Suicide in the United States

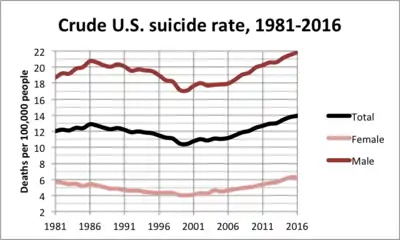

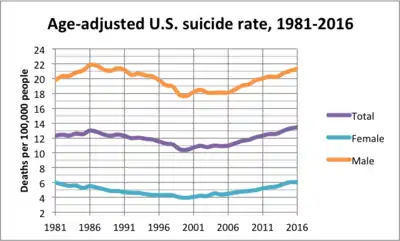

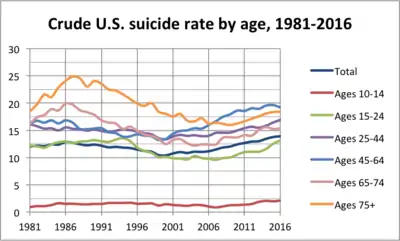

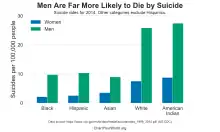

Suicide in the United States is a major national public health issue. The country has one of the highest suicide rates among wealthy nations.[2] In 2020, there were 45,799 recorded suicides,[3] up from 42,773 in 2014, according to the CDC's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).[4][5][6] On average, adjusted for age, the annual U.S. suicide rate increased 30% between 2000 and 2020, from 10.4 to 13.5 suicides per 100,000 people.[7] In 2018, 14.2 people per 100,000 died by suicide, the highest rate recorded in more than 30 years.[8][9] Due to the stigma surrounding suicide, it is suspected that suicide is generally underreported.[10] In April 2016, the CDC released data showing that the suicide rate in the United States had hit a 30-year high,[11][12] and later in June 2018, released further data showing that the rate has continued to increase and has increased in every U.S. state except Nevada since 1999.[13][14] From 2000 to 2020, more than 800,000 people died by suicide in the United States, with males representing 78.7% of all suicides that happened between 2000 and 2020.[3] Surging death rates from suicide, drug overdoses and alcoholism, what researchers refer to as "deaths of despair", are largely responsible for a consecutive three year decline of life expectancy in the U.S.[15][16][17][18] This constitutes the first three-year drop in life expectancy in the U.S. since the years 1915–1918.[17]

In 2015, suicide was the seventh leading cause of death for males and the 14th leading cause of death for females.[19] Additionally, it was the second leading cause of death for young people aged 10 to 34.[20] From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate among Americans aged 35 to 64 increased nearly 30 percent. The largest increases were among women aged 60 to 64, with rates rising 60 percent, then men in their fifties, with rates rising nearly 50 percent.[9] In 2008, it was observed that U.S. suicide rates, particularly among middle-aged white women, had increased, although the causes were unclear.[21] As of 2018, about 1.7 percent of all deaths were suicides.[3]

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention reported that in 2016 suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S., imposing a cost of $69 billion to the US annually.[10][19] Other statistics reported are:[10]

- The annual age-adjusted suicide rate is 13.42 per 100,000 individuals.

- Males die by suicide 3.5 times more often than females.

- On average, there are 132 suicides per day.

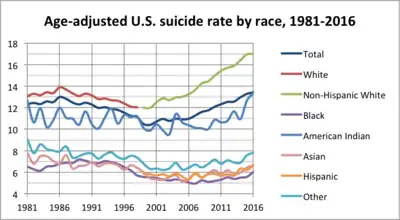

- White males accounted for 7 of 10 suicides in 2016.

- A firearm is used in almost 50% of all suicides.

- The rate of suicide is highest in middle age—among white men in particular.

The U.S. government seeks to prevent suicides through its National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, a collaborative effort of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Indian Health Service.[22] Their plan consists of eleven goals aimed at preventing suicides.[23] Older adults are disproportionately likely to die by suicide.[24] Some U.S. jurisdictions have laws against suicide or against assisting suicide. In recent years, there has been increased interest in rethinking these laws.[25]

Suicide has been associated with tough economic conditions, including unemployment rate.[26]

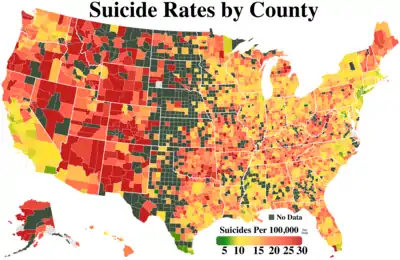

There are significant variations in the suicide rates of the different states,[27] ranging from 28.89 per 100,000 people in Montana to 8.11 per 100,000 people in New York.[10]

A firearm is used in approximately half of suicides, accounting for two-thirds of all firearm deaths.[28] Firearms were used in 56.9% of suicides among males in 2016, making it the most commonly used method by them.[19]

On July 16th 2022, the United States transitioned the National Suicide Hotline from the former 10-digit number into the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, linking both the National Suicide Hotline, the Veterans Crisis Line, and a network of more than 200 state and local call centers run through SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.[29]

Trends in suicide attempts

The spike in suicide rates in the United States during the 21st century has gained public and clinical attention. Studies have found that despite efforts to minimize suicide rates, rates have steadily increased by approximately 2% per year from 2006 to 2014.[30] A national epidemiologic survey of 69,341 US adults found the percentage of adults attempting suicide increased from 0.62% in 2004 through 2005 to 0.79% in 2012 through 2013.[31] Because of this, clinicians aim to determine whether this is a coincident national increase in suicide attempts. In order to achieve this, trends in suicide attempts are characterized among sociodemographic and clinical groups. It was found that suicide attempts impact "younger adults with less formal education and those with antisocial personality disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and a history of violence” at disproportional rates.[31] It is important for trends in suicide attempts to be investigated and researched for they help to determine the cause of the increase in suicide rates. Knowing the trends in suicide also allow preventative measures to be taken. Suicide prevention is possible through early identification and treatment of individuals deemed high risk.[32]

Suicide as a public health issue

Suicide prevention has been thought of as the responsibility of mental health professionals within clinical settings between 2000–2010.[33] As of 2019, suicide prevention is being recognized as a public health responsibility rather than within clinical settings due to the trend in increasing suicide rates.[34] In 1960–2010, population-based risk reduction approaches have been used for other diseases such as myocardial infarction. However, as of 2019, the urgency of development of effective suicide prevention has been recognized by the CDC. While suicide is often thought of as an individual problem, suicides may impact families, communities, and society in general. The responsibility of public health would be to develop policies to reduce people's risk of suicidal behavior through addressing factors at the individual to societal levels.[34] "Public health emphasizes efforts to prevent violence (in this case, toward oneself) before it happens. This approach requires addressing factors that put people at risk for, or protect them from, engaging in suicidal behavior."[34]

The CDC has created a National Suicide Prevention Lifeline where they provide free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for people who are in need of such help, and best practices for professionals.[35] In May 2019, Bloomberg reported that in spite of the recent mental health crisis, insurance companies, including UnitedHealth Group, are doing what they can to limit coverage and deny claims for mental health related issues.[36]

A 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found a direct causal link between worker's wages and suicide rates, and that raising the minimum wage would result in a quick drop in the suicide rate.[16][37]

In August 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a survey conducted by the CDC found that 25.5 percent of people aged between 18 and 24 have seriously contemplated suicide within the last 30 days. For the age group 25 to 44, it was 16 percent. Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept said of the findings:[38]

In a remotely healthy society, one that provides basic emotional needs to its population, suicide and serious suicidal ideation are rare events. It is anathema to the most basic human instinct: the will to live. A society in which such a vast swath of the population is seriously considering it as an option is one which is anything but healthy, one which is plainly failing to provide its citizens the basic necessities for a fulfilling life.

Subgroups

Age and sex

The National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) keeps data on U.S. suicides.

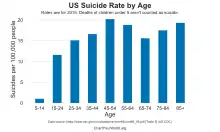

| Age (years) | 10 – 14 | 15 – 24 | 25 – 34 | 35 – 44 | 45 – 54 | 55 – 64 | 65 – 74 | 75+ | Unknown | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 265 | 4575 | 5887 | 5294 | 6198 | 5745 | 3463 | 3291 | 2 | 34727 |

| Females | 171 | 1148 | 1479 | 1736 | 2239 | 2014 | 940 | 510 | 1 | 10238 |

| Male/Female Ratio | 1.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 3.4 |

| Total | 436 | 5723 | 7366 | 7030 | 8437 | 7759 | 4403 | 3801 | 3 | 44965 |

Based on the NVDRS 2016 data, the New York Times acknowledged that, among men, those over 65—who make up a smaller proportion of the population—are at greatest risk of death by suicide.[40] The NVDRS 2015 data showed that, among men of all races, men over 65 were the most likely to die of suicides (27.67 suicides per 100,000), closely followed by men 40–64 (27.10 suicides per 100,000). Men 20–39 (23.41 per 100,000) and 15–19 (13.81 per 100,000) were less likely to die of suicides.[41]

White men are more likely to commit suicide. White men account for nearly 70% of suicides in the United States.[42]

Race

Native Americans and White Americans have the highest suicide rate in the United States.[43][44]

By state

There are significant variations in the suicide rates of the different states.[27] A number of theories for these differences have been suggested, ranging from socioeconomics (rural poverty) to access to firearms and social isolation (low population densities),[45] and a study in 2011 found a correlation between altitude above sea level and suicide.[46]

| Rank | State | Suicide rate per 100,000 people |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wyoming | 29.3 |

| 2 | Alaska | 28.5 |

| 3 | Montana | 26.2 |

| 4 | New Mexico | 24 |

| 5 | Colorado | 22.1 |

| 6 | Utah | 21.2 |

| 7 | South Dakota | 20.9 |

| 8 | Oklahoma | 20.5 |

| 9 | Oregon | 20.4 |

| 10 | Idaho | 20.4 |

| 11 | Nevada | 19.8 |

| 12 | Maine | 19.4 |

| 13 | Arizona | 18.7 |

| 14 | West Virginia | 18.5 |

| 15 | Missouri | 18.2 |

| 16 | Kansas | 18.2 |

| 17 | North Dakota | 18.1 |

| 18 | Arkansas | 18 |

| 19 | New Hampshire | 17.5 |

| 20 | Tennessee | 17.2 |

| 21 | Iowa | 16.7 |

| 22 | Kentucky | 16.5 |

| 23 | Alabama | 16.3 |

| 24 | South Carolina | 16.2 |

| 25 | Nebraska | 16.1 |

| 26 | Vermont | 16 |

| 27 | Washington | 15.9 |

| 28 | Hawaii | 15.5 |

| 29 | Ohio | 15.1 |

| 30 | Louisiana | 15 |

| 31 | Georgia | 14.6 |

| 32 | Florida | 14.5 |

| 33 | Mississippi | 14.4 |

| 34 | Minnesota | 14.4 |

| 35 | Michigan | 14.3 |

| 36 | Indiana | 14.2 |

| 37 | Pennsylvania | 14.1 |

| 38 | Wisconsin | 14 |

| 39 | Texas | 13.4 |

| 40 | Virginia | 12.8 |

| 41 | North Carolina | 12.5 |

| 42 | Connecticut | 11.4 |

| 43 | Delaware | 11.3 |

| 44 | Illinois | 10.9 |

| 45 | Rhode Island | 10.7 |

| 46 | California | 10.7 |

| 47 | Maryland | 10.3 |

| 48 | Massachusetts | 8.7 |

| 49 | New York | 8.3 |

| 50 | New Jersey | 8 |

College students

For college students, suicide is the second highest cause of death.[48] The risk tends to be underestimated, as many falsely believe that young people do not have thoughts about suicide.[49] The suicide rate for male students is about three times higher than that of female students.[50] The study of suicide rates and trends was not common in the past, but it has gained more attention in 2019. From 1990 to 2004, about 1,404 college students died by suicide. This is about 6.5 percent of those who died by suicide nationwide. In 2014, the adjusted age rate was higher for male than female: the suicide rate for males was 20.7 per 100,000 while the rate for females was 5.8 per 100,000.[50]

While counseling services can help prevent suicide, resource availability may be insufficient.[48] Students who do not go to counseling services are at 18 times more at risk of suicide compared to those who do. If a college student has any suicidal thoughts, it is always critical to let others, such as members of the school, family, or friends know.[50]

Occupation

A 2009 U.S. Army report indicates military veterans have double the suicide rate of non-veterans, and more active-duty soldiers have died from suicide than in combat in the Iraq War (2003–2011) and War in Afghanistan (2001–2021).[51] Colonel Carl Castro, director of military operational medical research for the Army noted "there needs to be a cultural shift in the military to get people to focus more on mental health and fitness."[52] In 2012, the US Army reported 185 suicides among active-duty troops, exceeding the number of combat deaths in that year (176). This figure has significantly increased since 2001, when the number of suicides was 52.[53]

According to a June 2021 study published by Brown University's Cost of War Project, deaths from suicide among active U.S. military personnel and veterans of the post-9/11 conflicts outnumber combat deaths for those same conflicts by four times, with the numbers being 30,177 and 7,057 respectively.[54]

Suicide rates among veterinarians are a growing problem: suicide rates among male veterinarians are twice the national average, and among female veterinarians the suicide rate is 3.5 times the national average.[55]

LGBTQ

Attempted suicide rates for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and adults in the U.S. are elevated in comparison to national rates.[56]

Health or Disability

Patients with chronic pain are twice as likely to attempt suicide compared with those without chronic pain.[57]

Studies have found very high rates of suicide in people with autism spectrum disorders, including high functioning autism and what was formerly known as Asperger syndrome. Autism and particularly Asperger syndrome are highly associated with clinical depression and as many as 30 percent or more of people with Asperger syndrome also suffer from depression.[58]

Those with ADHD are 3-5 times more likely to die by suicide. A comorbidity of depression with ADHD is the best predictor of suicidal thoughts in adolescence.[59][60]

Murder–suicide

There have been many high-profile incidents in the United States in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s of individuals thought to be attempting "suicide by cop" or killing others before killing themselves. Examples include the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, the 2010 Austin plane crash, the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the 2014 Isla Vista killings, and the 2017 Las Vegas shooting.

Comparison between countries

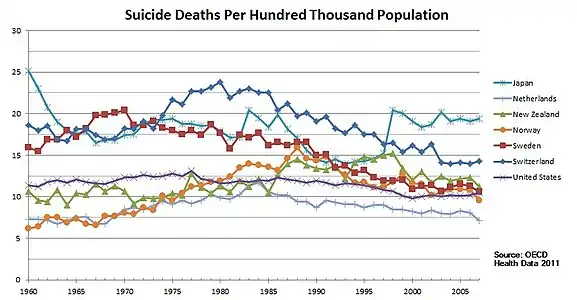

Trend of suicide deaths from 1960 to 2007 for Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States

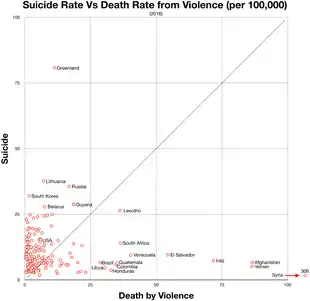

Trend of suicide deaths from 1960 to 2007 for Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States Suicide vs violent deaths 2016

Suicide vs violent deaths 2016

See also

- Assisted suicide in the United States

- Euthanasia in the United States

- National Suicide Prevention Week

- Suicide among LGBT youth

- Suicide among Native Americans in the United States

- Suicide in colleges in the United States

- Teenage suicide in the United States

References

- "WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports". Webappa.cdc.gov. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "New International Report on Health Care: U.S. Suicide Rate Highest Among Wealthy Nations | Commonwealth Fund". www.commonwealthfund.org. January 30, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "NCHS Data Brief, Number 433, March 2022" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- "Products – Data Briefs – Number 241 – April 2016". Cdc.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- "Data Brief 241: Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014 : Data table for Figure 1. Age-adjusted suicide rates, by sex: United States, 1999–2014" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- "Deaths: Final Data for 2014" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Garnett, Matthew; Curtin, Sally; Stone, Deborah (March 2, 2022). "Products - Data Briefs - Number 431 - January 2022". www.cdc.gov. doi:10.15620/cdc:114217. S2CID 246722506. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- Tavernise, Sabrina (April 22, 2016). "U.S. Suicide Rate Surges to a 30-Year High". The New York Times.

- TARA PARKER-POPE (May 2013). "Suicide Rates Rise Sharply in U.S." The New York Times.

- "Suicide Statistics — AFSP". AFSP. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "U.S. suicide rate surges to three decade high". Chicago Tribune. Tronc. April 22, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- Tavernise, Sabrina (April 22, 2016). "U.S. Suicide Rate Surges to a 30-Year High". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- Maggie, Fox (June 7, 2018). "Suicide rates are up 30 percent since 1999, CDC says". NBC News. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- Hedegaard, Holly; Curtin, Sally C.; Warner, Margaret (June 2018). Suicide Rates in the United States Continue to Increase (PDF). NCHS Data Brief No. 309 (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Kight, Stef W. (March 6, 2019). "Deaths by suicide, drugs and alcohol reached an all-time high last year". Axios. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Cerullo, Megan (April 30, 2019). "Want to decrease suicide? Raise the minimum wage, researchers suggest". CBS News. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Koons, Cynthia (June 20, 2019). "Latest Suicide Data Show the Depth of U.S. Mental Health Crisis". Bloomberg. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- Ducharme, Jamie (June 13, 2019). "More Millennials Are Dying 'Deaths of Despair,' as Overdose and Suicide Rates Climb". TIME. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- "Facts at a Glance 2015" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Suicide". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- "U.S. Suicide Rate Increases". Jhsph.edu. September 3, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "Suicide Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration". Mentalhealth.samhsa.gov. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "Substance Abuse and Mental Health Publications| SAMHSA Store". Mentalhealth.samhsa.gov. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- "In Harm's Way: Suicide in America – MHM: Suicide". Mental-health-matters.com. February 17, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- Engelhardt, H. Tristram Jr.; Malloy, Michele (1982–1983), "Suicide and Assisting Suicide: A Critique of Legal Sanctions", Southwestern Law Journal, Sw. L.J., 36 (4): 1003–37, PMID 11658640

- DS Hamermesh; NM Soss (1974), "An economic theory of suicide", The Journal of Political Economy, 82 (1): 83–98, doi:10.1086/260171, JSTOR 1830901, S2CID 154390756

- "2015 Annual Report". America's Health Rankings. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- "FastStats". Cdc.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Administration (SAMHSA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (July 15, 2022). "U.S. Transition to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline Begins Saturday". HHS.gov. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- Curtin, Sally C.; Warner, Margaret; Hedegaard, Holly (April 2016). "Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief No. 214" (PDF). NCHS Data Brief. 241 – via CDC.

- Olfson, Blanco, Wall, Mark, Carlos, Melanie (November 1, 2017). "National Trends in Suicide Attempts Among Adults in the United States". JAMA Psychiatry. 74 (11): 1095–1103. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2582. PMC 5710225. PMID 28903161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - US Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Surgeon General; National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (September 2012). "2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action". US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Knox, Kelly (2015). "If Suicide Is a Public Health Problem, What Are We Doing to Prevent It?". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (1): 37–45. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.1.37. PMC 1449822. PMID 14713694.

- "Applying Science. Advancing Practice" (PDF).

- "Home". suicidepreventionlifeline.org. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- Koons, Cynthia; Tozzi, John (May 16, 2019). "As Suicides Rise, Insurers Find Ways to Deny Mental Health Coverage". Bloomberg. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- William H. Dow; Anna Godøy; Christopher A. Lowenstein; Michael Reich (April 2019). "Can Economic Policies Reduce Deaths of Despair?". doi:10.3386/w25787.

- Greenwald, Glenn (August 28, 2020). "The Social Fabric of the U.S. Is Fraying Severely, if Not Unravelling". The Intercept. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- 2016, United States: Suicide Injury Deaths and Rates per 100,000. (All Races, Both Sexes, All Ages)". Retrieved March 3, 2018 – via WISQARS Fatal Injury Reports – CDC.

- Span, Paula (May 25, 2018). "In Elderly Hands, Firearms Can Be Even Deadlier Image". New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- "National Violent Death Reporting System". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- "Men and Suicide: Why are white men most at risk?". Baton Rouge General.

- "3. Suicide, Race, and Ethnicity | ATrain Education".

- Strickland, C. June (1996). "Suicide Among American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Canadian Aboriginal Youth: Advancing the Research Agenda". International Journal of Mental Health. 25 (4): 11–32. doi:10.1080/00207411.1996.11449375. JSTOR 41344797.

- Thompson, J. (January 14, 2015). "Is altitude causing suicide in the West?". High Country News. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- Barry Brenner; David Cheng; Sunday Clark (2011), "Positive Association between Altitude and Suicide in 2584 U.S. Counties", High Alt. Med. Biol., High Altitude Medicine and Biology, 12 (1): 31–5, doi:10.1089/ham.2010.1058, PMC 3114154, PMID 21214344

- "Stats of the State - Suicide Mortality". CDC National Center for Health Statistics. January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- Schwartz, Allan (2006). "College Students Suicide in the United States: 1990-1991 Through 2003-2004". Journal of American Health. 54 (6): 341–352. doi:10.3200/jach.54.6.341-352. PMID 16789650. S2CID 37259134.

- "Youth". suicidepreventionlifeline.org. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "Welcome to CDC stacks | Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014 - 39008 | Stephen B. Thacker CDC Library collection". stacks.cdc.gov. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Woods, Tyler (September 7, 2009). "This Week Is National Suicide Prevention Week". Emax Health. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- Jelinek, Pauline (September 5, 2008). "Army: soldier suicide rate may set record again". USA Today/Associated Press. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- Wood, David (September 25, 2013). "Army Chief Ray Odierno Warns Military Suicides 'Not Going To End' After War Is Over". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- Hernandez, Joe (June 24, 2021). "Since 9/11, Military Suicides Are 4 Times Higher Than Deaths In War Operations". NPR. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- Leffler, David (January 23, 2019). "Suicides Among Veterinarians has become a Growing Problem". Washington Post. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- Haas, Ann P.; Eliason, Mickey; Mays, Vickie M.; Mathy, Robin M.; Cochran, Susan D.; D'Augelli, Anthony R.; Silverman, Morton M.; Fisher, Prudence W.; Hughes, Tonda; Rosario, Margaret; Russell, Stephen T. (December 30, 2010). "Suicide and Suicide Risk in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations: Review and Recommendations". Journal of Homosexuality. 58 (1): 10–51. doi:10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. ISSN 0091-8369. PMC 3662085. PMID 21213174.

- "Patients With Chronic Pain Are Twice as Likely to Attempt Suicide". Clinical Pain Advisor. October 4, 2017.

- Johnny L. Matson; Marie S. Nebel-Schwalm. "Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: An overview" (PDF). Vcuautismcenter.org. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Barkley, Russell A. (October 7, 2019). "The Adverse Health Outcomes, Economic Burden, and Public Health Implications of Unmanaged Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)" (PDF). russellbarkley.org.

- Barbaresi, William J.; Colligan, Robert C.; Weaver, Amy L.; Voigt, Robert G.; Killian, Jill M.; Katusic, Slavica K. (April 1, 2013). "Mortality, ADHD, and Psychosocial Adversity in Adults With Childhood ADHD: A Prospective Study". Pediatrics. 131 (4): 637–644. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2354. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 3821174. PMID 23460687.