marc; Hannon, James; Newton, Maria (July 2013). "An adolescent perspective on injury recovery and the return to sport". Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 14 (4): 437–446. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.12.005.

- Stowell, Anna Wright; McGeary, Donald D. (2008). "Musculoskeletal Injury". In Schultz, Izabela Z.; Gatchel, Robert J. (eds.). Handbook of Complex Occupational Disability Claims: Early Risk Identification, Intervention, and Prevention. Springer. pp. 117–139. doi:10.1007/0-387-28919-4_6. ISBN 978-0-387-28919-9.

- Kumar, Shrawan (January 2001). "Theories of musculoskeletal injury causation". Ergonomics. 44 (1): 17–47. doi:10.1080/00140130120716. PMID 11214897. S2CID 4800520.

- Freivalds, A. (2011). Biomechanics of the Upper Limbs : Mechanics, Modeling and Musculoskeletal Injuries. New York: CRC Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0748409273.

- Chow, Ellen K. (April 2012). "Nutrition for Injury Recovery". Bicycle Paper. Vol. 41, no. 2. p. 6.

- Bradley, David (2014). Managing Minor Musculoskeletal Injuries and Conditions. USA: Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 60. ISBN 9781119105701.

- Donovan, A., & Schweitzer, M. (2012). Imaging musculoskeletal trauma : interpretation and reporting. New York: Wiley.

- Donovan, Andrea; Schweitzer, Mark E. (2012). Imaging musculoskeletal trauma : interpretation and reporting. Chichester: Chichester, West Sussex : Wiley-Blackwell, and imprint of John Wiley & Sons. p. 162. ISBN 9781118551677.

- Doyle, Glynda Rees; McCutcheon, Jodie Anita (2015-11-23). "3.2 Body Mechanics". Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care.

- Hallowell, Matthew R.; Calhoun, Matthew E. (November 2011). "Interrelationships among Highly Effective Construction Injury Prevention Strategies". Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 137 (11): 985–993. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000354.

- Jacobsson, J; Timpka, T; Kowalski, J; Ekberg, J; Nilsson, S; Dahlström, Ö; Renström, P (April 2014). "Subsequent Injury During Injury Recovery In Elite Athletics: Cohort Study In Swedish Male And Female Athletes". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 48 (7): 610.2–611. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093494.137. S2CID 71779348.

- Traffic injury prevention (Online). (2002). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

- Mohan, D., & Tiwari, G. (2014). Injury Prevention and Control. Hoboken: CRC Press.

- Pearson-Fuhrhop, Kristin M; Cramer, Steven C (October 2013). "Pharmacogenetics of neural injury recovery". Pharmacogenomics. 14 (13): 1635–1643. doi:10.2217/pgs.13.152. PMID 24088134.

- Hall, A., Wren, M., & Kirby, S. (2013). Care planning in mental health : promoting recovery. (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.x

- Crichton, Katherine (August 2008). "Returning to work after injury". Manufacturers' Monthly. p. 14. ProQuest 196938923.

- Loisel, Patrick; Anema, Johannes R. (2013). andbook of work disability : prevention and management. New York: New York, NY : Springer. p. 263. ISBN 9781461462149.

External links

- Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders in the Workplace - U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- Musculoskeletal disorders Single Entry Point [[European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)]

- Good Practices to prevent Musculoskeletal disorders [[European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)]

- Musculoskeletal disorders homepage Health and Safety Executive (HSE)

- Hazards and risks associated with manual handling of loads in the workplace [[European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA)]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Musculoskeletal Health Program