Urbach–Wiethe disease

Urbach–Wiethe disease is a very rare recessive genetic disorder, with approximately 400 reported cases since its discovery.[1][2][3] It was first officially reported in 1929 by Erich Urbach and Camillo Wiethe,[4][5] although cases may be recognized dating back as early as 1908.[6][7][8]

| Urbach-Wiethe disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Lipoid proteinosis and Hyalinosis cutis et mucosae |

| |

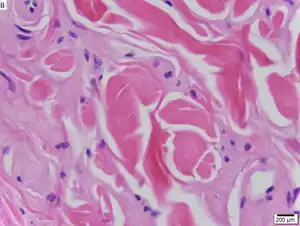

| Urbach–Wiethe disease in skin biopsy with H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

The symptoms of the disease vary greatly from individual to individual. They may include a hoarse voice, lesions and scarring on the skin, easily damaged skin with poor wound healing, dry, wrinkly skin, and beading of the papules around the eyelids.[6][9][10] All of these are results of a general thickening of the skin and mucous membranes. In some cases there is also a hardening of brain tissue in the medial temporal lobes, which can lead to epilepsy and neuropsychiatric abnormalities.[11] The disease is typically not life-threatening and patients do not show a decreased life span.[10]

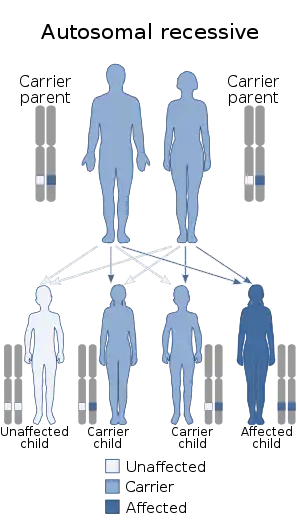

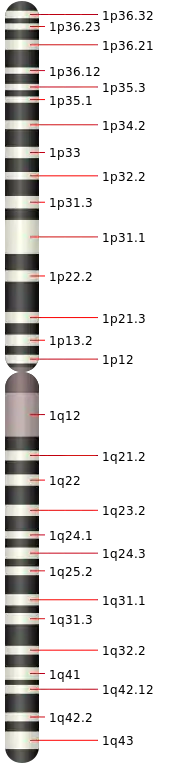

Because Urbach–Wiethe disease is an autosomal recessive condition individuals can be carriers of the disease but show no symptoms. The disease is caused by loss-of-function mutations to chromosome 1 at 1q21, the extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) gene.[12] The dermatological symptoms are caused by a buildup of a hyaline material in the dermis and the thickening of the basement membranes in the skin.[9] Urbach–Wiethe disease is typically diagnosed by its clinical dermatological manifestations, particularly the beaded papules on the eyelids. The discovery of the mutations within the ECM1 gene has allowed the use of genetic testing to confirm an initial clinical diagnosis. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and immunohistochemical staining may also be used for diagnosis.[6][13]

Currently, there is no cure for Urbach–Wiethe disease although there are ways to individually treat many of its symptoms.[2] The discovery of the mutations of the ECM1 gene has opened the possibility of gene therapy or a recombinant ECM1 protein for Urbach–Wiethe disease treatment, but neither of these options are currently available. Some researchers are examining patients with Urbach–Wiethe disease to learn more about other conditions that exhibit similar neurological symptoms, such as autism.

Symptoms and signs

Urbach–Wiethe disease is characterized by both neurological and dermatological symptoms.[14][15]

Dermatological

Although symptoms can vary greatly between affected individuals, even those within the same family, symptoms normally begin in infancy and are typically a result of thickening skin and mucous membranes.[2] The first symptom is often a weak cry or a hoarse voice due to a thickening of the vocal cords. The hoarse voice can be one of the most striking clinical manifestations of the disease.[9] Lesions and scars also appear on the skin, usually the face and the distal parts of the limbs.[6] This is often the result of poor wound healing and the scarring continues to increase as the patient ages, leaving the skin with a waxy appearance. Skin may be easily damaged as a result of only a minor trauma or injury, leaving many blisters and additional scars.[10] The skin is also usually very dry and wrinkly. White or yellow infiltrates form on the lips, buccal mucosa, tonsils, uvula, epiglottis and frenulum of the tongue.[6] This can lead to upper respiratory tract infection and sometimes requires tracheostomy to relieve the symptom.[9] Too much thickening of the frenulum can restrict tongue movement and may result in speech impediments.[16] Beading of the papules around the eyelids is a very common symptom and is often used as part of a diagnosis of the disease. Some other dermatological symptoms that are sometimes seen but less common include hair loss, parotitis and other dental abnormalities, corneal ulceration, and focal degeneration of the macula.[17]

Neurological

Although the dermatological changes are the most obvious symptoms of Urbach–Wiethe disease, many patients also have neurological symptoms. About 50–75% of the diagnosed cases of Urbach–Wiethe disease also show bilateral symmetrical calcifications on the medial temporal lobes.[18] These calcifications often affect the amygdala and the periamygdaloid gyri.[11] The amygdala is thought to be involved in processing biologically relevant stimuli and in emotional long-term memory, particularly those associated with fear, and both PET and MRI scans have shown a correlation between amygdala activation and episodic memory for strongly emotional stimuli.[14] Therefore, Urbach–Wiethe disease patients with calcifications and lesions in these regions may suffer impairments in these systems. These calcifications are the result of a buildup of calcium deposits in the blood vessels within this brain region. Over time, these vessels harden and the tissue they are a part of dies, causing lesions. The amount of calcification is often related to disease duration.[10] The true prevalence of these calcifications is difficult to accurately state as not all patients undergo brain imaging. Some patients also exhibit epilepsy and neuropsychiatric abnormalities. Epilepsy symptoms could begin with light anxiety attacks and can be controlled with anti-epileptic medications.[10] Other patients present with symptoms similar to schizophrenia while some suffer from mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders.[16][19]

Causes

Researchers have mapped Urbach–Wiethe disease to chromosome 1 at 1q21 and specifically identified the extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1) gene as the gene containing mutations that can lead to the development of the condition.[12] At this point, 41 different mutations within ECM1 have been reported to lead to Urbach–Wiethe disease.[13] These were all homozygous loss-of-function mutations (i.e. nonsense, frameshift or internal deletions).[9] It is an autosomal recessive condition,[2][13] requiring two mutated copies of the ECM1 gene to cause the disease.[20]

ECM1 codes for a glycoprotein of previously unknown origin. The discovery that the loss of ECM1 expression leads to the symptoms associated with Urbach–Wiethe disease suggests that ECM1 may contribute to skin adhesion, epidermal differentiation, and wound healing and scarring.[12] It is also thought to play a role in endochondral bone formation, tumor biology, endothelial cell proliferation and blood vessel formation.[9]

The dermatological symptoms are caused by a buildup of a hyaline material in the dermis and the thickening of the basement membranes in the skin.[9] The nature of this material is unknown, but researchers have suggested that it may be a glycoprotein, a glycolipid, an acid mucopolysaccharide, altered collagen or elastic tissue.[6]

Diagnosis

Urbach–Wiethe disease is typically diagnosed by its clinical dermatological manifestations, particularly the beaded papules on the eyelids. Doctors can also test the hyaline material with a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, as the material colors strongly for this stain.[6]

Immunohistochemical skin labeling for antibodies for the ECM1 protein as labeling has been shown to be reduced in the skin of those affected by Urbach–Wiethe disease.[13] Staining with anti-type IV collagen antibodies or anti-type VII collagen antibodies reveals bright, thick bands at the dermoepidermal junction.[9]

Non-contrast CT scans can image calcifications, but this is not typically used as a means of diagnosing the disease. This is partly due to the fact that not all Urbach-Wiethe patients exhibit calcifications, but also because similar lesions can be formed from other diseases such as herpes simplex and encephalitis. The discovery of mutations within the ECM1 gene has allowed the use of genetic testing to confirm initial clinical diagnoses of Urbach–Wiethe disease. It also allows doctors to better distinguish between Urbach–Wiethe disease and other similar diseases not caused by mutations in ECM1.

Treatment

Currently, there is no cure for Urbach–Wiethe disease although there are some ways to individually treat many of its symptoms. There has been some success with oral dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and intralesional heparin, but this is not true in all cases.[9][19] D-penicillamine has also shown promise, but has yet to have been used extensively.[13] There are also some reports of patients being treated with etretinate, a drug typically prescribed to treat psoriasis.[17] In some cases, calcifications in the brain can lead to abnormal electrical activity among neurons. Some patients are given anti-seizure medication to help deal with these abnormalities. Tracheostomy is often used to relieve upper respiratory tract infections. Carbon dioxide laser surgery of thickened vocal cords and beaded eyelid papules have improved these symptoms for patients.[9] The discovery of the mutations of the ECM1 gene has opened the possibility of gene therapy or a recombinant EMC1 protein for Urbach–Wiethe disease treatment, but neither of these two options are currently available.

Prognosis

Urbach–Wiethe disease is typically not a life-threatening condition.[2] The life expectancy of these patients is normal as long as the potential side effects of thickening mucosa, such as respiratory obstruction, are properly addressed.[10] Although this may require a tracheostomy or carbon dioxide laser surgery, such steps can help ensure that individuals with Urbach–Wiethe disease are able to live a full life. Oral dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) has been shown to reduce skin lesions, helping to minimize discomfort for these individuals.[9]

Incidence

Urbach–Wiethe disease is very rare; there are fewer than 300 reported cases in medical literature.[2] Although Urbach–Wiethe disease can be found worldwide, almost a quarter of reported diagnoses are in South Africa.[2] Many of these are in patients of Dutch, German, and Khoisan ancestry.[2][12] This high frequency is thought to be due to the founder effect.[13] Due to its recessive genetic cause and the ability to be a carrier of the disease without symptoms, Urbach–Wiethe disease often runs in families. In some regions of South Africa, up to one in 12 individuals may be carriers of the disease.[9] Most of the case studies involving Urbach–Wiethe disease patients involve only one to three cases and these cases are often in the same family. Due to its low incidence, it is difficult to find a large enough number of cases to adequately study the disease.

History

In 1908, what appears to be the first case of Urbach–Wiethe disease was reported by Friedrich Siebenmann, a professor of otolaryngology in Basel, Switzerland. In 1925, Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss dermatologist, reported on three similar patients.[6] An official report of Urbach–Wiethe disease was first described in 1929 by a Viennese dermatologist and otorhinolaryngologist, Urbach and Wiethe.[12] Its original name of 'lipoidosis cutis et mucosae' was changed to 'lipoid proteinosis cutis et mucosae' due to Urbach's belief that the condition was due to abnormal lipid and protein deposits within the tissues.[12] Some have debated as to whether or not the disease is actually a form of mucopolysaccharidosis, amyloidosis, or even porphyria. The discovery of the Urbach–Wiethe disease causing mutation to the ECM1 gene has now provided a definitive way to differentiate Urbach–Wiethe disease from these other conditions.[9]

See also

References

- "Meet the woman who can't feel fear - The Washington Post".

- DiGiandomenico S.; Masi R.; Cassandrini D.; El-Hachem M.; DeVito R.; Bruno C.; Santorelli F.M. (2006). "Lipoid proteinosis: case report and review of the literature". Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 26 (3): 162–7. PMC 2639960. PMID 17063986.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- synd/924 at Who Named It?

- Urbach E, Wiethe C (1929). "Lipoidosis cutis et mucosae". Virchows Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin. 273 (2): 285–319. doi:10.1007/bf02158983. S2CID 42016927.

- Caro I (1978). "Lipoid proteinosis". International Journal of Dermatology. 17 (5): 388–93. doi:10.1111/ijd.1978.17.5.388. PMID 77850. S2CID 43544386.

- Lever, Walter F.; Elder, David A. (2005). Lever's histopathology of the skin. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-7817-3742-5.

- Siebenmann F. (1908). "Über Mitbeteilingung der Schleimhaut bei allgemeiner Hyperkeratose der Haut". Arch Laryngol. 20: 101–109.

- Hamada, T. (2002). "Lipoid proteinosis". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 27 (8): 624–629. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01143.x. PMID 12472532. S2CID 28344373.

- Appenzeller, S; Chaloult, E; Velho, P; De Souza, E. M.; Araújo, V. Z.; Cendes, F; Li, L. M. (2006). "Amygdalae Calcifications Associated with Disease Duration in Lipoid Proteinosis". Journal of Neuroimaging. 16 (2): 154–156. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00018.x. PMID 16629738. S2CID 30567332.

- Staut, C. C. V.; Naidich, T. P. (1998). "Urbach-Wiethe Disease(Lipoid Proteinosis)". Pediatric Neurosurgery. 28 (4): 212–214. doi:10.1159/000028653. PMID 9732251. S2CID 46862405.

- Hamada T.; McLean WHI; Ramsay M.; Ashton GHS; Nanda A.; et al. (2002). "Lipoid proteinosis maps to 1q21 and is caused by mutations in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene (ECM1)". Human Molecular Genetics. 11 (7): 833–40. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.7.833. PMID 11929856.

- Chan I.; Liu L.; Hamada T.; Sethuraman G.; McGrath J.A. (2007). "The molecular basis of lipoid proteinosis: mutations in extracellular matrix protein 1". Experimental Dermatology. 16 (11): 881–90. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00608.x. PMID 17927570.

- Siebert M.; Markowitsch H.J.; Bartel P. (2003). "Amygdala, affect and cognition: evidence from 10 patients with Urbach-Wiethe disease". Brain. 126 (12): 2627–37. doi:10.1093/brain/awg271. PMID 12937075.

- Mallory S.B.; Krafchick B.R.; Holme S.A.; Lenane P.; Krafchik B.R. (2005). "What syndrome is this? Urbach-Weithe syndrome (lipoid proteinosis)". Pediatric Dermatology. 22 (3): 266–7. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22321.x. PMID 15916581. S2CID 44925736.

- Thornton H.B.; Nel D.; Thornton D.; van Honk J.; Baker G.A.; Stein D.J. (2008). "The neuropsychiatry and neuropsychology of lipoid proteinosis". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 20 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1176/jnp.2008.20.1.86. PMID 18305289.

- Bahadir S.; Cobanoglu U.; Kapicioglu Z.; Kandil S.T.; Cimsit G.; et al. (2006). "Lipoid proteinosis: A case with ophthalmological and psychiatric findings". The Journal of Dermatology. 33 (3): 215–8. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00049.x. PMID 16620230. S2CID 34699559.

- Hurlemann R.; Wagner M.; Hawellek B.; Reich H.; Pieperhoff P.; Amunts K.; et al. (2007). "Amygdala control of emotion-induced forgetting and remembering: Evidence from Urbach-Wiethe disease". Neuropsychologia. 45 (5): 877–84. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.08.027. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-B8EF-3. PMID 17027866. S2CID 4101263.

- Cinaz P.; Guvenir T.; Gonlusen G. (1993). "Lipoid proteinosis: Urbach-Wiethe disease". Acta Paediatrica. 82 (11): 892–3. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12590.x. PMID 8241657. S2CID 31104438.

- Morovvati S, Farshadyeganeh P, Hamidizadeh M, Morovvati Z, Mohammadi SD (August 2018). "Mutation Analysis of ECM1 Gene in Two Related Iranian Patients Affected by Lipoid Proteinosis". Acta Medica Iranica. 56 (7): 474–477. Retrieved 1 September 2020.