PANDAS

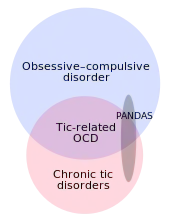

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) is a controversial[1][2] hypothetical diagnosis for a subset of children with rapid onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or tic disorders.[3] Symptoms are proposed to be caused by group A streptococcal (GAS), and more specifically, group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections.[3] OCD and tic disorders are hypothesized to arise in a subset of children as a result of a post-streptococcal autoimmune process.[4][5][6] The proposed link between infection and these disorders is that an autoimmune reaction to infection produces antibodies that interfere with basal ganglia function, causing symptom exacerbations, and this autoimmune response results in a broad range of neuropsychiatric symptoms.[3]

| PANDAS | |

|---|---|

| |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (stained red), a common group A streptococcal bacterium. PANDAS is speculated to be an autoimmune condition in which the body's own antibodies to streptococci attack the basal ganglion cells of the brain, by a concept known as molecular mimicry. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

The PANDAS hypothesis, first described in 1998, was based on observations in clinical case studies by Susan Swedo et al at the US National Institute of Mental Health and in subsequent clinical trials where children appeared to have dramatic and sudden OCD exacerbations and tic disorders following infections.[7] Whether PANDAS was a distinct entity differing from other cases of tic disorders or OCD is debated.[2][8][9] As the PANDAS hypothesis was unconfirmed and unsupported by data, a new definition was proposed by Swedo and colleagues in 2012.[1] In addition to the 2012 broader pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS), two other categories have been proposed: childhood acute neuropsychiatric symptoms (CANS) and pediatric infection-triggered autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders (PITAND).[3] The CANS/PANS hypotheses include different possible mechanisms underlying acute-onset neuropsychiatric conditions, but do not exclude GAS infections as a cause in a subset of individuals.[5][6] PANDAS, PANS and CANS are the focus of clinical and laboratory research but remain unproven.[1][4][5][6]

There is no diagnostic test to accurately confirm PANDAS;[10] the diagnostic criteria are unevenly applied and the conditions may be overdiagnosed.[1] Treatment for children suspected of PANDAS is generally the same as the standard treatments for Tourette syndrome (TS) and OCD.[1] There is insufficient evidence or consensus to support treatment, although experimental treatments are sometimes used,[3] and adverse effects from unproven treatments are expected.[11] The media and the internet have contributed to an ongoing PANDAS controversy,[12][13] with reports of the difficulties of families who believe their children have PANDAS or PANS.[1] Attempts to influence public policy have been advanced by advocacy networks.[1]

Characteristics

The children originally described by Susan Swedo et al. (1998)[14] usually had an abrupt onset of symptoms, including motor or vocal tics, obsessions, or compulsions.[15][16] In addition to an obsessive–compulsive or tic disorder diagnosis, children may have other symptoms associated with exacerbations such as emotional lability, enuresis, anxiety, and deterioration in handwriting.[16] There may be periods of remission.[17] In the PANDAS model, this abrupt onset is thought to be preceded by a strep throat infection. As the clinical spectrum of PANDAS appears to resemble that of Tourette syndrome (TS or TD, for Tourette's disorder), some researchers hypothesized that PANDAS and TS may be associated; this idea is challenged and a focus for research.[8][18][19][20]

Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS)[1][3] is a hypothesized disorder characterized by the sudden onset of OCD symptoms or eating restrictions, concomitant with acute behavioral deterioration or neuropsychiatric symptoms.[1][3] PANS eliminated tic disorders as a primary criterion and placed more emphasis on acute-onset OCD, while allowing for causes other than streptococcal infection.[1]

Classification

PANDAS is hypothesized to be an autoimmune disorder that results in a variable combination of tics, obsessions, compulsions, and other symptoms with sudden or abrupt onset that may be severe enough to qualify for diagnoses such as chronic tic disorder, OCD, and TS.[3][15] As of 2021, the autoimmune hypothesis of PANDAS is not supported by evidence.[1][7][22][23]

PANS, CANS and PITANDs are also hypothesized to be autoimmune disorders.[3]

Cause

The PANDAS diagnosis and the hypothesis that symptoms in this subgroup of patients are caused by infection are disputed and unconfirmed.[1][11][18][20] The cause is thought to be akin to that of Sydenham's chorea (SC), which is known to result from childhood group A streptococcal (GAS) infection leading to the autoimmune disorder rheumatic fever of which SC is one manifestation. Like SC, PANDAS is thought to involve autoimmunity to the brain's basal ganglia.[15][lower-alpha 1]

To establish that a disorder is an autoimmune disorder, the Witebsky criteria require

- that there be a self-reactive antibody,

- that a particular target for the antibody is identified (autoantigen)

- that the disorder can be caused in animals and

- that transferring antibodies from one animal to another triggers the disorder (passive transfer).[24]

Results of studies investigating an autoimmune cause that meet Witebsky's criteria are inconsistent, controversial, and subject to methodological limitations.[8]

To show that a microorganism causes a disorder, the Koch postulates would require one show that the organism is present in all cases of the disorder, that the organism can be extracted from those with the disorder and be cultured, that transferring the organism into healthy subjects causes the disorder, and the organism can be re-isolated from the infected party.[24] Giavanonni notes that the Koch postulates are not useful in substantiating PANDAS a post-infectious disorder because the organism may no longer be present when symptoms emerge, multiple organisms may cause the symptoms, and the symptoms may be a rare reaction to a common pathogen.[24]

Some studies support acute exacerbations associated with streptococcal infections among clinically defined PANDAS subjects; others studies have found no association between abrupt onset or exacerbation with infection.[1][16] The PANS hypothesis, then, expands the causes beyond streptococcal infection and postulates that the cause can be genetic, metabolic, or infectious.[7]

Among children with PANS or PANDAS, studies are inconsistent, and the hypothesis that antibodies trigger symptoms is unproven; some studies showed antibodies in children with PANS/PANDAS, but those results were not replicated in other studies.[1] A large multicenter study (EMTICS—European Multicentre Tics in Children Studies) showed no evidence in children with chronic tic disorders of strep infections leading to tic exacerbation,[7][10] or specific antibodies in children with tics, and a study of the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with TS similarly found no specific antibodies.[10] The antibodies that were found by one group were collectively named the "Cunningham Panel"; subsequent independent testing showed this panel of antibodies did not distinguish between children with and without PANS, and its reliability is unproven.[1][25] A consensus statement from the British Paediatric Neurology Association (BPNA), states that a "causal infection (rather than coincidental infection) or an inflammatory or autoimmune pathogenesis" has not been confirmed, and that "no consistent biomarkers have been identified that accurately diagnose PANDAS or are reliably associated with brain inflammation".[7][4]

Mechanism

The mechanism is hypothesized to be similar to that of rheumatic fever, an autoimmune disorder triggered by streptococcal infections, where antibodies attack the brain and cause neuropsychiatric conditions.[3][16] The molecular mimicry hypothesis is a proposed mechanism for PANDAS:[10] this hypothesis is that antigens on the cell wall of the streptococcal bacteria are similar in some way to the proteins of the heart valve, joints, or brain. Because the antibodies set off an immune reaction which damages those tissues, the child with rheumatic fever can develop Sydenham's.[26] In a typical bacterial infection, the body produces antibodies against the invading bacteria, and the antibodies help eliminate the bacteria from the body. In some rheumatic fever patients, autoantibodies may attack heart tissue, leading to carditis, or cross-react with joints, leading to arthritis.[17] In PANDAS, it is believed that tics and OCD are produced in a similar manner. One part of the brain that may be affected in PANDAS is the basal ganglia, which is believed to be responsible for movement and behavior. It is thought that similar to Sydenham's, the antibodies cross-react with neuronal brain tissue in the basal ganglia to cause the tics and OCD that characterize PANDAS.[10][16][21]

Whether the group of patients diagnosed with PANDAS have developed tics and OCD through a different mechanism (pathophysiology) than seen in other people diagnosed with TS is unclear.[9][27][28][29] Studies of this hypothesis are inconsistent: the strongest supportive evidence comes from a controlled study of 144 children (Mell et al., 2005), but prospective longitudinal studies have not produced conclusive results,[28] and other studies do not support the hypothesis.[10]

Diagnosis

Neither PANDAS nor PANS are listed as a diagnosis in the 2013 fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5)[lower-alpha 2] or confirmed as distinct disorders.[7][8][31][32] PANDAS is mentioned in the World Health Organization's ICD-11, effective in 2022, under autoimmune central nervous system disorders, but diagnostic criteria are not defined and no specific code for PANS or PANDAS is given.[7][33] The 2021 European clinical guidelines developed by the European Society for the Study of Tourette syndrome (ESSTS) did not support the additions made to ICD-11.[34]

Swedo et al in their 1998 paper proposed five diagnostic criteria for PANDAS.[17] According to Lombroso and Scahill (2008), those criteria were: "(1) the presence of a tic disorder and/or OCD consistent with DSM-IV; (2) prepubertal onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms; (3) a history of a sudden onset of symptoms and/or an episodic course with abrupt symptom exacerbation interspersed with periods of partial or complete remission; (4) evidence of a temporal association between onset or exacerbation of symptoms and a prior streptococcal infection; and (5) adventitious movements (e.g., motoric hyperactivity and choreiform movements) during symptom exacerbation".[17]

The proposed PANS criteria call for abrupt onset of OCD (severe enough to warrant a DSM diagnosis) or restricted food intake, along with severe and acute neuropsychiatric symptoms from at least two of the following: anxiety, emotional lability or depression, irritability or oppositional behaviors, developmental regression, academic deterioration, sensory or motor difficulties, or sleep or urinary disturbances. The symptoms should not be better explained by another disorder, such as Syndenham chorea or Tourette syndrome.[1] The authors stated that all other causes must be excluded (diagnosis of exclusion) for PANS to be considered.[7]

There is no diagnostic test to accurately confirm PANDAS.[10] The diagnostic criteria of all the proposed conditions (PANDAS, PITANDs, CANS and PANS) are based on symptoms and presentation, rather than on signs of autoimmunity.[3] A commercial tool known as the "Cunningham Panel" and marketed by Moleculera Labs—intended to diagnose PANDAS and PANS based on assays of antibodies—did not distinguish between children with and without PANS when independently tested.[1][10][lower-alpha 3]

PANDAS may be overdiagnosed: the diagnostic criteria are unevenly applied and a presumed diagnosis may be conferred in "children in whom immune-mediated symptoms are unlikely",[1] according to Wilbur et al (2019). Most patients diagnosed with PANDAS by community physicians did not meet the criteria when examined by specialists, suggesting the PANDAS diagnosis is conferred by community physicians without conclusive evidence.[37][10][28]

Because symptoms overlap with many other psychiatric conditions, differential diagnosis is challenging.[3] There are several difficulties in distinguishing PANDAS from TS. The two have a similar onset and waxing and waning course, and the sudden onset or exacerbation in tics hypothesized in PANDAS is not uncommon in TS. There is a higher rate of OCD and TS among relatives of children with PANDAS, and those children often have tics preceding a PANDAS diagnosis or may be predisposed to tic disorders; what appears to be a dramatic onset due to GAS infection "may be the natural course of tic disorders", according to Ueda and Black (2021).[10]

Treatment

Treatment for children suspected of PANDAS is generally the same as the standard treatments for TS and OCD.[1][12][38] These include cognitive behavioral therapy and medications to treat OCD such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs);[1] and "conventional therapy for tics".[38]

When individuals have "persistent or disabling symptoms", Wilbur (2019) et al recommend referral to specialists, treatment of identified acute streptococcal infections according to established guidelines, and immunotherapy only in clinical trials.[1]

The use of psychotropic medications for PANS/PANDAS is widespread, although controlled trials were lacking as of 2019.[1]

Experimental

Prophylactic antibiotic treatments for tics and OCD are experimental[37] and their use is challenged;[28] overdiagnosis of PANDAS may have led to overuse of antibiotics to treat tics or OCD in the absence of active infection.[28] Evidence for antibiotic treatment is inconclusive for PANS, PANDAS, PITAND and CANS.[3] Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman (2010) said, "The use of prophylactic antibiotics to treat PANDAS has become widespread in the community, although the evidence supporting their use is equivocal."[12]

As of 2019, there is no evidence supporting the use rituximab or mycophenolate mofetil for treating PANDAS/PANS.[1]

There is inconclusive evidence supporting immunomodulatory therapies (intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE)[16]) for PANS and PANDAS; most studies have methodological issues.[3] IVIG was perceived as effective based on a self-reported survey.[3] Kalra and Swedo wrote in 2009, "Because IVIG and plasma exchange both carry a substantial risk of adverse effects, use of these modalities should be reserved for children with particularly severe symptoms and a clear-cut PANDAS presentation."[29]

Studies of experimental treatments for PANS and PANDAS (IVIG, TPE, antibiotics, tonsillectomy, corticosteroids and NSAIDs) are "few and in general have moderate or high risk of bias", according to a Sigra et al review published in 2018, which states:[3]

Nevertheless, there are 3 recent papers proposing guidelines for how to treat PANDAS and PANS using psychiatric and behavioral interventions (Thienemann et al., 2017), immunomodulatory therapies (Frankovich et al., 2017) and antibiotics (Cooperstock et al., 2017). These guidelines are proposed by a consortium of clinicians and researchers ... for children who fulfill criteria for PANDAS or PANS. We believe that our results are in line with the proposed guidelines, and that the lack of evidence for treatment is based not on the inefficacy of the treatments, but on lack of systematic research.

— Sigra et al (2018)[3]

Guidelines

Following a 2014 meeting in the US of Swedo and physicians from Stanford University,[7] treatment guidelines for PANS and PANDAS were published in 2017, in three parts.[39][40][41] In a 2018 review, Sigra et al said of the 2017 guidelines that treatment consensus was lacking and that results were inconclusive.[3] A 2019 review by Wilbur et al said that evidence for treatment of children with PANDAS/PANS is lacking, and remission rates in symptoms after treatment "may represent the natural history of [non-PANDAS pediatric OCD] cases rather than true treatment effect".[1] The Wilbur et al 2019 review found no evidence to support tonsillectomy or prophylactic antibiotics, recommended standard approved therapies known to be effective for OCD, and cautioned against immunomodulatory therapies except in clinical trials.[1] Gilbert (2019) stated: "Skeptics have concluded that treatment studies do not support antibiotic or immunomodulatory interventions for PANDAS. Advocates published treatment guidelines supporting both."[32]

The guideline status in the UK is similar. The PANDAS and PANS Physicians Network published guidelines in 2018 on a private healthcare platform, e-hospital.[42] In April 2021, the British Paediatric Neurology Association (BPNA) issued a consensus statement with the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists stating that there is an absence of evidence for recommending immunomodulatory or prophylactic antibiotic treatments.[7] This consensus statement was issued in place of a guideline as the authors stated that there was insufficient evidence for developing a typical guideline.[7] It noted no previous guidelines for PANDAS existed or had been endorsed by official bodies in the UK, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and that the 2018 guidelines available at a PANDAS/PANS UK charity website and the private platform (e-hospital) had been developed independently of the BPNA.[7]

Similarly, the April 2021 treatment guidelines for Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK) do not recommend tonsillectomy, antibiotic prophylaxis, or experimental immunomodulatory therapies outside of a specialist setting.[43] A Swedish review published in 2021 found a moderate potential for adverse effects, and a "very low certainty of evidence of beneficial effects", for treating individuals meeting the research definition of PANS with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications, or immunomodulatory agents.[11] The Swedish review states that, "some researchers in the United States, on the basis of an assumption of an underlying neuroinflammation, recommend anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and immunomodulatory treatment in the clinical management of these patients, Swedish national guidelines imply that these treatments shall only be provided within the framework of research and development".[11]

The American Academy of Neurology 2011 guidelines say there are "inadequate data to determine the efficacy of plasmapheresis" and "insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of plasmapheresis", for treating OCD and tics "in the setting of PANDAS".[19] The Medical Advisory Board of the Tourette Syndrome Association (now the Tourette Association of America) said in 2006,[44] and reiterated in 2021:[10][45]

"Treatment with antibiotics should not be initiated without clinical evidence of infection and a positive throat culture. Experimental treatments based on the autoimmune theory, such as plasma exchange, immunoglobulin therapy, or prophylactic antibiotic treatment, should not be undertaken outside of formal clinical trials."

The American Heart Association's 2009 guidelines state that they do "not recommend routine laboratory testing for GAS to diagnose, long-term antistreptococcal prophylaxis to prevent, or immunoregulatory therapy (such as intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange) to treat exacerbations of this disorder".[46]

Society and culture

The debate surrounding the PANDAS hypothesis has societal implications; the media and the Internet have played a role in the PANDAS controversy.[12][13] The news and other media report the difficulties of families who believe their children have PANDAS or PANS.[1] Attempts to influence public policy have been advanced by advocacy networks such as the USA-based PANDAS Network and Canadian PANDASHELP.[1]

Swerdlow (2005) summarized the societal implications of the hypothesis, and the role of the Internet in the debate surrounding the PANDAS hypothesis:

... perhaps the most controversial putative TS trigger is exposure to streptococcal infections. The ubiquity of strep throats, the tremendous societal implications of over-treatment (e.g., antibiotic resistance or immunosuppressant side effects) versus medical implications of under-treatment (e.g., potentially irreversible autoimmune neurologic injury) are serious matters. With the level of desperation among Internet-armed parents, this controversy has sparked contentious disagreements, too often lacking both objectivity and civility.[13]

Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman (2010) discussed the influence of the media and the Internet in a paper that proposed a "way forward" with the "group of disorders collectively described as PANDAS":

Of concern, public awareness has outpaced our scientific knowledge base, with multiple magazine and newspaper articles and Internet chat rooms calling this issue to the public's attention. Compared with ~ 200 reports listed on Medline—many involving a single patient, and others reporting the same patients in different papers, with most of these reporting on subjects who do not meet the current PANDAS criteria—there are over 100,000 sites on the Internet where the possible Streptococcus–OCD–TD relationship is discussed. This gap between public interest in PANDAS and conclusive evidence supporting this link calls for increased scientific attention to the relationship between GAS and OCD/tics, particularly examining basic underlying cellular and immune mechanisms.[12]

History

PANDAS was first described in 1998[3] by Susan Swedo and a group of researchers[7] at the US National Institute of Mental Health (a branch of the NIH).[15] A similar clinical picture was proposed for PITANDs (pediatric infection-triggered autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders) for those who met the Swedo et al criteria for PANDAS, but with symptoms triggered by an infection other than GAS.[3]

Michael Pichichero (2009) noted several reasons that PANDAS had not been validated as a disease classification. Its proposed age of onset and clinical features reflected a particular group of patients chosen for research studies, with no systematic studies of the possible relationship of GAS to other neurologic symptoms. There was dispute over whether its symptom of choreiform movements was distinct from the similar movements of SC. It was not known whether the pattern of abrupt onset was specific to PANDAS. Finally, there was controversy over whether a temporal relationship between GAS infections and PANDAS symptoms existed.[15]

In light of controversies in establishing a basis for the hypothesis, a 2010 paper calling for "a way forward", Murphy, Kurlan and Leckman said: "It is time for the National Institutes of Health, in combination with advocacy and professional organizations, to convene a panel of experts not to debate the current data, but to chart a way forward. For now we have only to offer our standard therapies in treating OCD and tics, but one day we may have evidence that also allows us to add antibiotics or other immune-specific treatments to our armamentarium."[12] A 2011 paper by Singer proposed CANS, childhood acute neuropsychiatric symptoms—a new, "broader concept" in favor or requiring only acute-onset.[47] CANS removes the requirement for GAS infection,[3] allowing for multiple causes, which Singer proposed because of the "inconclusive and conflicting scientific support" for PANDAS, including "strong evidence suggesting the absence of an important role for GABHS, a failure to apply published [PANDAS] criteria, and a lack of scientific support for proposed therapies".[47]

By 2012, with limitations of the PANDAS hypothesis published, the broader pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) was proposed (also by Swedo and colleagues, following a conference[7]) to create a better defined condition for research purposes.[1] It describes individuals with eating disorders or rapid onset of OCD along with other neuropsychiatric symptoms,[3] and postulates that the causes can be other than GAS.[7] The term pediatric was chosen over childhood because some cases described at the conference included adolescents. Whether the PANS hypothesis defines a distinct entity is unclear as of 2019.[1]

Swedo retired from the NIH in 2019, but serves on the scientific advisory board of the PANDAS Physician Network.[48] As of 2020, the NIH information pages (which Swedo helped write) do not mention the studies that do not support the PANDAS hypothesis.[48]

See also

Notes

- Unlike SC, PANDAS is not associated with other manifestations of acute rheumatic fever, such as inflammation of the heart.[15]

- Swedo served as the chair of the Neurodevelopmental Disorders Work Group on the DSM-5 Task Force.[30]

- See 2017 study of the Cunningham Panel[35] and erratum based on collection tubes.[36]

References

- Wilbur C, Bitnun A, Kronenberg S, Laxer RM, Levy DM, Logan WJ, Shouldice M, Yeh EA (May 2019). "PANDAS/PANS in childhood: Controversies and evidence". Paediatr Child Health. 24 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1093/pch/pxy145. PMC 6462125. PMID 30996598.

- Hsu CJ, Wong LC, Lee WT (January 2021). "Immunological dysfunction in Tourette syndrome and related disorders". Int J Mol Sci (Review). 22 (2): 853. doi:10.3390/ijms22020853. PMC 7839977. PMID 33467014.

- Sigra S, Hesselmark E, Bejerot S (March 2018). "Treatment of PANDAS and PANS: a systematic review". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 86: 51–65. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.001. PMID 29309797. S2CID 40827012.

- Dale RC (December 2017). "Tics and Tourette: a clinical, pathophysiological and etiological review". Curr Opin Pediatr (Review). 29 (6): 665–673. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000546. PMID 28915150. S2CID 13654194.

- Marazziti D, Mucci F, Fontenelle LF (July 2018). "Immune system and obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychoneuroendocrinology (Review). 93: 39–44. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.013. PMID 29689421. S2CID 13681480.

- Zibordi F, Zorzi G, Carecchio M, Nardocci N (March 2018). "CANS: Childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndromes". Eur J Paediatr Neurol (Review). 22 (2): 316–320. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.01.011. PMID 29398245.

- "Consensus statement on childhood neuropsychiatric presentations, with a focus on PANDAS/PANS" (PDF). British Paediatric Neurology Association. April 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021. See summary here.

- Chiarello F, Spitoni S, Hollander E, Matucci Cerinic M, Pallanti S (June 2017). "An expert opinion on PANDAS/PANS: highlights and controversies". Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 21 (2): 91–98. doi:10.1080/13651501.2017.1285941. PMID 28498087. S2CID 3457971.

- Robertson MM (February 2011). "Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the complexities of phenotype and treatment" (PDF). Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 72 (2): 100–7. doi:10.12968/hmed.2011.72.2.100. PMID 21378617.

- Ueda K, Black KJ (June 2021). "A Comprehensive Review of Tic Disorders in Children". J Clin Med. 10 (11): 2479. doi:10.3390/jcm10112479. PMC 8199885. PMID 34204991.

- Johnson M, Ehlers S, Fernell E, Hajjari P, Wartenberg C, Wallerstedt SM (2021). "Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and immunomodulatory treatment in children with symptoms corresponding to the research condition PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome): A systematic review". PLOS ONE. 16 (7): e0253844. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1653844J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253844. PMC 8248649. PMID 34197525.

- Murphy TK, Kurlan R, Leckman J (August 2010). "The immunobiology of Tourette's disorder, pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with Streptococcus, and related disorders: a way forward". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 20 (4): 317–31. doi:10.1089/cap.2010.0043. PMC 4003464. PMID 20807070.

- Swerdlow NR (September 2005). "Tourette syndrome: current controversies and the battlefield landscape" (PDF). Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 5 (5): 329–31. doi:10.1007/s11910-005-0054-8. PMID 16131414. S2CID 26342334.

- Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al. (February 1998). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 cases". Am J Psychiatry. 155 (2): 264–71. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.2.264. PMID 9464208. S2CID 22081877.

- Pichichero ME (2009). "The PANDAS syndrome". Hot Topics in Infection and Immunity in Children V. Adv Exp Med Biol. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 634. Springer. pp. 205–16. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79838-7_17. ISBN 978-0-387-79837-0. PMID 19280860.

PANDAS is not yet a validated nosological construct.

Courtesy link to partial pages. - Moretti G, Pasquini M, Mandarelli G, Tarsitani L, Biondi M (2008). "What every psychiatrist should know about PANDAS: a review". Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 4 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-4-13. PMC 2413218. PMID 18495013.

- Lombroso PJ, Scahill L (2008). "Tourette syndrome and obsessive–compulsive disorder". Brain Dev. 30 (4): 231–7. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2007.09.001. PMC 2291145. PMID 17937978.

- Boileau B (2011). "A review of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 13 (4): 401–11. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/bboileau. PMC 3263388. PMID 22275846.

- Cortese I, Chaudhry V, So YT, Cantor F, Cornblath DR, Rae-Grant A (January 2011). "Evidence-based guideline update: Plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 76 (3): 294–300. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318207b1f6. PMC 3034395. PMID 21242498.

- Felling RJ, Singer HS (August 2011). "Neurobiology of Tourette syndrome: current status and need for further investigation". J. Neurosci. 31 (35): 12387–95. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0150-11.2011. PMC 6703258. PMID 21880899.

- Leckman JF, Bloch MH, King RA (2009). "Symptom dimensions and subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a developmental perspective". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 11 (1): 21–33. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/jfleckman. PMC 3181902. PMID 19432385.

- Szejko N, Robinson S, Hartmann A, et al. (October 2021). "European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders-version 2.0. Part I: assessment". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 31 (3): 383–402. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01842-2. PMC 8521086. PMID 34661764.

- Nielsen MØ, Köhler-Forsberg O, Hjorthøj C, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, Orlovska-Waast S (February 2019). "Streptococcal Infections and Exacerbations in PANDAS: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 38 (2): 189–194. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002218. PMID 30325890. S2CID 53523695.

- Giavannoni G (2006). PANDAS: overview of the hypothesis. Adv Neurol. Vol. 99. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 159–65. ISBN 978-0-7817-9970-6. PMID 16536362. Courtesy link to pp. 159–62.

- Martino D, Johnson I, Leckman JF (2020). "What Does Immunology Have to Do With Normal Brain Development and the Pathophysiology Underlying Tourette Syndrome and Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders?". Front Neurol (Review). 11: 567407. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.567407. PMC 7525089. PMID 33041996.

- Bonthius D, Karacay B (2003). "Sydenham's chorea: not gone and not forgotten". Semin Pediatr Neurol. 10 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1016/S1071-9091(02)00004-9. PMID 12785743.

- Singer HS (2011). "Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders". Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 100. pp. 641–57. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00046-X. ISBN 9780444520142. PMID 21496613.

- Leckman JF, Denys D, Simpson HB, et al. (June 2010). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review of the diagnostic criteria and possible subtypes and dimensional specifiers for DSM-V". Depress Anxiety. 27 (6): 507–27. doi:10.1002/da.20669. PMC 3974619. PMID 20217853.

- Kalra SK, Swedo SE (April 2009). "Children with obsessive-compulsive disorder: are they just "little adults"?". J. Clin. Invest. 119 (4): 737–46. doi:10.1172/JCI37563. PMC 2662563. PMID 19339765.

- "Susan Swedo, M.D." American Psychiatric Association. Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Nazeer A, Latif F, Mondal A, Azeem MW, Greydanus DE (February 2020). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: epidemiology, diagnosis and management". Transl Pediatr. 9 (Suppl 1): S76–S93. doi:10.21037/tp.2019.10.02. PMC 7082239. PMID 32206586.

- Gilbert DL (September 2019). "Inflammation in Tic Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Are PANS and PANDAS a Path Forward?". J Child Neurol. 34 (10): 598–611. doi:10.1177/0883073819848635. PMC 8552228. PMID 31111754.

- "8E4A.0 Paraneoplastic or Autoimmune Disorders of the Central Nervous System, Brain or Spinal Cord". ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. World Health Organization. May 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Müller-Vahl KR, Szejko N, Verdellen C, et al. (July 2021). "European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: summary statement". Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 31 (3): 377–382. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01832-4. PMC 8940881. PMID 34244849. S2CID 235781456.

- Hesselmark E, Bejerot S (November 2017). "Biomarkers for diagnosis of Pediatric Acute Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) - Sensitivity and specificity of the Cunningham Panel". J Neuroimmunol. 312: 31–37. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.09.002. PMID 28919236. S2CID 24495364.

- Hesselmark E, Bejerot S (December 2017). "Corrigendum to Biomarkers for diagnosis of Pediatric Acute Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) - Sensitivity and specificity of the Cunningham Panel [J. Neuroimmunol. 312. (2017) 31-37]". J Neuroimmunol. 313: 116–117. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.11.001. PMID 29153602. S2CID 7958313.

We have evaluated the clinical value of the Cunningham Panel as a diagnostic tool. Our results indicate that the panel does not contribute to correct diagnosis in a clinical setting.

- Shulman ST (February 2009). "Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS): update". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 21 (1): 127–30. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32831db2c4. PMID 19242249. S2CID 37434919.

Despite continued research in the field, the relationship between GAS and specific neuropsychiatric disorders (PANDAS) remains elusive.

See lay summary PANDAS May Be Overdiagnosed, Contributing to Overuse of Antibiotics, Medscape, October 26, 2006. - de Oliveira SK, Pelajo CF (March 2010). "Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infection (PANDAS): a Controversial Diagnosis". Curr Infect Dis Rep. 12 (2): 103–9. doi:10.1007/s11908-010-0082-7. PMID 21308506. S2CID 30969859.

- Thienemann M, Murphy T, Leckman J, Shaw R, Williams K, Kapphahn C, Frankovich J, Geller D, Bernstein G, Chang K, Elia J, Swedo S (September 2017). "Clinical Management of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Part I-Psychiatric and Behavioral Interventions". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 27 (7): 566–573. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0145. PMC 5610394. PMID 28722481.

- Frankovich J, Swedo S, Murphy T, et al. (September 2017). "Clinical management of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: part II—use of immunomodulatory therapies". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 27 (7): 574–593. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0148.

- Cooperstock MS, Swedo SE, Pasternack MS, Murphy TK (September 2017). "Clinical management of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: part III—treatment and prevention of infections". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 27 (7): 594–606. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0151.

- UK PANDAS & PANS Physicians Network (November 2018). "PANDAS & PANS Treatment Guidelines (v1.6)" (PDF). e-hospital.co.uk. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Pfeiffer HC, Wickstrom R, Skov L, Sørensen CB, Sandvig I, Gjone IH, Ygberg S, de Visscher C, Idring Nordstrom S, Herner LB, Hesselmark E, Hedderly T, Lim M, Debes NM (April 2021). "Clinical guidance for diagnosis and management of suspected Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome in the Nordic countries". Acta Paediatr. 110 (12): 3153–3160. doi:10.1111/apa.15875. PMID 33848371. S2CID 233234801.

- Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM, et al. (April 2006). "Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome". NeuroRx. 3 (2): 192–206. doi:10.1016/j.nurx.2006.01.009. PMC 3593444. PMID 16554257.

- TAA PANDAS/PANS Workgroup. "PANDAS/PANS and Tourette Syndrome (Disorder)". Tourette Association of America. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. (March 2009). "Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute Streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics". Circulation. 119 (11): 1541–51. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.191959. PMID 19246689.

- Singer HS, Gilbert DL, Wolf DS, Mink JW, Kurlan R (December 2011). "Moving from PANDAS to CANS". J Pediatr. 160 (5): 725–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.040. PMID 22197466.

- Borrell, Brendan (January 2020). "How a controversial condition called PANDAS is gaining ground on autism". Spectrum News. Simons Foundation. Retrieved November 23, 2021.