Sewage farm

Sewage farms use sewage for irrigation and fertilizing agricultural land. The practice is common in warm, arid climates where irrigation is valuable while sources of fresh water are scarce. Suspended solids may be converted to humus by microbes and bacteria in order to supply nitrogen, phosphorus and other plant nutrients for crop growth. Many industrialized nations use conventional sewage treatment plants nowadays instead of sewage farms. These reduce vector and odor problems; but sewage farming remains a low-cost option for some developing countries. Sewage farming should not be confused with sewage disposal through infiltration basins or subsurface drains.

Advantages

Sewage farming allows use for irrigation of water which might otherwise be wasted. Some of the nutrients and organic solids in wastewater can be usefully incorporated into soil and agricultural products rather than fouling natural aquatic environments. Pumping to the point of application may be the only requirement if the village is not at a higher elevation than the sewage farm.[1]

Disadvantages

Polluted runoff may occur from sewage irrigation of fields when entering wastewater and precipitation exceed evaporation and percolation capacity.[2]

Sewage is usually generated at a relatively constant rate, but irrigation is required only during dry weather, and is useful only while temperatures are high enough to promote plant growth. Over-irrigation causes soils to become septic, sour, or sewage-sick.[2] Arid climates may allow temporary storage of sewage in holding ponds while the soils dry out during non-growing seasons, but such storage may cause odor and aquatic insect problems, including mosquitoes.[1]

It may be impractical to protect the crops being grown from sewage contact. Even optimum situations like irrigating fruit trees with flow in surface ditches may involve some risk of pathogen transfer from the sewage to the edible fruit by birds, insects, and similar vectors. Pathogen transfer is more likely with ground crops, and practically unavoidable with spray irrigation.[2]

Similar wastewater systems

Subsurface distribution piping is problematic since it is vulnerable to root blockage and to damage during soil cultivation. Also obstruction of distribution piping by sewage solids discourages sewage farming when wastewater is not pre-treated as it is typically the case in a septic drain field.

Sewage farming should not be confused with wastewater disposal through infiltration basins or subsurface drains.

Plows or harrows may be used to periodically break up vegetation mats which are slowing surface disposal.[3]

Subsurface disposal typically uses pipes placed deep enough to minimize root penetration and often manages overlying vegetation to avoid growth of plants with deep root systems.[4]

History

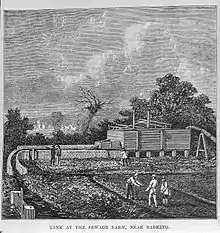

As a predecessor to modern sewage treatment systems, household sewage was collected from towns and cities and transported to nearby farm lands. During the Middle Ages this was accomplished with hand-carried buckets, but as local populations grew, during the Industrial Revolution sanitary sewer systems were built. These used a network of pipes and pumps to transport sewage beyond the city boundaries to large rented grasslands, into which the sewage trickled down. Berlin once operated 20 sewage farms occupying about 10,000 hectares.[5]

In Wales, it was the common means of sewage treatment when cess-pits became unusable as the population grew in towns during the industrial revolution.[6] The initial response to overloaded local disposal was often a trunk sewer conveying sewage to the nearest river but as populations increased further, sewage farms were established.[7]

Some of these farms remained in use until the end of the 20th century, at which point it became apparent that as it was usually contaminated with infectious pathogens and sometimes with industrial waste, sewage was not always suitable for use as a fertilizer. Therefore, sewage plants began to replace sewage farms. Modern sewage farms are usually combined with such plant, so that they irrigate the land with treated sewage (reclaimed water). Some types of untreated sewage can be used on a sewage farm, or filtered through a constructed wetland.

Examples

- A small-scale example of a sewage farm exists at Chester Zoo, where water fouled with elephant droppings and urine is filtered through a reedbed.

- Western Treatment Plant in Melbourne.

See also

References

- Hutchins, Wells A. (March 1939). Sewage Irrigation as Practiced in the Western States. Washington DC: United States Department of Agriculture.

- Fair, Gordon Maskew; Geyer, John Charles; Okun, Daniel Alexander (1968). Water and Wastewater Engineering: Water Purification and Wastewater Treatment and Disposal. Vol. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 35-3.

- Reed, Sherwood C.; Middlebrooks, E. Joe; Crites, Ronald W. (1988). Natural Systems for Waste Management & Treatment. McGraw-Hill. pp. 220&246. ISBN 0-07-051521-2.

- Alth, Max & Charlotte (1984). Constructing & Maintaining Your Well & Septic System (First ed.). Tab Books. p. 213. ISBN 0-8306-0654-8.

- de:Berliner Rieselfelder

- "Welsh History Review - Vol. 14, nos. 1-4 1988-89 Merthyr Tydfil in the mid-Nineteenth Century: the struggle for public health". The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- David Williams (1991). "The rehabilitation of the River Taff". National Rivers Authority. Retrieved 29 October 2016.